In 2021, I had been planning to visit the relics of Holy Prince Andrew of Smolensk in Pereslavl-Zalesskу for my names-day. I had even corresponded about this with Bishop Feoktist of Pereslavl. However, after February 2022, my plans did not come to fruition.

While visiting my family in Vienna in November of last year, I decided to take a trip on my patron saint’s feast day, November 9, to see Fr. Ilya Limberger in the Church of St. Nicholas in Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg. At the airport, I was met by Matushka Marjana.

She was born and raised in Belgrade, in the best years of the existence of Yugoslavia. She moved to Germany out of love and was unafraid of the new culture. As she herself explained: “I was not afraid of losing myself upon encountering a new culture for the precise reason that I had always felt I was 100% a Serb, that living in Germany would enrich us both, and I would learn something and get something out of it and, well, Germany would get something good out of me. Like a typical new acquaintance.”

In 1990, the future Matushka Marjana’s husband was ordained presbyter. Since then, Fr. Ilya Limberger has been serving at St. Nicholas Church (like my own saint, who lived as an ascetic at St. Nicholas Church in Pereslavl).

In Yugoslavia, Matushka Marjana graduated from the Belgrade Academy of Arts as a sculptor. Her thoughts on the connection between her education and iconography are as follows: “Surprising though it may be, I felt as if I would be well served by my ability to work with materials, mastery of sculpture techniques, and particular understanding of perspective and of the interaction of elements within space. In iconography, this is manifested even more prominently than in secular art. This understanding of space made it easier for me to take up iconography, that bridge between the human and Divine worlds.”

Matushka Marjana has five children, but despite all the fuss that goes with this, she has not given up iconography and continues to work. She initially studied the fundamentals of iconography in Greece, in Ormylia Holy Annunciation Convent, a metochion of the Athonite monastery of Simonos Petras. There, she learned the basic techniques and principles of iconographic thought. In the understanding that iconography cannot be comprehended simply by graduating from a course, Matushka Marjana has since studied with many master iconographers – Greek, Serbian, and Russian – and has taken something away from each one.

I was drawn in by Matushka’s discussion of icons and decided to record this interview. The ROCOR has many outstanding people, and it is important for people to know about them and their experiences. On this, our Church stands…

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev, January 23, 2025

Please tell me about your understanding of iconography.

For me, iconography is a most natural manifestation of human nature: every mother photographs each step taken by her child, and every wife holds close a photograph of her husband when he goes away on a business trip. Thus, when people ask with surprise, “What is a holy icon?” I reply that it is something most natural for every one of us.

You asked what contemporary iconography should be like. I am of the view that the iconographic canons continued to develop up until approximately the 14th century. One might say that the 14th and 15th centuries were the pinnacle of Christian culture: they were a time when deep thought was given to our customs, canons, and rules. This was a time when, in the Orthodox world, a new path was charted: an aspiration to accord great respect to beauty. Then the Baroque came along; this was a form of art that at times transcended the boundary of meaning for the sake of form. Similar tendencies came to the fore in the Christian East. There were reasons for this. By this, I do not mean to say that the Baroque is perforce excessive or tasteless. There came to be a need for a particular tenderness, soulfulness, and extraordinary beauty – and that is good. The only thing is that beauty must not become an idol but rather maintain its proper role as an aid to spiritual life.

What are our times like? We now have a different view of the world; our attention is calibrated differently. Can we paint icons in such a way that modern man can perceive them just as profoundly as people in older days perceived the icons of their time—such that the forms may well differ, yet the essence remains Orthodox?

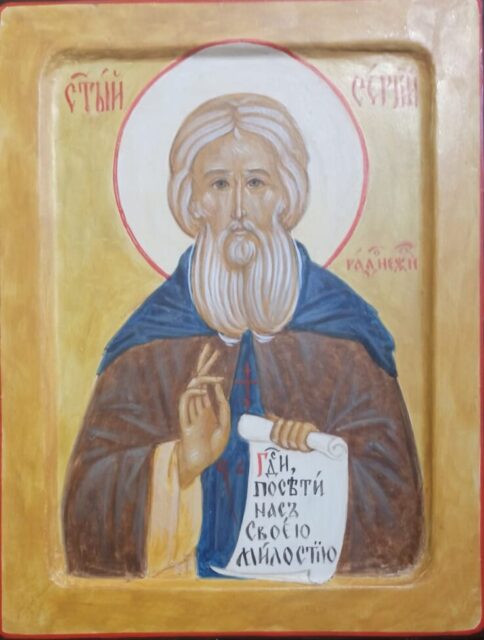

Our Venerable Fr. Sergius of Radonezh, the Abbot of Russian Lands

Nowadays, iconographers sometimes strive to return to ideal medieval specimina, for example, from the 13th – 14th centuries, and sometimes to even older images, like the Fayum Portraits. However, is there really value in simply copying, however pious it may be and however it may uphold the tradition? You know, it’s like wool socks knitted by a grandmother for her grandson or like your grandmother’s old crockery. It is all beautiful in its own way. But the best specimina of iconography were created in accordance with all the canons of art, the laws of mathematics, and the golden mean (which finds its expression even in combinations of colors). All of this reached a point of perfection 700–800 years ago. And creating exact copies of them is a proper and pious cause. But not sufficient in itself, strictly speaking.

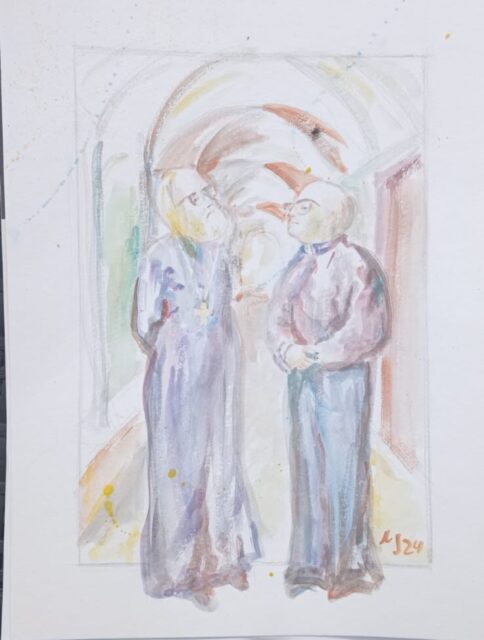

Our Venerable Mother Kassia, a Byzantine liturgical writer of the 9th c.

I fear that few iconographers now consider the similarities and differences between the past and the present. As I was already saying, our attention nowadays is dissipated: each of us has not only his or her primary form of employment but also a multitude of other affairs. This mainly concerns mothers, who previously could do several things simultaneously. It is hard to find a family where the mother does not manage everything. Now, it has become perfectly ordinary for her to have a profession and employment outside the home. It is precisely this dissipation of attention that is a distinguishing feature of our time.

Our vision has changed, too: we have electric lighting all around, we read not off of paper, but rather from the screens of telephones. And political life has become fiercer, so we not only have to keep up our traditional way of life, but also take a stance on the environment, culture, bioethics…

Yesterday, you said that when you look at St. Andrei Rublev’s icons, you see people…

…as they were praying back then. Yes, right.

And it is as if you see what he saw. I was struck by your thought that an icon is a reflection of the iconographer’s time.

Yes. I can take this thought further. Take, for example, the time of St. Andrei Rublev. When looking at his icons, you can understand the personality of the people whom he saw praying before him. I spoke about the personality of the people who stand at prayer nowadays. Now, about the icons. Medieval artworks enable us to make surmises not only about the psychology of those people, but also even about their outward appearance. The icons enable us to see what the people were like who would pray in front of them.

Our venerable mother, Petka-Paraskeva, a Serbian ascetic of 11th c.

In this interview, I would like to emphasize the difference between us and people back then. Some iconographers strive not only to copy ancient images, but to construct a dialogue between the saint, the icon, and modern man. I think that icons ought to become somewhat simpler so that it is easier for us to pray before them. At the same time, it’s important to find a special measure in the facial expression: not overly strict, but also not excessively mild, either. For a modern person, the gaze ought to be different than for people from past centuries.

Thank you. If I understand correctly, you acknowledge the need for an iconographic canon, but leave room for creative reflection. You would not simply copy medieval templates – for example, Our Savior “of the Burning Eye” (yaroe oko), where the Savior has a very penetrating stare. Your works combine canon and creativity.

Yes. An iconographer is obliged to be a craftsman. As with any craftsman, much here depends on experience and intuition, which are developed over many years. Of course, any tradesman is helped by talent, which is given by God in the form of love.

If a person is genuinely interested in a particular thing, this is practically equivalent to talent. For example, I love to sing, but singing is not my thing at all. So, interest does not always overlap with one’s gifts. But I was always able to draw, if not brilliantly. Talent, intuition, and experience: these things help us understand what we lack if we merely copy ancient icons, what must be added, and what must be taken away.

Of course, the canon of an icon is the very foundation, and about this there can be no dispute. What has been established by the Councils of the Church is unshakable. But in the perception of a particular icon, there is room for variation: the contrast between colors can be strengthened or softened, the palette can be broadened or narrowed, a saint’s gaze can be made stricter or milder. It is precisely in this that our experience is important because our craft informs us what alterations are required for an icon to be correct so that a person at prayer can immediately sense a connection with it and feel that he or she is conversing with the saint or partaking of the feast. In essence, the language of iconography becomes more appropriate to the time at hand in the same as any language changes over time.

Thank you, Matushka. There is much food for thought here.

Related Articles

Archpriest Ilya Limberger, On Working With Young People And Why The Church Must Engage With Society.

Archpriest Ilya Limberger, Archpriest Ilya Limberger On Social Ministry, Overall and in a Given Parish.