This interview was recorded in Sts. Cyprian and Justina Monastery in Attica, a suburb of Athens. I spent a couple of weeks there in the summer of 1998. Fr. Ioannikios and I decided then that the interview would be “for the drawer,” not to be published. I was afraid that the magnetic tape holding the recording might go bad. Last year, thanks to funds donated by our readers, my colleague Ilia digitized the recording, while Olga, a colleague from Russia, transcribed it.

It turned out that the interview did not contain anything that would give cause to keep it “under the bushel.” Fr. Ioannikios, as a monk, said only positive things about his “protagonists.” Another sign of a healthy monastic culture is that he has a sense of humor. The content of the interview is arranged according to the persons about whom Fr. Ioannikios tells.

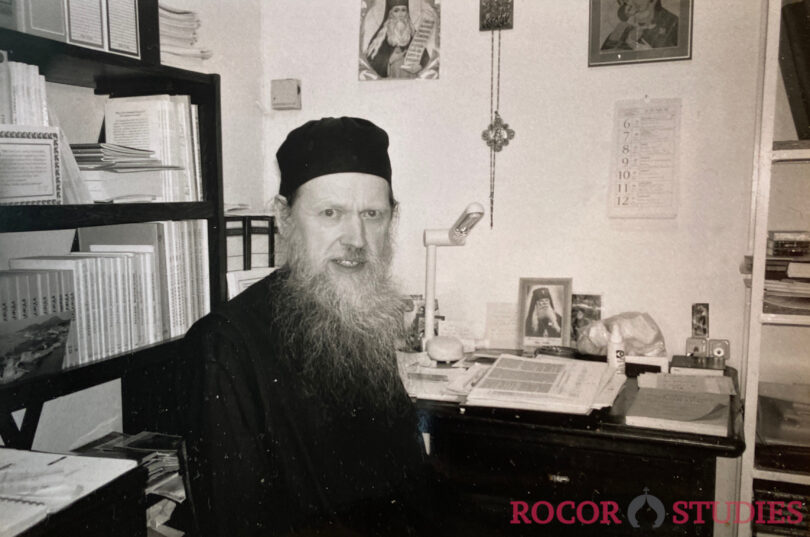

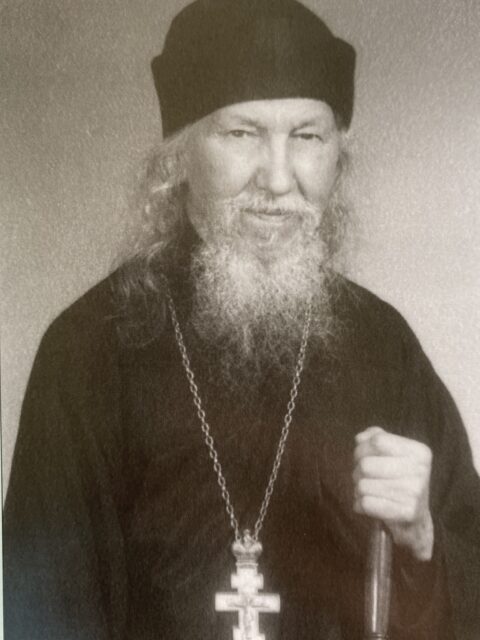

As it happens, very little is known about Fr. Ioannikios himself. At birth, he was given the name Charles. His father was a Protestant pastor. Charles Abernethy was originally from the Greater Chicago region and studied at a military college. Assuming that when he joined Holy Trinity Monastery in the mid-1960s, he must have been just over twenty, he was born right at the end of World War II or shortly thereafter.

At his tonsure, John (his name in Orthodoxy) was named after Venerable Ioannikios the Great (752–846), one of the main opponents of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire. Many graduates of Holy Trinity Seminary remember Fr. Ioannikios as the Seminary Dean of the Students. He also taught Greek.

In 1982, with the blessing of Archbishop Laurus, the monastery’s abbot, Fr. Ioannikios set off for St. Elijah Skete on Mount Athos. He became an Athonite monk and his name was officially inscribed in the monachologion. When, in the summer of 1992, the Ecumenical Patriarchate expelled the residents of St. Elijah Skete for refusing to commemorate the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s name at services, among those who remained legally in the Skete, according to Athonite rules, were the abbot, Hegumen Seraphim Bobich, and Hieromonk Ioannikios. At first, there was an idea to defend the ROCOR monks’ right to live at St. Elijah Skete in a Greek secular court, and Fr. Ioannikios relocated to the monastery of Sts. Cyprian and Justina of the Old Calendarist Synod in Resistance in Attica, a suburb of Athens. However, it soon became clear that these attempts would not be successful, and Fr. Ioannikios simply became a resident of this monastery. In 1994, this Synod, headed by Metropolitan Kyprianos Koutsoumpas (d. 2013), entered into communion with the ROCOR at the celebrations of the glorification of St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco. After this glorification, Fr. Ioannikios was tonsured into the Great Schema and named in honor of St. John.

When I spoke to Fr. Ioannikios in 1998, he had not yet been tonsured into the Great Schema. By that time, most of his life had been spent away from Americans. Fr. Ioannikios mentioned with a smile that family members of his had told him he spoke English with an accent. I was traveling back to Jordanville via Athens. Fr. Ioannikios escorted me to the airport and purchased some Metaxa for Vladyka Laurus, his “guardian angel.” I have not seen him since. I hope that he is in good health and thank him for these recollections of the people of “Holy Rus” in Jordanville.

I want to thank the archive of Holy Trinity Monastery and Seminary for permission to use photographs from it. Thanks, are also due to the Diocese of Australia and New Zealand of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia and to Mr. David Tatge for paying for the text to be translated from Russian to English.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev,

July 16, 2024

I nasmuch as I am not a spiritual person, I would like to ask for forgiveness should this prove merely to be a collection of entertaining anecdotes. Let us hope and pray to Metropolitan St. Cyprian and those among our departed fathers that there be a spiritual gain from it.

Archimandrite Constantine (Zaitsev, 1887–1975)

I set off for the monastery – this was around Easter 1964. I was received into Orthodoxy in Chicago, in the North American Metropolia, during Lent, and wanted to spend Passion Week and Pascha in the monastery. So, I arrived at the monastery on Lazarus Saturday, precisely when the prayer rule [for Holy Communion] was being read, immediately before the All-Night Vigil. My first meeting was with Brother Evgenii [Matseralʹnik], he was tidying something up in the big church while the prayer rule was being read in the lower church. […] He sent me to the office, where I made the acquaintance of Fr. Vladimir [Sukhobok; 1922–1988]. Fr. Evgenii spoke English. I immediately felt a warmth, and they very much drew one in, especially Fr. Vladimir. Even though we did not understand each other one bit, I immediately felt an affinity for him. This was a gift that he had. Vladyka [Laurus] emphasized this at his funeral. After this, they told me to go to Fr. Constantine [Zaitseff; Saint Petersburg, 1887–Jordanville, 1975]. He spoke English. Do you have any idea where his office was? On the third floor, in the new annex. That was where he had his large table, with no photographs, his desks. He had a large desk with a mountain of everything on top of it, and there was a small place to squeeze through, and he was doing something there. Next to it, there was a small sidetable where he had his typewriter, a portable, small one. So, it was there that he typed up his articles, edited them, apart from his cell. This was the editor’s office for Pravoslavnaia Rusʹ. Vladyka Hilarion [Metropolitan, 1948–2022] cleaned it out [evidently after Fr. Constantine’s death] and found all manner of things there. Once, I went to him in the evening, he was glowing with contentment. “Oh!” he said, “What a joy! I cleaned up my desk today!” – and pointed to that small space that had grown a bit larger, while next to it there was still that mountain of papers and suchlike.

Of course, he told me about how he was born in Saint Pete’. I do not know – some people had the opinion that his family was – as I recall, at least on one side – baptized Jews. He grew up on Nevsky Prospekt in Saint Petersburg. Speaking about his youth, he told us once that he was baptized as Kirill Iosifovich, in honor of Cyril the Deacon, a martyr, whose memory – I cannot say when it is kept. It was not the Slavic Cyril or Cyril of Alexandria, but there is a Deacon Cyril, a martyr, whose memory is kept with that of other martyrs. I do not remember now what year that was, but he said that once, on his names-day, he came to his lesson, and there in the grammar school… and at that time, mind you, everybody would greet people on their names-day. He said that none of the students greeted him, and none of them said anything, as if everything were normal. And so, he said, I went home, and at home, there was a greeting card from each of his fellow students: they had sent them by post and not said anything during lessons. So, there was such an event. And so, it happened once that there was one teacher whom he especially loved, and he invited him to lunch. That was something, of course, totally unprecedented. And, he said, he came for lunch. His telling me about this, of course, to me as an American did not seem especially wild… but at that time, it was totally unprecedented.

As it were, a violation of barriers?

Unheard of: a teacher going to a student’s house.

Well, quite. And his mother was called Florida?

Yes, so it would seem. If I am not mistaken. The name was in his book of commemorations. And he spoke once about a certain house. It seems that there was a large household there, not just mom and dad, but all manner of kith and kin. There was also a patriarch of a grandfather, who, each evening, would make the rounds of all the rooms in the large house in a nightshirt, lighting the lamps [in front of icons]. And, he said, he once went into a particular room, and there was a young officer in the household, and all the youth were there, at some kind of party. There was a gathering of this sort. Merry young officers with a completely different spirit, and then grandpa comes in with a wick wearing a nightshirt to light the lamp. He must have described it vividly.

His wife was a famous Armenian lady [Sofiia Artemʹevna née Avanova, Saint Petersburg, 1899–Shanghai, 1945]. He said that he had been sent to Heidelberg to study political economy. And then, apparently, Fr. Gavriil (Egorov) said that he had borrowed his language, his literary style from a political economist, whose name he knew, that he had borrowed this manner of writing from him [i.e., that Fr. Constantine followed German syntax in his writings]. He finished studying here and returned to Russia; he had some kind of position in the Senate. He gave a description of this somewhere. Something between the departments… as I understood it, he attended ministerial conferences as an intermediary. Once, I tried to talk in Jordanville about what kind of work he had there, but they understood it in a different sense…

From left to right: future Archpriest Rufus Tobolov (d. 2023), Rassophore Monk John (Abernethy), Archimandrite Constantine (Zaitsev), George Kochergin, Gabriel Tobolov. Newspaper photograph from Utica, NY, June 13, 1969

Fr. Michael Pomazansky said about him that Fr. Constantine always knew how to say and to do that which one did not expect. Indeed, he did. He was no longer serving when I entered the monastery: he had been ill before then and had ceased serving. He served when I was there. He concelebrated when I was ordained and led me around the altar.

Was that Vladyka Averky who ordained you?

Yes.

Of course, he [Fr. Constantine] was always in his office, and he impressed upon me from the outset: “Any time you need, come by.” Sometimes, I had to take him up on this offer. Indeed, there were times when I had to wake him up at night, at the most inconvenient of times: he would always get up without any issue, welcome me in, hear me out, and tell me what I needed to know. He had this in him. Few people saw it. Most people saw him as an ideologue and intellectual. I think that few people got to feel this warmth, this love that was in him. There was a lot hidden behind that Petersburg, pre-monastic [façade]… He did not have that many spiritual children. As I said, Fr. Nicholas Tkatschow, and Vladyka Hilarion, who is closest of all to the monastery now. The others may already be in the world beyond, through you might yet find them. There is the Petrochko family. The head of the family was called Nikolai, also a devoted spiritual son. Her sister, too. He fell very ill and almost died, and after that he was still entirely handicapped. Fr. Constantine, although already in old age, despite his heavy workload, still traveled to them at critical times to give them Communion, prayed for him, showed great concern.

I remember that we had a baptism in the monastery. I was at the baptism, just to sing, to be in attendance. I think it was one of the children of Father Vsevolod Drobot. Then I went over to him [Fr. Constantine], invited him to the guesthouse [for the reception] after the baptism. He said: “No, we are going to the church for a prayer service.” And indeed, they went and sang the service. So, he had this in him.

I’ll tell you something more. In the cell where I lived, there was an old postman, Georgii Ivanovich, who lived next to me. The seminarians called him “Jet”. He was, you see, a former taxi-driver from Paris, probably from White movement, one of those who ended up abroad. He was pious. He never wore a cassock but worked in the monastery as a driver. He had a stroke later and lay paralyzed in his cell. People looked after him. I remember – I was living next door – that Fr. Constantine would come to visit him every day, and I heard him reading prayers for him. He would be lying there; one could not say whether he was conscious or unconscious.

Where was your cell, Father?

It was on the fourth floor next to the shower. Right next to where Fr. Laurence [Campbell] was.

That means it turns out, between the shower and Fr. Laurence, closer to the shower.

Yes, probably. I lived there when I was studying at seminary. After seminary, I was sent to live in the seminary wing.

As a teacher… well, in class, somebody was always reading lecture notes that would later be published as a book. These were lectures that he compiled. He would correct the person reading, stop him, and add something. After this, there was an exam. He was always very strict in exams.

Strict, you say?

He always had some particular expressions or precise words that he wanted you to say.

And these notes were enough to last for a semester?

Yes. And Fr. Constantine did not give out As. Some Bs, and much further down the scale, and there were many who simply did not cope with the exam at that time, and then had it moved, hoping for mercy.

But at the end of his life he was mollified a lot. I remember other courses with ‘A’s all around. He would say at the exam: “Oh, such good students, everybody gave such good answers.” Many people have observed that people’s true nature somehow manifests itself in old age.

Yes. So, as for all this strictness – you might think he had something else in his heart. It turns out that this was a near childlike kindness. Even though he was very strict and demanding in many respects, he did not suffer disobedience. If he said something, then he wanted it done exactly as he had said. If something was not right, he would tell you.

Quite definitely. Did you speak English or Russian with him all the time?

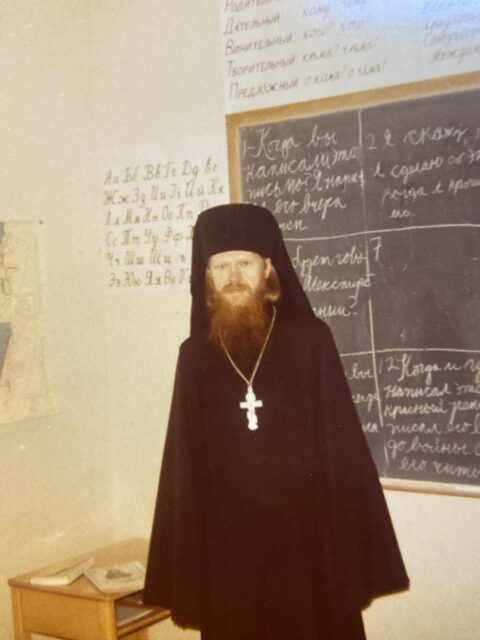

Fr. Ioannikios in a seminary classroom

The first thing he told me was to forget about English. He demanded that I read only in Russian, not in English. There was a young man who helped me to get started. Five or six weeks passed, and he stopped me after Compline. He asked me something, and I did not understand, asked me something else, and I did not understand: “How are you doing?” – “Fine.” – “You need to work on your Russian; you have to feel a need for it.” And after this scolding, thank God, I am very grateful for it now… And I remember when we arrived when I started… I was there for the first time at Pascha 1964, entered the monastery, came to stay, when they buried Metropolitan Anastassy in 1965. At Pascha 1965, I returned to the monastery and ended up staying there until 1982. The first thing I did was to start studying Russian. Fr. Constantine had knowledge of languages: English, French, German, could read and speak fluently. He had the idea that [a dictionary needed to be compiled] with untranslatable words. Even though he had himself started [the publication of] Orthodox Life. He could speak English, but he required that those who could study in Russian, and especially Russians, that they did so, in order to preserve their own language. He emphasized that father Kliment [Sederholm, 1830–1878] of Optina, who was German, that they at once tried to Russify him, to make him Russian. The same was with Vladyka Averky. This was not any sort of narrow-mindedness or chauvinism. They simply realized: in order to understand Orthodoxy, in order to enter into this life, you cannot enter into it, that generation, without the language. You can consider that this is why I ended up with these obediences: because I could write in American English. At this time, there were not many people in the monastery [who could write English fluently]. There was Fr. Georgy Larin [1934–2024], but he was kept occupied in the seminary. So, thanks to God for everything, and I am very grateful. I will also say a bit more. When I was in Russia – two times by now, especially the first time – let’s say, when I was still at the airport, in the airplane, the whole of post-Soviet society was bewildering for me, strange kinds of people, totally incomprehensible. Everything was foreign. It was only after getting there that I met people like us, church people, genuine people. It was then that I felt at home, I was amazed.

As if you had ended up in Jordanville, or not?

Not quite as in Jordanville. Fr. Constantine called Jordanville a “little island of historical Russia”. As if within Russia itself history, Russian history, had ended, and continued here in some way.

This is somewhat reminiscent of the Old Ritualist view. They thought that history had ended with the last Tsar, Aleksei Mikhailovich, when he adopted the innovations.

He told me that he had been at services with Fr. John of Kronstadt, had seen him, venerated him greatly. He gave me a copy of My Life in Christ in English. He simply said that this was a book by St. John of Kronstadt and I should pray to him. You can open the book and receive guidance from him.

That is, simply pray to him and read?

Yes. There were occasions when we did this. Though various fallacies are possible here, too [lest one get into a kind of bibliomancy]. He had a copy of the icon of Our Lady of Kazan in his cell. He did not have anything fancy in his cell, everything was simple, had been purchased many years previously. I visited him in his cell several times, for confession or another reason. The gaze of the countenances on the icons looking down. A small, silver frame with not entirely traditional iconography, I do not know where from.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev: When I was editing this text below about the Jordanville archimandrites, I remember that I was told that Fr. Kiprian (Pyzhov) called them the “fire brigade” because of their yellow mitres.

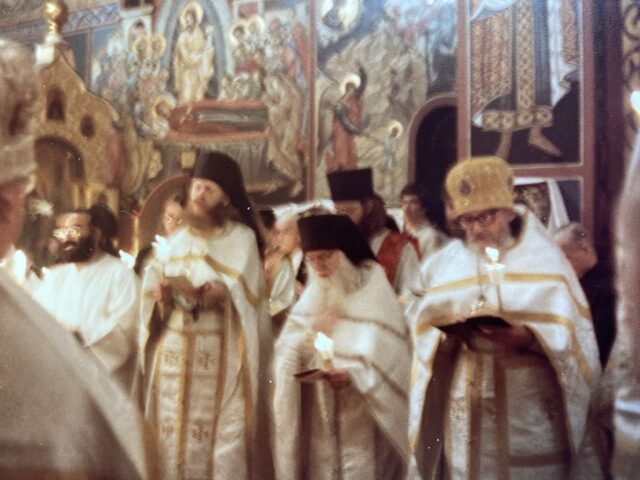

Fr. Ioannikios, Fr. Vladimir (Sukhobok), and Fr. Sergius (Romberg) at Paschal Matins

Fr. Panteleimon, Fr. Iosif, Fr. Constantine, Fr. Michael, Fr. Polikarp, Fr. Antonii, Fr. Kiprian. It was Lent. We were getting Pravoslavnaia Rus’/Orthodox Russia ready for mailing out [i.e., in the process of putting the journals into envelopes]. Somebody brought us a record with Greek Byzantine music. Fr. Constantine was upstairs [the distribution was on the second floor of the monastic dormitory]. Then he came in all indignant, not even able to speak: “Have you lost your mind?” He was looking me right in the eyes. “It’s Lent now! In the monastery! You have put on this jazz here?” We brought it for him to see, but still turned it off to be on the safe side.

He was in the White movement, yes? You mentioned, as an intendant?

Yes, he said that… it is evident that he was not involved anymore. He was also very upset that the Sovereign’s abdication was greeted like a holiday, that there was such national jubilation among all people. He considered this to be a great sin of the Russian people. [inaudible; referring to his service:] It was something in logistics, I think.

Did he give any kind of spiritual guidance? If one can talk about this at all, that is.

He gave me the Instructional Notice [Uchitelʹnoe izvestie] at the end of the Sluzhebnik before I was ordained a deacon. And before my tonsure he gave me a book by Bishop Peter [Ekaterinovskii, 1820–1889, Ukazanie puti k spaseniiu. Opyt asketiki / Guidance on the Way to Salvation: Ascetic Experience].

In Jordanville, the custom was that a newly tonsured monk would stay in the church for three days, then come and serve the brethren during the meal, wearing his mantle and klobuk. But for some reason I was ordered to stay in the church, not to go to the refectory. I was tonsured on the first day of the week of the Triumph of Orthodoxy, after the first week of Lent. I was in the church until Wednesday of the second week of Lent. Brother Igor, a seminarian, now Vladyka Hilarion, brought a little food. And I realized it then. I think there was a whole conversation, the brothers came, everyone was yelling: “Father Ioannikios isn’t coming to serve the brethren!” Vladyka Averky: “This is a Ukrainian custom.” I don’t know what happened there, but it was not granted to me to serve the brethren.

But were you the only one to be tonsured? Yes. There was a long period of time when there weren’t any [tonsures].

And what was your baptismal name?

John. In honor of John Climacus. Much like Fr. Joseph, the co-founder [of Holy Trinity Monastery] along with [Fr.] Panteleimon. He was also John in baptism. He also treated me with affection.

We left off with Father Constantine. Is there anything more you want to tell?

You asked about his guidance. This is, of course, deeply intertwined with personal confession. Yet there are some things that can be said. First of all, there was a moment when almost all of Eastern America was without power. It was winter. This was during Vespers and Matins in the church. It was already dark. I went up onto the choir loft and saw that Fr. Constantine had also arrived. This was the first mass [power outage] and it passed quietly, people helped each other…

This was, maybe, in the 1960s [November 9, 1965]. Then it went away, and all manner of outrage started [July 1977]. I remember that Fr. Gurii and Fr. Constantine always came to the altar in the morning and read the books of commemorations, prayed. He always stood on the right choir loft, prayed very fervently: from the beginning of Compline and the Midnight Office. He evidently suffered from insomnia. I remember that one day, after the liturgy, when he was already very old, I went to have breakfast and to see him. “Fr. Constantine, the liturgy is over.” “Well, praise be to God, praise be to God, I haven’t slept so well in ages.” He was so happy that he had managed to sleep well. But he would, of course, always serve on feast days, on Sundays. Also, one time, when he was already elderly, he came – I remember, I was serving – it was at the beginning of the Midnight Office. Maybe it was on a Friday. When he was venerating the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God set in glass, he fell and the icon fell on him. It broke a bit. He stood up with help from others, went into the altar, but he was already sitting down, not standing up. He received Communion during the liturgy. Some people helped him to his office. He kept on working, but only sitting down; he could not walk or stand up, he could not lie down: something hurt. But he did not want to see the doctor, saying: “They will ruin what I have left. In old age, everything is ruined anyway, and the doctors will ruin whatever is left.” But on Monday he ultimately relented to call an ambulance and go to hospital. Vladyka Averky was with him. He was sitting in the ambulance. The post had come just before, so he was sorting through his post along the way, attending to his affairs. He was brought to Saint Luke’s Hospital in Utica and immediately taken to be X-rayed; it was already painful for him to lie down on the cold surface.

Were you with him?

Yes. So, several of his ribs were broken. He said that they were “legitimately sore”. They gave him some corsets and put them on. Somebody was there at all times in the hospital, and then they gave him an ambulance and transported him back. He was as strict as ever. I remember him saying: “All these old people whom I know were entirely different… and our generation is completely… I considered the older generation whom I knew to be real people.” He frequently repeated ora et labora (“pray and work”). He complained that his prayer life was impeded by his work as an editor, his intellectual work. When I only just came to the monastery, there was a seminary ceremony. And I did not go, out of my novice’s zeal. There was a representative of New York Diocese at it, a priest, who gave an address. Fr. Constantine said: “I didn’t see you there for some reason. You should be at all monastery and all seminary gatherings, without exception.” For this reason, immediately at the outset, I considered it my duty to attend all services, all gatherings, all talks. I found out right away that what they instituted there in connection with the [monastic] communal life had to be adhered to strictly. Although communal life in Jordanville is not so strict in a spiritual sense. Well, after all, this old generation had a great love for Russia, a great love for the divine services according to the typicon, as Vladyka Averky has, and for traditional Church Slavonic. Fr. Constantine, too, loved church singing and told me when I became attached to it: “You are to conduct the services as usual, without getting distracted by new hymns or melodies, so that people can pray without getting distracted by mysticism.” Well, he had some apprehension. It’s hard to reconstruct now. Well, the most important thing is to pray, to focus on the words of prayer. He did not give any special rules, there were common monastic rules. At that time a lot of the boys were interested in the Boston monastery [of the Holy Transfiguration in Brookline, MA], because there, of course, everything was according to the rules, they confessed their thoughts, read the Jesus Prayer, and listened to their elders. It was like that when the monastery first came to the Church Abroad, it was very positive. Fr. Constantine never… He was wary from the very beginning. Several times, he said, “I knew a man who was very much seeking the spiritual life, he had an elder and mentor [at New Valaam in Finland], and they agreed that they would move to Russia, go to a good monastery, the elder said: ‘I will go there first, and then I will write to you asking you to join me.’”

Was it one of those?

Maybe one of the ones from Pechora [the Dormition Lavra, where some of the Valaam monks who returned from Finland after World War Two settled]. And he said, the elder went there: among the icons there was a portrait of Stalin. Ultimately, his spiritual child received a letter from the monastery, from his elder, saying it was okay for him not to go there. So, he thought that it was not necessary to be carried away by this, so to speak, high spirituality, to sacrifice something for it. After all, there was a sober attitude in Jordanville.

Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky (1888-1988)

Father Sergius [Romberg, 1920-1992], I remember, stopped me once and said, “You know, Archbishop Vitaly of Jordanville, Metropolitan Anastassy – they were not particularly ascetic. But when they served, you could always feel the presence of grace during their services.” This is modesty – not to get carried away. Because I was very close to some Americans who got carried away by Boston [Holy Transfiguration Monastery], and then left…

By the way, the first time I saw Vladyka Cyprian [Chairman of the Synod in Resistance] was, I think, in the ‘60s. He was brought to Boston. Metropolitan Kallistos [of Corinth 1906–1986] was there. And he said, “monasteries are built by miracles.” He was very simple and direct.

Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky at his home

I was also [close] with these people: Father Constantine, Vladyka Averky, Father Vladimir, with whom I worked most of all, because I had my obedience in the chancery. Vladyka Laurus – I always had close contact with him, it was thanks to his intercession that I was accepted into the monastery, he always took care of me. I am very grateful to him. And Father Michael Pomazansky. He lived with his wife. I used to go to see him. And when she got sick, we had to put her in a care home, and he moved to the seminary house. But, he, of course, was a completely different person [than Fr. Constantine]. I remember when we were studying and some of the seminarians had a theological question, a dispute, and I approached Fr. Constantine. Fr. Constantine was standing during the break between classes with Fr. Michael. I came up to him: “What should I make of it, Father Constantine?” “This and that.” And how so? So purely logical, definite… “yes and no.” Father Michael stood there like that, he had a kind of sly smile, his eyes glimmering, and he stood shaking his head, rubbing his hands, and somehow, he was silent. He said something very vague, but it was evident that he had something in his head that he did not want to tell us, especially in the presence of Fr. Constantine. Well, Father Constantine is Nevsky Prospect, Saint Petersburg… And Father Michael is the parish, village clergy of some kind. He and his wife – they were very special. His wife was the same. Vera Fedorovna. She suffered greatly from arthritis. Going to see them in this house – it was a special kind of grace. “Father Michael, Father Ioannikios is here!” “Oh, Father Ioannikios!” – and came out himself to greet. Two pictures were hanging there: one on one side, one on the other of the front door. They were both old. One picture was of cranes coming up from the lake to fly back to Russia. It was signed at the bottom… And on the other side: a gate, some naked dead trees standing without leaves, a miserable swamp. It said… It was a kind of instruction. And, of course, she would always say: “Father Michael”, back and forth. Modesty, peace, tranquility. And there were all kinds of questions: “Father Ioannikios, what do you think?” – he would always ask. I had to figure it out for myself. And he gradually got onto the subject: “How about this? Don’t you think that…?” – and tried to give guidance.

He spent his whole life fighting the Parisians [theologians associated with St. Serge Theological Institute in Paris –ed.].

It is very good and compelling to argue things, but you must not see it through to the end, so that your opponent does not rush and has a chance to correct [his error]. “Several times in my life,” Fr. Michael told me, “I got to meet people whom I had written against. ‘Well, Fr. Michael, if only you had drawn the conclusion out of what you wrote, you would have put me utterly to shame.’” And there he was thinking to himself, of course: “Well, that’s why I drew the same conclusion that you did yourself.” So that was very typical of him.

“I,” Fr. Michael would say, “was the last in the family, always had poor vision, was always falling behind. [When] I was sent to school, I was several months younger than the other children.” Well, Misha was always the smallest of all.

When [Fr. Michael] was 90 [in 1978], they threw a party. Students came. There was a solemn service, after which Fr. Michael was honored. Speeches were made. Then Fr. Michael got up [and said]: “How embarrassing this is! It’s the feast of the Archangel Michael, yet all the attention is focused on me. I just live here at the monastery, but you, parish priests, you are the ones who work hard and labor, and bear a burden.”

I remember I went to see him once and he said, “Oh, Fr. Ioanikii, I can’t see, I can’t hear, I can’t speak. I can’t work, but I am ashamed to ask for anything.”

Then in the same breath: “In my time, I passed through all the schools of the old Russian Empire. I went to Klevan Theological College, then Zhytomyr Theological Seminary under Metropolitan Antony [Khrapovitsky, 1863–1936], then Kiev [Theological] Academy. I got the most out of the theological seminary.” The rest was as followed… [When he was at] the academy, those were the years of the revolution. Later, he told me that it was in 1905 that he was at the seminary. Only recently had a new seminary building with electric lighting been built. Everything was state-of-the-art. And they decided to rebel. Everybody was rebelling. Fr. Michael made it to a secret meeting only once. He was dragged somewhere through back alleys behind fences. Something was being discussed there. There was a revolt the next day. They broke the electric lights and windows. Running back and forth, screaming. Troops came. “Everyone to your cells!” (there were two to a cell) That was the order: everyone was to stay lying in his bunk. And there was a soldier with a gun in every room. Then, everyone was expelled from the seminary. It was possible to apply for readmission. He was, of course, readmitted to the seminary. He graduated and went home [to the village of Korystʹ in Volhynia Province]. He was advised to apply to the [Theological] Academy. “Why should I apply to the Academy? What do I know?” His father advised him, “ ‘Let’s read the Gospel according to Luke together.’ .My father and I read the Gospel according to Luke. I went to Kiev. The questions on the exam happened to be about the Gospel according to Luke. I responded, and I was admitted.”

His father was a priest. There is an article about him. Fr. Michael left behind his own reminiscences. Then, [Fr. Michael] said, in his last year at the Academy, he composed a homily of his own on the basis of some homily by St. Philaret of Moscow and he was appointed a missionary somewhere in the south. But that is, of course, something altogether different.

He had relatives in Poland and Belarus. He was ordained at an advanced age [38 years in the Polish Orthodox Church].

Fr. Michael always used to say about the services: “I can’t see anything, I don’t understand anything.” I was on the left choir. At the Dormition, a Deacon who was a seminarian appeared. You know, on feasts of the Mother of God, there is one and the same prokeimenon, only the verse alternates. He read the prokeimenon, only with the wrong verse. Fr. Michael shook his head: “Wrong verse!” I said: “Fr. Michael – he can’t hear, he doesn’t understand!”

Priestmonk Seraphim (Rose, 1934-1982)

Turning to Fr. Seraphim Rose: I met him in Plymouth. When I came to the monastery, it was Metropolitan Anastasii’s funeral and St. John [of Shanghai] was there. After the service and the meal, I saw that Vladyka John was standing there with a young man who was able to translate for him. That was his last time in the monastery and the last time that I saw him. I did not speak Russian. I approached him and said: “I am an American, I would like to try it out in the monastery. But I have heard that all of the Americans do not make it, so please pray for me.” He said, “Of course, I will pray, but you have to try yourself, and, by the way, in San Francisco, we have a young American who converted to Orthodoxy. You can correspond with him.” That was Eugene Rose, who was there with Gleb Podmoshensky. They had just started out. And I wrote a letter to them straight away. We had sporadic correspondence. And this was always a blessing of sorts.

When he was already a hieromonk, he came and spoke with the seminarians. He was at the monastery for 2–3 days and then at various parishes. He came on the train so that he could look at the winter landscapes. On the train, Fr. Seraphim had gotten to know a young American man after seeing that he was studying Russian. He got interested: “Yes,” he said, “here in America, I see that everybody who goes to church is a hypocrite. In Russia, religion is being persecuted. Those who go to church suffer for doing so. And for this reason, I want to study Russian, go to Russia, and meet true believers.”

Once, I went to see him in the evening, and we spoke about various topics, and then he went on his way and returned to California. He happened to die just at the time when I was away. He describes this trip in that book.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev: Here, Fr. Ioannikios, in defending the monastery in Jordanville, is obviously replying to the following entry about their meeting in Fr. Seraphim’s diary: “December 11/24, 1979. After the Vigil Fr. Ioannikios visited me in my cell (he had conducted me to the cemetery on Saturday) and told of some of his sorrows and difficulties. Truly he has a difficult time and is not getting the spiritual help he needs.” (Hieromonk Damascene, Father Seraphim Rose: His Life and Works, Platina, CA, 2003, 864).

Talking about these books, they [say they] receive spiritual succor. [indecipherable] I hold nothing of the sort to be true! “Ask and it shall be given to you!” Anyone who is spiritually minded and prays will find what he seeks. We have seen this in saints’ lives, Paterica – how many examples there are! There were different kinds of monasteries. Ignatii (Brianchaninov) writes about how to bear oneself under different circumstances. One must look for people [probably: spiritual instructors]. Inasmuch as I did not have the spiritual mindset that was needed, I also did not seek that which was needful, with the consequences being as expected.

Hierodeacon Gelasii (Mitusov, 1890–1966)

When I came to the Monastery, Hierodeacon Gelasii was [there]. He was a Don Cossack. His tractor was called “The Horse”, because of how he rode on it. He always had boots on. He was tall. He was already dying from leukemia. He had his own “hut”, where Vladyka Laurus’ skete is now. Vladyka Laurus used to help him. What is left now is the new house, but there used to be a wooden one and a whole homestead there, such as only a Cossack could have. He had everything there, he had bees, produced honey, kept a garden, apple trees, all manner of berries. I would help out in the mornings in the office. Fr. Laurus was there, while Fr. Vladimir managed the bookstore. I would help pack the books.

After lunch, I would be sent to Fr. Gelasii. I was only just starting to speak Russian at the time. What a shame! Because he would sometimes have me take a seat and tell me about things. He had a very rich life, because he had lived through – in the first version – beginning in the 1920s – a great deal. He had been imprisoned for his faith. When he had returned from the camps, he did not have a wife or children (he had had a large family). Nobody was there. He only found one of his sons later in Italy amidst the Vlasovites. The second summer that I was working there [with Fr. Gelasii], he was already dying. He was also a spiritual son of Fr. Constantine. Fr. Constantine would go to the place where Vladyka Lavr lives now and give him communion. We buried him. After the funeral, Fr. Iosif [Kolos, one of the monastery founders] stood up and said: “We could not speak about his life. Fr. Gelasii evidently knew when he was going to die and showed three fingers, so as to say: in three days. And he told us about how, when he was in the camps in Russia, they were out logging and, of course, were dying. They were cutting wood in the winter, and he felt that the end was near. He fell onto the ground and began to pray for the Lord to take him. His name was Dmitrii, after the holy right-believing Tsarevich. And then there appeared a noble-looking elder, who said: “Dimitrii, arise!” He gained in strength, held out etc. etc. [there were many miraculous moments like this in Fr. Gelasii’s life].

After the war and all these transfers and handovers, he ended up in Munich – he found the monastery [indecipherable]. Metropolitan Anastasii was there. He was brought to see the Metropolitan. He fell on his knees, weeping. He saw the Metropolitan and the elder who had raised him from the dead in the camp. It was there that he entered into monasticism.”

He sat me down and da-da-da [rapid speech]. “I don’t understand!” Brother Ivan said: “Go eat honey!” “That’s something that I understand.” Then we were gathering currants – one for the mouth, one for the basket. That’s the way we were gathering. He was taking the jars, filling them with currants, and pouring honey over them. “Take this with you.” How he spent the winter there, I do not know. The winters there are harsh. He toiled. He was no longer serving and was gravely ill but forced himself to work.

Various Personalities

I recall another moment with my neighbors in the monastery. At the time, they were pension-age, mostly those who had escaped being handed over [forcibly repatriated to the USSR after World War II], moved to America, and [told of the miracles of their life]. One of them, a humble fellow, would always cry at the Liturgy. He was at war with his neighbor. He was very humble, but there was no pleasing this neighbor of his, least of all through humility. And he said, “When I come to the church, I see these young Americans and I think that this is all strange and foreign to them, but they come, nonetheless. And I cry.”

I came to the monastery and was there during an ordination. We assisted Archdeacons Pimen and Gurii and Hierodeacon Ignatii. They were ordaining Monk John (Melander) as Hierodeacon. He [Fr. Pimen] was also from the Catacomb Church. He even left something behind an altar crucifix.

There is an icon there of St. Barbara on the wall in the upper church, on the “women’s side”, between the windows. Every evening after Compline, Fr. Pimen would go and stand in front of the icon of St. Barbara. Once, he went to Syracuse to serve with Fr. Sergius, and he suffered a stroke. He was taken to hospital. After the liturgy, Fr. Sergius came to the hospital; he was lying there unconscious, but had still taken the Holy Gifts with him. “Fr. Pimen, do you wish to have communion?” He opened his eyes and somehow communicated that he did. He was communed and passed away several hours later. They say that St. Barbara helps one to have a viaticum before death.

In [my] first [summer] in the monastery, the academician died who had built this house and taught in the seminary. He had been collecting all manner of information on monasteries in Russia, while I had been doing so on ascetics. He happened to be a baker. He was meant to bake a stock of break for the cold, autumn period. Fr. Sergius said that he had already put the bread in the oven and [stayed there] to wait while the bread was baking; he had heart problems and was deaf and they found him there. He died while carrying out his obedience. That was [my] first funeral.

Archimandrite Polikarp, for many years he was a secretary of Metropolitan Melety (Zaborovsky) of Harbin and Manchuria (d. 1946)

Fr. Polikarp [Archimandrite, Gorbunov, 1880–1970] fell ill and was in hospital. They thought that was it. After coming back [to the monastery], he would sit in his cell and pray. I went to see him three times. He would be reading the service for the departed and crying. We brought him something to eat. And he spoke about how when he was in hospital and waiting for death, he heard such wonderful, beautiful chanting that he said that if the chanting were to continue, he could not resist and would depart from his body. “I was frightened and started praying,” Fr. Polikarp said. “O Lord, give me but three three years for repentance! St. John of Cronstadt, pray for me.” Up until then, he had been sociable, but after that he would rarely go out. When he had the strength, he would go to church.

Vladyka Nektarii would come from California. He was hugely tall but calm and quiet. I always loved him. He was a spiritual figure. Vladyka Nektarii was always very open and interested. He was warm. It was somehow natural to be with him. By the spring, he was sitting below the apple trees.

There was a servant of God named Vasilii Skorikov, of whom one could take different views. He used to work with Leva [the layworker Lev Ivanovich Pavlinetz] in the kitchen. He came up for a blessing. Vladyka blessed him.

“What is your name?”

“Vasilii.”

“Where are you from?“

“Voronezh.”

“How are you being saved?”

“We are living, [indecipherable] and praying.”

He spoke about how Vladyka Tikhon [Troitskii, of Western America, 1883–1963] was buried. He had passed away before I arrived. People always spoke about him with the utmost respect and reverence. “My children!” He had retired to the monastery.

Vladyka Nektarii was a [spiritual] child of Elder Nektarii, and that of Tikhon in America. He said one had to suffer “to sleep a bit too little”. Vladyka Nektarii was always traveling.

One time, a few people came together. They got together once and sat in the chancellery with Fr. Vladimir. Vladyka Nektarii was telling of Elder Nektarii. He had a special presence. A very interesting man. He smiled when joking. He had an imperturbable calm. His vestments were clumped together with tacks.

Vladyka Antonii of San Francisco was also in Australia at the time. Once, he came and all the Australians remembered him.

Also, during my first year, there was a certain Fr. Vladimir Evsiukov. He was completing his seminary studies and looking after the Summer Boys [i.e., the teenagers who would come to the monastery from various places in the USA as part of a summer program]. He began to doubt what he should do: join the monastery or marry. He decided to return to Australia and became a priest there.

HTOS Class of 1981. Right to the left, with their current positions: Archpriest Serge Lukianov, Deacon Gregory Dobrov (d. 2015), Mark Medinsky, Constantine Pavlov. Faculty: Bishop Luke, Metropolitan Hilarion (d. 2022), Archimandrite Theodosius (Clare), Schemahieromonk John (Abernethy)

Archpriest John Stukach, from Sydney. When he was at seminary, he was a choir director, a good one. Fr. Alexander Mileant was getting married. His fiancee had come from Argentina. A choir of seminarians was assembled to sing at the wedding. Fr. John was the choir conductor. Vladimir Evsiukov was singing bass. I was put on first tenor. There were several rehearsals. Fr. Ambrose (Toshevich) even remarked that he considered the wedding not to be a serious matter. I told him the wedding was on Sunday. We went there to sing. There was a reception in the parish house. Some locals thought it was boring. They were sitting there modestly. Something [evidently the traditional exclamation gorʹko ‘bitter’], and they blushed. After the meal, the seminarians had rooms to themselves. I heard a conversation and that they are singing somewhere. It was the Cherubikon and other hymns. Each according to his taste. Then they came back. And then I had to wash the dishes out of turn. Then [indecipherable] “ah, you sinners!” For going to the wedding. I did not have to (being a novice).

They hung on the bulletin board in the morning before class, after a second or third period: “It is not appropriate for future servants of the church [to attend a ball – indecipherable].”

Those were still seminarians from the DP camps, who had been born before the war or during the war and underwent all sorts of things. They graduated from high school in Australia or America. They were grown-up in spirit. Then came those who had grown up in the West in comfortable conditions. And the generation now after this is altogether different.

We had still studied in the old building, in the classrooms. Upstairs was a large, shared dormitory at the end of the corridor. That was freshman year: everybody was together in one room, and then from sophomore year on, they were in separate rooms or two to a room.

We had a large freshman class, and then the number of students decreased.

When Vladyka Averky fell ill and was hospitalized, it was our turn to keep watch. It was Fr. Irinei (Roshon), myself, and Fr. Hilarion (Kapral). It was always someone’s turn. Once, I was there. It was Sunday of the Holy Fathers, and we were reading the Typica briefly. I did not have the Praxapostolos, I was just reading [the text]. Forgive me, Vladyka, I don’t know the verses at the Alleluia. “Ah,” he said, “use your brain!” “If only I knew them?!” Then he told me the first and second verse. So, I sang the “Alleluia”, while he sang from memory. He knew the New Testament, because he taught it for many years. He probably knew it by heart. Once, he came back totally satisfied! He had been at some parish feast in New Jersey. There was a meeting there after the Sunday festivities. Then they served Vespers and asked Vladyka to hold a discussion with the parishioners. Some Russian Baptist had come to the discussion. When the discussion started, the Baptist came forward and started quoting [Scripture]. But he got into it with the wrong person. Vladyka said, “So, the Apostle Paul says such and such.” “Yes, yes!” “But read on.” Well, he shamed him in front of all of the parishioners. Vladyka Laurus was his driver at the time. Vladyka Averky was, of course, masterful. In the hospital, he and I read The Journeying of the Monk Parfeny, the story of an Old Believer who went all over Russia before joining the Orthodox Church in Moldova. To Mount Athos, the Holy Places. We got a copy – Fr. Vladimir saw to it.