From Editor

This paper was written for the graduate class ROCOR History and Identity-723 offered at Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary at the fall of 2019. The Russian Orthodox presence in North America began in the 18th century with colonization of Alaska. In the last fifteen years of the 19th century after the mass conversion of Greek-Catholic immigrants from Austro-Hungarian Empire the Russian Church has firmly established itself in “lower forty-eight.” The St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox community in Mayfield, PA has been playing an important showcase role from the very beginning of the Russian Orthodox presence in the continental states. In 1907 the First All-American Sobor took place there. The failure to incorporate Russian Mission at this council reflected mistrust of the strong hierarchical authority on behalf of the former uniates, [1]In writing this introduction I am heavily indebted to the following research: E.R. Lanier, Church Lands Polity in Historical and Legal Evolution: the Genesis of the 2002 Property Lien Resolution … Continue reading whose former Greek-Catholic parishes were established as congregational. 10 years later the Mission was registered as corporation in New York and Pennsylvania. In 1918 these corporations in the two mentioned states adopted their parish by-laws. This legalization became a crucial issue in these years following the Russian revolution when “the acting” Archbishop Alexander (Nemelovsky) had to bail out the Mission from the debts by selling its proprieties. At the same time the Mission’s right to owe proprieties was legally challenged through a suit initiated by its suspended priest Fr. John Kedrovskii. In 1924 at the Fourth All-American Sobor in Detroit the mission was organized as an metropolitanate under the title “the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of North America.” [2] The Statute of the Orthodox Church in America (2015). The Orthodox Church in America. https://www.oca.org/files/PDF/official/2018-0724-oca-statute-final.pdf (accessed on June 19, 2020). The Normal Statues of Metropolia adopted in 1935 did not object of parishes’ right to hold properties in their name. The 1955 statute revoked this right requiring parishes to incorporate themselves legally into Metropolia’s corporation. To sum up what I have written above I am using a conclusion made by the ROCOR Hegumen Photius (Ulanov): “Thus Orthodox religious organizations because of their corporative status function simultaneously according to both canon law of the Orthodox Church and civil laws of the United States.” [3] Dr. Alexey N. Ulanov, Fiansovo-pravovi status religioznoi organizatsii v pravovoi sisteme SShA (Moscow: URSS, 2016), 69. Such is a very broad background to Fr. Daniel’s paper. It demonstrates how American religious context is different from the one in the old world, where history and geographical location heavily contributed in support of the hierarchical order. This paper is also a witness to another specific of the American Orthodox context when churches theoretically hierarchical in practical are congregational.

Deacon Andrei Psarev,

June 19, 2020

Introduction

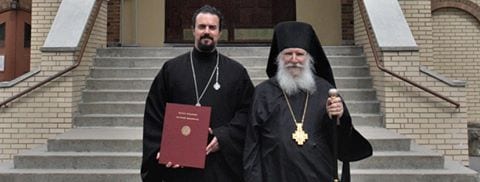

The Rector of Holy Trinity Seminary Bishop Luke of Syracuse with the first graduate of M.Div program Fr. Daniel Franzen

After being ordained to the priesthood in 2017, I had the great honor and privilege of serving the faithful of St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Mayfield, PA for 18 months. Under the guidance, mentorship and friendship of Mitered Archpriest John Sorochka, I grew to know and love the (largely) Carpatho-Russian Americans that live, work, and pray in this northeastern Pennsylvania town as well as the physical temple itself (which reflects the heritage of those who built it).

While attached to the parish, and little by little, I gained a working knowledge of the parish’s unique history and personalities. One aspect of the history of the Mayfield parish which still lives in the memory of many parishioners is the 1980s legal battle with the Orthodox Church in America (OCA). [4]Formerly the North American Metropolia and distinct from the Russian Church Abroad (ROCOR). From the beginning of ROCOR’s existence and until 1926 Metropolia was part of ROCOR then Metropolia … Continue reading

Though the Mayfield parish stands out for its lengthy litigious battle with the OCA and its eventual success in the courtroom (allowing it to leave the OCA and move into the ROCOR), there were other parish legal battles between the Metropolia/OCA and ROCOR in the 20th century. [5]On the separate level there are litigations between ROCOR and splinter groups like the challenge to ROCOR to remain in control of the Resurrection parish in Worcester, which was founded by Russian … Continue reading Of note are the Holy Transfiguration Parish in Los Angeles, CA in 1949 (lost by Metropolia), Kazan Icon of Mother of God in Sea Cliff, NY in 1971 (lost by ROCOR) and in 2000 the St. Mary of Egypt Parish in Norcross, GA (lost by ROCOR). [6] The Los Angeles case was settled in favor of the ROCOR while the Norcross, GA case was won by the OCA for reasons which will be discussed briefly below. The less known is the very first court case between two church against St. Nicholas Church in Elizabeth, NJ in 1931 (lost by ROCOR) and the second of the same year for All Saints parish in Hartford, CT (ROCOR won). [7] Lanier, Church Lands Polity, 162, 169-170.

Part of the consciousness of countless members of the Mayfield parish is the fact that their ancestors paid for and built the temple by themselves. That is, there was no outside monetary aid – it was the blood, sweat, tears of hard-working, immigrant, coal mining families that made that parish what it is. Furthermore, though they (the people) came into Orthodoxy in 1902 (under the future St. Tikhon of Moscow, 1865-1925) from Greek-Catholic Church, they never saw themselves as anything but Orthodox. That is, they were simply and piously following what had been handed down to them from their forefathers (who likely became Uniates in the 17th century in the Old World).

The research question of this paper is that the legal and functional (in some sense, at any rate) congregationalism of the Mayfield parish enabled it to emerge victorious in its legal battle with the OCA in the 1980s.

In order to understand the events surrounding the lengthy lawsuit filed by the OCA against the Mayfield parish in 1982, I will first outline the nature of American Orthodox congregationalist ecclesiology and the historical realities of parish life at the beginning of the 20th century. I will then explain the mechanisms that were put in place at the beginning of the 20th century by the founders of the parish which enabled them to provide a strong legal case against the OCA. Essentially, because the Mayfield parish (and dozens of others like it) had been set up and operated as an independent, self-sufficient entity, it was able to retain its property and assets when it was faced with a hierarchy/diocese that sought to impose contrary practices on it (in this case, it was the so-called “Revised Julian liturgical Calendar”).

This paper does not seek to open old wounds that have been healed (for the most part) between the OCA and the ROCOR concerning the Mayfield parish, even though this event is still remembered and was directly experienced by many current clergy and laity in the northeastern Pennsylvania region. Though the OCA and the ROCOR had unpleasant and polemical encounters in the 20th century, this paper does not seek to address any of them or take sides. Rather, I am going to look at the Mayfield case as an example of the phenomenon known as “American Orthodox Congregationalism.”

The Origins and Character of American Orthodox Congregationalism

The research question of this paper is that the legal and functional (in some sense, at any rate) congregationalism of the Mayfield parish enabled it to emerge victorious in its legal battle with the OCA in the 1980s. The matter of American Orthodox congregationalism is itself an interesting subject and was the focus of the 2003 doctoral dissertation of Nicholas Ferencz. The contention of Ferencz is that “American Orthodoxy lives out an experience of church which is at odds with its professed understanding of church.” [8] Nicholas Ferencz, American Orthodoxy and Parish Congregationalism, (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006), 2. Ferencz defended his dissertation at Duquesne University.

Why this is important is that the Orthodox Church is a hierarchical Church. That is, its historical existence runs contrary to the congregationalist model which characterizes Protestantism, Islam and Judaism. “This is, then, the anomaly presented: congregationalism in a hierarchical-synodal church. Congregationalism, often called trusteeism, can be defined here as the idea that the authority of the church resides totally within the lay congregation of each parish community.” [9] Ibid.

According to Helen Rose Ebaugh’s sociological study of congregationalism, it has five criteria:

1) a formal list of members;

2) an elected, local governing body;

3) lay societies and ministries;

4) home-grown clergy; and

5) raises its own money and functions without outside assistance. Congregationalism is also marked by lay (i.e., local) control over the material goods of the parish and the property. [10] Ibid, 3.

Ferencz, almost anticipating the exact scenario that arose in Mayfield in 1982 said that in an ecclesiastical situation where the theoretical ethos of the authority was hierarchical, as in Orthodoxy where there is top down control, and yet the actual authority structure operated differently as in congregationalism: “it is reasonable to predict that the function and goals of that authority will be thwarted. It may even be possible to predict in what ways parish life will go awry.” [11] Ibid, 7.

Following Ferencz, it is helpful to categorize Orthodox ecclesiology in two ways. First, there is what Ferencz calls “universal” ecclesiology. This model “emphasizes the communion of all bishops of the church as being the manifestation of the oneness and catholicity of the Body of Christ.” [12] Ibid, 18. The Ecumenical Councils and the gathering of all the bishops from various parts of the world to decide important theological and disciplinary matters may be considered as representative of this model. It is important to note that what is stressed here is the “unity of the clergy and faithful people with their bishop, from whom all authority derives by virtue of his office.” [13] Ibid, 20. The universal model is supported by several Church canons such as Apostolic Canons 38, 39, and 41. [14]Canon 41 is noteworthy in that it explicitly ascribes authority over the parish property to the bishop. The theory is that if the souls of the flock are entrusted to him (and souls are much more … Continue reading

The second model may be called “eucharistic” ecclesiology. This model “finds the unity and catholicity of the church primarily in the assembly in one place or locale…” [15] Ibid. Certainly, these two models are not mutually exclusive, but it is helpful to note that parish congregationalism more readily lends itself to the eucharistic model. Ferencz notes rightly that the eucharistic/local model prevailed in the post-apostolic and pre-Constantinian era, whereas the universal model prevailed afterward.

It is interesting that in America, a thoroughly non-Orthodox and non-hierarchical country, Orthodox “practical” ecclesiology developed along eucharistic/local lines rather than along universal ones. As this relates to the Mayfield parish, it should be remembered that the local people built, maintained, and ran the Orthodox Church there without financial assistance or administrative guidance from any official hierarchy. Certainly, their ecclesiastical loyalty and connection with the Russian Church and its bishops (in particular, the future St. Tikhon of Moscow) was real. However, there was never any question who owned and operated the parish – the people.

The unique development of Orthodox ecclesiology in America has created a situation that is truly unprecedented. Ferencz notes that “there is no place in the tradition of the church for the exercise of any authority apart from the church as a whole and independent of the authority of the Body of Christ.” [16] Ibid, 70. This being the case, there is “no sense ever of a ‘spiritual authority’ being given to the clergy which is apart from a ‘material authority’ given to the laity.” [17] Ibid, 71. All authority in the Church derives from Christ and requires all the members of the Body of Christ – in their proper roles – to faithfully administer that authority. Ideally then, this includes the bishop, whose role it is to have spiritual and material authority over the parishes in his diocese.

Orthodox congregationalism is certainly the norm in America, but why? And why has it prevailed to this day? Ferencz notes that this state of affairs has not been questioned for two reasons. One, “in many places such beginnings are almost within living memory.” [18] Ibid, 74. Mayfield is an excellent example of this phenomenon. Many of the current members’ recent ancestors built the parish and their sense of ownership of the same is palpable. Two, “few have ever really questioned the manner in which the parishes started…since most laity and many clergy regarded this congregationalist establishment as normal or natural,” no one doubted the legitimacy of their origins. [19] Ibid. And why should they? The everyday parishioner, whose father or grandfather built the parish building (often a beautiful, ornate, and large one at that) and whose mother or grandmother tirelessly assisted with fundraising projects (such as bake sales), Yolkas, the sisterhood, etc., and whose bishop made regular visits, would likely have no reason to question the normality of their parish life. Many early American parishes such as Mayfield had thriving communities with dozens of baptisms, marriages, and events each year.

Orthodox congregationalism is certainly the norm in America, but why? And why has it prevailed to this day?

A greater understanding of how Orthodox parishes and jurisdictions function (then and now) in America is still needed in order to deepen one’s understanding of the contemporary situation and (later) the Mayfield court case. Ferencz discusses the three levels of authority present in each American Orthodox jurisdiction. [20]Time and space preclude a fuller discussion of the jurisdictional situation in America. Far from the standard, historic, geographical model of jurisdiction, Orthodox jurisdictions such as the OCA, … Continue reading

First, there is the authority of the canons of the Church (such as the ones previously mentioned). These canons – especially those promulgated at an Ecumenical Council – ideally carry a significance unlike that of individual bishops or clergy (and their judgments) at the diocesan or parish levels. Without detailing the nature of the divine authority imbued in the canons, there is at least a basic assumption of their authority which transcends one’s particular time and place.

Second, there is the authority of the hierarchy at the diocesan level. At this level, the authority functions according to a top-down model where the bishops truly preside and decide jurisdictional/diocesan matters as one might expect. And third, there is the authority of the clergy and laity at the parish level. Ferencz notes that at the parish level, the authority is often split into “spiritual” and “material” spheres with the “pastor and hierarchy maintaining authority over ‘spiritual’ matters, while the lay congregation enjoys virtually sole authority over all ‘material’ matters affecting the parish.” [21]Ibid, 81. This is not an explicitly prescribed policy in either the OCA parish bylaws (Article XII of The Statute of the Orthodox Church in America) or the ROCOR parish bylaws (Part IV). It is … Continue reading

As it pertains to the Mayfield parish and their decision to leave the OCA, there was then a level of ambiguity in the OCA parish by-laws regarding property ownership and use that has since been clarified in The Statute of the Orthodox Church in America. Currently, the statute states that the “Parish corporation holds legal title to all Parish property, assets, and funds.” [22] https://www.oca.org/statute/article-xii. (Accessed on 12/20/19). Nevertheless, the property is “held by the Parish or Parish corporation in trust for the use, purpose, and benefit of the Diocese of The Orthodox Church in America of which it is a part.” [23] Ibid. Furthermore, if the parish “attempt[s] to disaffiliate from The Orthodox Church in America in a disorderly manner, all Parish property, assets and funds of such Diocese are and shall remain subject to the use, purpose, and benefit of The Orthodox Church in America.” [24] Ibid. This later verbiage is what effectively allowed the OCA to be victorious in its lawsuit with the Norcross, GA parish in 2000. [25]https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ga-court-of-appeals/1060354.html (Accessed 12/20/2019). The court specifically noted that though the parish legally owned the property, the bylaws effectively nullified … Continue reading

The tension here is obvious: the parish legally owns the property, building, assets, etc., but agrees (by dint of its acceptance of The Statute) to give it up to the diocese were a “disorderly” disassociation were to occur. One can hardly expect there to be an orderly resolution to the situation described in this section. In 1982, when the Mayfield parish was attempting to leave the OCA (over the imposition of the “Revised Julian Calendar”), the stipulation regarding the penalty for leaving the OCA had not been a part of the operating bylaws of the parish. In fact, the parish was officially operating on the 1962 bylaws which stated that the parish property was not transferable without a majority vote of the parish. [26]This was noted in the March 1, 1988 PA Supreme Court ruling to deny the OCA’s appeal of the previously unfavorable (to the OCA) court ruling in favor of the Mayfield parish. The documents … Continue reading In other words, the Mayfield parish was not operating on official OCA bylaws at the time of the legal dispute.

The ambiguous arrangement found in the both the OCA and ROCOR bylaws is quite different in, say, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese. In this jurisdiction, the event of “‘heresy, schism or defection from the Archdiocese’ the Special Regulations provide in the strongest language that the Archbishop has the power to take over the parish completely, including control of its properties.” [27] Quoted in Ferencz, American Orthodoxy and Parish Congregationalism, 103. The relevant section is GOASR II.1.XVII.1.

The ambiguous arrangement found in the both the OCA and ROCOR bylaws is quite different in, say, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese.

Ferencz notes that there are “three proximate causes” for American Orthodox divergence from traditional Orthodox hierarchical authority. First, there is what he calls the “moral absence” of the bishops. Second, the “Toth schism and its aftermath”, and third, the “presence of lay societies as models for trusteeism.” [28]Ibid, 114. The Mayfield parish was certainly affected by the actions of St. Alexis Toth and his spearheading of a mass exodus from Greek-Catholicism to Russian Orthodoxy. The Mayfield parish … Continue reading What Ferencz calls the “moral absence” refers not to an “ethical absence” as one might be led to believe by the use of the term “moral.” Rather, what he means by “moral absence” is a “practical absence” of the hierarchy owing to the fact that most parishes “were founded with little to no input from Orthodox hierarchy.” [29] Ibid.

In other words, most parishes were (especially at the beginning of the 20th century) founded by laymen and through “grassroots” type efforts from immigrants who were not concerned about bishops and their guidance but about things such as where and how they were going to bury their dead, baptize their children, and marry their sons and daughters.

In locales such as northeastern Pennsylvania, the immigrants who established these parishes were not missionaries but simple, hard-working coal miners. This non-missionary character remains to this day. This is not to say that these parishes are not welcoming to inquirers or concerned about the souls of the non-Orthodox. It is simply to say that the parish’s needs and personalities shaped the character more than any association with a particular bishop or jurisdiction and their dictates or missionary programs. [30]The Russian mission to Alaska would represent the “missionary” minded establishment of Orthodoxy. A well-trained clergy, with orders and procedures from its hierarchs, went to a foreign land and … Continue reading Ferencz goes on to note “even if the hierarchy wanted to change this mode, it was pastorally very difficult if not impossible.” [31] Ibid. The first Orthodox parishes in America just were founded in a congregationalist manner.

From the very beginning, Orthodox parishes were owned by congregations, as such, and not a diocese, jurisdiction, or hierarchy. Ferencz notes that Toth himself attempted to influence parishes to place their properties under the bishop/diocese in order to be consistent with traditional Orthodox practice. Toth actually placed the deed of the Wilkes-Barre parish (33 miles south of Mayfield) “in the bishop’s name in 1893.” [32] Ibid, 121.

Woven into the fabric of local parishes’ (particularly those constructed by former Uniates) resistance to diocesan ownership of properties was a distrust of the hierarchy. Having had centuries of tumultuous relationships with Roman Catholic bishops and following the recent mass exodus into Orthodoxy under Toth, many parishes simply could do without the headache of antagonistic relations with their new hierarchs, the Russian bishops. This attitude ensured that the newly Orthodox retained their parishes; “by keeping control of the property, even if they lost control of pastoral assignments, parishes retained the leverage necessary to prevent unwanted changes in their way of doing things.” [33] Ibid, 164.

Now that the American Orthodox situation has been briefly described, the Mayfield case should be more easily understood. Something not yet addressed, but which importance is extraordinary, is the American legal system and the principles they use to adjudicate such matters. As the reader will see, these principles played an enormous role in Mayfield’s success in retaining control of their parish.

The Case of Mayfield

Owing to the massive amount of documentation accompanying the Mayfield court case from the 1980s, this section can only be a brief summary. [34]On 10/28/19 I received several hundred pages of Lackawanna County Court Documents (Various) in the case of Orthodox Church in America… Plaintiffs vs. Thomas Pavuk, Andrew Paserp, Rose Telep, John … Continue reading Therefore, the arguments of the plaintiffs (the OCA) and defendants will be summarized and will be followed by a synopsis of the final ruling.

The (Plaintiff) OCA’s Argument

The argument of the OCA is relatively simple and can be stated under two-component arguments. First, owing to the hierarchical nature of Orthodoxy (and the Mayfield parish’s subordination in 1951 to the then Metropolia), the parish was not legally or ecclesiastically permitted to function in a congregational manner. This would obviously preclude the very important August 22, 1982 all-parish vote where they decided to leave the OCA and petition the ROCOR for (re)entry. [35]This is a touchy subject and a legally significant one. One of the Mayfield arguments against the OCA was that they were initially under the ROCOR (they certainly were from 1935-1946 when the … Continue reading In fact, the plaintiffs called this meeting an “illegal act and of no effect.” [36]From the “History of the Case” portion of the 1986 “Plaintiffs’ Brief in Support of Motion for Post-Trial Relief,” p. 33. The Plaintiffs filed their lawsuit with Lackawanna County on … Continue reading

The second component of the plaintiffs’ argument was that they (the OCA) were/are the rightful and legitimate successor of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church (under whose name the Mayfield parish was founded in 1902 and incorporated in 1907), the Patriarchal Russian Orthodox Church (reestablished in 1917), and under whose authority it (the Metropolia) received “autonomous” status in 1924. Further, this “autonomous” existence was elevated to “autocephaly” in 1970, granting the OCA the canonical authority over North America. [37]While this narrative is both tidy and legally valid, it is far from being accepted as the actual state of affairs by the other local Orthodox Churches. It was also not enough to convince the court … Continue reading

Regarding the first point, the OCA cited an older case wherein a similar scenario (not detailed in the document) the court ruled in favor of the hierarchical authorities where there was a dispute between the hierarchy and the people. The court stated that “constitutional protection of hierarchical organizations precludes not only legislative and judicial action which would destroy church government, but also action by church members themselves which effects a transfer of Church property form the control of one hierarchy into the hands of a competing hierarchy.” [38] “History of the Case,” p. 38.

This is a strong argument and it is sort of the culmination of the plaintiffs’ case. But the argument is a species of special pleading. If this principle was upheld in every scenario, the Russian Mission (Metropolia) would never have acquired the dozens (if not hundreds) of former Uniate parishes following the Toth exodus. Given the relative proximity to that truly monumental event, one would think there would have been more caution exercised by the OCA in using it. Nevertheless, in the American legal system, as in the Byzantine canon law, precedence can and does have significance.

An interesting aspect of the OCA’s case that should be noted is the conspicuous absence of any notable activity from 1907 to 1951 regarding the jurisdictional changes of the Metropolia. In other words, it appears (the reader is reminded here that this is the OCA’s own brief and as such represents their best legal argumentation) as if the OCA deliberately left out the ROCOR’s claims of authority after the 1920 Ukase No. 362, [39]Later in the brief, the OCA noted the 1922 Ukase of Patriarch Tikhon which instructed the ROCOR’s supreme authority to disband. On the decree no 362 see Archpirest Nicholas Artemoff, “The Local … Continue reading the chaotic decades of the 1920s and 30s, the return of the Metropolia to the ROCOR from 1935-1946, and the fact that in 1951, the parish of Mayfield voted to affiliate with the Metropolia, thus indicating that they were not then under their authority.

One of the weaknesses of the legal case against the Mayfield parish was the admitted ambiguity of the 1951 arrangement with the Metropolia. Both the plaintiffs and the defendants noted that when the parish agreed to affiliate with the Metropolia, the OCA made no effort to alter the congregationalist bylaws of the parish. Apparently – and this is reported by both sides – Metropolitan Leonty (the first hierarch of the Metropolia at the time) said that the details of the arrangement could be “worked out” at a later date. [40] “History of the Case,” p. 5.

Regarding the second component of the argument (the question of who is the rightful successor of the Russian Church in America), the plaintiffs brought in the priest of the OCA, professional theologian and Byzantinist, Dr. John Meyendorff. In their effort to prove that the OCA was the legitimate heir of the Russian Church (thus proving that, under hierarchical circumstances, the Mayfield parish had no right to leave), Meyendorff relied on the 1922 ukase of Patriarch Tikhon which “dissolved that church administration.” [41] Ibid, 14. The conclusion of this line of argumentation is that the ROCOR should not have actually existed after 1922. Therefore, at best, the ROCOR, whose canonical legitimacy was defended by then Bishop Mark of Berlin and Germany (Dr. Arndt) could claim independence from – on spiritual and political grounds – the Russian Church, but not claim to be its rightful successor. [42] Ibid, 19.

The Mayfield Parish Argument

As previously mentioned, the Mayfield parish left Uniatism for Russian Orthodoxy in 1902. When they did this, they specified to the Russian bishop four requirements. One of those requirements was that all “the deeded property must be in the possession of the parishioners, that it not be transferred either to the bishop or to any other person…” [43] “Defendants’ Brief in Support of Continued Control of Church Property by Local Parish,” p. 3. The bishop wrote back and agreed to the terms [44]Of particular note was the third term put forward by the Mayfield parish which stipulated that they did not have to repudiate or deny any “Unia” as they had always considered themselves Russian … Continue reading and did not require any transfer of property.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution, and according to Church records (also entered into evidence on behalf of the defendants), the most significant events in the Mayfield parish – such as the 1933 consecration of the new temple – were officiated by ROCOR bishops. In the case of the consecration, the document was signed by Bishop Adam “under the authority of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, the Synod in Karlovci and its president, His Eminence Metropolitan Anthony.” [45] “Defendants’ Brief…” p. 10.

The brief goes on to mention the famous Ukase 362, Fr. Meyendorff’s testimony, Archbishop Mark’s testimony, as well as a well-known local case involving a similar dispute between Orthodox hierarchies. Of note is the admission of Meyendorff that the OCA was considered a schismatic group by the Moscow Patriarchate from 1931-1970. [46] Ibid, 11. When the Mayfield parish affiliated with the OCA in 1951, it specifically stated that “the Parish accepts Metropolitan Leonty as its spiritual head and leader, but that his power, authority [sic] does not extend over, encompass the movable and immovable properties such as parish buildings…” [47] Ibid, 14. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7. Quite ironic. Furthermore, Bishop Herman, in his testimony, admitted that “nowhere did the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church in America ever express in writing that Church property would be controlled, or even placed in trust…” [48] Ibid, 15.

The defendants relied heavily on what is known as the “neutral principles of law” in order to show that their legal ownership cannot be challenged by “denominational” authorities. They cited the Presbytery of Beaver-Butler of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States, et al. v. Middlesex Presbyterian Church, et al. 1985 case in order to claim First Amendment justification of their cause. On this logic, the secular courts had no right to judge a case based on doctrinal, theological disputes (the basis of the OCA’s case). Further, they could only judge these types of cases based on the legal documentation attending the dispute.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania stated that courts must “decide church property disputes without resolving underlying controversies over religious doctrine.” [49] Quoted in ibid, 18. The defendants (the Mayfield parish) go on to dispute the claims of the OCA as the rightful successor of the Russian Church in America anyway and invoked what it deemed to be inconsistencies in Fr. Meyendorff’’s testimony. One important inconsistency in the OCA narrative invoked by Fr. Meyendorff was/is the presence of Moscow Patriarchate parishes within the canonical boundries of the autocephalous OCA. Since the agreement of autocephaly only gave the OCA jurisdiction over those clerics and parishes that were currently in the Metropolia and not the MP parishes, the OCA could at best be seen, alongside the ROCOR, as a “branch” of the Russian Church, rather than its successor. [50]Ibid, 20-21. Meyendorff further admitted that Ukase 362 was the OCA’s canonical basis for legitimacy prior to 1970. This is an astounding admission, especially considering that Meyendorff … Continue reading

A part of the legal, as opposed to the doctrinal, case made by the Mayfield parish is the fact that the (then) current bylaws of the parish were the 1962 bylaws which stated that the property “shall duly remain the sole property of said congregation and church and under no circumstances shall be transferred to any Bishop…without approval of a majority vote of a parish meeting.” [51] 1962 bylaws quoted in ibid, 22. In other words, the Mayfield parish basically doubled down on the notion that they were, functionally speaking, a congregationalist structured parish. This is, in fact, what the Mayfield parish legal brief was arguing.

Not only did the 1962 by-laws state that the property could not be transferred barring a majority vote, they also stated that the parish is able to “select its own hierarch by selecting its bishop.” [52] Ibid, 23. The legal brief went on to note that the Mayfield parish, far from being beholden to the hierarchy of the OCA, did not even legally recognize it until it democratically chose to affiliate with it in 1951. “This principle of free will, democracy and voting, is important to these families descending from Russian immigrants, and the concept of democracy is crucial to the fabric of American life.” [53] Ibid, 24.

A key legal precedent regarding parish/lay control of a property (over against a hierarchy-controlled model) was established in the case of St. Michael the Archangel Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church vs. Uhniat, 436 Pa. 222 (1969). In this case, the Metropolia had been the ruling hierarchy from 1955 to 1969. Even so, the judge (named in the brief: Justice Egan) ruled that since the parish [54] St. Michael’s Church located at 335 Fairmount Ave., Philadelphia, PA. was started under the Patriarchate of Moscow, the “proper religious group for St. Michael’s Church and its real estate was the Patriarchate.” [55] Ibid, 26. What this meant for the Mayfield case is that since the defendants had proved that their founding charter and temple consecration was under the ROCOR, the OCA (as in the St. Michael’s case) had no grounds to claim the property.

In their rebuttal argument to the OCA’s claim that as a hierarchical church, there was a sort of implicit agreement (trust) whereby the spiritual headship of the hierarchy translates into a material/financial headship, the Mayfield attorneys argued precedence in the case of Presbytery of Beaver-Butler of the United Presbyterian Church in the United States vs. Middlesex Presbyterian Church. They claimed that (as in the case just mentioned) a trust “must be created by clear and unambiguous language or conduct, it cannot arise from loose statements [such as things will be “worked out” later] admitting possible inferences consistent with other relationships.” [56] Quoted in ibid, 27. This is, then, is another legally consistent and established precedent used by the Mayfield parish in their defense.

At the same time in December of 1982, Judge Munley of the same Lackawanna County made decision against the ROCOR and in favor of the OCA arguing that St. Basil’s Russian Orthodox Church of Simpson, PA was hierarchical and not congregational. [57] Lanier, Church Land Polity, 354. However in 1985 this case was reversed in the favor of the ROCOR based on the described above “neutral principles of law” on internal church matters adopted in the same year in Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

In the final judgment, the Pennsylvania Court of Lackawanna County ruled in favor of the defendant, St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Church of Mayfield, PA. This was in large part due to the weight that the court gave to the “neutral principles of law” principle, the legal reasoning behind it, and the precedent of other denominational disputes. The strongest argument of the plaintiff OCA was their appeal to the hierarchical nature of Orthodoxy and the clear affiliation of the Mayfield parish with the OCA from 1951 to the time the dispute began (1982). Orthodox canon law further supports the OCA’s claim by its injunction that bishops (or synods of bishops) own parish properties and material goods thereon. This is certainly a valid argument and, perhaps under other circumstances, may have proved decisive.

The OCA’s argument, based on the testimony of Fr John Meyendorff, while compelling from a doctrinal and canonical perspective, was ultimately inconsequential in the court’s mind. Among other reasons, Fr. Meyendorff (in cross-examination) admitted that the OCA used to be in the same position vis a vis the Moscow Patriarchate as was the ROCOR. This meant that their claim to be the rightful successor of the Russian Church in America (then the hierarchy of the Mayfield parish at its return to Orthodoxy in 1902 and its incorporation in 1907) was effectively nullified.

Because of the strong language of the (in use) 1962 parish by-laws, the ambiguous wording of the 1951 affiliation with Metropolitan Leonty and the Metropolia, the legal precedents set in the two noted cases (St. Michael’s, and the Presbytery of Beaver-Butler), and the Pennsylvania court’s policy of a “neutral principles of law” approach all enabled the Mayfield parish to emerge victorious from this lengthy legal battle.

At the beginning of this paper, and with the help of Fr. Nicholas Ferencz, we saw how the ecclesiology of American Orthodox developed along local, even democratic, lines rather than hierarchical and canonical. This was in large part because of the unprecedented nature of Orthodox immigration to America beginning at the end of the 19th century and the relatively short history of this country. No jurisdiction has avoided this situation entirely.

It may be many more decades, if ever before traditional, canonical Orthodox life takes shape in this land. Even leaving aside the unprecedented nature of demographic overlap since the beginning, the American ethos lends itself to a local, democratic posture that is skeptical of hierarchy and absolute authority. The Orthodox jurisdictions in America have the choice of continuing along these democratic lines or they may begin to enact the more rigid, hierarchical model that is consistent with historical and canonical norms. Personally, I hope that the latter course of action gains some traction in the coming decades. That being said, if it were not for the former (local and democratic) model, I would never have gotten to know and grown to love the lovely people, temple, and clergy at the Mayfield parish. And for that, I thank God.

References

| ↵1 | In writing this introduction I am heavily indebted to the following research: E.R. Lanier, Church Lands Polity in Historical and Legal Evolution: the Genesis of the 2002 Property Lien Resolution (M.A.Thesis: Balamand University, Antiochian House of Studies, Legioner, PA, 2016), 58. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | The Statute of the Orthodox Church in America (2015). The Orthodox Church in America. https://www.oca.org/files/PDF/official/2018-0724-oca-statute-final.pdf (accessed on June 19, 2020). |

| ↵3 | Dr. Alexey N. Ulanov, Fiansovo-pravovi status religioznoi organizatsii v pravovoi sisteme SShA (Moscow: URSS, 2016), 69. |

| ↵4 | Formerly the North American Metropolia and distinct from the Russian Church Abroad (ROCOR). From the beginning of ROCOR’s existence and until 1926 Metropolia was part of ROCOR then Metropolia rejoined its again from 1935 and until 1946. In 1970 Metropolia received autocephaly status from the Church of Russia. On the early stage of relations see: Nikolaj Kostur, The Relationship between The Russian Orthodox Church in North America and The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad from 1920-1950 (M.Th. Thesis: SVOTS, 2009). |

| ↵5 | On the separate level there are litigations between ROCOR and splinter groups like the challenge to ROCOR to remain in control of the Resurrection parish in Worcester, which was founded by Russian emigres, but left ROCOR for the Holy Orthodox Church in North America. ROCOR lost this case since this parish was “hierarchical in matters of faith and polity, [Holy Resurrection] parish was congregational in terms of property ownership.” The quote for the 1993 court decision is cited from Lanier, Church Lands Polity, 309. In 2004, a settlement was made between the ROCOR diocese of Western America and the convent of the Vladimir Mother of God separated from the ROCOR (Jeannie Gore, “Russian nuns to keep convent for seven years,” Half Moon Bay Review (May 5, 2004). https://www.hmbreview.com/news/russian-nuns-to-keep-convent-for-seven-years/article_867538dc-f1dc-57cb-85ca-ae7ae892b2e1.html (accessed on June 19, 2020). There is also a perspective of other similar church trials with those communities who separated from ROCOR after the unification in 2007. |

| ↵6 | The Los Angeles case was settled in favor of the ROCOR while the Norcross, GA case was won by the OCA for reasons which will be discussed briefly below. |

| ↵7 | Lanier, Church Lands Polity, 162, 169-170. |

| ↵8 | Nicholas Ferencz, American Orthodoxy and Parish Congregationalism, (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006), 2. Ferencz defended his dissertation at Duquesne University. |

| ↵9 | Ibid. |

| ↵10 | Ibid, 3. |

| ↵11 | Ibid, 7. |

| ↵12 | Ibid, 18. |

| ↵13 | Ibid, 20. |

| ↵14 | Canon 41 is noteworthy in that it explicitly ascribes authority over the parish property to the bishop. The theory is that if the souls of the flock are entrusted to him (and souls are much more valuable than bricks or gold), why shouldn’t the physical property be entrusted to him as well? |

| ↵15 | Ibid. |

| ↵16 | Ibid, 70. |

| ↵17 | Ibid, 71. |

| ↵18 | Ibid, 74. Mayfield is an excellent example of this phenomenon. Many of the current members’ recent ancestors built the parish and their sense of ownership of the same is palpable. |

| ↵19 | Ibid. |

| ↵20 | Time and space preclude a fuller discussion of the jurisdictional situation in America. Far from the standard, historic, geographical model of jurisdiction, Orthodox jurisdictions such as the OCA, ROCOR, or the GOA (e.g.) function as vicariates of ethnic or “denominational” hierarchies which are still based in the “old world.” The exception is the OCA which was granted autocephaly in 1970 and therefore no longer has formal ties to Moscow. Nevertheless, in America, the OCA functions in the same manner as the other so-called “ethnic” jurisdictions. |

| ↵21 | Ibid, 81. This is not an explicitly prescribed policy in either the OCA parish bylaws (Article XII of The Statute of the Orthodox Church in America) or the ROCOR parish bylaws (Part IV). It is possible, however informally, to envision this type of bifurcation of authority taking place in parishes. |

| ↵22 | https://www.oca.org/statute/article-xii. (Accessed on 12/20/19). |

| ↵23 | Ibid. |

| ↵24 | Ibid. |

| ↵25 | https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ga-court-of-appeals/1060354.html (Accessed 12/20/2019). The court specifically noted that though the parish legally owned the property, the bylaws effectively nullified that reality in cases of “disobedience” to the hierarchy, diocese, or jurisdiction. |

| ↵26 | This was noted in the March 1, 1988 PA Supreme Court ruling to deny the OCA’s appeal of the previously unfavorable (to the OCA) court ruling in favor of the Mayfield parish. The documents containing the legal opinion/decision were acquired by this writer in October of 2019. |

| ↵27 | Quoted in Ferencz, American Orthodoxy and Parish Congregationalism, 103. The relevant section is GOASR II.1.XVII.1. |

| ↵28 | Ibid, 114. The Mayfield parish was certainly affected by the actions of St. Alexis Toth and his spearheading of a mass exodus from Greek-Catholicism to Russian Orthodoxy. The Mayfield parish officially began in 1891 as a Uniate parish and it was called the “St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Church.” In 1902, the parish placed itself under the omophor of the future St. Tikhon (Patriarch of Moscow), and in 1907 it was incorporated as “St. John the Baptist Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church.” The St. Alexis Toth story cannot be delved into here but he is an extraordinarily important figure in American Orthodoxy. Additionally, so-called “lay-societies” played an important role in the history of the Mayfield parish as well as other early American parishes. However, due to time and space constraints, their impact will have to be passed by in this paper. Both of these proximate causes noted by Ferencz are important to keep in mind when assessing the history and development of Orthodoxy in America generally, and the Mayfield parish specifically. |

| ↵29 | Ibid. |

| ↵30 | The Russian mission to Alaska would represent the “missionary” minded establishment of Orthodoxy. A well-trained clergy, with orders and procedures from its hierarchs, went to a foreign land and established parishes and literally trained the Alaskans to be Orthodox. St. Innocent and St. Herman come immediately to mind. This was not the case in the continental United States. |

| ↵31 | Ibid. |

| ↵32 | Ibid, 121. |

| ↵33 | Ibid, 164. |

| ↵34 | On 10/28/19 I received several hundred pages of Lackawanna County Court Documents (Various) in the case of Orthodox Church in America… Plaintiffs vs. Thomas Pavuk, Andrew Paserp, Rose Telep, John Doe, Jane Doe, Defendants… There were numerous appeals over a six-year period, and this produced a voluminous amount of documentation. This paper is essentially summarizing the existing documentation – no mean task. |

| ↵35 | This is a touchy subject and a legally significant one. One of the Mayfield arguments against the OCA was that they were initially under the ROCOR (they certainly were from 1935-1946 when the Metropolia returned to the ROCOR), and as such, they had a right to return. See the interview with Deacon Michael Pavuk, “We Should Respect one Another as Fellow Orthodox Even if We Have Differences of Opinion” (Accessed 8/19/2020). |

| ↵36 | From the “History of the Case” portion of the 1986 “Plaintiffs’ Brief in Support of Motion for Post-Trial Relief,” p. 33. The Plaintiffs filed their lawsuit with Lackawanna County on September 3, 1982 – just two weeks after the parish vote. |

| ↵37 | While this narrative is both tidy and legally valid, it is far from being accepted as the actual state of affairs by the other local Orthodox Churches. It was also not enough to convince the court that the Mayfield parish had no right to “secede” from it and join the ROCOR. |

| ↵38 | “History of the Case,” p. 38. |

| ↵39 | Later in the brief, the OCA noted the 1922 Ukase of Patriarch Tikhon which instructed the ROCOR’s supreme authority to disband. On the decree no 362 see Archpirest Nicholas Artemoff, “The Local Council of 1917-1918 as the Basis and Source for Decree No. 362 of November 7/20, 1920.” The text of Decree No. 362. |

| ↵40 | “History of the Case,” p. 5. |

| ↵41 | Ibid, 14. The conclusion of this line of argumentation is that the ROCOR should not have actually existed after 1922. |

| ↵42 | Ibid, 19. |

| ↵43 | “Defendants’ Brief in Support of Continued Control of Church Property by Local Parish,” p. 3. |

| ↵44 | Of particular note was the third term put forward by the Mayfield parish which stipulated that they did not have to repudiate or deny any “Unia” as they had always considered themselves Russian Orthodox. |

| ↵45 | “Defendants’ Brief…” p. 10. |

| ↵46 | Ibid, 11. |

| ↵47 | Ibid, 14. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 7. Quite ironic. |

| ↵48 | Ibid, 15. |

| ↵49 | Quoted in ibid, 18. |

| ↵50 | Ibid, 20-21. Meyendorff further admitted that Ukase 362 was the OCA’s canonical basis for legitimacy prior to 1970. This is an astounding admission, especially considering that Meyendorff claimed that the 1922 Ukase disbanded the ROCOR but evidently didn’t dissolve the Metropolia. |

| ↵51 | 1962 bylaws quoted in ibid, 22. |

| ↵52 | Ibid, 23. |

| ↵53 | Ibid, 24. |

| ↵54 | St. Michael’s Church located at 335 Fairmount Ave., Philadelphia, PA. |

| ↵55 | Ibid, 26. |

| ↵56 | Quoted in ibid, 27. |

| ↵57 | Lanier, Church Land Polity, 354. |

Picture Memories —

I used to look at this First Sobor Picture every day hanging on the green painted wall in the office of Archpriest George A. Gladky while the Christ the Savior Church was located at 1180 NW 99th Street Miami, Florida. Father George Gladky after leaving St. Tikhon Seminary where he had personally established the first bookstore and printing press there and with the blessing of now Saint Bishop Nikolai Velemirovich was sent to Miami, ROCOR church of St. Vladimir in Miami.

Father George specific to be the first English speaking priest in Florida ROCOR with that in print and designated mission for his ROCOR ordination, was upended by the local “very congregationalist” ROCOR parish council of the time rebelling against the hierarchical blessing and refusing to have English. On can see this documentation in the Orthodox Church in America, 1976 BiCentennial Red Book edition of history. There is Fr. George Gladky at St. Vladimir’s Miami, Florida with the yellow school bus, and painted name on it St Vladimir’s. This was early 1960’s. Does it sound familiar?

Let’s get real with today and see what history needs to do today prevent what happened in St. John the Baptist Cathedral, Mayfield, Pennsylvania 2020 recently witt the prison indictment of Romanchak the Youth director who had been at Jordanville Holy Trinity Seminary, St. Tikhin Seminary, and the St. John Youth Director solicitating sex over the internet with underage boys! https://www.thetimes-tribune.com/news/mayfield-man-caught-in-sex-sting-gets-up-to-35-years-in-prison/article_3412db34-52f2-525d-840d-32548468d68d.html

Let’s ask questions! What is wrong with this picture?

People would see this in the office of Fr George and question, ALL men, what is this?

Seeing all men made them the question.

I have been on the inside of Church Administration and know personally people in this picture of the Sober. I aided the monks of St. Tikhon’s and their book store effort at the first-ever OCA Sober to allow woman in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the early 1970’s.

What I can see from history is that the women and men retained by administrations that are engaged in wrongdoing are those who are willing enablers.

I am writing this because it was my prayer in the beginning of the year 2020 to not be an enabler. God’s first task for me, a land contract for our monastery in KORONA, (Mary’s Crown).

Why has ROCOR lost the St. Nicholas Monastery in Fort Myers?

Why has ROCOR lost the largest church in the Eastern Diocese in Dania (this is north of Miami)?

LIES, ENABLING, and its okay to sell women as Russian Soeaking Brides.

Does somebody out there maybe need to get the idea more real women to need to be involved in church administration?

That English speakers are being kept out of ROCOR missions in Flagler County that speak out there against closed doors, Russian only, which serves to enrich the pockets of local clergy selling the women. The sale of women is more open in the practices in Volusia County, Florida were professional “Prestige Dating Services” are allowed to take pictures inside the rented space where services are held and post them on Facebook and advertise for Russian Brides?

Where else is this happening now there is video streaming and limited attendance and restricted attendance in the parishes?

If Moscow is the preferred reference at this time, why does not Moscow send money for clergy salaries and stop HUMAN TRAFFICKING> Why is ROCOR not stopping HUMAN TRAFFICKING after losing parishes in Florida?

Where is repentance?

and

Priest Daniel Franzen

What was this priest doing when the Youth Director of St John the Baptist had access to vulnerable altar boys, and then convicted?

What are the implications of not discussing the how and why this happened and making change?

Parishes “pwning” their properties and not the diocese at one point in history kept them from bankruptcy when laws were broken and parish employees involved?

How many different ways will we pass the buck?

What does God see and know?

What will need to answer to each of us on the Day of Judgement if keep turning a BLIND EYE?

Look at history as my spiritual father Archmanindrite Roman Braga, who went through the fire of the Romanian Political Prison (Gulag) for being a teacher and teaching HIS STORY – God’s Story.

Shouldn’t our seminaries be teaching God’s story and we keep them accountable, to HIS WORD?

https://www.attorneygeneral.gov/taking-action/updates/case-update-lackawanna-county-church-youth-group-leader-arrested-for-child-sexual-abuse/

I don’t know who Mother Elizabeth is, but I find her comments inappropriate.

First of all, Fr Daniel Franzen’s article is specifically about the congregationalism of St John’s Parish and the effect of it on the parish history. Mother Elizabeth’s reply had little to do with the theme of the article.

Second, Mother Elizabeth apparently does not know about the events in the parish from experience. Newspaper accounts tend to sensationalise and distort.

I am the pastor of a neighbouring parish and am personally acquainted with Matthew Romanchak.

It saddens me that Mother Elizabeth drags into public view the sad story of one man’s sins and makes it food for gossip.

In reality, Matthew Romanchak has admitted to one single incident of a sin with a teenager. The sin, of course, is serious, and it is a crime because the other party was under age; however, this is not the molestation of young children. The victim was a teenager. A young person of that age knows the “facts of life.” In this case, the young person entered willingly into the sinful act.

For this one fall into grievous sin Matthew’s whole life has been ruined. The court gave him an unusually heavy sentence, probably because of his connexion with a church (where, by the way, he was not the “youth director,” but simply a reader.)

Sitting in prison, virtually in solitary confinement, Matthew is leading a life of repentance, like a real monk. He does not deserve to be made the fodder of angry invective, but rather compassion and prayer.

I don’t know why this case was brought up. But we all like gossip, don’t we?

Abbot German Ciuba you sinful sinful man. I hope that God has mercy on your soul. Although I do not believe in mercy for child abusers, or sympathizers of child abuse. I hope that he takes kindly to you and has mercy because that reply from you is straight evil, from the devil himself.