This article was written for the ‘Paisieva chteniya’ conference (Kyiv, November 2017), to mark the 295th year since the birth of St. Paisy Velichkovsky. The interview with the author: Three Dimensions in the Life of Dr Nicholas Fennell: England, Russia and Mount Athos.

A little over a quarter of a century has passed since the expulsion of the last Russian-speaking brotherhood from the Prophet Elijah Skete on Athos (PES). The skete is now run by a Greek brotherhood, who this year (2017) allowed S.V. Shumilo, director of the Athonite Legacy in Ukraine Institute, to see both the remains of the blessed Archimandrite Anikita (Shirinsky-Shikhmatov) and treasures connected with its founder, St. Paisy Velichkovsky. No Slav since the takeover of PES by the Greeks had been allowed such free access. After the expulsion, the library and other parts of the skete were placed under police guard, and heated battles were waged in the press and courts. Now that the dust seems to have settled, the events of 1992 can be more rationally reassessed.

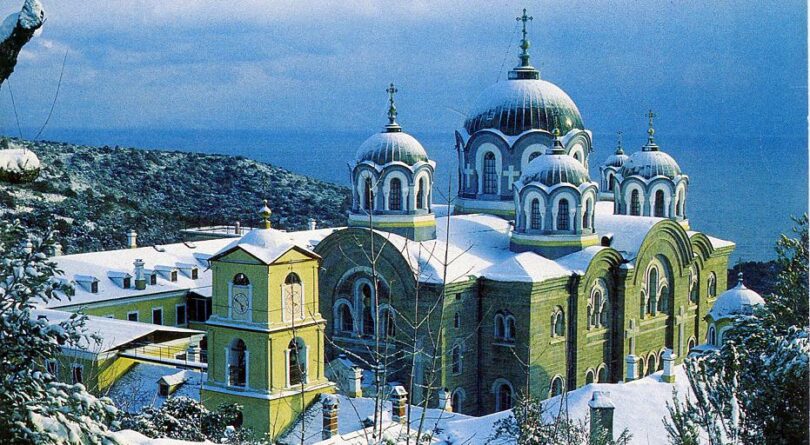

Since its founding in 1757, PES had continued to be in Russian hands. The eighty-odd Russian kellia, once substantial cenobitic monastic communities, had disappeared and were in ruins, and the mighty St. Andrew’s Skete had been taken over by its ruling monastery, Vatopedi, and adapted to house the Athoniada School. Until the 1960s there were fears that even St. Panteleimon’s would cease to be a Russian monastery and might be taken over by the Greeks, as it had been in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

In 1992, the St. Panteleimon antiprosopos (Karyes representative) at the time, Priest-Monk Nikolay (Generalov), wrote a detailed report for the Patriarch of Moscow and the Holy Russian Synod about the expulsion. [1]‘O sobytiyakh na Afone’, published in Pravoslavnaya Rus´, 1993, No 12 and 13. All subsequent quotations in this article are from his report, other than those mentioned in the footnotes below. … Continue reading He summarises what happens thus:

“… on 7 May (O.S.) 1992, an exarchate of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, comprising Metropolitans Athanasios of Ilioupolis and Meliton of Chalkidon, who were assisted by a commission of the Athonite Holy Koinotis represented by the antiprosopoi of Iviron, Pantokratoros, Agiou Pavlou, Stavoronikita and Xenophontos, and backed up by the assistant governor, Mr Nikolaos Papadimitriou [2]The governor himself, Konstantinos Papoulidis, a friend of the Slavs, had gone home to celebrate his name day (according to the New Style). In the autumn of 1992, he resigned in protest against the … Continue reading and the police, but unbeknownst to the other members of the Holy Koinotis — i.e. acting extrajudicially — expelled from both the skete and Mount Athos the four inhabitants of the Russian Prophet Elijah Skete. Two of the inhabitants were enrolled in the [Ruling] Monastery monachologion and were Greek citizens. The [expelled fathers] were given one hour to gather their belongings”.

According to Fr. Nikolay, the principal reason for the expulsion was clear enough: “Fr. Seraphim [Bobich, the prior] and his brotherhood did not recognize the New Calendarist Ecumenical Church. For this reason, they did not commemorate His Holiness the Ecumenical Patriarch, and this was a clear breach of the Athonite typikon”.

The expulsion itself, however, was carried out not merely ‘extradujicially’ but also hastily and secretively. There was no official warning of the exarchal visit. Rumors had been circulating in the Athonite community a month before that the patriarchate would send an exarchate to convert Pantokratoros into a cenobium and sort out PES, its dependent house, which was to be handed over to a Greek brotherhood. Furthermore, the skete must have been aware of the danger they were facing. As Fr. Nikolay puts it, ‘Fr. Seraphim and the brotherhood had been warned that they would be expelled from Athos if they persisted in not commemorating the Ecumenical Patriarch.’ But that was all unofficial.

Eventually, the Koinotis received a telegram from the Patriarchate that the exarchate would arrive on 12 May, but at 9.45 p.m. on 4 May the Protos, Priest-Monk Athanasios of Vatopedi, received a telephone call from the Phanar informing him that the exarchate would arrive in Karyes the very next day. By 4 p.m. on 5 May the metropolitans had arrived at Ouranoupolis. This was a breach of protocol: no official visits to the Koinotis were usually received without written notification. Three hours later, the exarchate was in Karyes.

Before their meeting with all the twenty representatives that make up the Koinotis, the metropolitans had individual, private conversations with a select few antiprosopoi. They then read the telegram to the general assembly and explained that their hasty and unexpected arrival was due to ‘a lack of time and much to accomplish, and to their having to come a week earlier than planned’. Their mission was to install a new cenobitic brotherhood in Pantokratoros and get rid of the old idiorrhythmic community, which was ‘undesirable to both the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Koinotis’. Not a word was said about PES.

The whole of the next day, Tuesday 6 May, the exarchate carried out its mission at Pantokratoros. It returned there on Wednesday morning, on the Feast of Mid-Pentecost, to finalise the previous day’s arrangements and formally to install the new abbot. Meanwhile, the governor’s secretary, Mr Omiros, came to PES to say that the exarchate was at the governing monastery and was likely to pay the skete a visit, but that there was nothing to be concerned about. Nobody in Karyes knew exactly what was going on.

At 4 o’clock that Wednesday afternoon Fr. Nikolay was told over the telephone that the exarchate and those accompanying it were at PES. He also learned that Metropolitan Meliton, having hastily returned to Karyes, was trying to persuade the Kelliot, Priest-Monk Paisios, to become the skete’s new prior immediately. The latter asked to have time to think over the proposition: he later refused. That evening a Greek Athonite acquaintance of Fr. Nikolays’ urgently knocked at his door and informed him that the four inhabitants of PES were being taken to Dafne on their way out of the Holy Mountain.

On the morning of the next day, Thursday 8 May, a meeting of all twenty Koinotis representatives was at last held in Karyes. Metropolitan Meliton began by ‘courteously asking for forgiveness for their omitting in their haste to read the Ecumenical Patriarch’s letter’, which he invited the Koinotis secretary to read. In the minutes of the meeting, it was, however, recorded that the letter had been read at the first meeting, on Monday, and that the exarchate’s actions were unanimously approved of by the Koinotis. Again, the PES expulsion was not mentioned. Fr. Nikolay strongly protested about the treatment of the skete fathers and asked that the minutes record the reservations of St. Panteleimon Monastery. The Pantokratoros Antiprosopos told Fr. Nikolay that:

“PES stands on monastery land and thus belongs to the monastery. He, therefore, asked [Fr. Nikolay] not to interfere in the monastery’s internal affairs. Those expelled were not the skete’s Russian inhabitants, but Americans, and the prior of the skete, Archimandrite Seraphim, was, as far as the monastery was concerned, not a monk but an American gangster”.

The Pantokratoros representative’s seemingly absurd slander against Fr. Seraphim is extraordinary for its evidently heartfelt venom. The antiprosopos was not merely expressing the antipathy which the monastery had harbored against its dependent skete for over a century [3] For detailed analyses of the quarrel between the two houses, see Gerd, L.A., Russky Afon 1878–1914 gg. (Moscow: Indrik, 2010), pp. 60–73, and Fennell, op. cit., pp. 25–69. ; a more general anti-Russian phyletism was voiced at the meeting by the metropolitans, who claimed that “the skete is situated not on Russian, but Greek land, and belongs to Pantokratoros; there neither is nor ever has been any such thing as a Russian PES”.

This view is a little different from that of certain Greeks since the 1870s who believe that St. Panteleimon Monastery has always been Greek and was usurped by the Russians.

Why then the animosity against Prior Seraphim? In 1970 Fr. Seraphim (Bobich) came from the United States to the skete where he found a handful of old and infirm fathers. The then Prior, ninety-year-old Archimandrite Nikolay, was suffering from progressive general sclerosis. He handed over responsibility for the house to Fr. Seraphim in 1973, the year of his death, instructing him strictly to uphold certain principles: since 1924 the skete objected to and had nothing to do with the New Style Calendar [4] Fennell, op. cit., p. 281, Minute 28. ; the skete strongly protested against any form of ecumenism, and no ecumenical patriarch was commemorated in the skete services. The newcomer was zealously determined to stick to these principles.

Archimandrite Seraphim had tireless energy. Within a year of his arrival, he “set about completely refurbishing the central church and the other [skete] buildings. Over the recent years, owing to a lack of manpower, many of the skete’s buildings were in poor shape through lack of maintenance. Now, thanks to Fr. Seraphim’s efforts, the broken windows are being replaced, old paintwork is being renewed, holes in the rooves are being stopped, and the living quarters are being cleaned and thoroughly refurbished. At the same time, all church services according to the typikon are [again] being served”. [5] Pravoslavnaya Rus´, 1971, No 13.

Fr. Seraphim must, of course, been helped by volunteers and perhaps even hired workers. When I used to visit the skete, over the decade before the expulsion, the vast central church, the second largest on the Holy Mountain, and the external fabric of the other buildings, seemed immaculate: a single man could not have restored them on his own; but I saw for myself how indefatigable and hard-working he was.

His tireless energy was coupled with almost messianic zeal and unpredictable moods: “According to several monks, Fr. Seraphim easily lost his temper and at the slightest provocation would publicly rant about ecumenists and masons. The priest Valery Luk´yanov, however, saw him in a different light: ‘We were met by Fr. Seraphim (Bobich)… What a kind monk, and an impressive sight, with his penetrating blue eyes! When he heard that we belonged to ROCOR he greeted us with great warmth.’” [6] Troitsky, P. Writing in Fennell et al., op. cit., pp. 151–2.

When the skete fathers were surrounded by armed police and arrested on 7 May, Fr. Seraphim shouted at them, calling the exarchate commission Judases, antichrists, and communists. Justifying these insults, he explained to Fr. Nikolay (Generalov) on the telephone a few days later that their actions were nothing short of criminal because they invaded the skete ‘like uniates’.

Since his arrival at the skete Fr. Seraphim had written regularly to the organ of the Russian Orthodox Outside Russia (ROCOR), Pravoslavnaya Rus´. At Christmas and Easter almost every year Fr. Seraphim would lodge impassioned appeals in the journal, such as the following:

“Christ is risen! … Dear children of the Holy Russian Orthodox Church! You well know what an unrelenting and difficult path of martyrdom our people in the Motherland and scattered abroad are treading while preserving Holy Orthodoxy in its purity. We Russian Athonites desire with all our hearts that our Orthodox brothers preserve the essential steadfastness and necessary respect for the ancient ecclesiastical traditions in order that we may safeguard our sacred treasure, the Orthodox Church, in these exceedingly unfavorable historic conditions of apostasy… With great joy, we inform all [our] benefactors that, thanks to the spiritual and material aid of the Russian diaspora, our [central] church, belfry, and library are being refurbished… As the years go by our small brotherhood experiences evermore the love of the Russians abroad for our holy house”. [7] Ibid., 1977 No 2.

Fr. Seraphim’s appeals emphasized the suffering involved in following the straight and narrow path. A favorite quotation of his was Matthew VII 14: ‘strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.’ The Mother of God, he claimed, gave strength to the few, who ‘have true faith alien to all the heresy and compromise of our apostatical twentieth century.’ [8] Ibid., 1978 No 8. The most extreme expression of his zealotry was expressed in an open letter on behalf of the expelled PES brethren in the summer of 1992:

“From the 1920s, the ecumenist and modernist policies of the Constantinople Patriarch has led to schisms in the Orthodox Church and in the flock of the patriarch himself — including the Holy Mountain… In these complex and difficult circumstances, we pledged our obedience to the dying wishes of skete’s prior, Archimandrite Nikolay of blessed memory. We consider his position to be entirely in accordance with the holy canons and the works of the holy fathers. Under Fr. Nikolay’s guidance, the skete ceased to be in communion with Patriarch Athenagoras in 1957 when he openly espoused an ecumenist, uniate policy, thus dividing the Orthodox Church… [which] has been adorned with many holy martyrs. Is this not the case today, when Hindus, Buddhists, Moslems, Jews, and Uniates cruelly persecute the Orthodox?” [9] Ibid., 1992 No 16.

I often met Fr. Seraphim at the skete and saw for myself the contradictory character of this extraordinary man. He was charming and welcoming, and had a certain presence. One night I took the liberty of singing with Fr. Ioanniky at the right-hand kliros without the prior’s blessing. Fr. Seraphim came out of the sanctuary in his vestments during the canon and asked me which church I went to. When he found out that I attended the services at 1 Canterbury Rd Oxford, and that I went to confession with Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia (Constantinople Patriarchate), he told me to stand outside in the narthex. The next day he graciously apologized to me but explained that the true Orthodox Church had no truck with the new calendarists, ecumenists, uniates and friends of Buddhists; and he quoted to me Matthew VII 14.

It seems, then, that the expulsion of the skete fathers was due largely to animosity against the prior, who was never afraid of speaking his mind and felt duty-bound to oppose the patriarch. If, however, the expulsion was due merely to a personal vendetta, its brutality is hard to justify. Fr. Nikolay (Generalov) was told that precious vestments were taken from the skete: Metropolitan Meliton is said to have taken some for himself; a metal safe containing mitres and gold brocade was broken into and plundered. As Bishop Kallistos put it:

“Of course, from the patriarchate’s viewpoint, [the skete fathers] were in an irregular canonical position. But at the same time, they were sincere and devout men, peacefully following a strict life of prayer, who had kept the monastic property in good repair, and their refusal to commemorate the Patriarch was based on deeply held grounds of conscience. The way in which the patriarchal delegation sought to settle this question of conscience through the use of force and violence can only be deplored. The monks were treated in an altogether barbaric fashion. <…> The skete, hitherto always Russian, has now been taken over by Greek monks. The ecumenical patriarchate says the expulsion is not to be seen as an anti-Russian measure, but the facts speak for themselves”. [10] Kallistos, Bishop of Diokleia, ‘Athos after ten years: the good news and the bad’, Sobornost, 15:1, 1993, p. 34.

In his report to the Patriarch and Holy Synod of Moscow, Fr. Nikolay (Generalov) points out that there were serious inconsistencies and illogicalities in the expulsion: “I also pointed out [to the metropolitans] that almost half the Athonite population do not commemorate the patriarch because they are zealots. There are also on the Holy Mountain so-called Hexagonists, who do not even recognize the Resurrection. Why then have they not been expelled from Athos?”

Attempting to answer this question, Fr. Nikolay points out that the former abbot of Philotheou, Archimandrite Ephraim, left for America and joined ROCOR. The Ecumenical Patriarchate, therefore, acted in a fit of pique at this defection. This seems a far-fetched explanation. It is more probable that the expulsion was simply a reaction to the prolonged and strident defiance of an individual, who was openly flouting the rules and challenging the hierarchical authority of the church. There were and are numerous zealots on Athos; Esphigmenou continues to be in defiance: punishing just four rebels, on the other hand, is easier than dealing with many.

Although the manner of the expulsion is unjustifiable, challenging authority goes against the core monastic principle of obedience. I thus had no right to sing without asking for the prior’s blessing. Fr. Nikolay (Generalov) himself acted out of line. He made public not only his letter to the Moscow Patriarchate but also his conflict with the abbot and authorities of his own monastery. In an interview he gave in 2008 to a Russian journalist, he said:

“When the Greeks seized PES, my opinion on the matter differed from that of the abbot and the pneumatikos [Father-Confessor Makary], who demanded that I sign the minutes [of the Koinotis meeting with the exarchate on 8 May] [while giving a note of the monastery’s] abstention. It occurred to me that I ought to respond differently to all this, but I was ordered to abstain… I wanted at the time to record the monastery’s differing view, but I was forced to put my signature [to the abstention]”. [11] Kholodyuk, Anatoly. Eto bozhie blagoslovenie — byt´ nasel´nikom na Afone, http://pravoslavie.ru/28260.html, 2008.

As a result of his disagreement with his senior colleagues at the monastery, Fr. Nikolay resigned as antiprosopos. In 2004, he was moved out to Xylourgou Skete, and several years later to Kroumitsa. [12]Perhaps Fr. Nikolay has been pardoned or at least is less in disgrace. In June 2017, he accompanied the new Abbot Evlogy (elected the previous year, upon the death of Abbot Ieremiya) on an official … Continue reading

Will the Russians ever return to PES? In 1821, most of the Athonite community fled the Holy Mountain for fear of Turkish persecution. Prior Parfeny and his brotherhood presented to Alexander I a piece of the True Cross and other relics they had brought with them from the skete. The emperor told them to keep the relics safe and be patient: eventually, they would return to Athos. [13] Fennell, op. cit., p. 80. With patience and in time, perhaps the lamp of Russian monasticism will burn brightly once more in the house founded by St. Paisy Velichkovsky, whose birth 295 years ago is being celebrated this month.

References

| ↵1 | ‘O sobytiyakh na Afone’, published in Pravoslavnaya Rus´, 1993, No 12 and 13. All subsequent quotations in this article are from his report, other than those mentioned in the footnotes below. Fr. Nikolay (Generalov’s) report was published later in afonit.info, the online Athonite journal: http://afonit.info/biblioteka/afon-i-slavyanskij-mir/ilinski-skit-na-afone; and in a number of other Russian sites, such as http://cliuchinskaya.blogspot.co.uk/2015/10/blog-post_30.html. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | The governor himself, Konstantinos Papoulidis, a friend of the Slavs, had gone home to celebrate his name day (according to the New Style). In the autumn of 1992, he resigned in protest against the ill treatment of the Athonite Slavs by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. See Fennell, N., et al., Il´insky skit na Afone, (Moscow: Indrik, 2011), p. 74, fn. 94. |

| ↵3 | For detailed analyses of the quarrel between the two houses, see Gerd, L.A., Russky Afon 1878–1914 gg. (Moscow: Indrik, 2010), pp. 60–73, and Fennell, op. cit., pp. 25–69. |

| ↵4 | Fennell, op. cit., p. 281, Minute 28. |

| ↵5 | Pravoslavnaya Rus´, 1971, No 13. |

| ↵6 | Troitsky, P. Writing in Fennell et al., op. cit., pp. 151–2. |

| ↵7 | Ibid., 1977 No 2. |

| ↵8 | Ibid., 1978 No 8. |

| ↵9 | Ibid., 1992 No 16. |

| ↵10 | Kallistos, Bishop of Diokleia, ‘Athos after ten years: the good news and the bad’, Sobornost, 15:1, 1993, p. 34. |

| ↵11 | Kholodyuk, Anatoly. Eto bozhie blagoslovenie — byt´ nasel´nikom na Afone, http://pravoslavie.ru/28260.html, 2008. |

| ↵12 | Perhaps Fr. Nikolay has been pardoned or at least is less in disgrace. In June 2017, he accompanied the new Abbot Evlogy (elected the previous year, upon the death of Abbot Ieremiya) on an official visit to the Patriarch of Bulgaria. |

| ↵13 | Fennell, op. cit., p. 80. |