Your ancestors for several generations were Old Believers. What caused you to reconsider the faith of your fathers and join the “new ritualists”?

I was raised a diligent Old-Believer. Even though my parents, as well as my brothers and sister were born and raised in America, nevertheless, my upbringing in the Old Rite of The Russian Church was quite diligent. I suppose fortunately for me, I attended a three-year summer seminary taught by our nastavnik (spiritual mentor-A.P.) who gave me and a couple other people a higher church education than most priestless Old-Believers have. We studied topics such as the World’s religions, the Bible, the History of the Russian Orthodox Church, History of the Christian Church, and so forth. During those studies, I became aware, as he taught us, that our position as priestless Old-Believers was really an irregularity, but an irregularity that was not caused by us, and probably not rectifiable. Thus, hopefully, it was something that God would understand. Yes, we can’t have the hierarchy and we can’t have Holy Communion, but God would understand our predicament. And perhaps it was even better that we didn’t partake of Holy Communion, because we weren’t worthy of having these sacraments any longer. I think this rationalization came about from the growth of a mentality of unworthiness in Russia that originated in the late middle ages. It seems evident to me that’s why infrequent Communion became so common in Russia as well.

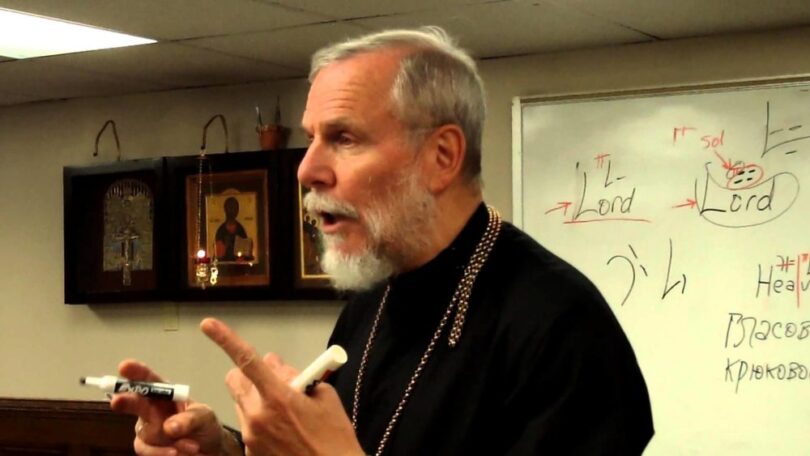

When I became an adult and I was an attorney, a lawyer, I was still very active in the Church. We had a crisis in our church where we had to ask the nastavnik to resign. Before that person became our parish nastavnik, we had a long-time nastavnik, who was my mentor. But he had retired and moved to Millville, New Jersey, where there was another priestless Old Believer community. But, as mentioned earlier, then we had a nastavnik who had personal problems, and the parish was literally dying. Our parishioners had been living in America for three generations, and most of them by now understood little about the Faith or the history of the Russian Church and its ramifications for us. Less and less parishioners were coming to services or parish activities and it came to a point where my wife and felt obligated that, for the parish’s sake, I had to leave the practice of law and become a nastavnik. When I became a full-time nastavnik, for the first time I had the opportunity to really start going through the church books. If you are a golovshchik (choir director- A.P.), as I was in our church – a person who starts the singing […], then you’re looking at the Festal Menaion, or the Octai and you’re only looking in Great Vespers, for how to sing the “Lord, I have Cried” stichera, and so forth. But now, as a nastavnik, I would look at the books and look at all the red instructions in the beginning. For the first time I would read about the Royal Doors, read about the priest putting on the vestments, the priest censing around the altar, about the blessing of loaves, and began to go “Oh!”, we’re really missing a great deal in our priestless services. As an Old-Believer I was always under the impression that we had retained everything of the Russian Orthodox Church, but the Nikonians had changed everything. Therefore if we didn’t have royal doors, and if we didn’t have the blessing of loaves, it was because these were Nikonian additions. For the first time I became aware that there were things that we’re really not doing, but the Nikonians are still doing these things.

Secondly, at the very time that I was engaged in this transition from lawyer to nastavnik, fortunately, there was a woman in Erie who belonged to the ROCOR church here. She lived upstairs from a member of our parish, and she began to tell me about a lot of new books that were coming out in English on Orthodoxy. I was not fluent in Russian as a child. No one in my generation was. My understanding of Slavonic was better than of modern Russian, but certainly not complete. So to read many of the Fathers was difficult because we didn’t have access to them, or we only had access to parts of their writings – and all in Church Slavonic. Because this woman advised us that we could procure many of these books at St. Tikhon’s, my wife and I went on a trip there after I left the practice of law, but before I was blessed to become a nastavnik. There I bought many books of the Fathers of the Church and, for the first time, I began reading such Holy Fathers as St. Polycarp, and other early Fathers who said that “where the bishop is, there is the Church and, where the bishop is not, there is not the Church”. This was the first time that I came to the idea that, “My goodness! Maybe our position really is not acceptable.” But still — this was 1976 when I became a nastavnik — still I certainly was not of a mentality of bringing about some sort of revolution in the parish by restoring priesthood. But now the seed had been planted in my mind — how do we become priested and what do we do? I was aware, shortly thereafter, of the lifting of the anathemas by the Church in Russia in 1971, and of the lifting of the anathemas against the Old Rite in 1974 by the Church Abroad. But the other nastavniki of the priestless Pomortsy parishes here in America, near Pittsburgh and in Detroit and New Jersey all took the position, “Well, this is really nice. The Nikonians finally realize they did wrong. We’ll thank them, but we’ll just go our merry way until we can bring all the Old-Believers together and have some kind of world Old-Believer conference.” This was a dream, a fantasy. When I realized, after a number of years, that this wasn’t going to happen, I started thinking to myself, “Well maybe we have to do things on our own. We can’t wait for everyone else to do something.”

I think another major aspect was when we started translating the services into English. I had no intention of translating the services into English. I knew all the paryers and common parts of the services in Slavonic. I knew most of these by heart. I didn’t need to do it in English. But I found that many of my parish families could neither understand anything in Slavonic nor read it. They said, “I know I should but I don’t. I’m not coming to services for hours when I understand nothing in the services.” So we began to determine that we had to start converting at least parts of the services into English. I began to translate, even with my limited abilities, and I found others with much more expertise in Slavonic to do the majority of that which was not already translated into English. I began to read homilies and patristic writings, all of these leading, of course, to the idea of the necessity of the Eucharist, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me and I in him, and so forth.”

So it was a process. It’s hard for me to name a day or time when it all seemed to become imperative that we restore priesthood to our parish – in spite of the rancor that it would cause in the parish. In 1979, I took a trip with Fr. Theodore Jurewicz, who was the rector of Our Lady’s Nativity ROCOR parish in Erie . We had both been friends after I became a nastavnik. In August, 1979, we made a visit to Jordanville for five or six days, almost to see if the leaders of the New Rite Church were really serious about the Old Ritualists . Would they really welcome us back into the Church? What did they feel? When I came back from that trip, there were two feelings I had. First of all, when we were there for our visit, and as I was awakened at 4:30 in the morning for Midnight Office and Liturgy, I became aware of the piety that obviously still existed in the “Nikonian” Church. I was also impressed by the rigidity of the fasting, and the simplicity of the meals, which were accompanied by the reading of the Lives of the Saints. Thus, I began to think, “Hmm. Here are these Nikonians, who are supposed to be so far off and so liberal and so modernist, I and I don’t know any places where we Old-Believers have services everyday and this kind of rigidity.” And when I sat down at the trapeza, I saw Vladyka Lavr eating. He ate there as if he were a simple monk at the head of the table. I came home after that visit thinking that these people where a lot more Orthodox than I was led to believe. I also left Jordanville feeling that some people are probably really sympathetic and really like us, and some people really don’t like us, and actually like nothing about the Old-Believers. So I came back with kind of a mixed feeling like, “Okay. We need to work toward this, but I’m still not sure where to go.”

In 1979, a series of significant events happened that played a major role in opening up the door to further action on this issue. All the other nastavniki in all the other Pomortsi parishes in America unexpectedly reposed in that year. This left a situation that, if I started on this process to the restoration of priesthood in our parish, I really wasn’t going to have to deal with the objections of these long-time nastavniki — that they knew the books, and what did I know as a mere 32 year old nastavnik? It would have been very difficult to convince my parishioners or anyone else that they were wrong and I was right. And, without a doubt, none of them would have shared my opinion that this was the right thing to do.

So I began more and more to go through this process. I don’t remember a date, I don’t remember a time, but in 1982 — we were getting Orthodox Life by this time — and I saw in Orthodox Life that there was a conference of the Church Abroad in Ipswich, near Boston. And I said to some of my parishioners, “I know we’re not in communion (I don’t know if I used that term with them), but we need to have more knowledge, we need to have more training, we need to have more interaction with other Orthodox people.” And, of course, I was leaning toward the idea that, even if we’re Old-Believers, we’re still Orthodox, and they’re still Orthodox. Let’s not have this idea that we’re completely isolated and can’t pray with them and so forth. So we decided to go to that conference in August of 1982. In the same year, I was contacted by an OCA businessman who used to come to Erie quite often. He had the head of the chaplains of the OCA invite me to an OCA clergy conference that took place at St. Vladimir’s Seminary every year in June, and I went to that clergy conference. It was during the Apostles’ Fast. Matins was advertised at 7:30 and breakfast at 8:00, and I thought “How do you do Matins in half an hour.” I was a little shocked to see how the services were really short-cut. They had cheese and dairy products during the Apostles’ Fast, which I didn’t understand, and even served cheese on Wednesday and Friday. After that conference, I came to the conclusion that we could not join the OCA because of these types of practices. But, it is important to note, that I really learned a great deal from that conference in the lectures of Frs. Schmemman, Meyendorff and Hopko, and I did not leave with the mentality that these were modernist, polluted OCA Orthodox. I really left with the mentality that in the OCA there is a dedicated level of Orthodox Christianity, and even though the OCA this may not be a place where we could really be comfortable, still, we really needed to come into some sort of more connection and contact with the other Orthodox.

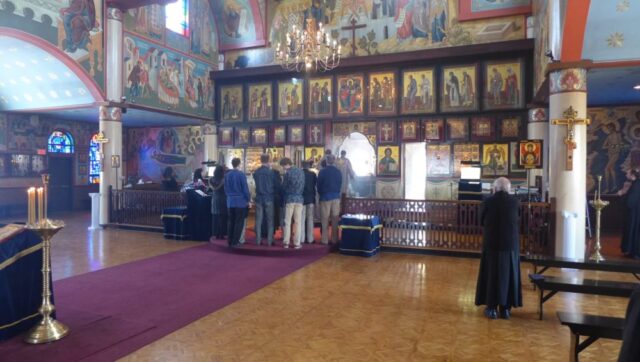

When we came to Ipswich and the ROCOR conference in August of 1982, it was a completely different experience. We arrived there in the afternoon of August 1st (new calendar date) a little before the vigil for the Prophet Elijah. Ipswich was very closely connected to the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, so the monks were there to aid in the services, and they served the Vigil in an extremely long fashion. They sang the “First Kathisma” verse by verse and, as a matter of fact (I had two children there, with my son at the time being only a 6 nonth old baby), and we thought “How long can a New Rite Vigil take?” The way they served it, the Vespers portion itself took about two and a half hours. With our tail between our legs, we left after Vespers. We Old-Believers thought it was way too long for our little baby. Also we were greatly relieved to find that on Wednesday and Friday, they were very diligent in following the Orthodox fasting rules. During the conference, Vespers and Liturgy were served every day.

During that week I was extremely moved. One day during the Liturgy I stood there and remembered all of my grandparents and my forefathers who had never in their entire life partaken of the Eucharist. Watching people take Communion, I stood there and cried, and thought about the fact that in their entire lives my forebers had never experienced this. The next morning I went to Liturgy, and I thought about all the children in my parish who were not taking Communion and were not partaking of a full sacramental life. I vowed at that time that I could never allow another generation to go by without partaking of the Sacraments. So I began to try to find the best way possible for us to restore the priesthood to our community.

I had looked to see about the Old Believer Byelokrinitsa hierarchy. There were three impediments here. First of all, they do not recognize any other Churches except their own Old Believer hierarchy. Secondly, this hierarachy had an irregular origin. It began with a single bishop who then consecrated other bishops. Finally, it was, of course, controlled by the Soviet state at that time. A second consideration was the Moscow Patriarchate, which was also under the control of the Soviet state. Also there were practices in the Moscow Patriarchate, at least at that time, which I felt were too sloppy (such as the willingness to allow non-immersion baptism). And so, really the only logical choice was the Church Abroad. So I came back from that conference in August of 1982 and I organized a study committee. I took a prominent member from each of the patriarchal families of our parish and ended up with a commitee of about fifty people to begin studying this process of whether or not it was possible to bring back priesthood. I called the committee the “Committee to study the possibility of the restoration of the priesthood.” By this time, already a number of our parishioners were up in arms, saying that I was already too close with the Nikonians, and we had introduced English, and so on. They were really unhappy with what I was doing and they were already in the mentality of deposing me or convincing me to resign as nastavnik of the parish. Neither option succeeded for them, and we went through the proposed study process. I presented the members of the committee the historical and developmental background of the Russian Church, as well, of course, as the Scriptural and patristic writings that were germane to this issue. At the end of December of 1982, we finished the study committee. The committee voted on whether or not we would bring to our parishioners a recommendation to restore priesthood. The vote was something like forty-two to seven in favor of recommending the restoration of priesthood by means of a union with the Russian Church Abroad. We brought it before our parish and, on the ninth of January (new calendar date) we had a parish vote on that recommendation. By that time, about a quarter of my parish had broken off from us. They were still voting, but they were holding services in another place. They had actually presented me with petitions saying that I needed to resign, that everything I was doing was contrary to the Old-Believers, that I was a traitor to the Old-Believers, and so forth. It was a very difficult time. I told my wife that I truly believed that one of them would kill me. I’m not trying to be dramatic; I really believed that. I told her that if that happened she should try to forgive them and understand that they really didn’t comprehend what this was all about. I had some experiences where people threatened us. Someone from the other group spit at my wife. I had a parishioner who met me in a hospital elevator filled with non-Orthodox people who began screaming at me that I was damned to hell and so forth. At any rate, that’s how the decision to restore priesthood was made..

We met with Bishop Gregory Grabbe in late January 1982 to try to negotiate a path for us to come into the Church Abroad. I would like to say this: it was at the conference at Ipswich that Archbishop Vitaly (Bishop Gregory Grabbe was there too, but it was Archbishop Vitaly, who was not Metropolitan yet) who was extremely kind to us, welcoming me, telling me “We’d like to have you come to our Church. You need to write to the Bishops and tell them your thoughts and what you’d like to do. Do that before our next Synod meeting and I will do everything I can to help the process to bring your parish into the Church Abroad.” So, I was very grateful to him. I think he was very responsible in helping us come to priesthood.

Could you explain to us how the reality of the New World influenced your decision to join the “new ritualist” Church?

That’s a really good question. There were many reasons. The most primary one was, of course, that I realized we were living without the full sacramental life of the Church. Priestless Old-Believers don’t always understand that. They think this is the way that it’s always been and things are fine. That was certainly reason number one. The other one however was, because we lived in America where there were only four groups of priestless Old-Believers. The other three were in positions where it was evident that they were not doing very well and their long term survival was questionable. There was a new group of Old-Believers that had settled in Oregon ion the 1060’s, but they had taken the mentality that, “No one else can pray with us, we won’t even pray with each other, we won’t pray with you. We’ll have nothing to do with you. We’re in a separate place.” This wasn’t a viable option for us. And, even if it was, the reality was, as we were now in the third generation of American born people, with our parishioners receiving higher education, many of them were leaving Erie looking for employment consistent with the skills they had acquired through their higher education. Many of them were looking to relocate in places like Chicago, Boston, Washington. What had happened with Old-Believers in the past who moved away from one of the bosom churches in Erie, Marianna, or Detroit, is that, once they went off, the first generation actually did follow the Orthodox, Old-Rite faith — but by the second generation the preservation of the faith was rapidly dissipating. And I was already in the process where I would go to these places where there were these groups of Old-Believers, in Boston, New York, eastern Pennsylvania. I would go to them and confess them and find out that it was almost a joke. They weren’t following the Faith anymore; what kind of Orthodox people are they? The same thing was true with us, where I would often think, “We’ve got to have a situation where we can say to people, ‘Yes, you come from an Old-Rite background, but you’re an Orthodox Christian and, if you can’t find a place to be an Old-Believer, you need to to look for another Orthodox Church. You’ve got to go to a church.'” This is what I was telling these other groups when I would go to them. “Why are you having me come here once a year? You have an Orthodox Church here. You have one in New York.” The answer was, “They’re not like us!” So part of the effect of living in the New World, especially as second and third-generation people was that we had to be able to have a place where we could have our people go and be able to participate and stay in the Faith, or else they will end up being nothing, which is most likely, or they will end up being Catholics and Protestants. But, more likely they won’t, because their parents will say “That’s not what I want you to do and, as long as you wear your cross, that’s still okay with me, you’ll still be an Old-Believer.” So that had a huge effect. If I had been in a place in which there were many priestless Old-Believer communities, like in Latvia, it may have been a different story. But in this country we were in such an insignificant minority that I recognized that we had to be able to somehow align ourselves with other Orthodox, where you’d say, “Okay, maybe it’s not an Old-Rite Church, but at least it’s Orthodox.” One last stumbling block remained-I had to be convinced that I really found that the New Rite was not heretical, because that was one of the criticisms and objections made to this process.

But can you say that education and the need to translate things into English also played its role, because you were forced to answer questions: How would you translate “Isus” (older Russian way of denoting the name “Jesus”)?

Well there’s two aspects to that. That’s a good point, Father, because, once you translate into English, then a lot of the issues that were the whole cause of the schism disappear: the whole question of “Isus” or “Iisus,” “Veki Vekom, Amin” or “Veki Vekov, Amin” (“now and ever and unto the ages of ages” – A.P.) — they disappear in English. A lot of them disappear.

What does “Old rite” mean for your congregation? Why is it important for you to preserve it?

That’s a very interesting question, and I suppose there is some debate as to whether that ought to remain a long term goal. There is some debate because, of course, I have tried so hard to convince people that they need to understand the most important things. There are three levels. First of all, most important of all, we’re Christians. Secondly, we’re Orthodox Christians. Thirdly, we’re Old Ritualists. That certainly ought to be the last concern. I think I’ve succeeded enough in that now there are people who say, “Well? Why is it so important to maintain the Old Rite?” And if they were not Old Rite in the future, I wouldn’t consider it a tragedy. Our beloved late Vladyka Daniel once mentioned to people that he came to understand that no one understood any Slavonic here now, and so when we translated into English, that was the first time that people began to understand here, even the homily readings that spoke to the need for Holy Communion. We have homily readings right before Christmas that mention partaking of the Eucharist, so that had a big effect. Vladika Daniel believed that the understanding of such things as these led us to a correct decision to unite with the “Nikonians’, but he also believed that we had an obligation to our forebears to preserve what they had given us. He also believed it was important for the entire Church that there continued to be a role parish that provided the Old Rite.

So I think it’s important because I think the Old Rite really does represent something really historical and really precious as a part of the Orthodox Church. I tell people all the time, “I would never tell you that the Old Rite is the only way to do things. I would never tell you that there aren’t evolutionary processes in the Church. But what I would tell you is that if you really want to know ancient practices of the Russian Church — maybe not as far back as the 900’s, but certainly as early as the 1200’s and 1300’s, then the Old Rite is really doing that. And sometimes people doubt that to be fact because Russia was isolated under the Mongol yoke and may have introduced practices that had not been part of the ritual of the Church when it came to Russia at the Baptism of the Rus. But if you understand the entire life of Old-Ritualist communities, which is almost fanatical in the adherence to the ritual of the pre-Nikonian Russian Church, then you must agree that the concept of Russian innovations becaue of isolation during the Mongol yoke is ridiculous. Consider how in an Old Ritualist community that one of the first things a child is taught is how to properly hold his fingers in the ‘two-fingered’ sign of the Cross or he will soon receive a slap on the head for doing so sloppily and then I think you can pretty much say that it’s very unlikely that random innovations entered the Russian Church before the Patriarch Nikon.

As a matter fact, it was a real revelation to me because once the Soviet Union began to fall, and once I began to see videos of Old Believers in Moscow, Romania, and in Oregon and Alaska. Certain practices in our parish that I was beginning to believe may have been our local ‘mistakes’, since they were not done in any of the New Rite parishes I visited, were dispelled when this contact was made with other Old believer communities. Let me give you an example. After “Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto the ages of ages, Amen,” we make three bows, while in the New Rite it’s only one bow. Nobody’s doing these three bows, and I’m thinking, “Maybe this is something we introduced.” Then I see it being done everywhere among the Old-Believers, who have had no connection with each other all these years. But even apart from that small thing, most people would readily admit, when the whole westernized practice of iconography really came into practice, it’s almost only the Old-Believers who preserved traditional Orthodox iconography. If you take the whole aspect of the westernized music — you may love it. And I tell people this all the time: if you come from what I call “High Russian Opera” parishes, you’re not going to like our singing. If you have some idea of what chant is like, then you might like our chant. But the preservation of the Znamenny Chant has a role. These are the reasons that our forebears bore persecutions for their choice of the Old Rite. These are still the reasons for us to preserve the Old Rite in our parish – even if we now acknowledge the Orthodoxy of Greek or post-Nikonian deviations from our ritual.

But I think, Father, as a final answer to this question, why it’s really important is that many of the people who convert to Orthodoxy in America do so on the basis of what they read about Orthodoxy. Maybe they come into a church, they hear about it they see a Liturgy — but also, if they’re zealous, they’re reading. And when they read about Orthodoxy, they have an expectation: this is the way it’s done; this is the practice. Very often, when they see the Old Rite practice, they say, “this is what I really read about, and so this is what I’d really like to do.” I can’t tell you how many people say to me, “You really need to have a primer and videos on how to sing Znamenny Chant, because we really want to sing Znamenny Chant. We understand that this is a more ancient practice.”

So I think the basic reason for preserving the Old Rite in this parish is that this is what our forefathers did, and I think there’s also a role for the Old Rite in today’s Orthodox world. And I must tell you, Father, so many things have happened over the last twenty five years that I would never have believed were coming. I believe in miracles, but I’m really more after Dostoevsky’s Father Zosima from Brothers Karamazov, who said “Faith doesn’t come from miracles, miracles come from faith.” I’m not the kind of person who walks around and sees ice cream cones that look like the Virgin Mary, and I’m even skeptical when I hear about weeping icons. I’m not saying they don’t happen, but I want to see. But my point is that so many things happened in the past twenty-five or thirty years in my parish: from this little isolated group of Pomortsy Old-Believers from Suwalki in Poland that nobody in the world knew about, to a parish that came to priesthood and had a bishop. My point is — I don’t want to sound like a Protestant – but it seems that there’s some plan of God for us and for this parish. I think we have to hold onto that. I think we should be very careful not to make some decision like “It doesn’t matter anymore whether we are Old Rite or not.” If we are not in the future, then it’s not a tragedy for the people, but I think it’s something that we really should try to hold onto. I recently had a meeting with my parishioners in which I told them: “I want you to know that if I drop dead and you should decide to move away from the Old Rite, then you will have turned away from everything I’ve tried to do as your rector (beyond, of course, caring mostly about your souls.)”

Are there any similarities between the problems you had in your parish after joining the ROCOR and, on a larger scale, those problems that we have been experiencing since the ROCOR joined the Moscow Patriarchate?

I think it’s exactly the same. You can get into this point of saying there’s never enough that they’ve done. “The Moscow Patriarchate needs to recognize the New Martyrs, etc.” The Old-Believers act in the same manner: “You need to ask forgiveness, you need to do this and that.” I think it’s very similar, and I think the parallels are amazing. I think that’s why, when I spoke at the 2006 Sobor, so many people could actually say, “You know, what he’s saying is true.”

Looking back at the time of your reception, would you say that the ROCOR’s state of mind in 1984 was similar to that of the Old Believers?

In many ways, certainly, I think that’s true. Especially in 1981 (or wherever it was) when the bishops decreed that ecumenism was the heresy of all heresies; it was — what should I call it — a mentality that we are bastioned in our forts against all the people who are coming in trying to introduce change, to change all the traditions of the Church. So in many ways it was the same, and that was a concern of mine. I should say that when I first was looking into ROCOR, if I had concerns I would say they were twofold. One is that I saw that it was so Russian. In my mind I had come to the realization, that, as we read in the end of St. Matthew’s Gospel, our Lord tells us that we need to go to all nations, to teach them and to baptize them. And again, the words we chose to surround the icon of the Pantocrator in the dome of our church remind us that that’s our mission. At that time I feared that, in many ways, ROCOR was so involved with the idea that our mission is to be Russian that it really didn’t have the concept of going out among all nations. And Old-Believers have the same kind of mentality that goes: “We are perfect. Everyone else is polluted and defiled.” And that was a concern of mine because, obviously, as an Old-Believer who was now saying, well, we’re not perfect….

For an Old-Believer to come to the determination that I did, first of all, they have to be able to look at the Council of Stoglav, which met in 1551 in Moscow, under the leadership of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, because the Stoglav Council, an All-Russian Council, had said categorically that the two-fingered sign of the Cross is right and the three-fingered sign of the Cross is wrong. Also, the Council rejected the use of the triple Alleluias and all the rest of the practices that seemed to be ‘creeping’ in from the polluted foreigners. So I had to be able to come to the point of saying, “hmm — you know what? I think Stoglav exceeded its authority. I don’t think it had the right to say what it did in certain areas, and therefore I think I can come to some sort of accommodation with the New Ritualists. I think the Church Abroad has come to much of the same kind of mentality in the past several years.

Vladyka Daniel used to like to say (not during the reconciliation, but beforehand) that he was bothered by the mentality of the Church Abroad and some of its leaders. He would say that the attitude had evolved into one in which there was the belief that ROCOR is THE Church. But, he would counter this claim by saying that the Church is universal, not merely “us.” I think that mentality was very similar to Old-Believers.

For about four decades since the death of Metropolitan Anastassy in 1965 the ROCOR has been positioning herself as the repository of unadulterated Orthodox faith, standing firm against the apostasy of World Orthodoxy. Therefore, I understand those who were deeply disturbed when this dichotomy was challenged by a more balanced ecclesiastical view. How would you respond to those who ask, “Were you lying to us then, or are you lying to us now?”

There’s two parts to that question, I think. The first one deals with the position of the Church Abroad vis-a-vis the Moscow Patriarchate. Of course, the problem was that the Church Abroad, very much like Old-Believers, made these categorical statements that they should never have made. You know, Vladyka Anthony of Los Angeles used to call the Moscow Patriarchate the “Satanic Church,” I believe. So, when you make those kinds of statements you box yourself into an untenable position. One of the things I’ve learned is that you should not say the word “never,” because things change. I think that things changed in the Moscow Patriarchate. Back in the 1980’s I had argued in an Old-Believer publication I wrote for called Tserkov, which was widely disseminated among Old-Believers in Russia, that they shouldn’t join the Moscow Patriarchate any more than I would, because I believed that there were too many things that were really improper, including the idea of not doing immersion baptisms. This is still a concern of mine. But things change; times change. We know this from the whole history of the Church. Look at the time of the iconoclasts. Among the most fervent iconoclasts were those Church figures in Constantinople. But times change, and we have to look at those changes. So, in that first instance, I don’t think that ROCOR lied: it’s just that things change, and you have to open up your mind and heart to those changes.

Now I think that there certainly are still elements that were and are aeas of concern of the Church Abroad vis-a-vis the other Orthodox Churches. Let’s call them ecumenism or modernism or whatever the case is. As an Old-Ritualist I would readily say that I am still concerned about those, but I’m not so sure that one can take this position that that means they are not Orthodox and we should not be talking with them. As a matter of fact, even when we were isolated from the rest of the Orthodox world, when I met Metropolitan Theodosius of the OCA (and I met him a couple of times at exhibits in Washington) I asked for his blessing. I had an OCA priest come to my church years ago on Bright Tuesday who wanted to go into the altar and venerate the altar before the service, and I let him. I had a man who was a convert, who actually didn’t convert through our church, but came in through the regular ROCOR Church, who was so scandalized that I let this OCA priest come into my altar, that he left and joined the Matthewites. Well, my mentality toward that, again, is: that’s your lack of understanding, rather than the true understanding of the Church. So I think that, in some ways, our decision to isolate ourselves may have had some validity but, I think, we can look at it and say, times change. People’s attitudes change, and we now have to dialogue with the other Orthodox Churches. In the case of Moscow, we have to recognize that they changed, and they did what we asked them to do.

When the seminarians and I visited your parish. We were impressed by the volume of volunteer services that your parish provides to the local community. Can you tell us what social projects your parish runs and how a typical small ROCOR parish can initiate something similar?

We Orthodox Christians, probably because of our own sin of pride, often make comments that, very often, let’s say in Roman Catholic Churches now, and even Protestant Churches, they’ve become more social agencies than repositories of salvation. And we really need to understand, of course, that the first goal of the Universal Church and also of the parish church is to save souls. That’s its first goal. But we cannot deny the fact that when our Lord comes back — and we know this from chapter twenty-five of St. Matthew. — He makes very clearthat his questions to us will not be ones such as: “Did you have a beard? Did you say the Vigil? Did you make prostrations?” He says “Did you feed the hungry? Did you clothe the naked? Did you give drink to the thirsty?” And so we know that Christian love and charity really is a prime obligation of the parish. We try very hard. I don’t think we did it well years ago, and we still have far to go in this area, but we’ve tried in the past thirty years. We work certain days, for example, at the Benedictine-sponsored soup kitchen. They have different groups come in every day and serve meals for the poor. Our parish serves at that soup kitchen one Friday every month. We serve at that soup kitchen on Western Christmas so that the nuns can celebrate their Christmas and the poor still have a place to have dinner on December 25th. We deliver food baskets to maybe forty, fifty, sixty families at Western Christmas so they can celebrate Christmas and have food enough to eat. We run a food pantry and are now delivering food to maybe forty or fifty families every other week so that they have enough food in their community. Even though it’s during the Nativity Fast, we have a Christmas party for about one-hundred and fifty really indigent children who are mostly from homeless families who have nothing, so we can give them something during Western Christmas. So there’s many ways that any ROCOR parish, even a small parish, can do things that don’t cost you a lot of money. In fact the food pantry I mentioned for the fifty families may sound really admirable, but there is a food bank here in the area, with most of the food being provided by them, and so we’re not paying for the food. We’re simply picking it up, distributing and so forth. Therefore, we can’t make the argument that we can’t afford to do that. It simply comes down to the fact that we can’t afford not to do this, because, once again, as we discussed earlier, how will we answer the Lord and say to Him, “But Lord, I didn’t know it was you.” If we do that, He will say to us, “Go onto the left side and be with the goats rather than the sheep.”

Now that we can no longer claim the exclusiveness of the Russian Church Abroad, what should be our mission within both the Russian Orthodox Church and Orthodoxy in Northern America?

That’s a very interesting question, and one that I guess I should be use discretion answering. I prefer not to get myself into trouble, but I will answer honestly. I do think we must be very careful. We understand, of course, that the Church Abroad was founded by immigrants who fled because of persecution. The goal of the Church Abroad was primarily to preserve Russian Orthodox Christianity and also to preserve Russian Culture — and that was a valid goal. Now that we’ve reconciled with the Church in Russia, we really no longer need to be the repository of Russian culture and the Russian Christianity. What we need to be now is the Church i that sees itself as being the repository of Orthodox Christianity for those outside of Russia, not only for Russian immigrants, and for second, third and fourth generation Russian people, but for the converts in many places who are coming into Orthodoxy. Vladyka Daniel used to be very adamant about the idea that some decades ago our mission changed. It was no longer to preserve Russian culture and Orthodoxy until we could go back to Russia (because most people haven’t), but that we see our role as this: Orthodox Christianity is the faith of our fathers, and we believe that it is the true heir of the Apostolic Church. Thus, our mission now is to offer Orthodox Christianity as an alternative for all those who are dissatisfied with the Christianity that is found in the West.

So I think that our mission now is really much more than merely the idea of reinvigorating our Russianness. Certainly we should rejoice in the fact that we are agin united with our co-religionists in Russia, and we should share in that common faith with those in Russia, but we must make sure that they understand and that we understand that our mission is to be Orthodox Christians outside of Russia and to bring the word of God to those people in our adopted countries who look to Orthodoxy as an answer to their spiritual needs.

It seems that we now need to convene the Fifth Pan-Diaspora Council, which would express the voice of the Church regarding a broad spectrum of questions, from relations with other Orthodox Churches to various ecclesiastic practices. What are the most pressing problems that the ROCOR faces now?

The most important obligation, function, service of the Church is to provide the faith of Christ, the Church of Christ, the Body of Christ, to all of its believers and to those that need that faith. But from, let’s say, a more practical standpoint, I think one of the things that ROCOR really needs to do — its bishops, its clergy, its laity — is that we really need to come to understand where we stand in regard to the rest of the Orthodox Churches. There is still great confusion here. Are we in communion with the OCA? Are we in communion with the Greek archdiocese? With whom are we in communion? What does that mean to be in communion? Are we serving with them? Do they serve in our churches?

We must also, I think, dialogue with them in order to speak to some of the areas about which we are concerned. I express this all the time to my friends in the OCA. I have great respect for many of them. I know many of them are very pious Orthodox Chritians. But I know of many OCA parishes where there is no Vigil or Vespers being served, and I say, “Where in the Church did it ever indicate that the Vigil is no longer important?” I had a cousin who moved to South Carolina. He and his family are now going to a good OCA parish down there. But he visited me shortly after Pascha and was with me for a Vigil on the Sunday of the Myrrh-bearers. As we were singing the Paschal Canon, I went to him and said, “It just occurred to me. In the vast majority of OCA parishes, where they never serve Vigils and never serve Matins, you never hear the Paschal Canon after Pascha morning!” That’s a terrible tragedy, not to hear the Paschal Canon, because it’s the canon that really provides the fullest sense of the meaning of our Lord’s Resurrection.

So I think ROCOR has a need to clarify where we stand and also to play a role in speaking to these confusing issues in world Orthodoxy. We need to express to them that “We know that we cannot take the position that we are the only pure, true faith. We understand that may have been an error.” But that does not mean that we simply pretend that there are not issues that need to be addressed with our Orthodox brethren in other Churches that have disregarded many of the age-old practices of the Church Universal. I really admired Vladyka Mark of Berlin, because at the 2006 Sobor he started his address to the Sobor bysaying, “We made mistakes.” But at the same time we have to be courageous enough and true to ourselves to say that there are things that we have preserved in Orthodoxy that other Orthodox Churches have lost, and we should say, “We will compromise in certain areas, but we expect you also to return to the Tradition of the Church in certain areas where you have allowed it to be disregarded. For example, where did the concept of eating dairy products in fasting seasons or on fasting days originate? Or whoever heard of the Church granting ‘dispensation’ to eat non-fasting foods once a fast has begun?” I should use the term ‘compromise’ carefully. I don’t mean compromise in basic tenets of the faith, but perhaps to say, okay, we’re willing to have joint communion with you, some adjustments. We’re still not completely comfortable with what you’re doing. There’sare things that you’re doing that you need to recognize aren’t very traditionally Orthodox, and you need also to move back in that direction as well. But I should be careful with the word ‘compromise’, lest I be misunderstood.

Please accept our sympathy on the loss of your beloved archpastor Most Reverend Bishop Daniel. How is your parish going to live without him?

He was a tremendous benefit to our parish. Sadly, however, I think most people are unaware that from the time he actually moved here and became a regular part of the parish, he was already quite ill. Shortly after he moved here he had a heart attack and he had strokes, so he lived here in a debilitated condition for most of his pastoral time here, when he actually was the bishop living in Erie. So most people didn’t have the opportunity to appreciate and really know what a brilliant man he was and what a great shepherd he was. I had that opportunity because, when I first knew him he was already ill but he still had all of his mental faculties and his ability to show great discernment and great teaching. There is no way you can replace Vladyka Daniel. I was grateful to Fr. Victor Potapov that in one of his recent newsletters he wrote such a deeply moving eulogy for Vladyka Daniel. Fr. Peter Perekrestov recently wrote a eulogy that was going to be, I think, in the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, which is also really wonderful. These are people who recognize the great stature of Vladyka Daniel. We are now in the process of determining the fate of a future Old Rite bishop in ROCOR. There are two steps of course. The first being to find out whether Metropolitan Hilarion and our bishops are willing to again consecrate a bishop for the Old Rite. That’s the first question that has to be determined. And then we are also looking into the question of whether we ourselves can do it. The fact is that we are the only parish in the Church Abroad, at least right now, that are Old Ritualists. It’s an expensive proposition (having a bishop – A.P.) We have to look into that. But, whomever we find as another bishop, I’m sure he will be a wonderful shepherd, if we choose one. But still it will be very difficult for anyone to fill the shoes of Vladyka Daniel.

Could you please outline the significance of Bishop Daniel to the Russian Church Abroad.

I think that Vladyka Daniel showed great discernment in that time that you’ve spoken of father, that is the time of this sort of isolated fortress mentality: “We are the Church. Everyone else is wrong!” Vladyka Daniel always had a very open mind. That’s not to say that he should be classified as some “liberal.” But Vladyka Daniel would never agree to the posture that the Moscow Patriarchate was without grace. In fact Vladyka Daniel would become very animated when this suggestion arose. He would say: “What does ‘grace’ mean? ‘Gracia’ is a gift from God. Who are we to make this determination that someone is without grace?” So I think he manifested a very sensible posture in the whole question of what the Church is about. That was a great factor. There were people who knew him and understood that. Vladyka Jerome often talks about the effect that Vladyka Daniel had on his own way of thinking, on his upbringing. Certainly, there were other contributions, like the fact that he was a wonderful architect. He designed the Cathedral in Washington. He designed a church in Connecticut. He was a master iconographer. As a matter of fact, since his death I have looked at some of his icons more than I did before, and have come to realize that these are truly superb icons. He was man who, as Fr. German Ciuba said in his eulogy, also taught that you can be a man of great prayer, of great spirituality, of great theological knowledge, but can still have interests in life that go beyond that. Vladyka Daniel loved sailing. When he moved to Erie years ago, he was in the process of building a sailing ship because he wanted to sail into the port of Erie, since he was the bishop of Erie. He had great interest in cannons (yes, cannons, not “canons” – A.P.) He had great interest in many other things – even weapons. He had a cannon in his house and he would shoot it off on the Fourth of July. So he had tremendous abilities in many various areas. And yet one should never underestimate the fact that he primarily was a man of the Church. He knew every kind of chant. Kievan Chant, Znamenny Chant, Rumanian Chant, Byzantine Chant. He was an expert in every kind of chant one could imagine. He was multilingual. He was an exceptionally brilliant man, and yet he was, first of all, a man of great prayer.

The other aspect of Vladika Daniel was that, although not born an Old Believer, he felt it critical for the Church to preserve the Old Rite. In our first meetings when he saw that I was anxious to find a way to restore priesthood, he chastised me if he felt that I was in any way willing to do so at the cost of compromising the sole usage of the Old Rite in our parish services. Bishop Daniel said to me on a number of occasions, “You need to realize that your ancestors were people who really died for this. They died. They were persecuted. You know, Old-Believers can exaggerate their position a little bit, but they were persecuted.” And he also said to me many times when he knew that, after hearing the Byzantine chant at Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston, I liked many of the chants there such as “Christos Anesti”, “You may like all these things. If you want to do them, if you want to introduce other things, if you want to short-cut, and so forth — then go somewhere else, because your obligation here is really to preserve what your ancestors gave to you. You have to avoid short-cuts and the introduction of those things that are not part of the Old Rite of the Russian Church.”

Perhaps I should add that in August of 1982, when I came back from Ipswich and I was leaning toward priesthood, I actually got in touch with Fr. Dmitri Alexandrov, whom I knew at that time. I knew that he served for Old Ritualists and that he put out an Azbuka. I had questions that needed to be answered and He actually came to Erie on the 26th of August, two days before the Dormition. I had him come here to say to him, “What about the change made to the Creed after the Patriarch Nikon that the Old Believers so opposed?” And I also had other questions that I posed to him and that he answered clearly and succinctly. I had to satisfy myself that, in reality, I was not actually just doing what was pragmatic. I wanted the priesthood, and therefore it would be easy to not ask the difficult questions and to simply accept whatever, so that we could have priesthood. But as an Old-Ritualist/Old-Believer could I hide all these issues such as the propriety of the three-fingered sign of the Cross in contrast to the two-fingered sign of the Cross. I may have thought that something that we’re doing makes better sense than the New Rite, but could I truly satisfy my conscience that there’s heresy had not been introduced into the post-Nikonian Church and that I’m not really betraying the faith of my forebears?. After that meeting with Fr. Dmitri (later Vladyka Daniel) in August 1982, I felt absolutely convinced at that point that I was not betraying the faith of my fathers.

Vladika Daniel said something really interesting to me one time. He said, “Many priests decide they can skip this, they can skip that. There’s only one area of discretion given to the rector in the service books. This discretion is whether or not to serve a Vigil. There’s no discretion to skip or alter any part of the services.” I’d like to share a final story with you. We were flying to Russia and then to the Holy Land in 1993. First we were flying from Toronto to St. Petersburg. The airline had great problems getting our reservations correct. They kept mixing them up. Finally they got them right but they said, “Because we did this, we have to put several of you in first class.” I’d never flown in first class and I doubt that I ever will again. Well, Vladika Daniel was next to me on the flight with some other parishioners. We were flying on a Saturday night. We knew we couldn’t do the normal Saturday services because of our flight, but the night before we had done Vespers and Matins, then Liturgy that Saturday morning, kind of to make up for what we couldn’t do Saturday night. So I’m sitting in first class thinking to myself, “I’m in first class, they’ve got these plush seats. They’re serving champagne. There’s going to be a movie. This is going to be wonderful.” But Vladika Daniel sits next to me and, all of a sudden starts reciting Vespers and Compline by heart, without a book. And of course I sat there in the next moment thinking, “Oh I think I’ve got to sit here and pray and not drink champagne on the flight.” So that was Vladyka Daniel. There was never a time, with his other interests, that he wasn’t a man, first of all, of prayer. He served daily Vespers, Hours and Typica in his house chapel. He could recite everything by heart. Shortly before he died, he was just reciting everything by heart. He was a man of great prayer and a man of great wisdom and a man of great discernment.

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev

Thank you for this excellent interview. Many years to Fr. Pimen, and his holy efforts for and in the Church of Christ. It seems that the great pitfall of modern liturgical reforms is the divorce of liturgy and asceticism, because the liturgical life really dies without fasting. The classical pitfall of an isolated asceticism, on the other hand, is pride and self-sufficiency (pre-Nikonian Russian church literature offers ample examples of this). Fr. Pimen is an inspiring example of avoiding both, and so is the `Nikonian` Jordanville he visited. May we be united, according to Fr. Pimen`s example, – not in the number of Alleluias, or fingers used to make the sign of the Cross, but in spiritual struggle in both humility and Christian charity!

Just found your most excellent website, and immediately from this interview I know that I will be back many many times. I agree absolutely with Fr. Pimen`s balanced approach to our holy Tradition, and to our Church Abroad`s mission– which, as Met. LAURUS of thrice-blessed memory once said in an interview, is– nothing less than the Great Commission. The innovationist laxity at SVS and other places is a sign of spiritual moribundity, but this hasn`t affected everyone in that jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church. Repentance is always possible, and line between spiritual health and spiritual illness runs through every diocese, every parish, even every human heart! I am going to promote this site on my own humble blog, and will tell all of my friends and my priest. Thank you for your excellent work!

I highly recommend this interview as it describes in detail the journey of this community of priestless Pomortsy Old Believers into ROCOR. Of particular interest to me was his understanding that the Old Believer schism is very much of the same substance as the Old Calendarist schisms and the schism of those who left ROCOR recently over the reunion with the MP. It was also meaningful to learn about his discovery of the Apostolic Fathers which convinced him that there can be no Church without a bishop. A third comment he makes in the interview that I found significant was that when he took over the community in Erie while they were still Pomortsy and he began to read the service books, he came to see how much of the content of the services they were missing entirely just by not having a priest, and that these “omissions” were much more significant than any of the ommissions or abbreviations which resulted from the Nikonian reforms.

Excellent interviewing Dn. Andrei.

Thank you, Reader. I hope you found my Patreon podcasts useful.

It’s tragic to see that they now serve almost entirely in English now at the Erie church and buy into renovationist nonsense, e.g., infrequent communion being a late medieval invention. I find it very ironic that you quote Vladyka Daniel “you need to realize that your ancestors were people who really died for this,” and then start leaning on English Orthodox materials that are riddled with Protestantisms and positively speak of Schmemann, Meyendorff, and Hopko. It’s too bad that people are abandoning their ‘Russianness’ in the name of a more ‘Cosmopolitan’ Orthodoxy, because one’s ancestry is part of what makes one human. By embracing American rootlessness you are not only betraying your ancestors but also betraying your children, denying them one of the few things that can never be found in a book or bought in a store. And for an Old Believer to accept such a Protestant, colonial interpretation of ‘the Great Commission’… how does preaching the Gospel necessitate forgoing one’s essence and heritage? I assume they won’t be saying Litanies for Dead soon, because their beliefs lead to that. And if people want to throw around the word ‘mission,’ let me teach you that the word mission entered both English and Russian via the Jesuits. The word mission can be found nowhere in the KJV bible and the Church Slavonic word Мисия refers to a city in Anatolia. In fact, keeping one’s ‘Russianness’ is even more true to the Gospel because it teaches otherwise rootless Americans how they should view themselves and how they should seek to imbue their lives with depth and history. If you disagree with this then I recommend that you meditate on the genealogies of Christ in Matthew and Luke and consider why the book of Numbers spends so much time ‘boringly’ enumerating ancestors and tribes. No saint could have imagined a society not founded on one’s ancestors like this one, it’s sad to see an Old Believer group of all people fall for that poison too.

Orthodoxy has always used the vernacular language. Use of English doesn’t betray any canons.