From Editor

Just recently, we posted an interview with Fr. Ioannikios (Abernethy), in which he talked about Holy Trinity Monastery in the 1960s and the 1970s. The publication of Fr. Ioannikios’ interview served as a reminder about another interview I recorded in 2011 with Dr. Dana Miller. In it, Dr. Miller, a Classics scholar with particular expertise in Greek and Syriac philosophy, shares his recollections of the same timeframe, although from a somewhat different point of view. He covers the Western rite, his life at Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanvile and Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Brookline, MA.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev,

Jordanville, NY, August 23, 2024

So, I understand that you are from France.

Dana Miller: No, I’m from here.

Really?

Yes, but I was studying in France at the time.

What was the time?

It was 1965, 1966. I went, basically, to learn languages. I was in college here. I spent a couple of months in Germany in ’65 at the Goethe Institute, so I must have arrived in Paris around January of ’66. I had no Christian religious background at all. My parents were sort of nominally something-or-other, but I never went to church when I was a kid. There was no exposure whatsoever. So then I was staying with a friend of my girlfriend at the time, who was in the States. He was a Frenchman and, for reasons I never understood, he would go from time to time to the Kovalevsky church.

But he was not an Orthodox himself.

No. He was just sort of a French nobleman kind of guy. He was just interested. I don’t know where the connection came. I never understood why he would be going there and how he knew about it. He lived in a whole different part of Paris. So I went along with him a couple of times, and I didn’t really have any positive or negative ideas. I just went for…

For the experience.

Yes. For the experience. (I have to back up a little bit.) When I was in college…

You didn’t mention what college.

It was St. John’s College.

Oh Really? So you are a “Johnnie.”

Yes.

That explains some additional things about you.

Yes. You know Ossorgin, right?

Yes. Annapolis, I assume?

Yes, Annapolis. But Ossorgin had just left when I got there. He had just gone to Santa Fe. They were just opening up Santa Fe when I was there, so I never met Ossorgin. So he wasn’t an influence at all. But I was studying Greek philosophy, and I said to myself: “Where did all the Greek philosophers go?” You get to the fifth century A.D., and there are no more. What happened? So then I was looking around and I ran into Patristic writings.

So this was before your trip to Europe?

Right. So I had already familiarized myself with some Patristic writings. It had given me the sense of a Platonist kind of influence, but also some Chrysostom and some other people. But I thought it was really interesting stuff. My only impression of Christianity was Protestants talking about Easter eggs, which seemed completely inane and stupid to me. But I said, “Wow, these people were philosophically very astute, very educated, very smart, very interesting.” But I said, “That kind of Christianity doesn’t exist anymore.” So, that was a big revelation to me, that Christianity actually was interesting at one point.

So you discovered [the Fathers] on your own.

Right. Then when I went to the Kovalevsky church I got into a long discussion… First of all, the Kovalevsky church was of some interest to me because everything was in French. And I could actually understand some of what was going on, which was helpful. After church, this guy that I was living with introduced me to the Kovalevskys.

[Kovalevsky] was not a bishop yet, I assume.

He was. This was right after Vladyka John had been transferred to San Francisco. Or maybe he was still there, but…

He had just been consecrated.

That’s right. Then [Kovalevsky’s] brother, Pierre, and I got into this long conversation. I didn’t understand who these people were, what is Orthodoxy about? I had never heard of it before. So I got into this long conversation with Kovalevsky’s brother Pierre and I said, “Well, you know, Christianity a long time ago was actually kind of interesting. I don’t know what happened to it, but it was interesting once.” He said, “What do you mean by that?” I started citing some of the people I’d read. He said, “Oh, we’re still interested in those people. Those are the people we most admire.” I said, “Oh, I didn’t know anybody even knew those people existed anymore.” So then we got into this kind of interesting discussion, and I saw that Orthodoxy actually had a kind of respect for and had continued some of the thinking spirit that I saw in some of these early writers. And so that got me really interested. I said, “Wow, this is different.” So then I started going there with this friend of mine, the fellow that I was living with. I eventually left and got an apartment of my own, but I came to the church fairly frequently, on my own. I was going to the Alliance française, and right down the street was the home of Editions Budé. They have French and Greek Patristic texts, and also a lot of Greek philosophical texts like Plato and Aristotle.

So it’s a library.

It’s kind of a library, but they publish books.

I see.

They’re the main publisher in France for this kind of material. [In their editions] they have a translation and they have the [original] text. They have a lot of Patristic literature too. It was right down the street, so I would go in there and stand around an read a lot of Patristic works, as well as some of the old Classical philosophy.

So I got more interested in Patristics, and had further discussions with the people at the Church. So I said, this is a different kind of Christianity. I’m kind of interested. So I ended up getting baptized there. That was in August (or something) of ’66. About Jean Kovalevsky – the whole church was very strange. I mean, strange for me now when I look back on it. I didn’t really understand anything then, but they had a Black Madonna, a statue. They had a number of things for the Catholics, and then a number of what we would recognize as Orthodox icons. It was a mixture of Catholicism and Orthodoxy. I didn’t know anything about Catholicism or Orthodoxy, so it didn’t really seem out of place to me. It was a curious blend, and it was intentional.

What was the intention?

If you remember, they resurrected a liturgy. They had this liturgy of St. John someone, which was an early French…

Gallican.

Right. It was a Gallican thing that was not really Catholic, not really Orthodox. That was intentional. They were trying to make themselves acceptable to the French Catholics, but also trying to be Orthodox. The people that I met there weren’t emigres. There was an emigre church, and the Russians would all go there. They were mostly just French people of various kinds, the ones that I got to know. They were random French people that came in there and found it interesting. What else can I tell you about? Kovalesvky, Jean, was kind of stand-offish. He was removed. He was there, but he didn’t really pay much attention to you. He was friendly to me when I said I wanted to become Orthodox, but immediately after I came into Orthodoxy he had no time for me, didn’t want to see me.

Do you mean it was kind of like a cult?

I didn’t see that. If it was cultish, the idea would be that he would be the cult figure and would sort of pull people toward him. He wasn’t like that. He was the opposite. At least with respect to me, he wasn’t trying to set himself up as some kind of special spiritual guru.

Yes, that’s what I mean.

I didn’t see that. Not with me. With other people, I don’t know, but not with me. He was more, like, in his own little world, not really connecting all that well with people around him, that I could see. There was him and there was his brother. They were the centerpieces of the church.

Was his brother a priest?

No, he was a layman, as far as I know. He was a kind of academic. I think he wrote on art or something, taught somewhere. I remember reading a book of his, put out by a French publisher. It might have been on St. Serge of Radonezh.

They used to have their own institute, St. Dionysius Insitute.

Oh, that’s right. I remember going there.

So possibly it was an alternative to St. Serge (Institute). Maybe they didn’t use enough French at St. Serge, so they tried to create their own operation.

That’s right.

That’s just my feelings.

They were kind of an outreach organization. They were trying to make Orthodoxy more accessible to the French people. Paris at the time was an incredibly weird place. The French were very…

That’s right, it was around 1968.

For instance, there were a lot of French people that would be interested in astrology, they’d be interested in alchemy, they’d be interested in various kinds of Christianity, they’d be interested in Pythagoreanism, they’d be interested in acupuncture. There were lots of publications going around and people would go to all kinds of occult meetings. But they wouldn’t be interested in a serious way. It was like window shopping. They liked going around and exposing themselves to new stuff.

Something that wasn’t theirs.

That’s right. So there was a lot of that going around. I think that the Institute of St. Dionysius was trying to pick up on that, because there were a lot of these kinds of things going on in Paris at the time. I remember there was a Rudolf Steiner Center – he’s a weird guy who was popular in France at the time – and he had a whole [sort of] building and people would go in …

Theosophical stuff …

Yes. There were a lot of those sorts of things at that period in Paris. There was a lot of interest. I kind of got the sense that the intellectual side of the Kovalevsky church was trying to tap into that sort of thing.

They were trying to use a language that such people would already understand.

Yes. Spirituality, in some sort of broad sense. But it was pretty clear that they were Orthodox Christians. They weren’t something totally strange. There were plenty of strange people out there to begin with. It was helpful to me to be able to understand the Liturgy, because the Liturgy was in French. Otherwise, I don’t know whether I would have become Orthodox, simply because I’d had no contact with it all.

At this point the French church was part of the Synod, thanks to St. John.

For a short time.

That’s right. Then I came back at the end of the summer.

That was in 1966.

That’s right. So then when I came back to Washington I asked – it might have been Kovalevsky that I asked: When I go back to the ‘States, what church should I go to? And he said, “Well, we’re part of the Synod, so you could go to the Synod churches, but it doesn’t really matter. You could go to any of them.” He didn’t care. So I went to Washington. I was at St. John’s in Annapolis, Maryland, so to go to church I’d have to go into Washington. And then I went to the Metropolia church. There’s a hill in Washington, and the Washington Cathedral is at the top of it. Then there’s a Greek Cathedral and the Metropolia Cathedral – St. Nicholas or something. I can’t remember. I went to the Greek Cathedral and I didn’t like that. I couldn’t understand anything. Then I went to the Metropolia church and I didn’t like that. It was very cold and the people weren’t nice. There was something wrong with the whole atmosphere, so I didn’t like that. Then I went to the church over on Seventeenth Street, where Fr. Victor serves now. Even though it was nothing like it is now – the iconography was terrible and it was a small little building – but I liked the people and I liked the place. There was some kind of living spirit there.

They embraced you? Is that what you mean? They received you?

Well, they didn’t do that either. But there was something that you could tangibly feel, that there was some kind of living piety here. It wasn’t some kind of … like going into a museum, like the Metropolia place. And Fr. Nicholas Pecatoris was there. He was actually a Greek from Bessarabia or something. He was in Russia during the revolution. Eventually, in the ’30’s, it was possible for people of Greek descent to get out of the Soviet Union. He did, and then he went down to Greece and he joined up with the Old Calenderists. Then he came to the States, I think, after the war – a very interesting man. He was very receptive. He didn’t really speak any English, but he was a pretty wonderful guy. I liked him a lot. Then I finally got to know some of the other people. They became more friendly. There weren’t any other Americans there, only Russians. It was very much a smaller place than it is now. Now it’s large. So I was there for about a year, going to school, and I’d come over.

You were a graduate student, I assume.

No, no. Undergraduate. They didn’t have a graduate school then. It was just a college.

Now there is a Graduate Institute.

Right. They didn’t have that. Then I got more interested in what Orthodoxy really was. I didn’t really know what it was. I didn’t understand it very well. I liked it, but I didn’t understand it. At that time there was almost nothing in English, except for the Patristic material. Some of that was in English, and that was about it. So then I became more interested in that than I was in what I was learning at St. John’s. At this time there was a very close connection between Jordanville and the parishes. This was the ’60’s. There were several groups of Russian emigres. These were emigres that came after the second World War. Their living experience was a total hell that they’d been through, so there was a pretty intense connection with Jordanville as being a kind of anchor for their Russianness.

Very interesting.

They were clinging to their identity through Jordanville. They were holding on to being Russian by their connection to Jordanville. So Jordanville was a kind of center of their spirituality and their meaning as Russians. When I went up to Jordanville I was very impressed.

On your own?

I think I went by myself. There might have been some people that I drove up there with, but I can’t remember.

This was a couple of years after your return from France.

Yes. My first visit to Jordanville would have been probably in ’67. I think I went there for Velikiy Post [Great Lent], something like that. Then I decided to go to seminary.

You were already done with St. John’s?

No, I had one more year. But it was the ’60’s, and people did stupid things. So I just left and went to Jordanville, although I didn’t know a word of Russian and the classes were all in Russian. But I wanted to find out what Orthodoxy was all about, and I thought this was the only way I was going to find out.

A well-kept secret.

Yes, a secret indeed. So it took me about a year to understand anything that was going on.

But they brought you up to speed with your Russian?

Well, no not really.

They didn’t have any non-Russian speakers?

Well there was one other guy there, I think his name was John or Ioanniki.

I met him in Greece. In 1998.

It was a long time ago. He was there [Jordanville] before.

He became a priest and was named after St. John of Shanghai.

Oh? So he’s in some Greek monastery, right?

Right. He’s in an Old-Calendarist monastery of a moderate synod, the Cyprianite synod.

The Cyprianites.

It’s a suburb of Athens, or the greater Athens part – Attiki.

Right. I think I’ve been there many years ago, but not when he was there. So he was there [at Jordanville], but he was the only one. He was the only sort of non-Russian there. I guess I must be fairly good at languages, so I picked up the Russian very quickly. And then of course I had access to materials. I used to go to the library a lot and read everything I could get my hands on, to get the answers to my questions.

You mean already in Russian?

Yes

Wow.

I had taken some Greek, so then I got interested in Greek and started learning Greek again.

I’m sure there were classes in Greek.

No, there weren’t, not at Jordanville. [Addendum: Archbishop Alypy may have taught Greek –DM]

So you just started to explore on your own?

Yes.

At Jordanville?

Yes. I used to work in the bookstore with Fr. Vladimir. He would just give me the keys to the library and I would go back there.

You must remember Fr. Victor.

Which one?

Lokhmatov.

He was actually a year or two years ahead of me. He worked with Fr. Vladimir, and then I worked with them. I was there in Jordanville for almost three years.

So that’s what it took you to go through the program?

No, I never finished the program.

Really?

I went through the first two years and a half, and then I left.

Alright. You could probably claim your credits now and finish.

(Laughs) The reason I left was … Well Jordanville, I’m sure now, is better than it used to be. Academically it really wasn’t very good, to be honest with you. It was good for training people to become priests, but wasn’t really good for giving a broad education. But that wasn’t really my interest. It became clearer and clearer to me that the thing I really liked about Orthodoxy was the spirituality part. And then it was clear to me that in order to fully understand what that is, you need a much more sort of strict monastic kind of thing. I have great respect for the Russian monks at Jordanville. I liked a lot of people there and I thought they were great people. But to be there as a monk just didn’t seem to make sense to me. It was too distracting. There was too much going on. Another fact was that as a non-Russian you were kind of an alien. You were kind of a stranger there.

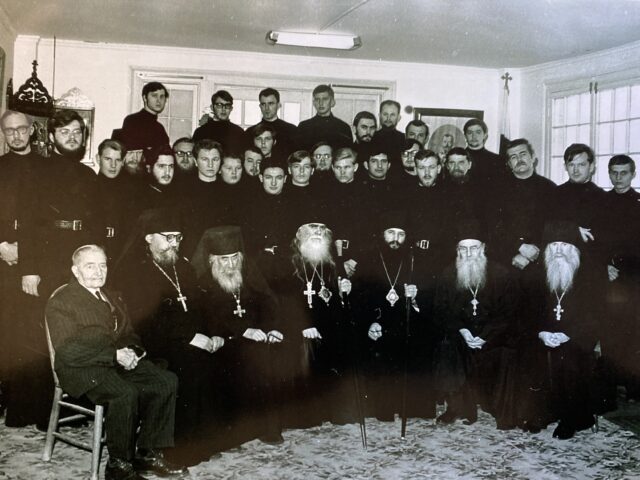

The administration of HTOS with students in the late 1960s, soon after Dana Miller. Photo: HTOS Archives

Despite the fact that you had mastered the language?

Yes. You were working, trying to publish Pravoslavnaia Rusʹ. You were out there doing all this stuff, but nevertheless, you were this kind of growth on the outside of a body. It wasn’t that anybody was negative. Everybody was very nice. It was that I couldn’t identify with a lot of things that were going on there. For instance the preservation of Orthodoxy in Russia, in the Soviet Union, was not something that I could identify with. At that time at Jordanville, the main focus was how to have our brothers in the Soviet Union survive under the atheist regime, which is perfectly legitimate. So we were publishing all this material, hoping that some of it would get back to Russia, etc. This was the main focus of the institution. In my interest, that wasn’t something that I could make a whole lot of sense out of. I think it was important. It was a good thing to do, but not something I could devote my life to. What I was interested in was Orthodox spirituality. That’s a different interest. I came to a point where I couldn’t get anything more out the seminary-monastery connection. So I left. It was probably not the greatest decision of my life, but that’s the way it was.

So I went to this Greek monastery, and that turned out to be a very bad place indeed. But it did at least give me the opportunity to get answers to some of the questions I was looking at, because you had full time access to all the Greek Fathers in Greek. My Greek became pretty good so I was able to read all the Patristic texts that I wanted to. They had a good library there.

Did you find that you could better identify yourself with the people there?

The purpose of the monastery was not to perpetuate belief in some other country. Everybody there, essentially, was a native speaker of English. I would say eighty percent of the people were of Greek origin when I came, but they were basically Greek Americans. There were no Greeks from Greece there at the time. The whole culture was more familiar to me. I was more comfortable. So that was a big plus, but that wasn’t the whole point. If you want American culture you don’t have to be in a monastery. (laughs) Just go out in the streets of New York City, right? So that really wasn’t the point. It’s just that I wasn’t uncomfortable in that sense.

Your main reason was that you couldn’t get more out of Jordanville. It seems to me that the main thing was not that you couldn’t identify, but that you got everything out of Jordanville –

That I was looking for. In retrospect, I can see that there was still more, in a more subtle way. There was still more for me to get, but I couldn’t see it at the time.

I understand there always was an ongoing process where non-Russian-speaking seminarians were considering joining Holy Transfiguration, because it was another opportunity. The same Orthodoxy, but with English language and American culture.

Same Church. Well, the English language wasn’t really a factor actually. I understood Slavonic fine.

So you didn’t care about the liturgical language.

The language didn’t make any difference to me. No difference whatsoever. And at that time everything was in Greek at Holy Transfiguration. They were just beginning to translate into English. There were no English translations. I had to start a whole new liturgical language when I got there, essentially, so I was much better off language-wise at Jordanville. That wasn’t the interest at all. It was more about the focus. Let me give you an example. I think I became a rassophore at Jordanville.

Okay. Fr. Constantine probably was your spiritual father.

Well, he was – sort of. I talked with Fr Vladimir more, even though he wasn’t somebody that heard confessions, at least not at that point. I never really got along that well with Fr. Constantine. Fr. Ioanniki – or John – he was more a of a Fr. Constantine person. I just didn’t connect very well with him.

Dana Miller’s HTOS class with Archim. Joseph (Kolos). Sitting Igor (Kapral, the fut. Metrop. Hilarion), Rassphor monk Daniel (Miller), on the right is V. Potapov (now the mitred Archpriest). c. 1970. Photo: HTOS Archives

So then the question was what I was going to do. And there was this very old monk. He obviously wasn’t able to function anymore, and he used to sew the podriasniki and things like that. So they said, “Well you can do this.” And this was up in the little room way up in the top of the main building, in the corner. “You can do this!” And they took me up there and showed me how to make the little cap and things. I said to myself, “Do I want to do this for the rest of my life? – No, I do not.” There were things like that where I just realized – this isn’t me. It’s never going to be me. Fr. Vladimir was trying to be helpful, but it was hopeless. Actually he was recommending to me that I leave as well.

Really?

Yes. He thought that I would get more of what I was interested in elsewhere. He was pretty frustrated too. He was a wonderful man. I love Fr. Vladimir – a great man. But he realized that, basically, he was running a business. It was a business that had importance, but it was all-consuming for him. He was there from 8 o’clock in the morning until ten at night running the business, and that’s not what he really wanted to do, but he was stuck.

You mean spiritually?

Yes. He could understand that I might not want to just do that. He understood that. He was a very perceptive, sensitive person.

So your memories of him are very fond.

Yes.

He was kind of your person at Jordanville.

That’s right.

So he kind of took care of you.

Yeah, roughly.

If you had any thoughts, then you would refer to him.

I was working with him, so it was easy to…

Right.

And, actually, Vladyka Laurus, at that point, when I came was an Archimandtrite, and he was running the cancelaria [office], so I worked with him too. It was Vladyka Laurus and Fr. Vladimir and – actually, what’s-his-name wasn’t there.

Bishop Peter?

Bishop Peter was around, but he was a seminarian.

Right.

No, the fellow who’s your superior.

Fr. Victor.

Yes, Fr. Victor was in and out. He was more a Vladyka Laurus man than he was a Fr. Vladimir man.

Right.

He followed Vladyka Laurus. I came in the Summer of ’68 – ’67 or ’68, I can’t remember. Then Vladyka Laurus – there was this whole sort of process about whether he would become a bishop or not and go to New York. He was very broken up about it.

He didn’t want to be.

He didn’t want to do it, no. He really didn’t want to do it, and he didn’t want to go to New York, that’s for sure. But he finally did.

Interesting.

Yes. I think part of it might of been – I don’t really know – but part of it might have been Vladyka Averky. He was a little bit – painful. (laughs) He was a nice man, but he was … I think to the monks he was irritating, because he was just kind of, very grandiose and sort of floating around, and so easy-going, and … this was a nice man, but you never got any sense of any sort of monastic austerity or spirituality or anything. He was just kind of …

A prince?

Yes. He was just sort of located there in his own little area, and everybody had to listen to what he had to say, but nobody really cared what he had to say. There was this kind of tension, a sort of “Why is this person here?” sort of feeling. I kind of got the sense that Vladyka Laurus was irritated about that. Actually, what he always wanted was the way he ended up: he could be right there in the monastery, but be the head of the monastery and the main bishop, and have his own monastic thing going. That was his ideal. I think he felt that people like Vladyka Averky just didn’t belong there. If somebody was going to be there, the resident bishop should be somebody like him [Laurus]. I remember having a discussion with Vladyka Hilarion about this. There was a vote about whether he [Hilarion] would be located there. Vladyka Hilarion said the vote went against him. I was chatting with him about this a couple of years ago and he said, “I can really understand this,” because he remembers the Vladyka Averky thing too, and he didn’t want to be like a Vladyka Averky, sort of this figurehead, international figurehead in the middle of the monastery, when they don’t actually mix. So he actually felt that they made the right decision. He felt out of a kind of respect that he should put himself up as a candidate, but he felt that the monks should vote for one of their own to be running the monastery. I think that is a result of the way things were under Averky.

That’s interesting. But you had good relations with Vladyka Laurus?

Yes. We got along fine.

I remember Fr Ioanniki mentioned that Vladyka Laurus was his guardian angel.

Fr. Ioanniki was a good human being with some emotional problems. After I left, I heard that there was trouble, but I never witnessed it.

I understand that also Fr. Constantine’s idea was that in order to become a good Orthodox, in order to get the most, you have to reshape your identity. You have to basically become a born-again Russian – not because of any nationalistic reasons, but just because you would attach yourself better to Orthodox culture, because there is no Western Orthodox culture. Possibly that’s arguable because of what we just mentioned about Kovalevsky. But that wasn’t taken seriously. And there was Fr. Clement Sederholm in Optina – that was a kind of experiment.

I never got that speech from Fr. Constantine, but I never really understood what he was saying, because he was always mumbling.

I think that’s what I got from Fr. Ioanniki.

It could be, he would have known him better. Fr. Constantine was right on him all the time, but I just avoided him.

So you didn’t get this message, basically.

No.

So, being in Holy Transfiguration, you travelled from one world to another . So, did you reconsider some things, like ecclesiology? I think that Jordanville and Holy Transfiguration were not well compatible. You could not belong to both. You had to choose.

When I went there it was part of the Synod. The whole time I was there it was under the Synod. Many times I drove – and I was the Russian speaker – so I would be the go-between and drive Fr. Panteleimon down to Synod and spend time in discussions and things. I was always in on all of that. So, I didn’t really see that much incompatibility when I was there. The only difference was this, and it emerged later: Holy Transfiguration Monastery was basically using the Synod. It was like a cover. This wasn’t admitted, but there was always a sense that we didn’t see eye to eye. “The Russians do their own thing and we do our own thing. They don’t bother us and we don’t bother them.” The system worked well because the Russian Synod did not concern themselves with what was going on at Holy Transfiguration Monastery.

You mean their inner lives?

Right. There was no oversight. So there were always some small differences, but doctrinally and ecclesiologically it was all the same because the Russians were Old-Calendarists, and the Russians respected the [Greek] Old-Calendarists. The Russians’ main focus was on the Church in Russia and worrying about that, so they weren’t really worrying about what was going on in Greece and those kinds of connections. Their main focus at that time was “Are we going to recognize the baptisms of people who were baptized in the Soviet Union, who are getting out of Russia?” In other words, is this really a Church or not in Russia at the moment? Or is it a function of the Soviet Atheist state? So these were the big issues. Among the Greeks this was unknown and they didn’t care. This was perfect for the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, exactly what they wanted. The Russians actually, in most respects, perfectly fitted with the Greek conception of what Orthodoxy should be. There weren’t any difficulties there. It was more about being left alone to do what they wanted to do. That meant basically no oversight. Basically they just did what they wanted to do. I think that led to the split later on, because by then things had gone terribly wrong, and then the church was forced to get involved. They didn’t really want to.

Antony.

Antony, yes, got involved. That was after I left.

Right.

Then they [the Greeks] were horrified: “Oh my God! They can’t do this!” But, of course, they could.

But the problems were there all along, right?

Right. Exactly. It’s one of these political agreements. “We have a gentleman’s agreement that you’re not going to get involved in our stuff.” But the minute that the Synod did, then they went crazy and suddenly said the Synod were heretics, and bad people. They started pouring all the dirt they could possibly find and saying they were perfectly justified in leaving, citing the kind of canons that you just mentioned.

Right.

They never would have done that if they’d been left alone.

Yes. Even after the point that we joined Moscow.

Yes. There were a couple of times, I remember going down – I don’t when this would have been, maybe the seventies. Panteleimon and company were worried about contacts between the Russian Church and the ecumenical movement.

You mean in other Orthodox churches.

Yes. And the reason they were worried about it was that their whole existence, their whole platform was “We don’t have anything to do with the New-Calendarists, the Ecumenists and the Ecumenical movement, all that sort of thing.” They were always kind of worried that the Russians might make some sort of diplomatic moves in the direction of.. they were worried that they would hear that the Russians – well maybe they hadn’t concelebrated, but there was some kind of group and they were present, and what the hell was that. Then Panteleimon would rush down to New York and would talk to George Grabbe and say, “You’ve got to do something about this. It will make us look really bad.” So there was that kind of discussion from time to time. But the Russians were… Vladyka Anthony of Geneva had more of a broad Orthodoxy. So Panteleimon was always supporting people like Vitaly, who were very hard-line and said, “Everybody else is bad. We’re the only good people.” So there would be that kind of politicking. But that was the only real issue. There were no other real issues.

So you left in the late ’70’s?

I left in ’83, ’84.

So just a few years before…

If I remember the history here correctly, there was a guy, Vladyka Gregory, a Syrian.

Oh, Father Gregory, the iconographer.

Yes, he’s in Colorado. So he wrote me a letter after I’d left.

It certainly helped to have Vladyka Hilarion around as a friend. When Vladyka Laurus was in Jordanville, Hilarion was sort of the main person around in New York. We sort of arranged to get my monastic thing taken care of.

Right. So you still feel yourself as a part of the Russian Church Abroad?

Yes.

Really? Very interesting.

I don’t go to church very often, but it’s only because it’s almost impossible for me to do it. I live way up north. I’m very sensitive about the kind of church I go to. If it doesn’t have the right feeling I’m not going to go to it.

What do you mean “north”?

Forty-five miles north of New York City is where I live. So for me to get into Synod to go to church is…

So you are in the country?

Yes.

All right.

I don’t live here, I live north. I’ve always been very sensitive to the aesthetics of Orthodox worship.

From the get-go that’s how you got into this deal.

That’s right.

I see how it is. Very interesting. I really appreciate your time because, for me, it is very interesting to see – I won’t say your life – but, just in a short time, a very significant part of your life’s journey. And you are still an Orthodox, despite all of the tribulation. So, you made my day.

Well, good! (laughs) I’m glad.

The interview was conducated by Deacon Andrei Psarev