The appearance of the Russian Church Abroad is linked to the Revolution and the Civil War. The nucleus of the Russian Church Abroad consisted of political immigrants. Finding themselves “on the waters of Babylon,” they were thinking not only of why they had lost Russia, but also of its future structure.

In 1921, the All-Diaspora Church Council was held in Sremski Karlovci with representatives of Russian refugee communities in Europe. Hierarchs, clergy, and laity expressed in a Council resolution their view on restoring the Romanov Dynasty in Russia as an act of repentance before God. In this way, in the ROCOR, Monarchist views came to have the status not of political convictions, but of part of the Orthodox worldview.

In the conditions of the great trauma of the Civil War and the Revolution, those who ended up in the emigration as teenagers and those who grew up here regarded the fight for Russia as the main purpose of their lives. The National Union of the new generation, created in 1930, was supposed to leave behind the errors of their fathers who had not preserved Russia from the catastrophe and to begin the country’s rebirth from a “blank page.”

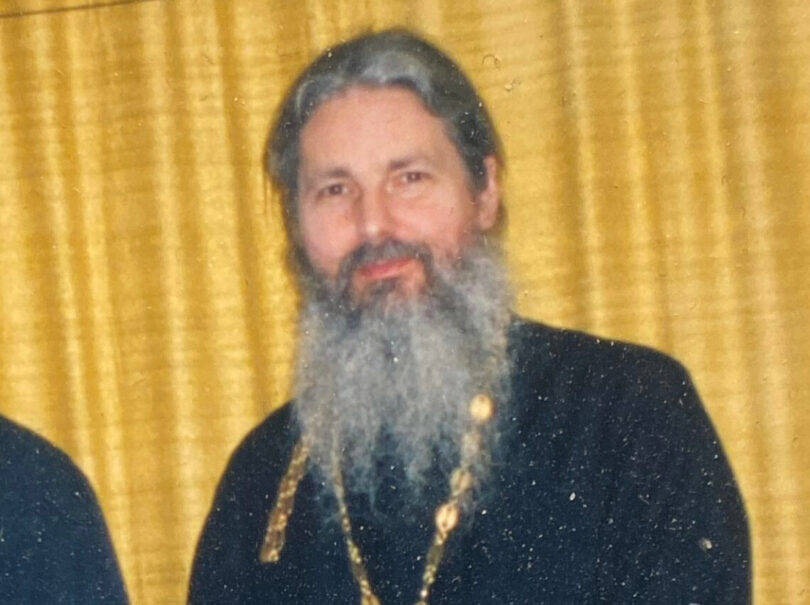

An encounter between those wishing to fight for Russia was occurring within this organization: The People’s Labor Union (NTS in Russian), without any segregation between the “Soviet-born’ and the “Diaspora-born.” The Mitred Archpriest Nikolai Artemov grew up in the family of the NTS’s chairman Alexander Nikolaevich Artemov (1972-1984), who during World War II was a Soviet prisoner of war in Germany.

For this interview, I have borrowed the title of Dr. John Dunlop’s (d. 2023) book The New Russian Revolutionaries (Belmont, MA:1976), in which he writes about the USSR founders of the All-Russian Social-Christian Union for the Liberation of the People, Yevgenii Vagin and Igor Ogurtsov.

For readers of ROCOR Studies, this interview is of interest in that it shows how, in the ROCOR, not only Monarchist views had the “right to exist.”

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev

Vienna, November 22, 2024

“It looks like we have jumped out of the frying pan into the fire”

The Civil War ended, and people had ended up in the emigration. They were trying to figure out how to continue the struggle for Russia. Many different organizations were created in the interwar period. The first emigre generation appeared. And so, the National Union of the New Generation. It appeared in Belgrade, didn’t it? And then the war came, and there was an attempt to use the situation and go into Russia. An encounter with Russia took place. And already after the war, as I can judge from Posev, the NTS was very well informed. I am not sure that there was any open periodical in Russian at all in which what was taking place in the Soviet Union was reflected so precisely. And for myself, living in the emigration, I have noted over much of my life that when I find out that a person had been in the NTS, for me this means a mark of destinction. Immigrants connected with the NTS are better informed and broad minded. That was my first perception of the NTS with which I arrived at Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville in 1990.

I think that some sort of experience should be specified here. You just mentioned that this began somewhere in Belgrade. I knew a person who was responsible for a closed system. A “closed system” denotes contacts with Russia. But he had been in the White Movement when quite young and then ended up in Yugoslavia. Georgii Sergeevich Okalovich was his name. He was an amazing person who was trained as an electrician. And at one point he told me his story. Unfortunately, those tapes disappeared somewhere in the archives. But I remember his stories very well. So, there was the Civil War in his young days. And then the most interesting thing happened. He went to Russia in 1937, getting through the Iron Curtain. He described an incredibly tall pile of windfallen trees, so if you tried making your way through there the snapping of twigs could be heard all over the forest. He hid his weapons someplace there later, and they started searching for him. As he walked, he saw the situation — it was foggy, the peasants were roused, and they combed the forest, and he also rose from the bushes and made noise, falling back, falling back, and ended up disappearing. They did not find him. He came to Petersburg, which was then Leningrad. His sister lived there, and he paid her a visit. She said to him, “George, why did you come here? In two or three hours, I will go to the NKVD and tell them that you came here.”

After that, he still remained under search warrant. He was there for three months (I’m not sure of that is accurate, maybe it was longer). He worked and had a workbook, and he returned with that workbook through the windfallen trees and other barriers, crossing the Polish border to tell us everything that happened. And there was another experience like that.

Why, my family had many members in the NTS, beginning with my uncle, Roman Nikolaevich Redlich, my mother’s older brother, and, of course, my mother. My father was among the leadership still during the war. So were my aunts and uncles in Australia. Zezin, my aunt Vera’s husband, and George Bonafide, my Aunt Natalia’s husband, also in Australia. So this was all a sort of a family business, you could say. And what happened to them? They came to Germany in October of1933. You can now read about this in the book Vospominaniia solovetskikh uznikov [Reminiscences of the Solovki Prisoners], when my grandfather was imprisoned at the Special Purpose Solovki Camp This does not mean that he was at the actual monastery. That was a huge territory. And at some point we managed to publish my grandmother’s reminiscences, where my sister and I, along with our cousin Redlich, wrote how they reacted to my grandmother, who went there, to Solovki. And these reminiscences were published.

Did she go from abroad?

No, she went to Solovki. My grandfather was incarcerated in 1929. The how and why of this is described a little. First, when the Soviet government was established, he had to sign a statement that as a manufacturer he would not engage in anything capitalistic. Then, when the New Economic Policy came, he was forced to engage in it under threat of execution, even though he had signed the statement that he would not do so. And then it was 1929 and the first five-year plan, and he was imprisoned. Poor man. And so, she visited him with the help of Ekaterina Peshkova. She was able to do that.

Through the Red Cross?

The Red Cross and also the Committee to Aid Political Prisoners. Such things happened. She managed to obtain permission to contact her parents, who were already in Berlin through the Kreenholm Manufacturing Company in the Baltic Lands. These were wealthy people. They paid the ransom for the entire family — my grandfather, grandmother, and seven children, who filled up the ranks in large numbers. The NTS was already in existence, but they joined it later. It was such a family business. More than that, [they were people with] experience of the Soviet Union arriving in Berlin in 1933. But I wrote there that my grandfather watched the torch bearing-processions by the SA storm troopers out of his window.

So, these youngsters came to Berlin. There were seven of them of different ages. My mother was sixteen. She experienced this arrest and had various experiences in the Soviet Union itself, and her older brothers had even more.

Was your mother born in 1913?

She was born in 1916. She was arrested in Russia in 1933. And by then, you could say, they had been resettled. Conditions were very difficult. There’s a book about that as well. It also mentions the Prove merchant dynasty, something I’ve forgotten. I can give a reference. When they came to the hotel, my grandfather saw those Nazi parades in Berlin at the end of 1933. He was looking out the window and saying, “Asya, it looks like we have jumped from the frying pan into the fire.” This means that the family, and this is in the reminiscences, was preparing to flee. They had reference letters for the German consulate in Iran. You will remember that Fr. Michael Polsky fled to Iran.

So their oppositional experience was also unique. And if you read the book, you’ll see that back in Russia, Roman Nikolaevich Redlich had pledged to serve Russia and to fight that regime. When he came here to the West, they naturally somehow made contact there. And here is another story, concerning Alexander Trushnovich, who was killed in 1954 in Berlin. He died in the car when he having been kidnapped was being transported from Poland into Russia. He had incredible strength and was Slovenian. He fought at first on the side of Austria but changed sides as a Slovenian. He changed sides actively, as part of a whole group that did so out of patriotic or pro-Slavic considerations.

His reminiscences have also been published, as part of the reminiscences of those in Kornilov’s Army. He was a doctor and managed to conceal his participation in the White Army, continuing to work as a doctor in the Soviet Union. Zinaida Nikanorovna, his wife, was a nurse, that’s how it turned out, and I knew her as well. I knew him theoretically, but I don’t remember him. He treated me when I was very little, and it was thanks to him that I stayed alive. There were big problems with my delivery, and he happened to ask, “How is Asya doing?” When they realized that it was a placenta previa and that both the mother and I could die, a cesarean section was performed and everything turned out to be fine. I was alive from then on.

Did he take part in this?

No, he simply diagnosed the problem and rushed my mother to the hospital. That was in 1950. Later he treated my hernia. And then he was grabbed and taken by car, and he died there. Yaroslav Alexandrovich, his son, obtained access to his case file in the nineties and found out where he was buried in a Polish forest. He received his cap, notebook, and some kind of watch from a drawer of the KGB or MGB of the time. And so, he had lived as a doctor in the twenties and the early thirties. He was allowed to leave in 1934 as a Yugoslav citizen. In Belgrade, he got in touch with the NTS. And Yaroslav Alexandrovich, his son, lived his entire life with the NTS. And also, going further, about seven million or more came here to Germany [during the Second World War] from the Soviet Union, and they were being squeezed more and more. For Kiev was evacuated forcefully [by the Germans]. And people would go away. And a huge amount of people converged on Germany. More than half of them were repatriated [after the war] voluntarily or involuntarily. This was also described by many. These were all Soviet citizens. There were those who had survived collectivization and many others. They came to their own conclusions. Take my father, for instance. He was a Komsomol member and took part in collectivization at the outset. But later he saw what form this had taken on and gave back his Komsomol membership card. In general, a lot could be said about Papa. He would laugh later. I told him that I don’t get it, you’re an honest man, after all. “I don’t understand,” he said, “how they hadn’t noticed me later, since around ‘30 or ‘31 I took this oppositional step of leaving the Komsomol.” But later he was an officer in Khabarovsk and returned to Moscow, becoming a post-graduate student at Moscow University. And after that he was at the front. When he became a German prisoner of war, my mother’s brother got him out of the camp as a specialist, since he was a microbiologist working on brewing bacteria among others. And so Papa told this to Roman Nikolaevich in some conversation. This was Dr. Roman Redlich, who had graduated in Philosophy at Berlin University and was fluent in German from childhood. And at the same time, he was a member of this organization, NTS, which was banned in Germany and operated underground. This underground organization brought together its sympathizers, including those in the prisoner-of-war camps. And what was interesting was that the prisoner-of-war barracks contained officers of the Russian Army, the Soviet Army. For the first time after the Stalin horrors, the fear of everything, since there were informers everywhere, were they able to speak openly of their political vision, of the way they perceived Russia. And, of course, they had various opinions. Some said that Hitler should be done away with, while others said that Stalin had to go first, since the Germans had no chance. And this is a very interesting phenomenon, a contemporary one. In Russia people don’t get it. They keep saying that if the Germans would have won, there would have been such a horror, a Nazi one. But we can read about the opinions of people during the first and second years of the war. Kirill Mikhailovich Alexandrov wrote a book titled Pod Nemtsami [Under the Germans], containing accounts by partisans. There are totally amazing facts that are also found in the archives saying that the Germans lacked any sensible program and quickly took everything over, as their military installed Communists in the provinces, since they were managers and could figure out what to do. So that is what happened. And the partisans were writing that we had no chance. So as a result, Stalin issued a directive for partisans to cause harm to the population. That was so that the Germans would be provoked to inflict blows on its own population, and in the context of this kind of retribution the Russian population would still be stronger in its resistance to the Germans. Initially, the military behaved decently. Later on, the situation got worse and worse. You see? Russians who were convinced that Russia must be without the Germans and without the Bolsheviks got on the bandwagon. This was the so-called “third way”. And then Georgii Sergeevich Okalovich turned up in Smolensk. You can also look at the reminiscences of the mayor of Smolensk to see what the situation was like. These people had the opportunity to socialize with the population of Russia at various levels. I know Ariadna Evgenievna Shirinkina, since I worked with her in the NTS. She was imprisoned by the Gestapo. It’s simply miraculous that she stayed alive. How many of the NTS members were done away with by the Nazis? Wikipedia says that there were about 150. I cannot check that, and I haven’t heard it, either. This was during wartime, which ended with forceful extraditions. That was a huge, bloody tragedy for Russian people. But the Church, which has special interest for you, rewrote people’s baptismal certificates, since, according to the Yalta Treaty, all Soviet citizens who were living in the Soviet Union in 1939 had to be extradited. Again, let me return to my father. I have his baptismal certificate, containing a seal and printed faultlessly on old paper. Later, I found out how this was done. It needs to be dipped into tea and ironed, to look old. There is a seal, an indication that he was supposedly born in Harbin, and his last name being Artemov. His actual last name is Zaitsev. So I am essentially a Zaitsev. Why Artemov? Because my great-grandfather, a cooper in Rostov-on-Don, came to Turnovo to buy oak, but fell in love there by the Oka River and stayed there. And my father, when he had to decide what last name to take, decided to use Artyom from Rostov. And so, he settled on Artemov. My mother was a secretary who could type with her eyes shut. And there they were, changing people’s baptismal certificates. In come the simplest peasants, wearing something like bast shoes. And they say, “Well, young lady. What do we do now? They’re saying that the NKVD has been disbanded, our motherland has forgiven us, and so on.” She asked them, “What’s your name”? “Artemov,” he said. She turned and yelled, “Sania (nickname for Alexander – ed.), come over here and take a look at some real Artemovs. Maybe we should make Zaitsevs out of them.” Just try to prove that you’re not a camel. This involved hundreds of people. I know of five hundred people in one camp who were transformed into Poles in one night. But wasn’t this connected with Vladyka Vitaly (Ustinov)? And then there was Vladyka Nathanael. I know that story. Yaroslav Alexandrovich was a young man. Vladyka Nathanael emigrated. But his father had been Ober-Procurator and tried to crush the All-Russian Council.

He was a Renovationist later.

Vladimir, I believe. And Vladyka Nathanael, his son, who was young and sufficiently energetic, and knew languages, etc. He had been given a car which had a Russian tricolor flag on the right side and a British flag on the left. When they came to that camp, it was already shut down. He somehow managed to obtain permission for those people to stay there. And Yaroslav Alexandrovich was at the wheel, and turning around, asked, “Father, will you bless me to ram the gate”? Vladyka had a slight special burr in his speech and said, “Ram in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” He burst through the gate in that car. People were already being loaded, so Vladyka Nathanael ran out, imagine this, bearded and with long hair (he was an archimandrite then), and yelled, “You don’t have to go, you can stay!” People were dumbfounded, not getting what was taking place. He understood that something had to be done. And so he grabbed the first person, yelling, “Get away, away from the truck”! These are legendary stories that were told to me by people who took part in them. At one point he came to such a camp, and the whole camp got on its knees in gratitude for being able to stay. For they had been deceived to the full. Then, if we take Lienz, for example, (where Cossacks who had been in German service and their families were handed over to the USSR – ed.), we find an incredible and also a very amazing story. The book Eto my, Gospodi pred toboiu [This is Us, O Lord, Before You] can be found on the internet. It was written by Evgeniya Polsky. She was a reporter and could have stayed. But her husband was one of the Lienz officers and they were both deceived, taken back to Russia and handed over to the NKVD.

I don’t understand; these were, after all, German military men, wearing German uniforms, so they were collaborators.

Everything can be mulled over and then decided upon, sized up. Especially since people were with their families. Let me finish with Polsky. How things happened with those people. Eventually, conversations ceased in the barracks, since spies would be planted there. And there was a change in the atmosphere. I know of a case when a person escaped from Dachau, but his coat was shot through, and he was brought back right away. He was young and worked for some peasants, or Bauern, as the Germans call them. So they would go around to various places. He would deliver milk. Then, right after the war, he was screened, and it turned out that two of those that were with him in that place had these light blue stubs, which meant that they were in the NKVD, or however they were called there.

In a German concentration camp?

In a German concentration camp. And they told him, “You’re a good guy, we know you. You can go, everything is okay. Just don’t live in the same place for longer than three years.”

In Russia?

Yes, in Russia. Change your place of residence. Whatever I heard, I sell. Let us return to Evgeniya Polsky. She could have stayed but decided to follow her husband. That is described in a staggering manner. She went in that train car. We know how they were treated. That train, which was en route to Russia, stopped somewhere in Hungary. She got up, looked out the barred window and saw piles of executed people. And suddenly she thought that her husband could be among them. So where am I going, she thought, and what for? So she reached Russia, was put into a labor camp, did her time, and found her husband. They reunited and wrote this book. Returning to the NTS… These were people who in one way or another went through this experience and believed that the regime had to be changed in Russia.

“If we show them that we are afraid, they will do this”

And they were, in general, all offshoots of the Russian Church Abroad. We have the situation that the NTS appears as if it is within the Russian Church Abroad. The parish in Frankfurt appears to be an NTS parish created by Solidarists. So it appears as if the Church was a part of NTS. Father George Grabbe, somewhere in his correspondence, I believe, pays special attention to West Berlin, because it has a special status in determining who will serve there. I don’t know if the Americans took some part in this as well. On one hand, there are Monarchists in New York, while Solidarists are in Germany on the other hand.

And that same Bishop Gregory Grabbe, who was then Father George Grabbe, wrote some horrifying things about NTS members. I read that everything there was corrupted by masonry. Yes, he had a very radical view. And when I read this, I was somewhat disheartened. That was long ago, of course. There actually were people who were less churched, since a bit of a Soviet spirit remained in those who had been raised with atheism. They had a certain caution toward the Church as an organization. But there were also people who were very church-oriented. And they were active in this respect. The NTS philosophy, its doctrine, are actually based on the Church’s social doctrine. You could place it alongside the NTS program and find that there is perfect compatibility between them. Monarchism, the monarchy, were not rejected. There were differing viewpoints on this subject. But in the final analysis this was accepted. Later, I accepted all that when I became an NTS member. I started investigating what this Solidarism was. It was varied. There were French roots, but also German ones. These German roots are essentially Christian democracy. That is nothing new. Even the Christian Democrats, the CDU, have a Solidarist ideology. Mikhail Nazarov and I visited the famous economist and sociologist Oswald Nell-Bruening in Offenbach, outside Frankfurt and interviewed him. He was ninety years old. His teaching is that of the national economist Heinrich Pesch. He wrote a five-volume work on the national economy, Lehrbuch der Nationalokonomie. There were other both economists and sociologists such as Gustav Kuntliach. There were others, In general, it was a sufficiently contemporary doctrine for that period. As an NTS member, my father was involved in training officers for the Russian Liberation Army. He based his teaching on Berdyaev, Ilyin, and Frank. Semyon Ludvigovich Frank published Dukhovnyia Osnovaniia Obshchestva [The Spiritual Foundations of Society] around 1930. And then there was Nikolai Onufrievich Lossky. He would visit us at home. He was a philosopher, and I recall him publishing his books in Posev. And his two sons are theologians in Paris.[1] Paris is just an arm’s length away from us. So this émigré can of worms has, on one hand, its rough edges, and in spots on the inside there is terrible opposition in a political sense and even in an ecclesiastical one. You can take Paris and Evlogy and Metroplitan Anthony Khrapovitsky, along with Vladyka Anastassy, and here you have this jurisdictional opposition. But on the other hand, all this is not so simple and is greatly mixed up. It was not without reason that Evlogy and Anthony reconciled in 1935. Then Vladyka Evlogy was pushed aside and later he took a Soviet passport that Bogomolov handed him in Paris. This is a fascinating story.

But this gave the reconciliation of 1935, which was what preached Christ to those of the second immigration rather than jurisdictions, to make it easier on them. If this hadn’t happened… Why, ROCOR announced in 1926 that Evlogian sacraments were graceless. For Father Kiprian (Pyzhov), who was in Nice, the first encounter with ROCOR clergy was when the Kursk Root icon was brought there. Father Alexander Elchaninov, his spiritual father, approached the icon. And who was from ROCOR with the icon? A similarly venerable archpriest, who said, “Father Alexander, remove your epitrachelion” (he was in Metroplitan Evlogy’s jurisdiction).

These are bitter things. Some of that is happening now. We can see the extent to which bitter things can exist in what is happening with Ukraine.

Choices, choices. During the war there were choices: to stay there, join the Germans, or oppose them. What to do? Now, it’s also a matter of choice, such are the times. How will I do this, who will I be?

You’re between a rock and a hard place. Why, Russians were completely abandoned then. But, returning to the political aspect of the NTS, what did logic dictate even before the ’90s? I’m jumping to the late ’80s, to Perestroika. Who makes an appearance? It’s the Christian Democrats: Victor Akshutits, Gleb Onishchenko, Valerii Senderov. He simply chose the NTS. And I recall that on November 4, 1972, there was a Posev conference when Yura Galanskov died in the Perm Labor Camp 17A. How could we be not interested in that? How could we live here in the West and not seek contact? Take Boris Georgievich Miller. I lived with him and worked for the NTS in London. He came from a Serbian immigrant background and later died in Russia. He told me of his first encounter with seamen in Sweden in the ’50s. And so, Boris Georgievich asked him, “What would you like? We can go and have a talk.” And he said, “I’d like a banana and Coca-Cola.” And once he tried that Coca-Cola his eyes grew wide with amazement. For horrible things were written in the Soviet Union about Coca-Cola. He said, “What kind of syrup is this? This is some sort of nonsense.” I had experiences like that myself. There were even cases that I cannot talk about. There we were in Rotterdam with seamen, walking the streets and handing out literature. Sometimes we managed to wander into a restaurant for a nice discussion. This was already a sign of great trust. And there were different kinds of people. There was an occasion when a political assistant was sitting and smoking with ten sailors. And they knew that we were there. Someone decided, or got a directive, to start an argument. And I remember that we were sitting there and arguing. He was arguing while the others listened. At a certain point I said to him, “You are presenting good arguments, but people think with their own brains. Why have you avoided mentioning this and that?” I was a student of Western European history then, so I was able to bring up certain things about the Second World War. And people were interested. I would generally not be able to speak Russian anymore if I did not have outside contact with people who come from Russia. There was this interest. And the other side of this activity, one that is more apparent, is the press. This involved getting information from the Soviet Union and sending information back into the Soviet Union. I perused in my childhood – I didn’t read very deeply, just lying there on my belly. A man named Svetlanin lived in the apartment next door. His real name was Nikolai Likhachyov, but Andrei Vasilievich Svetlanin. A heavy smoker, he had stacks of Soviet newspapers piled up on his table, with Krokodil[2] among them. Besides Mickey Mouse, I read many Krokodils in my childhood. And I remember them having sideways pitchforks. These were tridents, and that is an NTS symbol. And then, suddenly that trident changed into a quadrident. They noticed such trivialities. And so, Andrei Vasilievich, when something would take place. And that was 1962… Solzhenitsyn wrote about this later, how children would fall from trees when there was shooting into the air. There was an insurrection and a strike in Novocherkassk.

Andrei Vasilievich read in the Soviet newspapers that something was being done over there or that they got some kind of construction – I don’t know. Was it a triumphal arch or something of the kind? He said that it was a tank. Only a tank could cause that damage. So this means that tanks were there? Such things were literally scrutinized with a magnifying glass, and that is why Posev was able to write about an atomic explosion and a catastrophe in the Urals in 1957. How it happened was explained. I taught Esperanto and met with many Esperantists outside the Soviet Union as well as with chess players. We would catch everyone we could. We were here, and Natasha [Fr. Nikolai’ wife] was here, too. I was also in Munich at the Olympics. There were most interesting encounters with athletes and tourists. I can tell about this separately elsewhere. Youth work followed this direction as well. Of course, I was in the tightest and closest circle. But there was interest in the Russian Scouts aborad as well. Of course, we could say it was infiltration. Efforts were made everywhere, wherever possible. You simply lived in this milieu. Naturally, I was in the Scouts. And later, when I left the Scouts, I joined the NTS. And when I became a priest, I naturally would have left the NTS. When the issue of becoming a priest arose, I was simply told that there are lower and higher forms of service, and that I had been drawn to the higher one.

At the NTS, my leadership told me that there is a higher form of service and that they, of course, respect pastoral care. If this appeals to you, then be my guest. We went on a pilgrimage. After that, two or three months later, we moved in with the present Vladyka Mark, who, of course, was also familiar with the NTS. But what was actually the case? I already told you about Alexander Rudolfovich Trushnovich, who was murdered. Around that time Nikolai Evgenievich Khokhlov came to kill Georgii Sergeevich Okalovich. I also met him many times later in my youth.

He had read everything that he could have read in Moscow State Library about the NTS. And he reached the conclusion, including under his wife’s influence, that he didn’t want to do the killing. But how could he avoid doing this? Of course, there were rules forbidding one-on-one encounters in those days. The German agents had to bring a weapon made by Sudoplatov. There were poisoned bullets, shot out of a cigarette package, that were designed especially to kill Okalovich. There is a book about this entitled Pravo na sovest’ [The Right to Conscience]. I don’t know if it’s available on the Internet, but Posev published it. Khokhlov is the author. Of course, it was edited there. And so Georgii Sergeevich was alone in his apartment, and Khokhlov rang his bell and said, “Georgii Sergeevich, I have come with a problem. I have a task to kill you, but I don’t want to do this. I need to speak with you.” I know Georgii Sergeevich. I was a priest when the current archbishop performed extreme unction as he was dying. After that he got up and lived for another five years. I remember the hospital where that happened. Close contacts with these people could be discussed for hours. Georgii Sergeevich resolved to speak with them. They figured out what could be done and what couldn’t. It’s a very interesting story. Of course, the “Central Organization of Political Emigrants” was present there. After the War, the Americans were trying to unite these anti-Soviet émigrés.

It is also clear that all this information was used by the Central Intelligence Agency?

I know for certain of an encounter in which my godfather, Evgenii Romanovich Ostrovsky, and my mother’s brother, Roman Nikolaevich, took part.

Roman Nikolaevich, Redlich, and my father, Alexander Nikolaevich Artemov, were involved. And they were offered money [by CIA personnel]. At one point, Roman Nikolaevich made a statement that we would not do anything against Russia, and that we do not accept such tasks. Then they decided to leave, since the conversation was becoming pointless. One of the Americans said, “If you remain without any funds, you won’t be able to do anything. You are wrong.” “Without funds we would be able to do less. But without Russia and the Russians we will be able to do nothing.”

They were presenting certain demands and conditions which were unacceptable. And then the NTS, its leadership, said, “No, we are leaving, we don’t need this.” They got up and started leaving. And then the Americans said, “Wait, wait.” This was taking place at the Frankfurt train station, and the CIA headquarters were next door. But there are also overlapping interests. One of these examples is literature. The Americans would buy up much of a press run, while the press run of Kirill Elchaninov’s[1]I have mentioned his father, Prot. Alexander Elchaninov, here. Kirill headed the L’aide aux

croyants organisation that helped believers in Russia. –P.А. books were distributed for free among the entire diaspora. And the Esperantists, chess players, sportsmen, and seamen would come again. If I, as an émigré, have any number of copies of GULAG on my shelf, I know that Elchaninov will send me more copies when I hand all of them out. Then the system works. What is this? It is not a spying organization, or the creation of a network. This is how we work in our interests. If this is for some reason interesting to them [the CIA], we are ready to work with them. For instance, I was with Radio Liberty, which has deteriorated badly by now. It is simply terrible. It was not like this when Evgenii Ivanovich Garanin was there, who actual last name was Sinitsin. That was when it still had Russian interests in mind. And I was invited to appear there and deliver daily sermons. This was called “Approaching the Day.” These were spiritual discussions. Whether they were good or bad is another question. I was young then. But I do not see that in this context I need to repent of working for the CIA. But where were the funds for the station coming from? Do you understand? This was all very comprehensive. Things change, and with time they change in a big way. And the NTS itself changed, of course, and therefore it fell apart in the final analysis.

It came to nothing. Nonetheless, what was done was still probably done in the proper key. I don’t know what has remained of Christian Democracy in Russia, and where it has gone and where it will yet go. This is totally unintelligible. But then, when I was small, there was Khokhlov. We knew about that in principle. And when I was a boy, an explosion happened there, in Sprendlingen in 1958. The Pavlovs were living in that house. My old friend Lyonya told me that it hit suddenly at night, and he could see the sky and the stars. Half of the building collapsed, and he moved off his bed, which went into the abyss. He fell over and crawled back out of his room. I saw that building. And then Mikhai Leonidovich Olsky had to gather all the mothers, because we were still boys and girls. My grandmother taught grammar to these émigré children. She taught history, literature, and grammar. So all these mothers were gathered, and Mikhail Leonidovich said, “These are dangerous times, so you need to accompany your children to school and back.” And my mother said, “Mikhail Leonidovich, if we show them that we’re afraid, they will do this.” I am a father myself, I have grandchildren, and it is hard for me to understand this. But I know that I walked around Frankfurt to school as a six-year-old and crossed streets with columns of American trucks going by. They smelled awful. I was little, and the exhaust pipes were high up on these huge trucks with a white star. I would cross the street to where my school was, the elementary grades. That is the reality in which these people lived. I was not there; I was in a children’s camp. And over there, where we played soccer in 1961, in August, I think – the Berlin Wall was built in 1961 – a bomb was thrown. We had a Nikolai, whose last name I forgot. He was lucky, since he had bent down to light a cigarette. When the bomb went off, shards of glass were flying all over. And then anonymous letters started coming to our landlord telling him to kick out Andrei Vasilievich, Evgenii Romanovich Ostrovsky, and those vile Artemovs. We occupied three apartments there along the inner hallway. Get rid of them, or else the next bomb will be for you. And that unfortunate German, – a Nazi, by the way, named Alfred Leiza – tried to evict us, but the court took our side. Only thanks to the court did we stay. After that bomb, we were told that the publishing house had to move outside the city limits. That is why Posev was at Merlinstraße 24A but was moved from there after the explosion. We also got help to acquire property there. That house is still standing in Sachsenheim.

All that was there was a vacant lot. We were given the vacant lot, which was probably sold at a great discount. I recall that there was voluntary rate-paying, but half of the lot was later taken away. We got money for this. And then we started building that house. And then there was also Grani, for example. That is a cultural magazine and a project in the German Cultural Ministry. Some funds were received.

The German Cultural Ministry – these are the networks I meant. But when that house was being built we boys were drilled by Georgii Sergeevich Okalovich. I remember the batteries hurting my hands, because we were plastering without covering the batteries, and we had to clean off the plaster with iron brushes and then paint them.

Georgii Sergeevich was in charge there, and we were there. We were paid a little and we cleaned there. It was freezing, and I recalled Shukhov a bit. I read One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich then.

And during that period, when the construction was still not completed, this ticking suitcase appeared. My mother asked Georgii Sergeevich, who was an electrician, about it, and he made it harmless. So she asked him, “Do you know how these bombs work”? He replied, “No, not strictly speaking, but I did have some idea. What if I waited for the police to come and it would explode?” But he did open that suitcase! He was ready to do such a thing.

You mean that he had already died in a general sense.

Now this was a truly believing Orthodox Christian. In Schadeck, where we were first living as refugees… That was in ’51 or ’52. I was born there in ’50. So a car pulled up to his wife and they started taking her right in the street. But they didn’t succeed, since people were present somewhere around there and she beat them off. And our elderly landlord Schlosser later said to my parents, “I have an axe under my bed. If anyone comes into the back rooms where you live I will defend you.” And he was a German. There was another bomb in ’63. That was our cheerful émigré life.

Which one exploded, the second one?

No, they threw the first one over the fence in 1961, but it did not go far enough. It exploded in the yard where we boys would play soccer. That was at night. They stole through the yard of the house on the next street over.

It was seen by Nikolai, who was the guard there. He had bent over to light a cigarette, and, luckily, the glass flew past him. Later, it got windy there and my father tried to shield himself with curtains. He even became disabled, but only due to his ineptitude, since he got up on a chair to try and secure the curtains. That chair moved, and he fell and hurt his Ieg. You could say that he became an invalid due to a Soviet attack. But I do remember that crater, which was covered with cement. And I am not quite certain about what happened afterwards. I am certain that the Pavlovs had Krym. That was a terrifying dog who was silent, but could tear you to pieces. And then Lord appeared. He was a barker, so was probably less effective. That was our defense, which was greatly increased after that bomb. And, of course, there was barbed wire, and no more playing soccer, since Lord was running around there. There was Poremsky’s son, Alexei Vladimirovich Poremsky. I knew him from childhood. His wife Olga, a priest’s daughter, is still alive. He was 25 or 26, and Olga 21 or 22. All the evidence shows that the matter was hushed up over there, but that is impossible to prove. When he was turning onto Zeppelin [straße] in his motorcycle, the steering wheel broke down and he fell off, smashing his head, possibly against a lamppost. When she saw him in the emergency room, he recognized her and died. This was not particularly harped upon, but it still was a fact. I also saw that motorcycle. There was also a fellow who attended the same school with my cousin and the future Metropolitan Mark, which was the Helmholtzschule. That was a high school, and Igor Cherezov was a pupil there. His father was in the NTS and was kidnapped and taken to Russia. Postcards came from there, saying everything is fine, so come on over. But what is the meaning of “everything is fine, come on over”? A phrase was included there (I don’t recall the exact words) to the effect that he was sorry that Osta wasn’t with him. And I always saw Osta with a muzzle. Now, it is quite apparent that he was taken in the Eastern Park. And if he had been walking his dog, there would have been no muzzle. The KGB probably did not figure out what this Osta was. And I was told that he wrote it that way as a clear sign that no, my dears, it is not pleasant here, of course.

I heard from Protodeacon Joseph Yaroschuk that there were persons who went to Russia from Morocco on NTS assignments but never returned. But I recall that you and I were in Berlin in 1990 right after the wall was taken down. And the West Germans were joking that “If we only could, we would have built that wall ourselves.” This was because almost immediately many new problems appeared. And this is how I see the Russian diaspora: it was easy to love a Russia which people molded in the way they understood it. And when this Russia is here before you… I remember our catechism teacher at Jordanville, a wonderful priest named George Skrynnikov, whose Russian was such that you couldn’t tell where he came from. But he was from Serbia. And he would say, “These aren’t Russians, these aren’t Russians.” This was specifically about our 1990 class. And he loved us and treated us wonderfully. But this was the kind of encounter. This is already another topic, of course. And simply to conclude this, I will say that I have seen how the NTS somehow found itself in the thick of all this and did not separate itself from Russia. It never took account of the people who lived there. It was as if it wished to serve Russia.

But how was it possible to serve? Ideally, it would be through the word. I did translations into German myself, and I read and printed those same photo strips. That’s putting it mildly, for those were copies. Erika takes four copies. (The typewriter – ed.). Someone photographs in Russia and the film (of a manuscript – ed.) is brought out. Later on, I was directly involved with bringing out these films and their hiding places. Then the film is printed on paper, and the typist retypes it. And so, in Vasily Grossman’s book Everything Flows [Vseo techet] there is a misprint about consumer [potrebitelʹnye] organs. But the typist, who saw a square and a circle, read that as iz [iztrebitelʹnye, which made it into “destructive”, “exterminating”] rather than po, because everything was pale and fuzzy there. For example, there is also a work like Babi Yar by Anatoly Kuznetsov. All spots excised by the censors are in italics. This was followed, I think, by The Master and Margarita. We put it out – and I say conditionally that we, the NTS, Posev, put out only spots where excerpts have been cut out. And so my mother is sitting there and collating the novel, thinking, where can I put this? Some of the items are very interesting. For instance, the censors wrote that one of its heroes, a porter, is saying something trusia [while shaking]. But she changed it into trus ia [I am a coward], since cowardice is a theme in The Master and Margarita. But the censors had changed it to trusia. This was a moderation of the theme and was done very subtly. The literary critic Leonid Rzhevsky also wrote a book about this, how this would occur. The barriers of censorship and bans on thought had to be removed, and freedom of thought was brought back through that same Solidarist Library which Roman Nikolaevich Redlich was making. Whom to choose from there? I already mentioned Ilyin and Frank. And then there’s Berdyaev. All this was being sent to Russia as small books. We shipped them out. Zoya Krakhmalnikova was a contact with the blessing of Vladyka Anthony Bartashevich of Geneva and Western Europe. I do know who would visit Zoya, both Felix and Zoya. My mother was in direct contact there. Or there was George Vladimov. In 1972, I believe, they created the All-Union Organization of Authors’ Rights (VOAP in Russian – ed.) All authors were being driven into some Soviet organization to ruin Solzhenitsyn. But later, when Solzhenitsyn came to Zurich, we naturally met him there, since my mother had worked on the Posev six-volume set. He later praised her abilities, and she didn’t go to Vermont just to visit but worked like a family member under his guidance. We still have their corrections to Cancer Ward.

I have not sent you her corrections to Pravoslavnaia Rusʹ that she had sent me. I will send you her proof symbols. She would take an issue of Pravoslavnaia Rusʹ and make corrections. It was great.

Roman Nikolaevich Redlich’s wife, Ludmila Glebovna, is from Serbia. Let someone tell their story. But her father went off to Russia. She found out, sometime around 2000, how he perished there. He was Gleb, and they had a last name like Skuratov. She was Skuratova. And she would laugh, saying: “When my mother dies [that is Fr. Nikolai’s -ed.], there will be a mail slot on her gravestone, and another slot on the other side.” So you would stuff a manuscript into a slot, and the edited manuscript would come from underground through the gravestone and out the other slot. Both philosophically and spiritually there was a need to help people lead their lives.

Conducted by Protodeacon Andrei Psarev

Endnotes

[1] A popular satirical Soviet magazine [trans.].

[2] This is incorrect. Vladimir, the older son, was a distinguished theologian, it is true, and did live in Paris, but died prematurely in 1959. And Andrew lived in Los Angeles from 1950 till his death in 1998 and was a French history professor, not a theologian [trans.].

Links

A Message to the Participants in the Conference “A Scientific Orthodox View of False Historiography”

Archpriest Nikolai Artemoff, “The Russian Orthodox Diaspora: Copenhagen 1987-1988”

References

| ↵1 | I have mentioned his father, Prot. Alexander Elchaninov, here. Kirill headed the L’aide aux croyants organisation that helped believers in Russia. –P.А. |

|---|