Mikhail Bogdanov was born to the family of a priest on the Ryazan Province on 6 Nov 1857. He attended the Kazan Seminary, graduating in 1888. Thereafter, he was appointed a sacristan and tonsured a reader. He was married sometime after the graduation, and subsequently ordained to the priesthood on 22 Nov 1892. He served as Rector of the Saints Kyril & Mefody parish in Kazan during the years 1895-1896. In 1896, his wife reposed, and he decided to continue his education at the Kazan Theological Academy. Following his graduation from the Kazan Academy in 1900, he was appointed to a management position at the Russian Teachers Seminary in Poretsky. [1]http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Михаил _(Богданов)

In 1902, he accepted monastic tonsure with the name ‘Mikhail,’ and was appointed as Inspector of the Kharkov Seminary. In 1905, he was elevated to Archimandrite, and appointed as Rector of the Kazan Seminary. He was awarded a Doctorate of Theology in 1906, for the work presented as his thesis, “The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ, Exegetical Studies of Chapters XVII and XVIII of the Gospel of the Holy Apostle & Evangelist Matthew.” This work was later recommended to be read in “educational institutions in Russia.” [2]ibid.[3]http://drevo-info.ru/articles/3807.html

On 30 Aug 1907, Archimandrite Mikhail was consecrated to the Episcopate as Bishop of Cheboksary, Vicar of the Kazan Diocese. The consecration was concelebrated by Archbishop Dimitri (Dimitri Ivanovich Sambikin, 3/15 Oct 1839-7/30 Mar 1908) of Kazan & Sviazhsk, Archbishop Nazary (Nikolai Yakovlevich Kirillov, 4/16 Dec 1850-2 Jul 1928) Archbishop Nazary served in close proximity with three well-known hierarchs of the Church Abroad: he succeeded Archbishop Feofan (Gavrilov, 1872-1943, who took the Wonderworking Kursk Root Icon of the Most Holy Mother of God outside of Russia) as administrator of the Kursk & Oboyansk Diocese, and was named Metropolitan of the Diocese in 1925; Archbishop Nazary also preceded one of the Church Abroad’s most eminent and respected Hierarchs, Archbishop Feofan (Bystrov, 1873-1940) as head of the Diocese of Poltava & Pereyaslavl from 1910 to 1913; he also preceded Archbishop Platon (Rozhdestvensky) as Bishop of Kherson & Odessa from 1913 to 1917. Later Metropolitan, Platon was an early and stalwart supporter of the Church Abroad, only to leave in schism in 1927; Platon headed the North American Metropolia until his repose in 1934. Metropolitan Nazary was arrested and imprisoned in Solovki in 1927, and reposed in 1928. [4]http://www.pstbi.ccas.ru/bin/nkws.exe/no_dbpath/ans/nm/?HYZ9EJxGHoxITYZCF2JMTdG6XbuBc8SUs8Wd60W8eC0ceuiicW0Be8eieu0d8E*

Archbishop Dimitri of Kazan & Sviazhsk was an illustrious Hierarch of the Russian Church. He had been raised “piously, in obedience to Faith in Christ.” During his eight years as Rector of the Tambov Seminary, it became known as one of the best in Russia. In 1867, he was awarded a Master’s Degree in Theology; in 1893 named a Member of the Moscow Theological Academy, and in 1895 a Member of the Kazan Theological Academy. In 1904, due to outstanding scholarly and literary works, he was awarded the Degree of Doctor of Church History by the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy. He did much Church Archaeological work, finding and restoring many of the historical churches of the Tver Diocese while he was Bishop there (1896-1905), and founded the Kazan Church Archaeological Society when transferred to Kazan. He was the author of many works, including a Menologion of All the Saints of Russia; Lives of Bishops of the Voronezh Diocese; Histories of numerous monasteries; a history of the Tver Diocese; the Tver Patericon; the Lives of numerous Saints and hierarchs of the Russian Church; several works on the history and parishes of several Russian cities; complete services for the Feastdays of the Twelve Apostles, and the Seventy Apostles; the Akathist to Saint John Chrysostom; and many, many more instructive homilies, essays on the spiritual life, as well as historical and archaeological works. In the 1907 Chronicles of the Diocese of Kazan, he published a homily, “On the Deliverance of the Staff to the Newly Consecrated Bishop Mikhail (Bogdanov) of Cheboksary,” which was delivered at Bishop Mikhail’s consecration. Several biographical works on the life of Archbishop Dmitri were published, including an Obituary and Funeral speech delivered by his Vicar, Bishop Mikhail (Bogdanov) of Cheboksary at a Memorial Service for Archbishop Dimitri in Kazan on 21 Mar 1908. Bishop Mikhail continued to serve as Bishop of Cheboksary until 1914. [5]http://www.tver-antonievmon.narod.ru/monfales/Fales/persona6.htm[6]op cit., 1[7]op cit., 1

On 11 Jul 1914, Bishop Mikhail was appointed as Bishop of Stavropol & Samara. The Province of Samara, in the 1897 Census, had a population of 2.75 million, with 1.35 million men, and 1.4 million women. Single people-“bachelors and maidens,” were the majority, with married people being the second largest group. The province was 76% Orthodox, 10% Muslim, 5% Lutheran (Volga Germans), 3% Old Believers, and 2% Roman Catholic. Various Protestants and Jews accounted for less than 1% of the population. 92% of the population was considered as “rural,” with 85% earning their livelihood by “farming.” The literacy level was highest among Lutherans, Jews, Catholic and Old Believers, ‘middling’ among the Orthodox, and lowest among the indigenous Chuvash. The city of Samara had a population of 90,000. [8]http://kraeham.livejournal.com/43819.html

Saint Alexey, Metropolitan of Moscow, is said to have visited the site of Samara in 1357, predicting that a great city would be built there; he was later named as the Patron Saint of Samara. By the 17th century, Samara was a center for diplomatic and economic links between Russia and the East. Reflecting the peasant/agricultural predominance, Samara opened its gates to the peasant rebels Stenka Razin and Emelyan Pugachev, greeting them with bread and salt. Previously part of the Simbirsk Province, Samara became capital of a Samara Province established on 1 Jan 1851. The great economic growth of Samara during the 19th and early 20th centuries was due primarily to the “bread trade and flour milling” enterprises. In the 1880s, the Samara Brewery, a macaroni factory, an ironworks, and a confectionary and match factory were all established. Samara wheat was exported internationally. Its rapid growth in business and industry led Samara to become known as ‘the Russian Chicago.’ By 1900, Samara was the main center of trade and industry in the Volga region. [9]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samara,_Russia

Bishop Mikhail, as one of the most well educated hierarchs in the Russian Church at that time, emphasized the education and formation of youth. The Romanovsky Educational Foundation originated upon his advice. This Foundation awarded three hundred stipends per month to gifted children of the parish clergy. From the very commencement of World War I, Bishop Mikhail did everything in his power to aid the war wounded and refugees escaping into his diocese in great numbers from areas under German occupation. All the monasteries of the Diocese had opened hospitals for the wounded. There were seven almshouses in the Diocese, and two of the Monasteries distributed food to an average of 75 people a month. The Diocese organized a Committee to assist soldiers and their families, and a Committee to place refuges in housing after their arrival in the Diocese. [10]http://samara.orthodoxy.ru/Istoriya/Istoriya.html

The Samara Diocese included 986 churches, 13 of which were Cathedrals; 1,059 two class schools, and 12 Parish craft schools in the Monasteries. The total enrollment in these schools was 69,729; especially in the rural areas, the Church was primarily responsible for the education of children. There were nineteen Monasteries, seven for men, twelve for women. The total ‘white’ clergy in 1916 numbered 3,021. There were 967 Parish Libraries which held a total of 142,535 volumes. The Diocese published three periodicals, “Dukhovni Sobesednik,” “Samarskie Eparkhialni Vedomsti,” and “Samarskii Khronograf.” These statistics were drawn from reports in Bishop Mikhail’s own hand that he compiled and sent yearly to the Holy Synod. [11]ibid.

During Bishop Mikhail’s tenure in the Samara & Stavropol Diocese, the most noteworthy occasion in the Diocese was the consecration of the new Saint Michael the Archangel Church in the village of New Orenburg. The new stone church was built alongside the old wooden one. The event was made especially festive due to the presence of Bishop Mikhail’s predecessor as Bishop of Samara & Stavropol, Metropolitan Pitirim (Oknov) of St. Petersburg. The choirs of the Iveron Convent and the Seminary sang during the services, and fifteen thousand worshippers crowded the new church and adjoining streets, all joining the procession from the church to the Chapel of Saint Alexis at the train station to bid farewell to Metropolitan Pitirim on his departure for St. Petersburg. [12]ibid.

The fall of the Imperial Government, and both the subsequent Provisional and Bolshevik governments brought harsh restrictions to the Church. The Decree on the Separation of Church and State effectively abolished the system of Church operated schools, and the Diocesan Seminary was closed. [13]http://www.saminfo.ru/~samds/Text/Vertical/Library/K_ubil/2.htm

Bishop Mikhail attended the All Russian Church Council of 1917-1918. After bolshevik demands on church properties and valuables, Bishop Mikhail created a series of proclamations prohibiting the desecration of holy objects, and led a procession on 28 Jan 1918 to illustrate the people’s opposition to such desecrations. [14]op. cit. 3

The Russian Civil War, often seen as a simple struggle between Red and White, was a great deal more. The ‘Whites,’ as all anti-bolshevik governments and forces were called, were anything but united or homogenous. The number of ‘White’ governments established during the Civil War across the length and breadth of the former Russian Empire were nearly countless, and ranged the entire political spectrum, from the ‘classic’ White Russians who wanted to restore the Autocracy, to those who hoped for a Constitutional Monarchy, to those who hoped for some type of Democracy or Republic, to moderate Socialists, to left Socialist Revolutionaries who promised all land to the people and that ‘the landlords would never return.’ Anarchist military formations, such as Nestor Makhno’s ‘Greens’ in Ukraine fought against the bolsheviks as well as the pro-Monarchist Whites. There were several ‘White’ formations presided over by Cossack warlords whose agenda was power and self-enrichment, and whose brutality rivaled that of the bolsheviks. To further complicate matters, there were the numerous nationalist factions-Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians, Estonians, Latvians, Finns, Poles, Azerbaijanis , Central Asians … the list was seemingly endless. The Western Allies intervened, mostly haphazardly and ineffectively. Eastern European nations sought Russian territory taken from them in earlier conflicts; the British, French, Americans and Japanese sought ‘spheres of influence’ and Russian natural resources. If one were to simply tally up the opposition to the bolsheviks ‘on paper,’ it would seem an absolute miracle that they prevailed in the end. The absolute refusal to cooperate, or cooperate for any meaningful amount of time between various of the ‘White’ forces (even those ‘ideologically compatible’) all but guaranteed Red victory.

On 8 Jun 1918, Samara was occupied by the Czech Legion, another of the ‘wild cards’ to appear in the Russian Civil War. The Czech Legion was originally created by the Imperial Russian Government, made up of Czechs and Slovaks who had previously settled in Russia. They hoped for the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and subsequent creation of a free Czech and Slovak republic. Their numbers were increased after the 1917 February Revolution by prisoners of war from Austria-Hungary in Russia who had volunteered to fight with the Allies against Germany & Austria-Hungary, released by the Russian Provisional Government to do so. These soldiers wished to aid the French, English and American fight against the Germans, by re-opening an Eastern Front. Because of the recently signed Brest-Litovsk Treaty between the new Soviet state and Imperial Germany, the bolsheviks would not allow a reopened Eastern Front to aid the Allies. They did, however, allow the Czechs to travel through Siberia to meet Allied ships at Vladivostok; the plan was to then transport them to the Western Front, and aid Allied efforts there against the Germans. [15]Lincoln, W. Bruce “Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War” New York 1989 pp. 93-94

Due to both bolshevik attempts to disarm the Czechs and wishes of the Western Allies, the Legion was transformed into an anti-bolshevik force. The Czechs did not want full participation in a Russian Civil War, but they were determined to leave Russia via Vladivostok, no matter what it took. They were well armed, disciplined professional soldiers, and the bolshevik forces between them and their goal were not; there was little question of the bolsheviks stopping the Czechs by force. Of course, the Czechs were merely passing through, and had no intention of establishing governments or authorities in the places they did pass through. After forcing the bolsheviks from Samara, the Czechs had no wish to govern. They had no objections to the Komuch government to assuming power. [16]ibid.

The Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly-known by its Russian acronym, “Komuch”-“proclaimed an independent government the moment that units of the Czech Legion drove the Red Guards out of the Volga River city of Samara.” The Komuch Government was formed of members of the Socialist Revolutionary party who had been delegates of the Constituent Assembly which had been dissolved by the bolsheviks. [17]Lincoln, p. 100 The SR’s, ”had sprung from neopopulist roots that had little consistency other than a longstanding dedication to the abolition of private land ownership.” [18]Lincoln, p. 119

SR’s greatly outnumbered both the bolsheviks and mensheviks; however, they had little unity, and their left, center and right factions were “perpetually on the brink of schism,” and they had “intensified their feuds” during the short lived Provisional Government that preceded the bolsheviks. [19]Lincoln, p. 118 Komuch, then, was not typical at all of what is commonly thought of as the ‘White Russian movement.’ They were diametrically opposed to the restoration of the monarchy, and, for the times, were, indeed, as their name stated: a Revolutionary party. That being said, it must also be stated that during the Russian Civil War, the SR’s center and right factions were equally as opposed to the bolsheviks as they were to the ‘old order.’ [20]Lincoln, P. 101

The Komuch government , however, did abolish all persecution of the Church, stated that the time for ‘socialism’ had not yet come, and returned private property, landlords, factory owners, etc., that had been expropriated and dismissed by the bolsheviks. They also sought aid from the Western Allies against the bolsheviks, in exchange for promising to return Russia to the war against Germany. [21]op. cit. 13[22]Lincoln, p. 100

The situation within the Church sometimes seemed just as fragmented. There were Bishops and clergy who supported the Provisional Government, and even welcomed its appearance, and its program, after the abdication of the Tsar. Some Bishops also supported various ‘governments’ consisting of SR’s, similar to the Komuch government. This support may have been by conviction, or simply looked at as a requirement in the situation. At any rate, Komuch did not last long in Samara. By September 1918, the First Red Army commanded by Mikhail Tukachevsky had crossed the Volga, and the Komuch forces were deserting to the Red Army at a rate of some 200 men a day. The bolsheviks reoccupied Samara in October 1918. Bishop Mikhail departed eastward with the anti-bolshevik forces. [23]www.rocorstudies.org/test Lives of Bishops/Bishop Mikhail (Kosmodamiansky)[24]Lincoln, p. 190[25]op. cit. 13

Bishop Mikhail travelled from Samara, through Siberia, to Vladivostok. Siberia was under the control of various and numerous entities: the SR Provisional Government of Autonomous Siberia in Omsk (akin to Samara’s Komuch government), the Czech Legion was a sort of “moving government,” keeping some semblance of order along the way as the Legion moved towards Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian railways; a “Provisional All Russian Government” declared in Ufa in September 1918, ran by a five member “Directorate;” the dictatorship of the Supreme Ruler Admiral Kolchak, supported by 100,000 Allied troops, primarily from England and Japan; and the Cossack Warlords, “the corrupt and rapacious Siberian Cossack Ataman Grigorii Semenov,” and the Ataman Ivan Kalmykov, who “fought their own campaigns for their own purposes in Siberia,” supported by the Japanese. Also, in the larger cities with any industry, there was no shortage of support for the bolsheviks. [26]Lincoln, Ch. 7 It doesn’t take much imagination to conclude that Bishop Mikhail’s journey from Samara to Vladivostok was neither a particularly comfortable, nor safe journey.

In December 1918, Bishop Mikhail assumed the administration of the Diocese of Primorsk & Vladivostok. He was appointed as Bishop of that Diocese in 1919, by the Provisional Supreme Church Authority of Siberia [27]op. cit., 1 , organized along the same lines, and for the same reasons-inability to communicate with Patriarch Tikhon-as the Temporary Higher Church Administration of South Russia that was the forerunner of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. Patriarch Tikhon himself had foreseen the need for such measures, and provided for such a situation: “Seeing that the persecutions were intensifying, and that the time could come when the central church authority would find itself separated from the local church administrations, the Patriarch, together with the Holy Synod and the Higher Church Council, issued the ukase (#362) of November 20, 1920. The ukase reads: ‘In the event that a diocese finds communications with the Higher Church Authority broken, or the Higher Church Authority headed by the Patriarch, for some reason ceases its activity, the diocesan bishop shall immediately contact the bishops of the neighboring dioceses with the object of organizing a higher unit of church authority … in the event of this being impossible, the diocesan bishop must take upon himself the fullness of power.’ Point 3 of this ukase states that this higher unit of church authority must be headed by the senior of the Hierarchs.” [28]M. Rodzianko “The Truth About the Russian Church Abroad (The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia)” Translated from the Russian by Michael P. Hilko Jordanville, New York 1975 pp. 37-38

The Vladivostok Diocese was very different from Bishop Michael’s Samara Diocese. In 1912, it was approximately a tenth of the size of the Samara Diocese, with 127 churches, two monasteries (one women’s), and 107 church schools. While these statistics probably had not changed a great deal since 1912, the population of the Diocese had increased greatly since the beginning of the Civil War. As a major port, Vladivostok was overflowing with refugees hoping to leave Russia, and those simply hoping to escape the clutches of the bolsheviks in what was to become the ‘last refuge.’ [29]http://www.ortho-rus.ru/cgi-bin/or_file.cgi?3_443

Admiral Kolchak’s tenure as Supreme Ruler lasted only until January 1920, when he was turned over to the Menshevik and SR “Political Center” in Irkutsk by the Czech Legion. It was ordered by Lenin himself that Admiral Kolchak was not to be executed, but kept safe for a trial. Fearful of Kolchak’s rescue by White forces, the Irkutsk Cheka executed him on 7 Feb 1920. Vladivostok held out until the end of October 1922. [30]Lincoln, p. 267

In 1921, after the conclusion of the Karlovsty Council that established the Russian Church abroad, Archbishop Innokenty (Ivan Apollonovich Figurovsky, 1868-1931) of Peking and China requested that the Higher Church Authority Abroad approve nomination of Archimandrite Simon (Sergei Andreyevich Vinogradov, 1876-1933, later Archbishop of Peking & China) as Bishop of Shanghai, Vicar of the Diocese of Peking & China. On 4/17 Jan 1922, the nomination Archimandrite Simon was accomplished, along with the creation of the Vicariate of Shanghai for the Peking & China Diocese. This was the earliest official contact between the Higher Church Administration Abroad and the Hierarchs in the Far East. Some other decisions concerning the Far East were also made, which clearly illustrated the comprehensive and unquestioned authority of the Higher Church Administration Abroad. One of these decisions was the creation of the Harbin & Manchuria Diocese in Mar 1922. The new Harbin & Manchuria Diocese encompassed some areas that had previously been part of the Primorsk & Vladivostok Diocese. This caused Bishop Mikhail to protest against the creation of the Harbin Diocese. His protest was acknowledged, but the decision stood. Bishop Mikhail accepted the ruling acknowledging, but overruling his objections. [31]Seide, Father Georg “History of the Russian Church Abroad” manuscript revision, pp. 37-38

On 22 April 1922, Bishop Mikhail participated in an episcopal consecration in the new Harbin & Manchuria Diocese. At that time, Archbishop Mefody (Gerasimov, 1856-1931, later Metropolitan) of Harbin & Manchuiria, Archbishop Melety (Zaborovsky, 1869-1946, later Metropolitan of Harbin & Manchuria) of Chita & Transbaikal, and Bishop Nestor were residing in Harbin. Bishop Mikhail travelled from Vladivostok for the consecration, only weeks after the final confirmation of the creation of the new Harbin Diocese. An Archpriest from Chita, Sergey Starkov, was tonsured on 1 Apr 1922 with the name Sophrony (in honor of St Sophrony of Irkutsk) by Archbishop Melety in the Annunciation Church in Harbin, which was the podvorye of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Peking, then under the direction of Archbishop Innokenty of Peking & China. The next day, the new Hieromonk Sophrony was elevated to Archimandrite. On 10 April 1922, in the Harbin St Nicholas Cathedral, Archimandrite Sophrony was consecrated to the Episcopate as Bishop of Selenginsk, Vicar of the Transbaikal Diocese, by the Hierarchs Mefody, Melety, Mikhail & Nestor. The sources state that this consecration was requested by Patriarch Tikhon, after ‘consultation’ with the clergy of the Transbaikal Diocese at the end of 1921, and that the new Bishop would administer the Diocese; the sources also mention the “Transbaikal Diocese” with “Far Eastern Metropolia” afterwards in parentheses. Since the Harbin Diocese had just been created by the Russian Church Abroad in Yugoslavia, it is not known why Bishop Sophrony is unmentioned in the annals of the Church Abroad. It seems that his tonsure in the podvorye of the Ecclesiastical Mission in China/Peking & China Diocese, and his consecration in the Cathedral of the Harbin Diocese, presided over by the ruling Bishop of the Harbin Diocese-representing both of the only ‘nearby’ entities recognizing the authority of the Church Abroad, certainly underscored that the new Bishop was also under its jurisdiction. Bishop Sophrony himself afterwards suffered a tortuous road: arrest for refusal to recognize the Renovationists, briefly succumbing to the Renovationists, repentance, arrest and imprisonment in Solovki, and exile in Siberia. In 1932 he was appointed as Bishop of Arzamas, Vicar of Nizhegorod by Metropolitan Sergey (Stragorodsky, +1943, later Patriarch), and died on the day of his arrival in Arzamas. [32]http://www.pstbi.ru/cgi-bin/db.exe/koi/m/?HYZ9EJxGHoxITYZCF2…WY+[33]http://drevo-info.ru/articles/20769.html[34]http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A1%D0%BE%D1%84%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B9_(%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2)[35]http://www.ortho-rus.ru/cgi-bin/ps_file.cgi?2_358

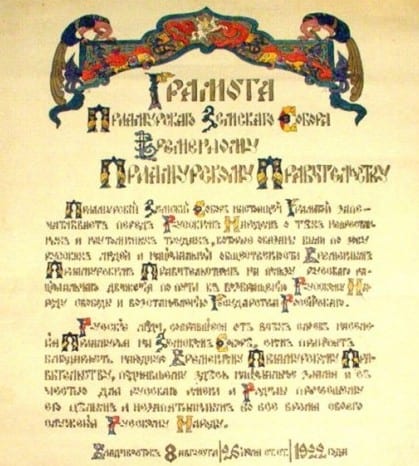

In 1918, General Dmitry Horvath, long head of the Chinese Eastern Railway, builder of the Trans-Siberian railways, Commissioner of the Provisional Government, and High Commissioner of the Government of the Russian Far East, had reluctantly agreed to the title of Provisional Supreme Ruler. He gathered a government, and also hosted the military delegations of the Allies present in Vladivostok: the Americans, English, French and Japanese. He stepped aside for the authority of Admiral Kolchak, and retired in 1920, leaving to live in Harbin, Manchuria. General Mikhail Dieterichs, a commander of Admiral Kolchak’s White Forces, also retired to Harbin in late 1920, but returned to Vladivostok in June 1922 to “create at least a fragment of a Russian State in the Far East, to continue the resistance of the Whites against the bolsheviks.” It was his ‘dream’ to convene a Zemsky Sobor, which was made reality on 22 June 1922. At the Zemsky Sobor, held in Nikolsk Ussuri, General Dieterichs was elected Ruler of the Land of the Amur, and Commander of the White forces. Bishop Mikhail participated in the Zemsky Sobor as Diocesan Bishop. Under the leadership of General Dieterichs, the Zemsky Sobor recognized that the sins of the Russian people had caused of the revolution, and further, called the people of Russia to repentance, rocignizing that the only salvation for Russia was the restoration of the Romanov Dynasty. The Sobor named the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich Romanov as the new Tsar, and Patriarch Tikhon was named as Honorary Chariman of the Sobor; neither the Patriarch nor the Grand Duke were present at the Sobor. The Sobor also restored the basic laws of the Russian Empire in the Amur region. General Dieterichs took the oath of office at the Dormition Cathedral, possibly administered by Bishop Mikhail as the ruling Bishop of the Diocese. Also taking part in the Zemsky Sobor was Bishop Sergey (Sergey Tikhomirov, ‘1863 or 1871’-1945, later Metropolitan) of Tokyo & Japan. It was also decided during the Zemsky Sobor that in October 1922, a Far Eastern Local Church Council would take place in Vladivostok, to create the Provisional Supreme Church Authority of the Far East. The approach of Bolshevik troops prohibited the Council from taking place. Civilian life and government offices had been restored in General Dieterichs domain, but this was a last gasp, and did not last long. The bolsheviks took Vladivostok in late October 1922, only two months after the conclusion of the Zemsky Sobor. [36]http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A5%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%82,_%D0%94%D0%BC%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%9B%D0%B5%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%87[37]http://d-m-vestnik.livejournal.com/387485.html[38]http://drevo-info.ru/articles/3528.html[39]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zemsky_Sobor

Bishop Mikhail left the Russian Far East with Bishop Sergey (Tikhomirov) for Japan. Bishop Mikhail lived at the Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Tokyo, headquarters of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Japan, with the blessing of Bishop Sergey, for the remainder of 1922, and part of 1923. While in Tokyo, Bishop Mikhail concelebrated with Bishop Sergey and Bishop Nestor (Anisimov) of Kamchatka (a friend of Bishop Sergey, who also lived in Japan at various times in the early 1920s) the episcopal consecration of the New Russian Hieromartyr Bishop Pavel (Vvedensky) of Nikolsk Ussuri, Vicar of the Vladivostok Diocese. As a priest, Bishop Pavel had served in both the Samara & Vladivostok Cathedrals, and was obviously well known to Bishop Mikhail. Bishp Pavel temporarily served as administrator of the Vladivostok Diocese, then served as Bishop of Melekessky, and Bugulma, both Vicariates of the Samara Diocese. He was interned in Solovki in 1924, and exiled to Ufa in 1927. He served as Bishop of Kaluga in 1927, of Orenburg in 1928. In 1931 he was a member of the summer session of the Holy Synod; the same year he was arrested again, and eventually retired in 1933. In 1935 he was appointed Bishop of Morshansk, and was shot there in 1937. [40]op. cit. 3[41]http://www.eparhia-tmb.ru/o-eparxii/istoriya/episkopy-morshanskie/

The great Kantos earthquake of September 1923, and the subsequent fires, destroyed the buildings of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Japan. Bishop Mikhail left Tokyo on 10 Oct 1923, and moved to Harbin. In Harbin, Bishop Mikhail participated in Church life, including participation in the efforts of all the hierarchs in the Diocese to suppress the attempts of renovationist clergy to gain a foothold. Bishop Mikhail reposed on 22 July 1925, and was buried under the arches of the St Sophia Cathedral in Harbin. [42]op. cit. 3[43]Bakonina, S. N. Kharbinskaya eparkhiya v period rasprostrananiya sovietskogo vliyaniya v Kitae (1923-1924) Vestnik PSTGU 2008 Bishop Mikhail was remembered as a spiritual writer of note, and had many articles published in the journal of the Kazan Diocese. [44]op. cit. 1

Other sources, however, dispute the repose of Bishop Mikhail in Harbin in 1925. The website of the Samara Diocese includes contradictory information: that Bishop Mikhail died in exile in Japan in the late 1920s, [45]http://samara.orthodoxy.ru/Istoriya/Svyatit.html and also, that ““Together with the retreating Cossack chieftain Dutov Bishop Michael was forced to leave Russia, and died in exile in 1928.” [46]http://samara.orthodoxy.ru/Istoriya/Istoriya.html Ataman Dutov left Russia in May 1920 with Ataman Annenkov, they went to China; Dutov was hunted in China by a nine man Cheka squad, and shot dead at point blank range in Suiding, China, on 7 Feb 1921, while Bishop Mikhail was still in Vladivostok, where he would live yet for more than a year. Dutov did not depart Russia from Vladivostok. [47]Wikipedia, “Dutov, Alexander Ilyich” While the Dutov ‘connection’ seems improbable, it does not reflect on the supposed date of Bishop Mikhail’s repose.

Yet another source states that Bishop Mikhail was alive at least until May 1926, when he supposedly participated in an episcopal consecration for the Albanian Orthodox Church in Montenegro. In 1922, there was a “People’s Church Council” in Berat, Albania. This Council proclaimed the Autocephaly of the Albanian Church, and elected Archimandrite Vissarion (Villard Dzhuvani) as the first Albanian Bishop. Archimandrite Vissarion had been educated at the Theological Faculty of Athens University, and, at the time of the Council, was serving in Sofia, Bulgaria. On 18 Sep 1922, the Albanian government recognized the decisions of the Berat Council. The Ecumenical Patriarchate vehemently protested the People’s Church Council, and especially its results. Due to back and forth protests, prohibitions, etc., it was not until May 1926, “with the tacit approval of Patriarch Dimitri of Serbia,” that Archimandrite Vissarion was consecrated to the episcopate by two Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Bishop Germogen (Maximov, 1861-1945, who later went on to head the Croatian Orthodox Church of the WWII era) and … Bishop Mikhail (Bogdanov) “of Samara,” in a Serbian Orthodox Monastery in Montenegro. [48]http://www.pravoslavie.ru/smi/1390.htm

Since Bishop Mikhail had protested against the creation of the Harbin Diocese as infringing upon his Diocese of Vladivostok, it seems unlikely that he would identify himself, 8 years after leaving Samara, and still carrying the title ‘of Vladivostok,’ as Bishop ‘of Samara.’ The fact that numerous Hierarchs resided in Harbin, that the Diocese published Church periodicals, and certainly would have been strictly accurate in keeping records, especially in the case of the repose, funeral, and burial of a hierarch, taken together, seems to all work against a date of repose other than 22 July 1925 for Bishop Mikhail. No matter the date-Memory Eternal!

- http://srn-fareast.ucoz.ru/publ/23_ijulja_1922_goda_vo_vladivostoke_otkrylsja_priamurskij_zemskij_sobor/3-1-0-136

- http://d-m-vestnik.livejournal.com/367206.html

References

“Архимандрит Михаил в миру носил имя Михаила Александровича Богданова и происходил из семьи священника. По окончании Казанской духовной академии он остался в Казани, где начинал псаломщиком, получив спустя три года сан священника. Дальнейшие события говорят о том, что Михаил выбрал путь служения Богу, так как в 1902 году он принимает монашеский постриг, а в 1905 году его назначают ректором Казанской семинарии. Тогда же он становится архимандритом. Владыка умер в Харбине, покинув Россию осенью 1922 года.

Судьбе было угодно, чтобы знакомство Распутина с архимандритами Михаилом (Богдановым) и Хрисанфом (Щетковским) произошло в нужное время, и Распутин, вдохновленный казанскими священниками, отправился покорять столицу.”

https://lib.rus.ec/b/613964/read