From the Interviewer

In the last century, the Orthodox Church, and particularly the Russian Church, found itself exiled to nearly every corner of the globe. The Russian diaspora eventually coalesced in its highest concentration in the United States. Many figures in the Russian diaspora, most notably St. John of Shanghai, considered this to be part of God’s plan for the Orthodox Church to fulfill the Great Commission to baptize all nations. Thus, while not all bishops of the ROCOR necessarily considered missionary work to the “natives” around them to be a primary focus, they always took interest in anyone who approached them to learn about Orthodoxy, and were interested in helping them begin new missions.

Since this time, there has been an influx of converts from western Christian or post-Christian backgrounds into the Orthodox Church, which presents many fascinating anthropological questions about the interplay of culture and faith. This phenomenon is perhaps best represented in the person of Archpriest Gregory Williams, who, after joining the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in 1980, was quickly elevated to the priesthood, and spent his life publishing Orthodox literature in English. The most notable of these publications was the near-complete series of Liturgical service books, which was accomplished in collaboration with the prolific translator Monk Joseph (Lambertsen).

A rather unsatisfactory article about Father Gregory’s maushka, Anastasia Williams, was published in 2019, which failed to give an accurate account of the family’s work and of the “Agape Community” they attempted to create in the mid-1970s. To answer these anthropological questions and to correct the record about the Agape Community, I decided to interview Father Gregory’s son, Archpriest Matthew Williams, in fulfillment of the course requirement for the graduate class The Russian Church Abroad: Its History and Identity at Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville, NY.

On April 9, 2024, I interviewed Father Matthew during the Eastern American Diocese Northern Clergy Conference at Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY. Rather than focus on the numerous polemical works associated with his Father Gregory’s later work regarding the reunification of the ROCOR with the Moscow Patriarchate (he left the ROCOR following the reconciliation), we chose to focus on the story of his coming to the Church, the Agape Community, his publication work, and the significance of his work to English-speaking communities of the Orthodox Church today.

Timothy Zelinski

First, tell us the story of your father’s conversion to Orthodoxy.

My father, Archpriest Gregory Williams was born in 1941. He was a graduate of Nashotah House, an Episcopal Seminary in Wisconsin. After his graduation, he was not recommended by the seminary for ordination in the Episcopal Church. But through his studies of the church fathers, he had at least began to have an understanding of the origin of the church.

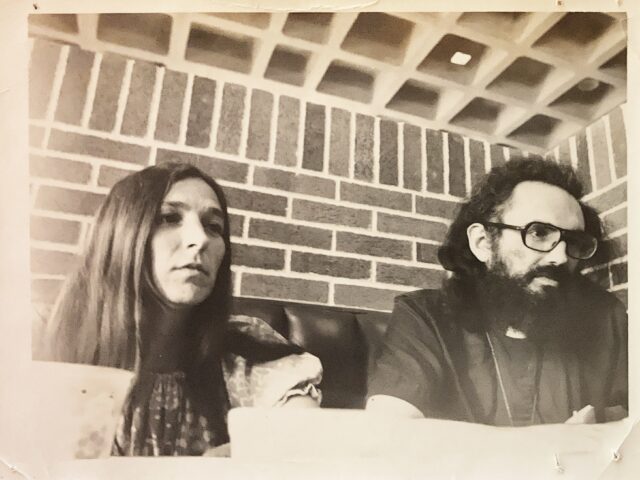

Fr. Gregory and Matushka Anastasiia in the 1970s

Around the same time, he became acquainted with a bishop who was descended from the episcopal lineage of Efthimios Ofiesh – an Arab bishop who, at one point, had been part of the Russian Diocese in North America, which was, at that time, known as the Metropolia.

He became acquainted with this bishop and was ordained by him. From that time on began to call himself Orthodox. His actual conversion and baptism into the Orthodox Church came much later. This would’ve been around 1970.

I believe that bishop was “Metropolitan Christopher.” I do not have a last name or any other details except that he was connected with Metropolitan Trevor Wyatt Moore in Philadelphia, who visited Liberty and with whom my father was associated up until 1980. He was working on a PhD in Chicago between seminary and meeting my mother in 1971.

How did he then find his way to the canonical Church?

That path includes the beginnings of Agape Community, and includes marriage to my mother, which happened after his non-canonical ordination – as is seems to be common in these groups…

Between seminary and meeting my mother in 1971, my father was working on a PhD in Chicago. In the early ’70s, around 1973, my parents bought property in Liberty, Tennessee, and lived there from that time forward. Only in the last few months, my mother has moved from that property. The story of their conversion and joining the Orthodox Church is tied with their life there, as well as their desire to live a liturgical life, and their acquaintance with Father Seraphim (Rose), and their trips in the late ’70s to St. Tikhon’s Monastery and Holy Trinity Monastery.

By the beginning of 1980, they were of the mind that they needed to join the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. Both of my parents were baptized by Father Vladimir Shishkov. My little newborn brother was also baptized by him. My father was then ordained in New York City in the summer of 1980 in the Synodal Cathedral by Bishop Gregory (Grabbe).

Could you go into a little detail about those encounters they had with Father Seraphim (Rose) and the different pilgrimages they were making?

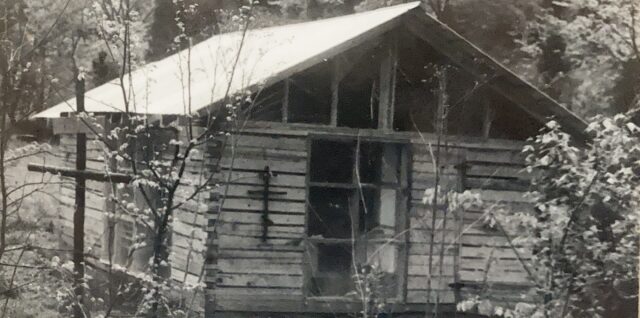

The chapel in the Agape community. The late 1970s

I have vague memories myself. I was born in 1976, so I was very young. But I have vague memories of at least one trip to Platina. My first memory of the trip to Holy Trinity Monastery was at the time of the glorification of the New Martyrs in 1981, so my knowledge of that journey into the ROCOR is more from conversations with my parents than my own experience. The one thing that my parents always felt about Holy Trinity Monastery is that when they came here the first time, they felt like they’d come home. This would’ve been in 1979. This was, I think, a pivotal moment in their decision to join the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia rather than pursue joining one of the other canonical jurisdictions in this country.

It’s interesting that coming to Jordanville in particular would’ve been their “coming home” moment, as it were. As an American family coming into what, at the time, was still a very Russian environment in Jordanville. Do you know who was their primary contact in Jordanville? There were a couple of monks who dealt with the converts in particular. Do you remember who it was?

I know who we were in contact with a bit later. I am almost certain that the future Metropolitan Hilarion was one of those people. And the reason I think that is, my earliest memory of Metropolitan Hilarion is his absence from the monastery. I visited here in November of 1984, and I have a memory of standing in the upper choir loft, where visitors are no longer allowed. I asked one of the monks that was standing there where Father Hilarion was, and he answered that Father Hilarion had gone to Manhattan to be the bishop.

At that age, you would think that I would know where Manhattan was, but I didn’t. I asked what’s Manhattan? And he said, “Well, it’s an island.” And I had this definite vision of Father Hilarion going to be a missionary on an island (laughs).

At that age, you would think that I would know where Manhattan was, but I didn’t. I asked what’s Manhattan? And he said, “Well, it’s an island.” And I had this definite vision of Father Hilarion going to be a missionary on an island (laughs).

That’s all he said, an island? Nothing else?

Well, maybe he said more, but it didn’t register. This was the vision I had. I think I was corrected very soon and understood the reality. I didn’t associate Manhattan with New York City at the time.

You would’ve been around eight years old, I guess, at that time.

Yes, around my eighth birthday. My parents were also acquainted with Archimandrite Vladimir, of course. I also have memories of the old bookstore—many memories of the old bookstore. And Father Kiprian, although he didn’t speak English, communicated with my father at various times. He was maybe the Deputy Abbot at the time.

There was also Hierodeacon Ephraim, who, unfortunately, is no longer here. He was a close acquaintance of my family, and there are probably many others that I know even know, but don’t have specific memories of from those early years. Of course, much later in the mid and late ’80s and ’90s, our family would visit here about once a year. And so, there are lots of memories. Some of them might be out of order.

Now, about your father’s journey to the Church in the first place, you mentioned that he got some ideas about the original Church or the foundational Church. Was there any particular book, publisher, a particular Church figure that he was interested in that you’re aware of?

I’m not aware of any specific writings, or authors, or historical figures that were instrumental in his movement towards Orthodoxy.

I ask because your uncle and Father Gregory’s younger brother, Father Chad, largely came into the Church because of the books he read. I believe it was the compilation of the Philokalia “On Prayer of the Heart” and The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which had recently been translated into English, that impacted him. He read those books, not being Orthodox, and basically came into the Church because of them.

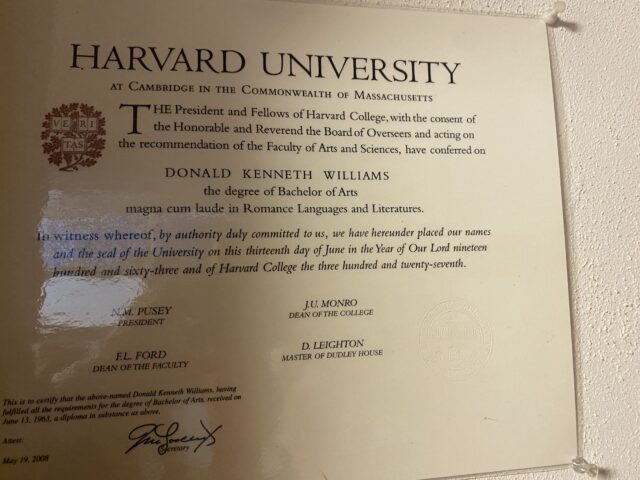

My mother might know. As an aside, I have to sort through boxes and boxes of things in the print shop. And I know there are some of his college writings from Harvard that are in there, and various papers, and so forth. So I might find something. He wrote a lot at that point in his life.

Fr. Gregory’s B.A. diploma in Romance languages from Harvard University. The early 1960s

By the way, he wrote a book called The Sacramental Life that might also help glean insight into the history of him becoming part of the church. It’ll give some insight into his way of thinking about the Church. That may even be here in the bookstore, I don’t know. I’ll have to see. Maybe in the library.

So they decided to come into ROCOR, and he’s baptized, and ordained pretty much back to back, as I understand it.

Yes, within a few weeks.

And that all coincided with them beginning the Agape Community, or at least when they were attempting to begin it?

No, not at all. Agape Community at that point was in its decline. The Agape Community was established, I believe, in 1973, at the same time that they bought the property. They bought the property with this idea in mind.

And you were born there?

Yes. In 1973, they bought the property and moved to Liberty, Tennessee. My older sister was born in 1974. By the time I was born, there were several families living on the property. At any given time between when I was born – or when my sister was born – and the mid-80s, there would be anywhere from zero to three families living at Agape Community. None of those families ever joined Agape Community and became full members as envisioned by my parents. The reasons for that are probably self-apparent to anyone who reads the bylaws and understands what the vision was.

What would those problems have been?

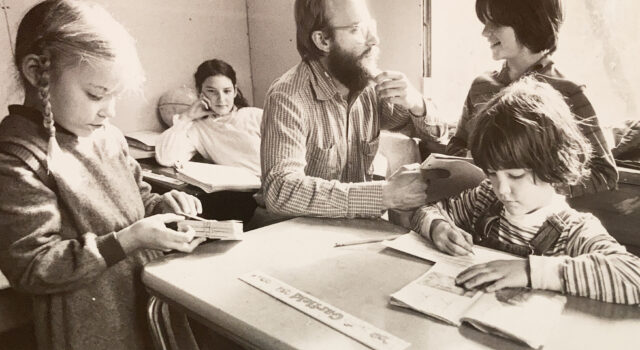

Homeschool at Agape in 1986. L to R: Catherine Stade, Mary Sara Williams, Christopher Stade, Matthew Williams, John Williams

Agape Community was envisioned as an Orthodox settlement, although I think the vision of Orthodoxy was originally pretty far off. But the vision wasn’t set aside when they actually did join the Church, which was to have a settlement of Orthodox Christian believers that held everything in common. I think this is the key problem. It’s hard enough for monastic communities to hold everything in common. It’s much harder for families with children, and spouses, and so forth. So the level of commitment for anyone other than the founding members was too difficult. It was difficult even to this day for my mother, since she had put everything she had into this. It was difficult for her that she put everything she had from her inheritance and into this organization. But at least she and my father had effective control, if not ownership, of all these resources. Anyone else that came subsequently would have a much more difficult time with that. Going to that level of commitment – which is really a lifelong commitment if you have much in the way of resources. I think this is probably the number one reason. It’s an unrealistic utopia.

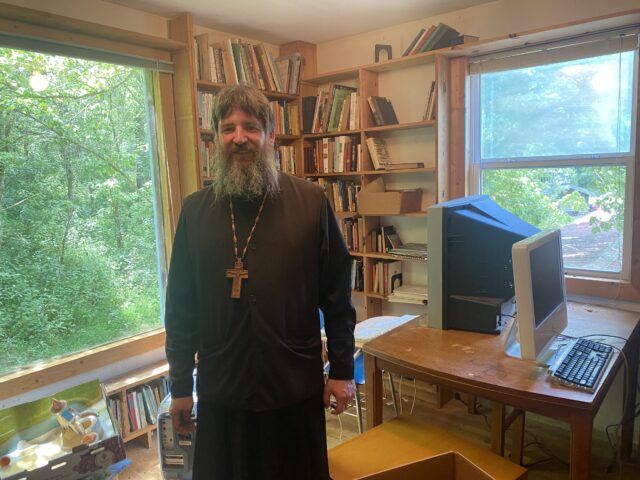

Archpriest Mathew in his former classroom. August 2024

Undoubtedly, there are other reasons, including personalities, and so forth. It’s a very difficult life. There was no electricity at Agape Community until 1983 or 1984, and it remained so until the mid-80s. No electricity means no air conditioning, and Middle Tennessee can hit a hundred degrees in the summer. There were not even any fans! It was a very primitive way of living.

Most monasteries aren’t that intense.

No, they aren’t. I think Platina was, or close to that, at least at that time. I don’t know that it still is.

Today, it’s not. It’s still very austere, but…

They do have electricity (laughs).

Yeah. I believe the Serbian Bishop Maxim of Western America ordered them to start introducing some of those modern “comforts” in Platina for the sake of the archives there and also for the sake of health.

Inside of the church. August 2024

To this day in Liberty, there is no electric lighting in the chapel. I think today we heard from Bishop Luke [ed.- during the Clergy conference] that he doesn’t really like electric lighting and certainly not advanced technology in the way of electric lighting. It’s actually something that I’ve been contemplating at our own parish where I serve now – not to have electric lighting. Bishop Luke just gave me a nice push in that regard.

I bet he liked to hear that. He has a very good point that the prayerful experience within the church changes because of the electric lighting. The icons don’t look right, essentially. The whole theology of icons is based around light. Each layer is called a light. Everything functions off of how natural light and candlelight, or lamplight, reflects off of it.

At least incandescent is a natural glow generated through a wire as opposed to these technologies with glowing gases or minerals.

So it seems that the Agape Community idea seemed to go to the back burner, as it were, as they come into canonical Orthodoxy. And the focus then shifts towards publishing, if I understand that correctly.

St. John of Kronstadt Press is under construction. 1985

Yes. The beginnings of the publishing more or less coincided with joining the church. The periodical, Living Orthodoxy began being published in ’78 or ’79, and continued to be published up until the time of my father’s death in 2016. Also, around 1980, I think it was probably soon after his ordination by Bishop Gregory, there were several small booklets that began to be published.

In the first half of the ’80s, St. John of Kronstadt Press, which was the name that the publishing company took on, had published and/or printed several books including [The Lives of] the Three Hierarchs – which was printed on behalf of Holy Apostles Convent in Colorado – and the Lives of the Apostles, and quite a few small paperback books, along with many lives of Saints, the Services, Akathists, et cetera. It was also during this time that my father formed a close relationship with Brother Isaac Lambertsen, or Monk Joseph, as he was tonsured shortly before his death.

Were they doing all of the book printing themselves physically, with old equipment, in addition to this? Or was it more of a traditional… well, not traditional – but I should say, more of a standard publishing business?

With outsourcing?

Yeah, with outsourcing.

I would comment that in the early ’80s, that wasn’t the norm. Small print shops were much more common at that time. Platina had their own print shop. St. John of Kronstadt Press had its own print shop. And Holy Trinity Monastery itself had a very large print shop where all the printing was done in-house. So St. John of Kronstadt Press was not any different. We had several small printing presses starting even in the late ’70s. Before there was electricity, we had a diesel generator to run the equipment. And then in 1985, a large printing press was purchased.

St. John of Kronstadt Press was contracted by the Church of the Nativity in Erie, Pennsylvania, to print the Old Rite Prayer Book. So, the first edition of the Old Rite Prayer Book was printed, although not published, by them. At this point, it was actually several books that I’ve already mentioned, and the Old Rite Prayer Book was printed for other publishers. So it was actually the reverse. It’s St. John of Kronstadt Press that was one of the outsourcing for parishes or publishers that did not have their printing equipment.

By the mid-80s, or at least the latter half of the ’80s, St. John of Kronstadt Press began publishing the services from the Menaion that Monk Joseph [Isaak Lambertsen] had been translating at least since the late ’70s. Originally, those translations were in typewritten form. With the help of a typesetter, they were made available. By 1985, St. John of Kronstadt Press had desktop publishing equipment. It was the first desktop publisher in Middle Tennessee.

So, in 1985, we purchased an Apple LaserWriter. We also bought a Macintosh computer and a scanner. The quality of printing dropped considerably in the mid-80s versus the early ‘80s. If you look at books published in the late ’80s by the St. John of Kronstadt Press, the high-quality halftones were created through the photographic process and went to the offset press. Many were attempts at scanning through a 300 DPI scanner and printing on a 300 DPI printer. That was not very satisfactory, but such is technology. You have to go off a cliff before you can start to climb out of it.

But, at the same time, it allowed us to print in low volumes effectively. The desktop publishing software allowed us to prepare materials for publication much faster and more efficiently, as opposed to the older photographic image setters that were necessary before then. So, it was really in parallel with the acquisition of this desktop publishing software and hardware that we began to make the Sunday services from the Menaion available on a monthly subscription.

Father Joseph would translate something, or he’d send something he’d already translated, and it would be typeset, and be prepared for printing. A month’s worth or so would be printed and mailed off to English-speaking parishes across the country. This went on for about five or six years, by which time we had the entire Menaion in this loose-leaf format that was being sent out to be put into ring binders. So it was in the early ’90s that the Menaion was ready to be published in hardbound editions.

It seems providential that Father Joseph was finishing all of these translations right when a print shop showed up interested in them and was able to do the work to publish them.

I would not describe him as having finished the work. It was more like he was getting into full swing, because he continued to translate pretty much until the time of his death. He was still, in fact, working on some translations of some of the Services to the New Martyrs that were being composed simultaneously in Slavonic.

I see. When did he repose?

Father Joseph reposed in January 2017, just a few months after my father. He continued to work in translation throughout his 30-year period. Of course, in addition to the Menaion, he translated the Octoechos, many lives of the Saints, and the Pentecostarion. He also translated, although it’s not been published, the entire Trebnik [Book of Needs]. So, there are considerable unpublished materials that he translated that are still in need of publication.

Did they – your parents, I mean – procure other translations for different things? Or was Joseph their main source of liturgical material that they were putting out?

When it came to liturgical materials, absolutely, although there was occasionally something that someone else translated. The periodical, Living Orthodoxy, had a broader range of contributors. And there were the occasional book that was published, or co-published, by the St. John of Kronstadt Press that was authored and/or translated by somebody else.

L to R: Dimitri Wieber, Oleg (from Hartford, Connecticut, an old emigre family), George Chemodakov, Mary Sara Williams, Xenia Woerl, Rachel Williams, two more Woerl children with Bishop Hilarion behind them, Matthew Williams, Nicholas Woerl, Marie Reeves, Fr. Gregory Williams, John Williams, Anastasia Williams, Michael Woerl. Agape Community. 1991

A couple notable publications of the St. John of Kronstadt Press were the English translation of the Spiritual Psalter of St. Ephraim. Father Joseph translated the life of St. Ephraim that’s included in that, but the text itself was translated by another translator. The One Thing Needful by Archbishop Andrei of Rockland, which was co-published by the St. John of Kronstadt Press and the Diveevo Convent and translated by either Father Gleb Vleskov or Father Alexander Feodorosky. And there are several other books, including the Commentary on Psalm 118 by St. Theophan the Recluse, and On the Prayer of Jesus by St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov). None of these were translated by Father Joseph. So, while he translated the vast majority of the liturgical books, some of the other publications were submitted from elsewhere.

Did you mention the Commentaries of St. Theophylact as well?

The Commentaries by Blessed Theophylact were published by Chrysostom Press, which was Father Christopher Stade’s, who ran Chrysostom Press and translated Blessed Theophylact. There was a connection between the Stades… I don’t know if you want to go into that anyway.

We’ll save that one for next time. A couple of months ago now, I interviewed your uncle, Archpriest Chad Williams, who is the youngest brother of how many?

My father was the oldest, and Father Chad is the youngest. In between them, there was a sister and two brothers. So there were a total of five of them.

The two of them came into the Church more or less independently through different means, yet both became Archpriests in ROCOR. One of the questions that John Kurr and I were trying to answer with Father Chad is about the interplay of culture as an American convert coming into a heavily Russian environment. This was especially the case for Father Chad because St. Alexander Nevsky parish in Richmond, ME, to which he was assigned, was all Russian. How did your father view that cultural interchange? Did he feel a kind of closeness to that Russian village life and how he was living before coming to the church?

Fr. Gregory, Matushka Anastasia with children and family, and Fr. Chad (on the right) in the early 1990s in Liberty, TN. As of August 2024, Fr. Matthews’s blood and extended family consists of eight priests serving in ROCOR’s Eastern and Mid-America Dioceses and Antiochian Archdiocese

No, and that’s an interesting question because I’ve actually pondered this myself. It seems like there was a contradiction at times in the relationship that my father had with Russian culture. He was staunchly opposed to the use of Slavonic in the services in English-speaking communities. And I think this certainly was a driving factor in his desire to publish the services in English.

At the same time, he also had a great respect for Russian culture, and Russian Orthodoxy, and he was close with many Russian speakers. I think that his opposition to using Slavonic in the services was tied to what he saw as a disconnect between an English speaker choosing to use Slavonic, with their own roots. That, perhaps, in choosing to use Slavonic for someone for whom its a second language at best, is itself so ungrounding. But he certainly had tremendous respect for the monks here at Holy Trinity Monastery. And of course, all the services here at the time were in Slavonic.

He also would often tell the stories about how he would come and ask a blessing to serve. On one occasion, he asked a blessing to serve in English liturgy in the cemetery. And he was blessed to serve at the Cathedral in English, and they assigned a deacon to serve with him in English.

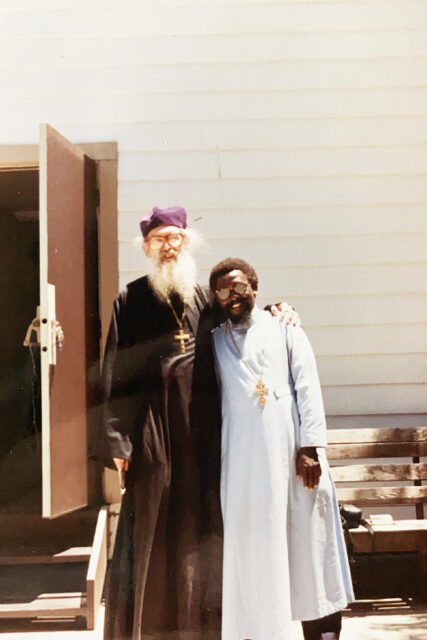

Fr. Gregory and Fr. Christopher Walusimbi, a ROCOR missionary archpriest from Uganda, at St. John’s glorification in San Francisco in 1994

So, although we usually hear about how, in the ’80s, the use of English in the Cathedral would turn lots of heads – which is true – there were certainly times when English was used. I think he would look at the ability of the monastery – and of then Archbishop Laurus and of the other fathers here – to not be rigid in this matter as a very positive thing in support of the English-speaking clergy and the English-speaking communities.

While the monastery at the time felt that its services should be in Slavonic, it was not opposed to the use of English, at least collectively, in parishes. And so, there was a pastoral benefit to allowing visiting clergy to serve in English occasionally here.

I guess in this case, taking on the faith was essentially just that. It wasn’t necessarily taking on culture. It was more of an enculturation of what they already had, but within the fold of the Church. Would you say that’s accurate?

I think that it was a combination. Certainly, my father was not a Russophile, but he was also not a Russophobe. I think that that resulted in his personal life and in his life as a priest in a very small parish of the Russian Orthodox Church to have a grounding within Russian Orthodoxy without [taking on Russian culture]. But at the same time, I would not say that he fully embraced Russian culture.

The reason I wanted to point that out is because one of the narratives going around now is how rural Americans are coming to Russian Orthodoxy – and consciously choosing “Russian” Orthodoxy – out of some political or cultural affinity. But if we look at an early convert community – or, relatively speaking, earlier convert community – it doesn’t necessarily seem to be the case. If anything, it would be only because they found themselves in a heavily Russian environment. Converts like, perhaps, Father Joseph himself, who lived in Synod then, naturally had to become a fluent Russian speaker just to get by. Or Father Chad – In his case, his church was all Russians. He was an American priest in an all-Russian church. So necessarily, he had to adapt himself to the culture in a way that his older brother clearly didn’t need to.

He did not need to, and probably would’ve avoided being put in that situation. But yes, he did not have a necessity to learn Russian, and he did not learn Russian. I don’t think he ever even had any intention or attempted to.

But you, on the other hand, did.

I did. I had an interest in Russian from visiting Jordanville. So I first started studying Russian here in Jordanville. I was given my first Azbuka in, I believe, it was in 1987.

Can you explain what an Azbuka is?

It’s the Russian ABCs. I was given that and learned to read the Trisagion Prayers. I was given one of the Jordanville old orthography prayer books. I was given all these, I believe, either in 1986 or 1987 for my birthday when I was here, and began to study from that time casually. But I started to learn the alphabet, and could sound things out, and could read the Trisagion Prayers soon after that. Of course, I really only started to study Russian when I came to seminary in the mid-90s, though I began to study Russian in the late ’80s. Probably there would at least be at times that I might’ve been described as a Russophile (laughs).

I point that out also because your cousins, Fathers Nathan and Anthony Williams] are also priests, and have done the same thing.

They’re much better than I am. Definitely much better than I am.

But you do speak fluently though, so I think we can give you some credit for that. You also serve in Slavonic and you do your litanies from memory in Slavonic, so I think you’ve earned your points (laughs).

Reasonably fluently, I can speak Russian.

Your family, partially because of that, has very much become a part of the fabric of ROCOR now over a couple of generations.

It seems that way. There are seven priests living that are either directly descended from my grandparents or married to their granddaughters. With God’s help, we’ll soon have a few form the next generation joining the seminary.

God willing! In our pre-interview chat, we discussed your grandparents, and whatever influence they might have had to produce such fruitful offspring within the Orthodox Church, which I’m sure they could probably never have imagined.

They probably could have never imagined it, yet my grandmother converted before her death.

She did?

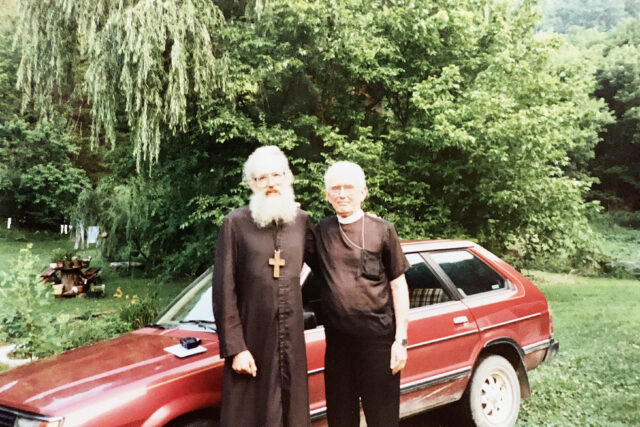

Fr Gregory with his father — Rev. Kenneth Williams, an episcopalian priest — in the late 80s

Yes. My grandfather was an Episcopal priest finishing his year serving as such in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Maybe he wasn’t retired at that time, but he left that parish in the early ’80s, but he might’ve served elsewhere later. But he served for many years, decades, as an Episcopal priest. So my father grew up as the son of an Episcopal priest.

My grandmother was a musician. Clearly in their own way, they were very faithful, albeit outside Orthodoxy. My grandmother ultimately wound up living with Father Chad, my uncle, towards the end of her life, and chose to embrace the Orthodox faith in her last years. Father Chad and I served her funeral.

If you walk into the kliros of one of these parishes, of which there are hundreds in this country and many more in other English-speaking countries, it’s unlikely that you won’t encounter the Menaion published by the St. John of Kronstadt Press.

I’ll combine the last two questions here. What would you say was the impact of your father’s work? And how does that speak to the experience of converts today – yourself being a pastor to many, many new converts?

At this point in the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad – not to mention other English-speaking communities, especially those of Russian traditions, such as the OCA – if you walk into the kliros of one of these parishes, of which there are hundreds in this country and many more in other English-speaking countries, it’s unlikely that you won’t encounter the Menaion published by the St. John of Kronstadt Press, and the Pentecostarion, and the Octoechos, et cetera.

At this point, some of these books are available in some form from other publishers. Especially within ROCOR, most of these parishes are using the books published by St. John of Kronstadt Press, which I think speaks to the impact. If we stand in a Vigil service, the Canon that is read is going to be Father Joseph’s translation published by St. John of Kronstadt Press. The rich liturgical life of the Russian Church has been made possible in English.

In its fullness, too.

In its fullness. The full richness of the Orthodox tradition is accessible now through the work of my father and Father Joseph.

Fr. Matthew and Matushka Anastasia. Agape community. August 15, 2024

Before the mid-80s, or even well into the early ’90s, if you were doing weekday services, the General Menaion – a book that I think a lot of people don’t even know exists at this point – was your standby. You had to have that on kliros because that’s where you went if you didn’t have something else.

That’s all you had.

Yeah. I remember singing the same service to the Martyrs over and over again, because we had daily Vespers at our chapel. And so, sometimes you’d have three or four days in a row where you’re singing the same Stichera to the Martyrs with a different name inserted. Father Joseph translated the General Menaion, but it never got published.

There’s no need.

No, there is an occasional need, and it’s something that it would be good to see published. The publication that we had access to back in those times, I don’t think is in print anymore. I don’t know where you would even go to buy a General Menaion. It’s not a question people ask me or that I hear people asking, but I think that all the same, it is worth having it. And so, maybe someday it’ll be published so that parishes can use it as a supplement if they have a lower-ranking service for their parish feast day.

They spent their entire lives with Jordanville services, which were almost exclusively Slavonic. But through their life’s work, now Jordanville – where they started – is serving in English.

I’ll also mention that now, at the monastery, the majority of novices are English-speakers only. So, those books are open on the monastery kliros almost more than the Slavonic books for the daily services. It really enabled the monastery to get new blood. They’re able to do services very faithfully in the way that they’ve always been done at Jordanville, but in their own language now.

Agape community church, Liberty, TN. August 2024

Yeah, so this comes full circle. My parents showed up here in 1979. So did Father Joseph, I think, or maybe a little bit earlier, also as a convert. They spent their entire lives with Jordanville services, which were almost exclusively Slavonic. But through their life’s work, now Jordanville – where they started – is serving in English.

They’re able to give back to Jordanville, where they had received so much.

And this is a beautiful thing that we see in Jordanville. Over and over again, we have people that came here as converts or young Russian men, coming to seminary, and now they are the senior monks, clergy, professors, and that includes is the dean himself, of course.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Maybe later (laughs).

Great. I think that’s a good point to end on.

Conducted by Timothy Zelinski