From the Editor

Metropolitan Sergii (Stragorodskii), later Patriarch, is one of these church figures who deserves very careful treatment due to the impossible choices they faced. [1]One can get an impression of the subject matter from my article “Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhny Novgorod as Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens to Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy” … Continue reading

The Act of Canonical Communion signed by Patriarch Alexis and Metropolitan Laurus on May 17, 2007, contains the following provision: “Acts issued previously which preclude the fullness of canonical communion are hereby deemed invalid or obsolete.” Therefore, the ROCOR’s 1943 decision not to recognize Patriarch Sergei’s election as canonically valid is now redundant. I understand that in the process of negotiations leading to full communion, both parties agreed to respect the fathers of both the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Church Abroad.

The possible canonization of Metropolitan Sergii goes beyond this. The publication of this research strives to contribute toward a thoughtful conversation within the united Russian Church along the lines of this website’s mandate: “conversations about the past are based upon historical methodology with a healthy respect for each subject researched, and an indiscriminate approach to the facts studied. Dialogue about the present stipulates the same methodology for those who recognize the value of candid conversation.”

The article offered to readers’ attention below was published in Der Bote/Вестник (the official press organ of the ROCOR Diocese of Germany), No. 3, 2024. It is being published on our site in an abbreviated and revised form. The translation of this text has been sponsored by Australian and New Zealand Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev

March 5, 2025, Jordanville, New York

As advertised on the site of the Moscow Patriarchate, [2]“V Moskve sostoialasʹ nauchnaia konferentsiia «Patriarkh Sergii i ego dukhovnoe nasledstvo»” [A Conference in Moscow on ‘Patriarch Sergii and His Spiritual Legacy’”. Moscow Patriarchate … Continue reading on May 15, 2024, in the parish house of Holy Epiphany Cathedral in Elokhovo, Moscow, a conference was held on “Patriarch Sergii and His Spiritual Legacy” (a title shared by a book [3] Patriarh Sergij i ego duhovnoe nasledstvo. Moscow: Moscow Patriarchate Press, 1947. about Patriarch Sergii published in Moscow in 1947). One of the conference organizers was Prof. Aleksandr V. Shipkov, a professor of the Russian Orthodox University of St. John the Divine, a long-time apologist for the canonization of Patriarch Sergii (Stargorodskii). [4]“V RPTs ne iskliuchaiut, chto Patriarkh Sergii budet kanonizirovan” [ROC Does Not Preclude Possibility of Canonizing Patriarch Sergii] RIA Novosti. April 5, 2016. URL: … Continue reading

Apart from this, the conference saw the participation of Olga Vasilʹeva, President of the Russian Academy of Education, who previously held the post of Minister of Education of the Russian Federation (2018–2020). Ex-minister Vasilʹeva’s talk likened Patriarch Sergii’s ministry to martyrdom. Previously, as a member of the Russian government, she had spoken out in favor of Patr. Sergii’s canonization. [5]A statement to this effect was made during the Parsuna program moderated by Vladimir R. Legoida on the SPAS TV channel on July 1, 2018. Arkhangelsk Diocese official Web site. URL: … Continue reading

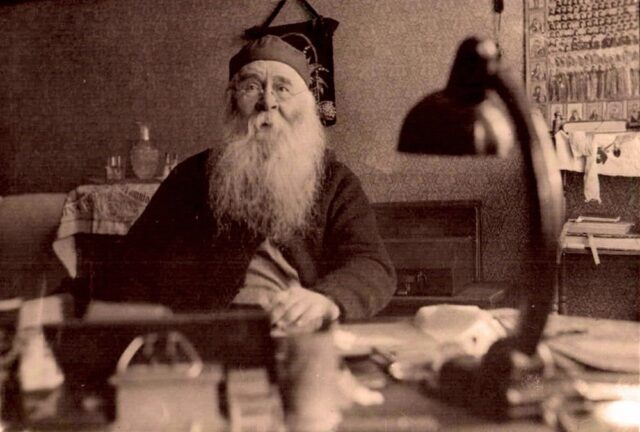

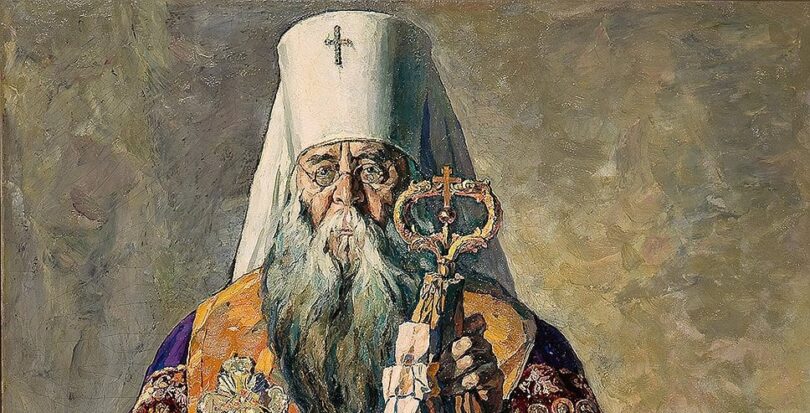

Metropolitan Sergii (Stargorodskii) (1867–1944). 1943

In the talk [6] Official site of the Moscow Patriarchate. URL: http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/422558.html?ysclid=lwsvpe5x35554537867 (accessed January 15, 2025). delivered by Metropolitan Iuvenalii (Poiarkov) of Kolomensk, President of the Synodal Commission for the Canonization of Saints, at the Millennial Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church (August 13–16, 2000) at the Church of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, it was said The Committee members did not find any grounds for the canonization of persons who compromised themselves or others under questioning, thereby making themselves the cause of the arrest, torment, or death of totally innocent people, regardless of the reason for their suffering. Lack of faith demonstrated by them under such circumstances cannot be deemed exemplary, for canonization is a witness to the sanctity and courage of a saint, whom the Church of Christ calls upon Her children to emulate.

These are the criteria for sainthood. And yet, during the years of the Stalinist purges in the USSR, the opposite phenomenon came to be widespread: public denunciation as a genre of political publicity. Oppressive measures against broadly familiar public, academic, cultural, and religious figures who were respected by their fellow citizens, were always preceded by public slander (denunciation) leveled against them in the Soviet press by colleagues “from the factory floor”. To take two representative examples, the talented young poet Pavel N. Vasilʹev (1910–1937), was hounded in the newspapers by the “court” author Maxim Gorky; [7]“O literaturnykh zabavakh” [On Literary Pastimes]. Pravda, No. 162, June 14, 1934; “O literaturnykh zabavakh”. Izvestiia TsIK SSSR i VTsIK [Bulletin of the Central Executive Committee of the … Continue reading the outstanding biologist Nikolai I. Vavilov (1887–1943) was tarred in the papers and in journals by the middling biologists Aleksandr K. Kolʹ and Isaak I. Prezent. [8]V. D. Esakov. Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov. Stranitsy biografii [Pages from the Biography of Nikolai I. Vavilov]. RAS Institute of Russian History, Nikolai Vavilov Academic Legacy Commission. Moscow: … Continue reading Before arresting them, the Soviet authorities sought to tarnish the reputation in the media of such popular figures who had become “inconvenient” to them, subject them to public censure, delegitimize them, and place them outside the bounds of the law in the eyes of their fellow citizens, as became inevitable subsequent to their arrest.

It was not even a requirement for those who slandered and publicly denounced their colleagues in the press to be included in the case files fabricated by the Soviet security services (OGPU, NKVD, NKGB); their documented “statements of evidence” might not even be among the “evidence” collected by prosecutors. They might not even be mentioned in the case files of their victims.

However, one result of such publications in the period of mass political repressions in the 1920s–early 1950s was often the arrest and illegitimate condemnation of those targeted by these publications (the poet Pavel Vasilʹev [9] Kunaev, op. cit.; Petrov, op. cit.; Kashina, op. cit. was executed by firing squad at Lubianka in 1937; Academician Vavilov [10]M. A. Popovskii. Delo akademika Vavilova [The Case of Academician Vavilov]. Moscow: Kniga. 1990 (1991). 304 pp.; Peter Pringle. The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin’s Persecution of … Continue reading was starved to death in a Saratov prison in 1943; etc.). Public denunciations turned the wheels of political terror in the USSR and were a driving belt for mass repressions.

In this way, the denouncers might not have a formal relation – one expressed in case files, minutes of questioning, or internal memoranda – to the illegal condemnation of those whom they were denouncing, publicly accusing, or slandering in the press, which does not do away with their moral or legal responsibility for the public repressions against their fellow citizens whom they had subjected to public libel and for the subsequent fate of the same, be it torture, execution, concentration camps, prisons, exile, illness, maiming, etc. In the Stalinist USSR of the 1930s, public denunciation became inextricably intertwined with the system of mass political terror and an instrument of inciting extrajudicial [11]In the Stalinist USSR, the practice of convictions and reprisals against citizens without public trial was widespread; sentences were handed down by several officers of the state security bodies … Continue reading reprisals against “inconvenient” fellow citizens.

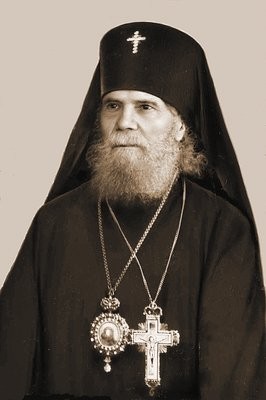

Archbishop Daniil (Iuzvʹiuk) of Pinsk and Polesia (1880–1965), 1948

After the start of World War II, not only did the genre of public denunciation not lose relevance in the USSR, but indeed began to be wielded actively within Church walls, crazy though that may sound. This time around, it was Metropolitan Sergii Stargorodskii, the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne, who diligently performed the role of the public denouncer of his “fellow workers from the factory floor”. In his “Encyclical to the Children of Our Orthodox Russian Church in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, of September 22, 1942,” [12] Pravoslavnaia Entsiklopediia. URL: https://www.sedmitza.ru/lib/text/439922/ (accessed January 15, 2025). Metropolitan Sergii cames down with accusations of “a fascist turn” on his fellow bishops in the Baltic, which was occupied by German forces (Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii, [13]M. V. Shkarovskii. “Mitropolit Sergii (Voskresenskii) i ego sluzhenie v Pribaltike i na Severo-Zapade v 1941–1944 gg.” [Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii and His Ministry in the Baltics and … Continue reading Archbishop Iakob Karps, [14] “Sinodik Pskovskoi missii” [The Pskov Mission Synodicon]. Sankt-Peterburgskie eparkhialʹnye vedomosti, 26–27 (2002), p. 9. Bishop Pavel Dmitrovskii, [15] Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate 9/1945, pp. 45-46; 7/1946, p. 4. Bishop Daniel Iuzvʹiuk [16]Hieromonk German Rosnianskii. “Arkhiepiskop Daniil (Nekrolog)” [Obituary: Archbishop Daniil]. Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate 11/1965, pp. 22–24; Archbishop Manuil Lemeshevskii. Russkie … Continue reading).

In his “Encyclical to the Orthodox Flock in Rostov-on-Don and Rostov Diocese, March 20, 1945,” [17] Pravoslavnaia Entsiklopediia. URL: https://www.sedmitza.ru/lib/text/439937/ (accessed January 15, 2025). the future Patriarch Sergii publicly slandered the ruling bishop and honored archpriests of this South Russian diocese (Archbishop Nikolai of Amassia, [18]Metr. Manuil (V. V.) Lemeshevskii. Russkie pravoslavnye ierarkhi perioda s 1893 po 1965 gg. (vkliuchitelʹno) [Russian Orthodox Hierarchs from 1893–1965]. Erlangen, 1979–1989. Vol. 5, … Continue reading Achpriest Ioann Nagovskii [19] G. I. Trofimov. “Polkovoi batiushka” [A Priest for the Troops]. Posev 5/2022, pp. 28–35; 6/2022. pp. 34–42. and Fr. Viacheslav Serikov [20] G. I. Trofimov G.I. “Protoierei Viacheslav Serikov”. Chetyrnadtsatye Konstantinovskie kraevedcheskie chteniia im. A.Koshmanova. Rostov-na-Donu: Alʹtair, 2022, pp. 422–439. ) on working “at the Germans’ behest”. Apart from this, Metropolitan Sergii Stargorodskii claimed that all of the Don clergymen listed above had committed a canonical infraction: “at the same Germans’ behest, they approached the Romanian Patriarch with a request to receive the Diocese of Rostov into his authority”, which was a lie and was definitively rebutted [21] FSB Directorate Archive for Rostov Region. П-49273. Vol. 1. ff. 53, 53v, 58. by Bishop Iosif Chernov of Taganrog, Vicar of the Diocese of Rostov, [22]V. Koroleva. Svet radosti v mire pechali: Mitropolit Alma-Atinskii i Kazakhstanskii Iosif [The Light of Joy in a World of Grief. Metropolitan Joseph of Almata and Kazakhstan]. Moscow: Palomnik. 2004. … Continue reading who was serving at the time.

Some time later, those of the Russian bishops and clergymen mentioned in the public denunciations listed here who made it until the Red Army came were subjected to political repression from the part of the Soviet security services (NKGB/MGB) – for instance, Archbishop Daniil (Iuzvʹiuk) of Pinsk and Polessia, and Archpriest Viacheslav A. Serikov, Dean of the city churches of Rostov-on-Don. To what extent did Metr. Sergii’s slander have an influence on their arrest and on the fabrication of criminal cases against them, and on their subsequent sentencing to captivity in Soviet camps? The former spent 5 years in captivity and lost his sight, and the other 8 years, losing his life in the process. What is the share of responsibility and involvement of Metr. Sergii in these iniquities which came to pass?

Can we not apply to this situation the words of Metropolitan Iuvenalii Poiarkov’s talk to the Jubilee Council (2000): “The Committee members did not find any grounds for the canonization of persons who compromised themselves or others under questioning, thereby making themselves the cause of the arrest, torment, or death of totally innocent people”? In what way is compromising someone in public “better” than doing so under torture? Why should the conclusion to the Synodal Comission cited above not be relevant to the figure of Patriarch Sergii?

The fact that Archbishop Daniil was compromised by Metr. Sergii is confirmed by the fact that he was amnestied immediately after Stalin’s death in 1955, having spent 5 years, or ⅕ of his 25-year sentence, in captivity. If indeed Archbishop Daniil’s case had included proven facts concerning his “fascist turn”, of which he had been accused by Metr. Sergii, then he would not have been amnestied in 1955 and would not have been given the right to settle in the town of Izmail (Odessa Region, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic) on the southern Danube and serve in the cathedral there. [23]Priest F. Golikov and S. V. Fomin. Krovʹiu ubelennye: Mucheniki i ispovedniki Severo-Zapada Rossii i Pribalktiki (1940–1955) [Whitened by Blood: Martyrs and Confessors of North-western Russia … Continue reading

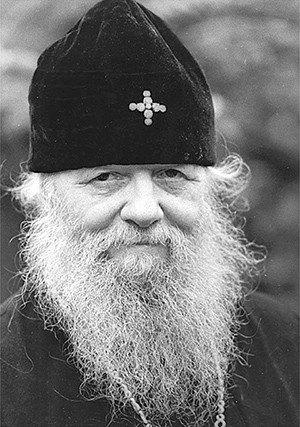

Metropolitan Iosif of Almata and Kazakhstan, ca. 1970

By contrast, Bishop Iosif Chernov of Taganrov, arrested by the NKGB in the summer of 1944 on similar charges, served his full 10-year sentence in a Soviet concentration camp, and after being released in 1954, he spent two more years, until 1956, in exile in the remote steppes of Kazakhstan with a strict ban on ministry. [24]Archive of the Department of the Committee of National Security of the Republic of Kazakhstan for Akmola Region, Item 3378; Central Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Fonds 1709, Series 1, … Continue reading

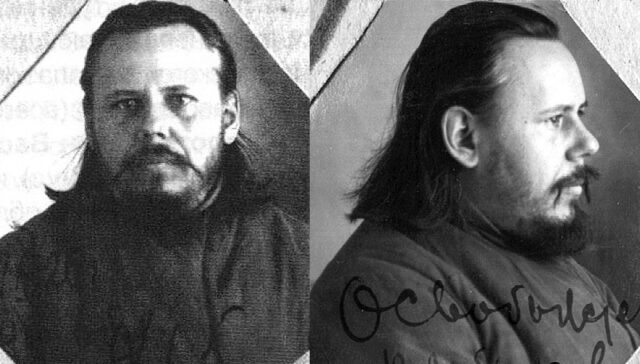

Archpriest Viacheslav Serikov, who did not survive the harsh conditions of his imprisonment, departed to the Lord in the place of his imprisonment in the Northern Urals on May 20, 1953. After examining case file П-54273 with charges of “high treason”, on June 18, 1993, the Rostov Region procurator resolved to rehabilitate Fr. Viacheslav A. Serikov. In this way, Metr. Sergii’s public slander against Fr. Viacheslav was rebutted.

Apart from this, one of the Russian bishops publicly denounced by the future Patriarch Sergii, Metr. Sergii Voskresenskii of Vilnius and Lithuania, [25] Shkarovskii, “Mitropolit Sergii…”; Idem, “O. Ilia…”; Gerich, op. cit.; Alexeev, op. cit. was fatally shot by unknown persons on the desolate road from Vilnius to Kaunas.

Testimony has survived from the Riga priest Fr. Nikolai N. Trubetskoy (1907–1978), an active participant in the Pskov Mission (1941–1944), concerning the murder of Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii by Soviet partisans on the orders of the NKGB, referring to the admission of a former partisan whom he had met in prison. [26]N. Shemetov. “Edinstvennaia vstrecha pamiati o. Nikolaia Trubetskogo” [The Sole Memorial Event for Fr. Nikolai Trubetskoi]. Vestnik russkogo khristianskogo dvizheniia [Bulletin of the Russian … Continue reading There is no documentary confirmation of these words as of yet, but not all of the NKGB archives have been declassified at the present tiome. If we assume that the former partisan did not lie to Fr. Nikolai, then what happened does not cast a favourable light on Metropolitan Sergii Stargorodskii, who had blamed his fellow Metropolitan of a “fascist turn” in an Encyclical dated September 22, 1942. We thus come to a fundamental issue: did the public words of the future Patriarch Sergii serve as a weighty argument in favor of the decision to kill the Exarch of the Baltic States, or did it not? After all, during the war, any citizen of the USSR whom the Soviet state viewed as having “turned to fascism” was a legitimate target and could be “liquidated” without trial “according to wartime laws.” This is all the more so since we are talking about a major religious leader whom officials of the Council for the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church under the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR had already termed “excommunicated from the Church a traitor to the Motherland” in secret correspondence dating to 1943. [27] Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 137–138; Russian State Archive. Fonds 6991, Series 2, Item 2, f. 149.

Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii (1897–1944), Exarch of the Baltic, 1941

Andrei V. Gerich (1919–2014), a parishioner of the Exarchate of the Baltic, who lived in Latvia until 1944, is likewise sure [28] Gerich, op. cit.; Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 138–139. of the Soviet trail in the case of the murder of Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii. The decision to liquidate Metr. Sergii may have been taken at a low level, for example, by local Soviet partisans and members of the underground movement who were operating in the Baltics during the occupation, among whom Metr. Sergii’s September 22, 1942, encyclical had been circulating.

Therefore, as long as the murder of Metr. Sergii Voskresenskii of Vilnius and Lithuania fails to be cleared up or investigated, we cannot ascertain how serious the consequences of Metr. Sergii Stargorodskii’s public accusations of the former’s “fascist turn” were. The conclusion of the Second Directorate of the NKGB of the USSR that the German occupying authorities were culpable for Metr. Sergii’s murder, founded on the statements of the renegade Archimandrite Filipp Morozov, cannot fail to raise doubts, [29] Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 128–137. much less can it stake a claim to “impartiality”. Thus the probability remains that these very words turned out to be fatal and predetermined the fate of the Baltic Exarch. A little over two weeks after Metr. Sergii Voskresenskii was executed, Patriarch Sergii died in Moscow on May 15, 1944, officially from an brain hemorrhage. The ecclesiastical historian and professor Wassilij I. Alexeev [30]V. V. Agenosov. Vosstavshie iz Nebytiia. Antologiia pisatelei Di-Pi i vtoroi emigratsii [Those Who Reemerged from Non-Being: An Anthology of DP and Second-emigration Russian Writers]. IRO 22. Saint … Continue reading (1906–2002) thought that this was how Patriarch Sergii was affected by Metr. Sergii Voskresenskii’s death… [31]Alexeev, op. cit.; Idem. “Le drame de l’exarque Serge Voskresenskij et l’élection du patriarche de Moscou à la lumière des documents confidentiels allemands”. Irenikon 2/1957, … Continue reading

The grave public accusations leveled by the Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metr. Sergii against the innocently killed Metr. Sergii Voskresenskii were not confirmed by a single court in the world.

As late of May 1935, the Temporary Patriarchal Holy Synod under the aegis of Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metr. Sergii Stargorodskii, under pressure from the Soviet regime, “dissolved itself”; however, after this, Metr. Sergii continued to issue unilateral decisions “retiring” bishops who had been illegally repressed by the NKVD – for example, Archbishop Nikolai of Rostov in 1936. He did this without a “Metropolitan council”, which is contrary to Apostolic Canon 34. Apart from this, Bishop Nikolai himself, much like the other bishops, had not submitted written requests to Metr. Sergii to be “retired”. Moreover, the norms of canonical law do not provide for a ruling bishop to be “retired due to age”, all the more so if he does not request this personally.

In this way, in accordance with Apostolic Canon 34 and Canon 16 of the Protodeutera, Archbishop Nikolai remained the canonical ruling bishop of Rostov and Taganrog Dioceses, even after being “retired” by Metr. Sergii in 1936.

Canon 16 of the Protodeutera, cited above, was adopted by the Church in order to forestall the meddling of secular powers in the Church’s “human resource policies”. A see is not “widowed” so long as the bishop “wed” to it is alive and has not been stripped of his episcopal honor. Metr. Sergii violated this rule altogether, for example, in the above-mentioned case of Archbishop Nikolai of Rostov in 1936 or that of Metropolitan Iosif Petrovykh of Petrograd in 1927. [32]Archpriest N. Artiomov. “Novosviashchennomuchenik Iosif Petrogradskii” [New Hieromartyr Joseph of Petrograd”]. Der Bote 2/1999, p. 7–11; V. V. Antonov. “Sviashchennomuchenik mitropolit … Continue reading Can one consider such disregard for the Canons of the church, in order to appease the secular authorities, a criterion for sanctity?

The rhetoric of the public accusations leveled [33]G. I. Trofimov. “Kriticheskii podkhod k voprosu kanonizatsii Patriarkha Moskovskogo Sergiia (Stragorodskogo): po sledam Moskovskoi nauchnoi konferentsii, priurochennoi k 80-letiiu so dnia smerti … Continue reading by Metr. Sergii Stargorodskii against his fellow bishops and clergymen during the war is reminiscent of the text of his July 29, 1927, Declaration [34]Encyclical of Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergii of Nizhny Novgorod and the Provisional Patriarchal Holy Synod to the Archpastors, Pastors and all Faithful Members of the All-Russian … Continue reading which likewise contains public accusations of the Russian clergy, for example: “Many people thought that the establishment of the Soviet regime was a misunderstanding, accidental and therefore short-lived. These people had forgotten that there are no accidents for the Christian, and that in what has taken place in our country, as everywhere and always, the same right hand of God is at work, steadily leading each nation to its destined goal. To such people who do not want to understand the ‘signs of the times,’ it may seem that it is impossible to break with the former regime and even the monarchy without breaking with Orthodoxy. This attitude of certain church circles, expressed, of course, in their words and deeds, and which have aroused the suspicions of the Soviet authorities, have also hindered the efforts of His Holiness the Patriarch to establish peaceful relations between the Church and the Soviet government.”

By 1927, quite a few bishops, priests, clergy in minor orders, and laypeople of the Russian Orthodox Church had already received crowns of martyrdom for Christ’s sake at the hands of the Soviet authorities: Hieromartyr Efrem (Kuznetsov) (1918), Hieromartyr Ioann Vostorgov (1918), Martyr Nikolai Varzhanskii (1918), Hieromartyr Germogen (Dolganiov) (1918), Hieromartyr Andronik (Nikolʹskii) (1918), Hieromartyr Nikodim (Kononov) (1919), Hieromartyr Silʹvestr (Olʹshevskii) (1920), Hieromartyr Veniamin (Kazanskii) (1922), Hieromartyr Sergii (Shein) (1922), Martyr Georgii Novitskii (1922), Martyr Ioann Kovsharov (1922), and others, which was well known to Metropolitan Sergii Stargorodskii, too. Yet, nonetheless, he spoke disdainfully of the New Martyrs: “certain church circles”, publicly accusing them and declaring them to be the reason for a lack of “peaceful relations” between the Church and the theomachist “Soviet government”. But otherwise, what conclusion can one make from what Metr. Sergii Stargorodskii said as to why the “Soviet government” executed the New Martyrs? In Metr. Sergii’s opinion, they “aroused the suspicions of the Soviet authorities”… Is this a valid reason to execute bishops and clergy, or is it the morally impeccable conclusion of a holy man?

It is also alarming how easily Metropolitan Sergii’s Declaration (1927) solidarizes with the tsar-killers, proclaiming on the occasion of the killing of one of them: “…an underhanded murder like that in Warsaw [35]The assassination in Warsaw on June 7, 1927, of Peter L. Voikov (1888–1927), the Soviet ambassador to Poland and one of the Bolshevik murderers of the Czar, by Boris S. Koverda, a 19-year-old … Continue reading is a direct strike at us”. [36]Encyclical of Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergii of Nizhny Novgorod and the Provisional Patriarchal Holy Synod to the Archpastors, Pastors and all Faithful Members of the All-Russian … Continue reading He does not show any commiseration, but rather solidarizes by joining himself with the regicides using the plural pronoun “us”. Is this also a sign of “holiness” and “confessorship”?

Can we nowadays carry on serious discussions about canonizing Patr. Sergii Stargorodskii as long as the questions and misapprehensions listed above have not got full, detailed, documented, and well-argued answers?

Of course, the Soviet authorities arrested bishops and clergy even without their being denounced by Metropolitan Sergii. But Metr. Sergii’s “encyclicals” mentioned in this article had a high propaganda value for the Soviet authorities, because they were addressed to the inhabitants of those places where the Orthodox Mission was most successful during the war years: in the Northwest and in the South of the country. For this reason, the Soviet agitprop carried through the mouth of Metropolitan Sergii tried to denigrate the Orthodox clergy who had for a long time successfully provided pastoral care for Soviet citizens in the German-occupied territories (mass baptisms, church openings, the resumption of services, and the growth of religiosity among the population could all not go unnoticed by the communist authorities).

However, high and influential supporters of the canonization of Patriarch Sergii may be tempted to artificially “accelerate” the adoption of such a decision and use “administrative resources” (use their power) to do so.

For instance, the Procurator’s Office for Rostov Region resolved on August 13, 2024, to reverse its own resolution dated June 18, 1993, to rehabilitate Archpriest Viacheslav Serikov for the charges of “high treason” from Criminal Case No. П-54273 (1944–1945). Through this repeated incrimination of one of the victims of Metr. Sergii’s public denunciation, we can observe an attempt to find a moral justification for the latter using the methods of the administrative chain of command, as well as an attempt to hide documents deemed “inconvenient” for a forthcoming canonization of Patr. Sergii from the archival investigative file of Fr. Viacheslav Serikov, which has been reclassified since the decision was taken to rescind his rehabilitation.

Photograph from the OGPU surveillance file (1924–1926) of Priest Viacheslav A. Serikov (1888–1953). Supplied by local historian Anna G. Malykhina (Syktyvkar, Komi Republic). For details, cf.: M. B. Rogachev (ed.). Pokaianie: Martirolog [Repentance: A Martyrologion], Vol. 13, Pt. 2. Syktyvkar: Komi Republic Press JSC, 2019, pp. 90–91

References

| ↵1 | One can get an impression of the subject matter from my article “Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhny Novgorod as Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens to Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy” (https://www.rocorstudies.org/2020/05/09/metropolitan-sergius-of-nizhny-novgorod-as-deputy-patriarchal-locum-tenens-to-metropolitan-peter-of-krutitsa/). A whole array of bishops who were in the same conditions as Metropolitan Sergii of an authoritarian and later totalitarian state did not accept his self-determined policy. Abroad, their position was represented by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. At the same time, all of the Russian Church Abroad bishops who wound up under the zone of influence of the USSR after World War II recognized the Moscow Patriarchate headed by Metropolitan Sergii, regardless of their previous views of his policy. This fact serves to remind us that we must be very careful in our judgments. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | “V Moskve sostoialasʹ nauchnaia konferentsiia «Patriarkh Sergii i ego dukhovnoe nasledstvo»” [A Conference in Moscow on ‘Patriarch Sergii and His Spiritual Legacy’”. Moscow Patriarchate official Web site, May 16, 2024. URL: http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/6128904.html?ysclid=lwsvi58aus531010621 (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵3 | Patriarh Sergij i ego duhovnoe nasledstvo. Moscow: Moscow Patriarchate Press, 1947. |

| ↵4 | “V RPTs ne iskliuchaiut, chto Patriarkh Sergii budet kanonizirovan” [ROC Does Not Preclude Possibility of Canonizing Patriarch Sergii] RIA Novosti. April 5, 2016. URL: https://ria.ru/20160405/1402750513.html?ysclid=lwsvddp95936006820 (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵5 | A statement to this effect was made during the Parsuna program moderated by Vladimir R. Legoida on the SPAS TV channel on July 1, 2018. Arkhangelsk Diocese official Web site. URL: https://arh-eparhia.ru/news/430/74426/ (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵6 | Official site of the Moscow Patriarchate. URL: http://www.patriarchia.ru/db/text/422558.html?ysclid=lwsvpe5x35554537867 (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵7 | “O literaturnykh zabavakh” [On Literary Pastimes]. Pravda, No. 162, June 14, 1934; “O literaturnykh zabavakh”. Izvestiia TsIK SSSR i VTsIK [Bulletin of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and of the Supreme Central Executive CommitteeI], No. 137, June 14, 1934; “O literaturnykh zabavakh”. Literaturnaia gazeta [Literary Gazette] No. 75, June 14, 1934; “O literaturnykh zabavakh”. Literaturnyi Leningrad [Literary Leningrad] 27, June 14, 1934; S. S. Kuniaev. Russkii berkut: Dokumentalʹnaia povestʹ [The Russian Eagle: A Documentary Narrative]. Moscow: Nash sovremennik, 2001; V. I. Petrov. Pavel Vasilʹev. Materialy i issledovaniia. [Pavel Vasilʹev: Materials and Studies]. Omsk: Omsk State University Press. 2002; L. Kashina. “Pavel Vasilʹev. Legendy i fakty” [Pavel Vasilʹ. Legends and Facts]. Sibirskie ogni [Siberian Flames] 4, 2010. |

| ↵8 | V. D. Esakov. Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov. Stranitsy biografii [Pages from the Biography of Nikolai I. Vavilov]. RAS Institute of Russian History, Nikolai Vavilov Academic Legacy Commission. Moscow: Nauka, 2008, p. 171; Zhores Medvedev and Roi Medvedev. Vzliot i padenie T. D. Lysenko: Kto sumasshedshii? [The Rise and Fall of T. D. Lysenko: Who is the Madman?]. Moscow: Vremia. 2012. pp. 53, 59. |

| ↵9 | Kunaev, op. cit.; Petrov, op. cit.; Kashina, op. cit. |

| ↵10 | M. A. Popovskii. Delo akademika Vavilova [The Case of Academician Vavilov]. Moscow: Kniga. 1990 (1991). 304 pp.; Peter Pringle. The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin’s Persecution of One of the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Scientists. London: JR Books, 2009. p. 300. |

| ↵11 | In the Stalinist USSR, the practice of convictions and reprisals against citizens without public trial was widespread; sentences were handed down by several officers of the state security bodies (Cheka/OGPU/NKVD) in so-called Troikas or Dvoikas. |

| ↵12 | Pravoslavnaia Entsiklopediia. URL: https://www.sedmitza.ru/lib/text/439922/ (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵13 | M. V. Shkarovskii. “Mitropolit Sergii (Voskresenskii) i ego sluzhenie v Pribaltike i na Severo-Zapade v 1941–1944 gg.” [Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii and His Ministry in the Baltics and the Russian Northwest in 1941–1944]. Sankt-Peterburgskie eparkhialʹnye vedomosti [St. Petersburg Diocesan Bulletin] 26–27 (2002); Idem. O. Iliia Solovʹev. Tserkovʹ protiv bolʹshevizma. [Fr. Iliia Solovʹev. The Church Against Bolshevism] Moscow: Izdatelʹstvo obshchestvo liubitelei tserkovnoi istorii, 2013; A. V. Gerich. “Tragicheskaia sudʹba mitropolita Sergiia (Voskresenskogo): Svidetelʹstvo sootechestvennika” [The Tragic Fate of Metropolitan Sergii Voskresenskii: Testimony of a Compatriot]. Novyi Chasovoi: Russkii voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal, 15–16. Saint Petersburg: Saint Petersburg State University Press, 2004, p. 167–174; Wassilij I. Alexeev. Russian Orthodox Bishops in the Soviet Union, 1941–1953. New York: Program on the U.S.S.R., 1954, pp. 65–69. |

| ↵14 | “Sinodik Pskovskoi missii” [The Pskov Mission Synodicon]. Sankt-Peterburgskie eparkhialʹnye vedomosti, 26–27 (2002), p. 9. |

| ↵15 | Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate 9/1945, pp. 45-46; 7/1946, p. 4. |

| ↵16 | Hieromonk German Rosnianskii. “Arkhiepiskop Daniil (Nekrolog)” [Obituary: Archbishop Daniil]. Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate 11/1965, pp. 22–24; Archbishop Manuil Lemeshevskii. Russkie ierarkhi. 1893–1965 [Russian Hierarchs: 1893–1965], Vol. 3, p. 25, 26, 289; N. Griniov. “Russkaia Pravoslavnaia Tserkovʹ vo vremia Velikoi Otechestvennoi Voiny” [The Russian Orthodox Church During World War II]. Pravoslavie i Mir. May 8, 2006. URL: https://www.pravmir.ru/russkaya-pravoslavnaya-cerkov-vo-vremya-velikoj-otechestvennoj-vojny/ (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵17 | Pravoslavnaia Entsiklopediia. URL: https://www.sedmitza.ru/lib/text/439937/ (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵18 | Metr. Manuil (V. V.) Lemeshevskii. Russkie pravoslavnye ierarkhi perioda s 1893 po 1965 gg. (vkliuchitelʹno) [Russian Orthodox Hierarchs from 1893–1965]. Erlangen, 1979–1989. Vol. 5, pp. 121–125; Protopresbyter M. Polʹskii. Novye mucheniki Rossiiskie [The New Martyrs of Russia]. Moscow. 1994. Repr. (Jordanville, 1949–1957). Ch. 2. p. 120–122; A. A. Kostriukov. “Pervonachalʹnyi spisok novomuchenikov, podgotovlennyi Russkoi Zarubezhnoi Tserkovʹiu dlia kanonizatsii 1981 goda” [An Initial List of New Martyrs Prepared by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad for Canonization in 1981]. Tserkovʹ i vremia [The Church and Time] 2 (91), 2020, pp. 51—116; FSB Directorate Archive for Rostov Region. П-49273. Vol. 1. ff. 50–53v. |

| ↵19 | G. I. Trofimov. “Polkovoi batiushka” [A Priest for the Troops]. Posev 5/2022, pp. 28–35; 6/2022. pp. 34–42. |

| ↵20 | G. I. Trofimov G.I. “Protoierei Viacheslav Serikov”. Chetyrnadtsatye Konstantinovskie kraevedcheskie chteniia im. A.Koshmanova. Rostov-na-Donu: Alʹtair, 2022, pp. 422–439. |

| ↵21 | FSB Directorate Archive for Rostov Region. П-49273. Vol. 1. ff. 53, 53v, 58. |

| ↵22 | V. Koroleva. Svet radosti v mire pechali: Mitropolit Alma-Atinskii i Kazakhstanskii Iosif [The Light of Joy in a World of Grief. Metropolitan Joseph of Almata and Kazakhstan]. Moscow: Palomnik. 2004. 686 pp.; FSB Directorate Archive for Rostov Region. П-49273. |

| ↵23 | Priest F. Golikov and S. V. Fomin. Krovʹiu ubelennye: Mucheniki i ispovedniki Severo-Zapada Rossii i Pribalktiki (1940–1955) [Whitened by Blood: Martyrs and Confessors of North-western Russia and the Baltics (1940–1955)]. Moscow. 1999. p. 22, 23, 26. |

| ↵24 | Archive of the Department of the Committee of National Security of the Republic of Kazakhstan for Akmola Region, Item 3378; Central Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Fonds 1709, Series 1, Items 83, 84, 87. |

| ↵25 | Shkarovskii, “Mitropolit Sergii…”; Idem, “O. Ilia…”; Gerich, op. cit.; Alexeev, op. cit. |

| ↵26 | N. Shemetov. “Edinstvennaia vstrecha pamiati o. Nikolaia Trubetskogo” [The Sole Memorial Event for Fr. Nikolai Trubetskoi]. Vestnik russkogo khristianskogo dvizheniia [Bulletin of the Russian Christian Movement] 128 (1978), p. 250; M. V. Shkarovskii, Tserkovʹ zovet k zashchite Rodiny [The Church Summons You to Defend the Motherland]. Saint Petersburg, 2005, p. 197; Gerich, op. cit. |

| ↵27 | Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 137–138; Russian State Archive. Fonds 6991, Series 2, Item 2, f. 149. |

| ↵28 | Gerich, op. cit.; Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 138–139. |

| ↵29 | Shkarovskii, “O. Ilʹia…”, pp. 128–137. |

| ↵30 | V. V. Agenosov. Vosstavshie iz Nebytiia. Antologiia pisatelei Di-Pi i vtoroi emigratsii [Those Who Reemerged from Non-Being: An Anthology of DP and Second-emigration Russian Writers]. IRO 22. Saint Petersburg: Aleteiia, 2021, p. 7. |

| ↵31 | Alexeev, op. cit.; Idem. “Le drame de l’exarque Serge Voskresenskij et l’élection du patriarche de Moscou à la lumière des documents confidentiels allemands”. Irenikon 2/1957, pp. 189–202. |

| ↵32 | Archpriest N. Artiomov. “Novosviashchennomuchenik Iosif Petrogradskii” [New Hieromartyr Joseph of Petrograd”]. Der Bote 2/1999, p. 7–11; V. V. Antonov. “Sviashchennomuchenik mitropolit Iosif v Petrograde” [Hieromartyr Metr. Joseph in Petrograd]. Vozvrashchenie: Tserkovno-obshchestvennyi zhurnal [The Return: Church-Social Journal] 4/1993. C. 46–52. |

| ↵33 | G. I. Trofimov. “Kriticheskii podkhod k voprosu kanonizatsii Patriarkha Moskovskogo Sergiia (Stragorodskogo): po sledam Moskovskoi nauchnoi konferentsii, priurochennoi k 80-letiiu so dnia smerti ierarkha” [A Critical Approach to the Question of Canonizing Patriarch Sergii (Stargorodskii) of Moscow: In the Steps of the Moscow Conference on the Occasion of the 80th Anniversary of His Death]. Der Bote 3/2024, pp. 17–31. URL: https://www.derbote.online/ru/post/kriticheskij-podkhod-k-voprosu-kanonizacii-patriarkha-sergija (accessed January 15, 2025). |

| ↵34 | Encyclical of Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergii of Nizhny Novgorod and the Provisional Patriarchal Holy Synod to the Archpastors, Pastors and all Faithful Members of the All-Russian Orthodox Church. Bulletin of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. August 18, 1927. |

| ↵35 | The assassination in Warsaw on June 7, 1927, of Peter L. Voikov (1888–1927), the Soviet ambassador to Poland and one of the Bolshevik murderers of the Czar, by Boris S. Koverda, a 19-year-old graduate of the Vilnius Russian Gymnasium (1907–1987). For details, cf.: P. N. Paganutstsi. “Boris Safronovich Koverda”. Kadetskaia pereklichka 3/1987, p. 36. |

| ↵36 | Encyclical of Deputy Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Sergii of Nizhny Novgorod and the Provisional Patriarchal Holy Synod to the Archpastors, Pastors and all Faithful Members of the All-Russian Orthodox Church. Bulletin of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. August 18, 1927. |

Why is this being published here in “an abbreviated and revised form”? Why not just publish it as it was written before? What was abbreviated and revised, and why?