“It would be a species of torture to have any occupation in Palestine especially Jerusalem… Jerusalem prickles with adverse interests.” [1] Letter from Fr Nicholas to Fr Dimitrii (Balfour), 30.07.1936. Saint Nicholas Parish Archive, Oxford.

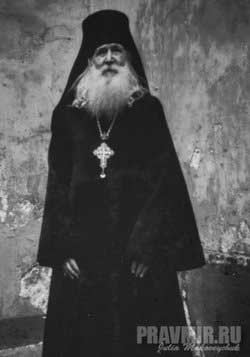

Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes).

Englishman Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes) (1876 – 1963) was a tutor to the children of the martyred Tsar Nicholas II. After the Russian Revolution and Civil War, he went to live in Harbin, Manchuria where, at the age of 58, in 1934 he converted to Orthodox Christianity in the Russian Church. There he became a priest. In 1936 Fr Nicholas left Harbin, where he had lived for more than 15 years. He travelled by ship, visiting en route Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Port Said in Egypt. From there he travelled to Jerusalem where he remained for some six months before returning to Port Said and sailing to England. This is the story of that journey, much of it told in his own words. [2] Fr Nicholas was an inveterate writer of lengthy letters, many of which are now held in the archive of the St Nicholas Russian Orthodox Parish, Oxford (SNPA – Saint Nicholas Parish Archive).

Departure from Harbin [3] Frances Welch, in her book The Romanovs and Mr Gibbes (London: Short Books, 2020), 111, omits completely the journey from Harbin and erroneously states that Fr Nicholas returned to England in 1937.

On 3rd March, 1936, [4] Lambeth Palace Library (LPL) DOUGLAS 47 ff32. Hegumen [5]Fr Nicholas had become an hegumen in 1935. In the Orthodox Church an hegumen is usually the head of a small monastery. However, hegumen is also a title of honour for certain monks who are priests, … Continue reading Nicholas (Gibbes) left Harbin, the city where he had lived for more than 15 years. Exactly why Fr Nicholas decided to leave is not clear but the political situation in Harbin was volatile and perhaps Fr Nicholas (no stranger to civil war and revolution) had a premonition of even darker days to come. Manchuria, of which Harbin was the principal city, had been taken by Japanese forces which invaded in 1931. The occupying forces imposed a brutal campaign of terror and intimidation against the local Chinese population as well as the tens of thousands of Russian exiles living in Harbin. [6]For an overview of the history of Russians in Harbin, see Mara Moustafine, “Russians from China: Migrations and Identity,” The International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, … Continue reading Also, Fr Nicholas had a somewhat ill-formed and vague idea to found a monastic community in England. Perhaps it was this that caused Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka [7]Metropolitan Nestor (Anisimov) of Kamchatka: In 1918 Bishop Nestor was the first Russian bishop to be arrested by the Bolsheviks but he escaped to Manchuria, becoming Bishop of Kamchatka and … Continue reading to tell Fr Nicholas to spend a year in the Russian Orthodox monasteries of the Holy Land en route for England.

Archbishop (later Metropolitan) Nestor (Anisimov) of Kamchatka.

“Fr Nicholas had the archbishop’s blessing as he set out for home, with special instructions to stop for a year at the Russian Orthodox Mission in Jerusalem in order to experience organized monastic life…” [8] Christine Benagh, An Englishman in the Court of the Tsar. (Chesterton, IN.: Ancient Faith Publishing, 2000), 260. Historian Petr V. Stegny makes a similar point, “Vladyka [Nestor], who tonsured him, stipulated that he was to spend a year in Russian churches in the Holy Land.” [9]Пётр Владимирович Стегний, Скитоначальник: жизнь и судьба игумена Серафима (Кузнецова) [Peter Vladimirovich Stegny, The … Continue reading

In 1936 the first week of the Great Lent commenced on Monday, 24th February. “… owing to the necessity of attending all our Lenten services (I had to go to confession at the end of the week) I absolutely could not manage it [say goodbye] as much as I desired to do so.” [10] SNPA 17.03.1936. For Fr Nicholas the last few days in Harbin were exhausting. “My last days in Harbin were a positive nightmare… during five days I only had one day of rest.” [11] SNPA 17.03.1936. This was because Fr Nicholas had an arduous round of meetings with friends and acquaintances in order to say “goodbye.” On the last day in Harbin Fr Nicholas attended the evening service at Dom Miloserdia (House of Mercy), after which there was a moleben (service of intercession) for Fr Nicholas’ health and safe journey back to England.

I think I never was so rushed in all my life. I had simply crowds of people to see and I had to go and have supper with my dear old friend Miss ffrench, for the last time. I sat with her until 3 a.m.… [Volodya] packed my boxes for me and we were not finished until between six and seven o’clock. And then at seven [a.m.] people began collecting again, talking until I, myself and my rooms were all in a whirl. Now I can hardly imagine it even! What a nightmare it has all been… [12] SNPA 14.03.1936.

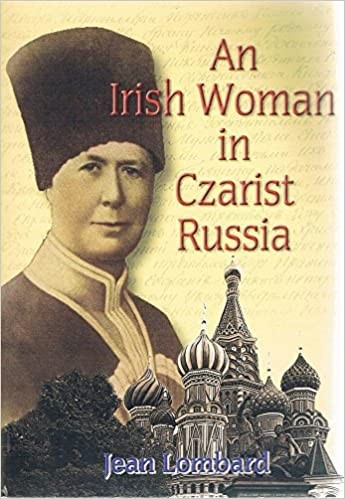

Photograph of Kathleen ffrench on the cover of her biography.

The “dear old friend” of Fr Nicholas was Kathleen ffrench, a wealthy British citizen and a devout Roman Catholic of aristocratic heritage. Like Fr Nicholas, Kathleen ffrench had survived the Russian Revolution, the Civil War and the horrors of the Soviet regime. Kathleen had arrived in Harbin in 1929 where she lived until her death in 1938, aged 73. [13] Jean Lombard, An Irish Woman in Czarist Russia (Dublin: Ashfield Press, 2010), 96.

Fr Nicholas began his journey of more than 10,000 miles with a 500-mile train journey from Harbin to the port of Dairen (now Dalian). Fr Nicholas was much concerned that the dozen or so suitcases and boxes which he was sending directly to England should receive the personal attention of the Japanese Chief of Customs, Mr Fukimoto. Fr Nicholas only had a few hours in Dairen before his ship was due to leave and he spent almost all the time trying to track down Mr Fukimoto. “He promised to give my luggage his personal attention and to make a note on the bill of lading if presented to him personally. He then took my photo on his cinematographic camera, for which purpose I can’t say.” [14] SNPA 11.03.1936. Fr Nicholas also managed to squeeze in a very brief visit to the British Consul General. Fr Nicholas made it to the ship with minutes to spare and could spend only a few moments in speaking with Bishop Juvenalis [15]Bishop Juvenalis (Kilin) was born in 1875. In 1921 he went to live Manchuria and in 1924 he founded the Monastery of the Kazan Icon in Harbin. In 1935 he was consecrated as Bishop of Xinjiang … Continue reading who, together with two priests, Fr Gabriel (“an intellectual looking priest”) [16] SNPA 12.03.1936. and Fr George who lived in Dairen, had come to see him off. “Bishop Juvenalis came down to see me off but my urgent correspondence prevented me from having more than a few words with him.” [17] SNPA 12.03.1936. One urgent letter he addressed to the baggage agency, the Oriental Express Co., instructing them to present the bill of lading to Mr Fukimoto. The other urgent letter was responding to a telegram from Archbishop Nestor, describing a series of incidents in Manchuria due to Fr Nicholas not having paid people before he left (including a cheque which was not honoured by the bank and somebody in Harbin (“the joiner”) being arrested as a result). [18] SNPA 12.03.1936. In a subsequent letter written on 12th March to Archbishop Nestor, Fr Nicholas expressed his irritation with the financial issues: “Please note that I do not accept responsibility for the account for candles for the King George Service, for which at the very last moment of my stay [sic] I received an account from the starosta [churchwarden]. At which I was more than annoyed.” [19] SNPA 12.03.1936. This stemmed from a moleben served some eight months previously by the Archbishop and Fr Nicholas in the Harbin Russian Orthodox Cathedral in May, 1935 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the accession to the British throne by King George V. [20] SNPA May, 1935.

In fact, Bishop Juvenalis had come down to the ship to say goodbye, not only to Fr Nicholas, but also to Fr Rostislav Gan who was married to a niece of the bishop. Having been ordained as a priest by Bishop Juvenalis only a few weeks previously, Fr Rostislav was sailing to Shanghai to become rector of the house chapel at the Commercial School in Shanghai, where he taught the Law of God and mathematics, in addition to teaching religion to Russian students of other international schools in Shanghai.

To Shanghai

Saint John (Maximovitch) in Shanghai, 1935.

And so, at the beginning of March, 1936, Fr Nicholas set sail from Dairen on an unnamed ship to Shanghai, where he arrived on Saturday, 7th March, 1936, and remained there until the following Tuesday. Like Harbin, Shanghai had become an important centre for Russian exiles. The “White” Russian population of Shanghai at that time was about 25,000 strong. The resident bishop of Shanghai was Bishop John (Maximovitch) (1896 – 1966) – later Saint John the Wonderworker of Shanghai and San Francisco.

Fr Nicholas planned to stay at the Burlington Hotel in Shanghai. However, instead he accepted hospitality for three nights in the house of a Shanghai port baggage handler. On Saturday evening he attended the All-Night Vigil at the newly built St Nicholas Cathedral.

Shanghai Cathedral under construction, 1936.

Fr Nicholas commented, “The new Church in Shanghai is a very handsome building, but generally speaking it is more attractive outside than in. It is very lofty and the evening I was there it was very cold as, except for one tiny stove; it is of course unheated.” [21] SNPA 13.03.1936. To Archbishop Nestor, Fr Nicholas wrote, “The Bishop stood for the Verchernaya [Vespers] on the ambon and I stood behind him. We then robed for the Gospel – which is read (as in the Anglican Church) to the west.” [22] SNPA 12.03.1936. To an English friend in Harbin, Fr Nicholas wrote, “… I went to call on the Bishop as soon as I got settled. Bishop John invited me to assist at the evening service, which was very long, finishing after 10. We then had some conversation and I partook of their evening meal.” [23] SNPA 12.03.1936. On Sunday Fr Nicholas joined Bishop John at another church in Shanghai, located on Wayside Road (now Huoshan Road) where the rector, Fr Sergey Borodin, was awarded the gold cross to mark the 25th anniversary of his ordination. [24]Archpriest Sergey Borodin: born circa 1879. Ordained priest, 1911. During WW1 he was a military chaplain. In 1922, Fr Sergey left Vladivostok and went into exile in Shanghai. After 1948, he moved to … Continue reading Fr Nicholas recalls, “The father was a nice, pleasant, kindly man and it was a real pleasure to assist at his triumph. There were quite a lot of persons at the “cup of tea” which followed and of course I was an item of interest. For most people knew of me and few had ever seen me.” [25] SNPA 12.03.1936. On Monday there was a lunch party for Fr Nicholas, hastily arranged by his former Harbin colleague, Mr P. G. S. Barentzen, now Shanghai Commissioner of Customs. At the lunch were several former colleagues from the Maritime Customs Service of China who had transferred from Harbin to Shanghai.

Hong Kong and Singapore

Schedule of voyages, NYK Shipping line.

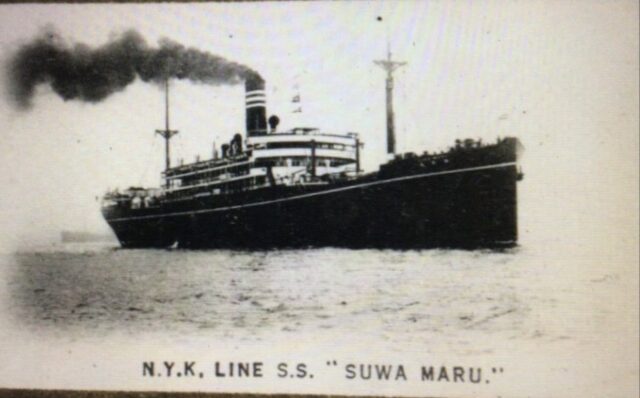

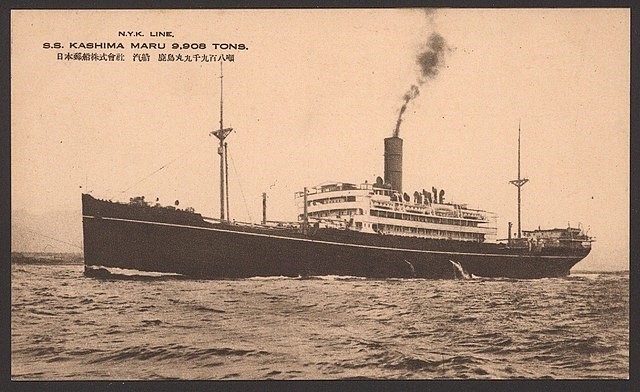

On Tuesday 10th March, 1936, Fr Nicholas set sail, not before arranging to send the balance of his Japanese currency to Archbishop Nestor through the Orient Express baggage agency. Fr Nicholas was on the s.s. Suwa Maru, a Japanese ocean liner owned by Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK). Commented Fr Nicholas, “The ship ‘Suwa’ is old and not too comfortable, but it might be worse and I do not anticipate a bad voyage.” [26] SNPA 11.03.1936.

Arrival in Hong Kong was delayed by heavy fog and, as result, his time ashore was much briefer than had been scheduled. “We are standing outside the harbour of Hong Kong as I write, fogbound. The fog (to me) doesn’t seem so bad but evidently the captain is afraid of the rocks and we haven’t moved for the last four hours…” [27] SNPA 15.03.1936. Fr Nicholas did have time to visit “the new Russian church, a very nice place on the Kowloon side: I was told that there are now 200 Russians living there. The batushka [Priest Dmitri Uspenskii, d.1969] was unfortunately away, being expected back from Manila the next day only.” [28] SNPA 17.03.1936. The church which Fr Nicholas visited in fact was the Anglican church of Saint Andrew in Nathan Road which at that time offered hospitality to the Russian Orthodox community. [29]Archpriest Dionysy Pozdnyaev, The Russian Church Abroad in Hong Kong. Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad. 8.1.2019. Accessed February 2021. … Continue reading Fr Nicholas rejoined his ship which departed from Hong Kong on the same day, 15th March. Three days later the s.s. Suwa Maru reached Singapore and Fr Nicholas was able to get off the ship. In his correspondence from the ship, Fr Nicholas fails to mention that one of his fellow passengers between Shanghai and Singapore was global star Charlie Chaplin and his entourage; they received a tumultuous welcome on the Singapore quayside as they disembarked. [30] Raphaël Miller, “Chaplin in Singapore,” biblioasia, vol. 13, Issue 1 (April-June, 2017): 2-9.

s.s. Suwa Maru.

In Singapore, by happy chance Fr Nicholas was able to meet up briefly with Bishop Dmitri [31]Archbishop Dmitri (Voznesenky): Emigrated to Manchuria and served at various churches in Harbin until 1931. Upon the death of his wife in 1933, tonsured a monk. In 1934 was consecrated as Bishop of … Continue reading who had been attending the 1935 meeting of the Council of Bishops in Serbia.

Bishop Dmitri (Voznesensky) of Hailar,

the father of the future Metropolitan Philaret.

On his way back to Manchuria, on the instruction of the Council of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), Bishop Dmitri visited first Colombo, the capital of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and then south India. [32]Nicolas Mabin, Russian Exiles and the Indian Orthodox Church (1931 -1939). Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad. February, 2019. Accessed December, 2020. … Continue reading Writing to his godmother, Elizabeth Nicolaevna, Fr Nicholas reported,

… I had the pleasure of meeting Bishop Dmitri (Hailar), who was returning home. … I was therefore glad to hear from his own lips an account of his mission to the Travancore Indian Christians who are known (I believe) as the Syrian Christians. The result was perhaps a little disappointing, as actually no definite agreement was reached. The preliminary work previous to the Bishop’s visit became itself of that nature. The Bishop was greatly hampered by having no knowledge of any language except Russian, which was only understood by one priest, who translated it into English. Then another Indian priest translated the English into their own language. Not an ideal arrangement. [33] SNPA 31.03.1936.

Departing on the next day, 19th March, from Singapore the s.s. Suwa Maru sailed to Penang in Malaysia, Colombo in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Port Aden in the Yemen, and up through the Suez Canal before dropping anchor at Port Said in Egypt where Fr Nicholas disembarked on Monday, 6th April, 1936. Looking back, Fr Nicholas remarked, “We never had one rough day on our voyage here!” [34] SNPA 20.07.1936.

To Jerusalem

From Port Said Fr Nicholas took another ship, this time of the Khedivial Mail Line, which sailed to Jaffa and then on to Haifa with its final destination at Alexandretta (now İskenderun) on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey. At that time Jaffa did not have a harbour big enough to accommodate a large ship and so, after one night’s voyage, Fr Nicholas had to take a smaller launch from the steam ship to the port. “Jaffa has no harbour and the landing of any small boat is unpleasant especially when you have many small pieces of luggage. However, there were no accidents and I got to shore about 8 a.m.” [35] SNPA 30.07.1936. Despite the arduous journey ahead of him, Fr Nicholas did not travel lightly. His luggage included two suitcases, two hand bags, a hat case, a holdall with rugs, a typewriter, his staff, and a Japanese coffee service which a Father German in Harbin was sending via Fr Nicholas to an acquaintance in Belgrade. [36] SNPA 24.04.1936. From the port Fr Nicholas went to the Russian Convent of Apostle St. Peter and the Tomb of St Tabitha in Jaffa. The small community of nuns was led by Abbess Evgeniia (Mitrofanova, d. 1959), the mother of one of his former pupils in St Petersburg, some twenty years previously. [37]Abbess Evgenia (Mitrofanova) founded a monastic community in France which lasted from 1926 to 1934. She became the Abbess in 1930. After the partition of Israel in 1948, Abbess Evgenia lived with a … Continue reading Fr Nicholas was invited to stay the night at the convent. On the following day he joined the Abbess and some of the nuns as they travelled by bus from Jaffa to Jerusalem for Pascha. Fr Nicholas finally arrived in the Holy City on Great and Holy Wednesday, just a few days before Pascha which in 1936 fell on 12th April (civil calendar).

The Arab General Strike

In order to appreciate the context of the visit of Fr Nicholas to the Holy Land, it is necessary to understand the impact of the Arab General Strike. This lasted from April until October, 1936, frustrating many of the plans of Fr Nicholas and greatly impacting his departure date.

Archbishop (later Metropolitan)

Anastassy (Gribanovsky).

For example, when he accompanied Metropolitan Anastassy [38] Metropolitan Anastasy (Gribanovskii) (1873 – 1964): First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia from 1936 to 1964. on his Paschal visitation to the Russian Orthodox communities of Palestine, Fr Nicholas recorded that after their visits to the monasteries and churches in the area of Jerusalem, “we were to go to the Sea of Galilee and the day before we were to start the strike commenced and since then, except for one visit to Jaffa, I have never been anywhere. We are all waiting to begin and we have all waited so long that I am now practically the only pilgrim left.” [39] SNPA 20.07.1936. In the same letter, written nearly three months after his arrival in Jerusalem, Fr Nicholas commented, “The strike began soon after my arrival that I hardly know Palestine under any other condition and it has now gone on for such a long time that one has begun to get accustomed to strike conditions and they now almost seem normal.” [40] SNPA 20.07.1936. Elsewhere, Fr Nicholas describes the Arab Strike as a ‘rebellion’. “‘Rebellion’ is far nearer the truth than ‘strike’, though it certainly differs from the rebellions of modern times for it is conducted with more than a little chivalry on either side. Chivalry, which is now becoming more and more despised and discarded all over the world, here still holds sway.” [41] SNPA 04.09.1936.

Jaffa, 1936. British troops searching local inhabitants for arms.

Fr Nicholas knew that the Arabs had no quarrel with the Russian exiles in Palestine “with whom on the contrary they are very friendly as ‘brothers in distress’ and of course I pass as Moskva without any question on account of my clothes.” [42] SNPA 12.06.1936. The uprising was a protest against the British administration of Palestine and against the concept of a “Jewish National Home”. Writing in August, 1936, to his sister, Winifred, Fr Nicholas said that even on the Mount of Olives they hear “shooting every day and every night.” [43] SNPA 13.08.1936. Martial law was in place, including a curfew from sunset to sunrise. He said that “one of the [British] military chaplains was here last week and he promised to take me to Bethlehem and if he doesn’t, I shall walk there one day and come back the next. However, Jordan and St. Savva’s they say are too dangerous to attempt.” In September, Fr Nicholas observed,

So, I don’t feel the least tremor at going through the Arab city for there is nothing but smiles and friendly greetings…. They want first and foremost – Jews, and then their protectors, the British soldiers and police. That is the situation in a nutshell. The only unsafe locomotion is therefore in motor cars and by trains. These are the objective for it is a good way of reaching the Jews and the soldiers. The motor cars and buses are generally speaking attacked singly but not in convoys by either rifle fire or bombs. The trains also in a similar way. From Arab sources I have learned today that today is the “last day” of Arab moderation if they don’t get some guarantee from the Government. That sounds like blowing up more trains! [44] SNPA 18.09.1936.

Pascha, 1936

Fr Nicholas arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of Holy Week and went straight to the Russian Mission. On his first full day in Jerusalem, after the Divine Liturgy of Great and Holy Thursday at the Russian Cathedral, Archbishop Theophan, [45] Archbishop Theophan (Gavrilov) (1872 – 1943); at this time, he lived in Belgrade where he was the head of the Chancellery of the ROCOR. Archimandrite Varnava (a pilgrim from Serbia), [46]Archimandrite Varnava (Šaškov) was hegumen of the Sukovo monastery in the late 1930’s. Date of birth unknown. In 1943 Fr Varnava was killed by Bulgarian fascists. I am grateful to Srećko … Continue reading Fr Philip (Gardner) [47]Born Ivan Alexeyevich Gardner (Иван Алексеевич Гарднер) in the Crimea in 1898, he emigrated to Belgrade in 1920. In 1931 he was ordained as a monastic priest for the ROCOR and … Continue reading and Fr Nicholas hurried from the Russian Mission to the Holy Sepulchre but were just too late to see the ceremony of the Washing of the Feet, held in a square outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Pilgrims gather there to witness the ceremony which is in honour of Christ’s washing the feet of His disciples. Taking place at the end of Divine Liturgy, the service in Jerusalem is usually performed by the Patriarch who washes the feet of twelve priests. However, they were in time to hear a sermon being preached in English, “very correct but, as one might well expect, rather stilted and academic.” [48] SNPA 04.09.1936. The Greek Orthodox Patriarch Timotheus I (d.1955) did not perform the ceremony nor any other ceremony during that Pascha owing to the growing unrest. It was said that his life was threatened if he appeared at any ceremony.

Washing of the Feet, Holy Sepulchre, 1936 © alamy.com

On the evening of Great and Holy Thursday Fr Nicholas joined all the clergy of the Russian Mission, led by Metropolitan Anastassy, in praying at the Russian convent Church of St Mary Magdalene in the Garden of Gethsemane. All the clergy, sisters and the congregation then made their way from Gethsemane along the Via Dolorosa to the Holy Sepulchre. As they approached the Holy Sepulchre, they first visited the Church of St Alexander Nevsky at the Russian Excavations (Alexandrovskoe Podvor’e) and venerated the gate threshold, believed to belong to the Judgement Gate, by which Jesus left the city on the way to the hill of Calvary. On the next morning, Great and Holy Friday, Fr Nicholas attended services at the Russian Cathedral. In the evening he went to the Holy Sepulchre for the Service of Lamentation. Fr Nicholas noted that the extremely long service was attended by a large number of foreign residents of Jerusalem, including the High Commissioner, Sir Arthur Grenfell Wauchope, and three Anglican bishops.

In a lengthy letter addressed to Miss ffrench in Harbin, Fr Nicholas described how he returned on Great and Holy Saturday to the Holy Sepulchre for the Holy Fire. [49] SNPA 20.07.1936. “Such scenes of enthusiasm I have never witnessed in a Christian church. It seemed a miracle to me that the church was not burned down by the sacred fire for eventually there were hundreds of people all holding bunches (mostly containing 33 candles) of burning candles.”

At the Russian Mission

Writing to Count Yuri P. Grabbe [50] Count Yuri P. Grabbe (1902 – 1995). Later Bishop Gregory (Grabbe) of Washington and Florida. in Serbia, Fr Nicholas said that he had been,

…most kindly received by His Grace, the Metropolitan Anastasy and the Reverend Archimandrite Anthony. [51] Archimandrite Anthony (Sinkevitch) (1903 -1966). Head of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, 1933 – 1951. Later Archbishop of Los Angeles. I am stopping in the Mission House and am slowly absorbing the glamour and the charm of the Holy City. The Metropolitan most kindly took me with him on his Easter visits to most of the Convents and Establishments that he is accustomed to visit at this season of the year. [52] SNPA 28.04.1936.

Those visits with the Metropolitan included two convents – one on them being the Mount of Olives Convent of the Ascension and the other at Ain Karem, the birthplace of Saint John the Baptist. They also visited Hebron “where the great oak stands under which Abraham entertained three angels. The Russians have a big church there and a nice hostel, where we stayed the night.” [53] SNPA 20.07.1936.

During April and May Fr Nicholas lodged at the Russian Mission, “an enormous place” [54] SNPA 20.07.1936. with about ten extensive buildings and the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity at the centre where Fr Nicholas attended morning and evening services on most days while he was resident in the Russian Compound. By that time most of the buildings had been let to the Palestine government because they were no longer required for the pilgrims for which they were built. Some the buildings were being used for the Law Courts, as well as a hospital and a mortuary. Fr Nicholas lived opposite the mortuary and the daily arrivals of bodies of Arabs caught up in the civil unrest demonstrated to Fr Nicholas the seriousness of the conflict. Fr Nicholas noted that of the central block (formerly used only by the clergy), half then housed everything except some nuns who lived in two other buildings. “The property is controlled in part by the Ecclesiastical Mission and in part by the Palestinian Society, [55]When it was founded, the organisation was known as the “Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society.” In 1918, following the Russian Revolution, it was re-named as the “Russian Palestine Society.” … Continue reading and the two bodies are of course at logger heads.” [56] SNPA 20.07.1936. Fr Nicholas thought his room to be perfectly nice, “very plainly furnished and, of course, entirely lacking in service.” There was a refectory and a “common dinner at 12 noon which is shared by the Metropolitan but breakfast and supper he takes in private.” [57] SNPA 20.07.1936. Writing to Archbishop Nestor, Fr Nicholas said that his “only sufferance has been the fish diet [sic] in the trapeza [refectory], but even to that one got accustomed and my dear new colleague, Father Lazarus Moore, [58] Regarding Fr Lazarus, see later section, “Hieromonk Lazarus (Moore).” showed me how it was possible to supplement the trapeza much in the same way as we used lavka [shop] in Dom Miloserdia.” [59] SNPA 04.09.1936.

At the Russian Mission Fr Nicholas became good friends with an Archimandrite Varnava, who was visiting from the monastery at Sukovo, south east Serbia, which had many Russian connections. Fr Nicholas also befriended Hierodeacon Seraphim (Sedov) (1896-1984) who “was also a link with former times and we have become fast friends.” Fr Nicholas was at pains to note that everybody, from the Metropolitan “down to the least member of staff”, had shown him exceptional kindness.

Commenting on the services in the Russian Cathedral, Fr Nicholas said that they “were very beautiful and were not lacking in anything that could render them unworthy of the great foundation but the choir is naturally not as fine as that of Harbin.” [60] SNPA 20.07.1936. Writing to Archbishop Nestor, Fr Nicholas expressed his wonder:

The fine cathedral and its magnificent iconostasis and a “Riznitza” that seems just like a dream. It seems to me that they could change the vestments every week and never use the same ones more than once in a year! But this is not only the case with vestments but of everything also besides. Copies of the Holy Gospels, one heavier and more beautiful than another; magnificent communion plate and Holy Tabernacles, candlesticks, censers, and everything else that one can imagine. The Easter services were celebrated with all the magnificence and stately pomp of ancient times, one Metropolitan, one archbishop, four archimandrites, two abbots, and six or eight lesser clergy. [61] SNPA 04.09.1936.

However, he observed that there were few subdeacons and altar servers because there were so few Russian Orthodox families living in Palestine. Most of the congregation comprised stranded pilgrims, mostly women, who had been in Jerusalem since (or even before) the start of the First World War. Additionally, there were a few refugees, recently arrived from the south of Russia, as well as some deserters from the Red Army who had made their way over the border to Persia and thence to Palestine, where the British authorities treated them with relative leniency.

At the beginning of June Fr Nicholas wrote that “my Palestine visa expires in about a month’s time but I understand that it can easily be renewed for a further period. The question is, is it worthwhile?” As it turned out, the fraught political situation prevented the departure of Fr Nicholas from Palestine for another three months.

Abbess Mary (Robinson)

Abbess Mary (Robinson).

It is worth pausing here to recall the life of Abbess Mary (Robinson) [62]“The Bethany Community of the Resurrection of the Lord,” Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem. n.d. https://www.jerusalem-mission.org/bethany Accessed February 2021. Maria Kozlova, … Continue reading who, with the blessing of Metropolitan Anastassy, invited Fr Nicholas to leave the Russian Mission and take up residence in the Garden of Gethsemane. Born in Glasgow in 1896, the then Marion Robinson, after completing nursing and medical studies, became a novice of an Anglican community of nuns. She was given the name Stella and was sent to India for missionary work. In 1932 Stella, having made a visit to London, was returning to India and decided to visit Jerusalem en route, together with another sister, Alix Sprott. In Jerusalem the sisters rented a cottage in the Garden of Gethsemane which was owned by the Russian Palestine Society. Inspired by the life and martyrdom of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, [63] Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia (1864 – 1918): see the next section. whose remains are interred in the Gethsemane church, in 1933 they decided to become Orthodox nuns under the guidance and care of Metropolitan Anastassy. A year later they were tonsured as nuns in the church of St Mary Magdalene, Garden of Gethsemane by Metropolitan Anastassy: Stella became Mary and Alix became Martha. At this time in the Garden of Gethsemane there was no convent – simply the magnificent church and a few very modest cottages. Initially, the Russian Orthodox community of nuns was founded in Bethany, some two miles from Jerusalem, where the Lord raised Lazarus from the dead. The official name of the community is still the ‘Bethany and Gethsemane Community.’ Later on, Mother Mary was put in charge of the Gethsemane property and Mother Martha was appointed as her assistant with responsibility for the Bethany community and school. In October, 1936 Mother Mary became the Abbess. Both Gethsemane and Bethany flourished under the loving care and devotion of Abbess Mary and Mother Martha. Abbess Mary died in 1969 and Mother Martha (subsequently Abbess Martha) died in 1972. The church of St Mary Magdalene in the Garden of Gethsemane is especially revered because it is also the resting place of the remains of the New Martyrs, Elizabeth and Nun Barbara.

The New Martyr Elizabeth, Grand Duchess and Abbess

Born in 1864, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth [64]See Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovskii), “Life of the Holy New Martyr Grand Duchess Elizabeth,” Orthodox Life vol. 31, no. 5 (Sept.-Oct., 1981): 3-14. Also, Life of the Holy New Martyr Grand … Continue reading married in 1884 Grand Duke Sergei, son of Emperor Alexander II. In 1905 Grand Duke Sergei was killed by a terrorist bomb. The widowed Grand Duchess established a charitable community in Moscow which in 1909 became the Convent of Mercy of St Martha and St Mary, dedicated to helping the downtrodden of Moscow.

Grand Duchess and Holy Martyr Elizabeth.

In 1910 she was made Abbess of the Convent, which then housed 45 sisters. After the Civil War and Revolution, in 1918 Abbess Elizabeth was ordered to leave Moscow and go to Perm in the Urals. From there she was moved to Alapayevsk where Abbess Elizabeth lived in captivity. On 18 July, 1918, Abbess Elizabeth, Sister Barbara, and five other members of the Imperial Family were martyred, first being blindfolded, and then thrown alive into a mine shaft. In September, 1918 the White Army liberated Alapayevsk, found the mine and removed the bodies. In 1919, the White Army took the coffins with the bodies, first to Siberia and then in 1920 to China. The other five members of the Imperial Family were buried but the coffins of Abbess Elizabeth and Sister Barbara were placed in the crypt of St Seraphim’s church in Peking (Beijing). From there they were removed to Palestine, with support from Abbess Elizabeth’s older sister, Victoria, Marquess of Milford Haven (d. 1950). Archpriest Andrew Phillips wrote of this event,

On 28 January, 1921, the relics were solemnly met in Jerusalem by Patriarch Damian, Russian and Greek clergy, members of the British authorities and innumerable Orthodox faithful. Here Abbess Elizabeth was buried in the church of St Mary Magdalene in Gethsemane. In 1888, before ever becoming Orthodox, the Grand Duchess had already expressed the desire to be buried here. This had been at the consecration of that very church, where she had gone with her husband, who was President of the Russian Palestine Society. Abbess Elizabeth was canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in 1981, and in 1992 by the Moscow Patriarchate. [65] Archpriest Andrew Phillips, “The Holy New Martyr Grand Duchess Elizabeth (+1918),” Orthodox England, (December 2002). http://orthodoxengland.org.uk/elizabet.htm Accessed March, 2021.

The man largely responsible for the heroic feat of bringing the coffins of the holy martyrs from Peking to Jerusalem was Abbot Seraphim (Kuznetsov). We shall learn more of Fr Seraphim and his interaction with Fr Nicholas later in the story.

It will be remembered that it was Archbishop Nestor of Kamchatka who had encouraged Fr Nicholas to visit the Holy Land on his way back to England. The Archbishop himself had made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the previous year, 1935, and a year later, he published The Holy Land (Syria and Palestine). The Archbishop had a great devotion to the martyred Grand Duchess Elizabeth whose remains are interred in Jerusalem. Indeed, he believed that the Saint had appeared to him twice, once in the Pokrov Convent in Chita, Siberia, and again during his 1935 pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Of the second appearance, Archbishop Nestor wrote,

On the Feast of the Holy Protomartyr Stephen, when we were serving the Divine Liturgy in the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene, I saw a marvellous vision: I saw the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna walking along the solea [narrow walkway] by the iconostasis and praying at the local icons, and then walking up to the icon of the Archangel Michael. She prayed there and disappeared in a light fog. This vision filled my soul with fear and reverence, and that same moment I confessed it to Archbishop Anastasy, who was praying in the altar.

The memory of the Grand Duchess and her righteous, pious, God-pleasing life is alive in Gethsemane; her spirit lingers above this holy place; and now her image has inspired several Russian and English Orthodox nuns to begin the same work to which the Grand Duchess’ life had once been devoted: that of mercy in the name of Christ. [66]Aрхиепископ Нестор Анисимов, Святая Земля (Сирия и Палестина) (Archbishop Nestor Anisimov, The Holy Land [Syria and Palestine]). (Harbin, 1936). … Continue reading

In the Garden of Gethsemane

In the first week of June, 1936, Fr Nicholas moved from the Russian Mission to the Mount of Olives where he inhabited a two-room cottage, the priest’s house, in the grounds of the church of St Mary Magdalene. The church in the Garden of Gethsemane was built by Alexander III. Its trustees were the Russian Palestine Society [67] see footnote 55 above. of which the husband of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, the Grand Duke Sergey Alexandrovich, was founder and first president. Fr Nicholas noted that

The church… is in general very small… The church is beautiful, everything Tsarsky, the Image behind the altar is the work of Vereschagine, that over the Table of Oblation (Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane) by Ivanov – the Academician I think, though at the present time most of the vestments and practically all the plate has been removed to the cathedral for safety. [68] SNPA 20.07.1936.

In his lengthy description of the Gethsemane church Fr Nicholas makes no mention of the crypt within which rest the remains of the Holy New Martyrs Elizabeth and Barbara.

Writing again on 6th June to his adopted son in England, George Paveliev Gibbes, Fr Nicholas reports that he was suffering from a hernia which had first become apparent when on the ship. He had consulted three doctors in Jerusalem, all of whom said that he was too old for an operation and that the best remedy was to wear a bandage “which is a great nuisance”. [69] SNPA 06.06.1936. On that particular day Fr Nicholas wanted to go to the Russian Mission to use a Russian typewriter. “If I start now, I shall have to have lunch there and I don’t want to do that for it is invariably FISH [sic], so I had better wait here till twelve o’clock and have lunch here and go in later…” He again mentions the deteriorating political situation, noting that in Jerusalem he felt relatively safe because of the “swarms of soldiers and police”, [70] SNPA 06.06.1936. saying that there is now a night curfew from 7 pm onwards and that his hope of seeing Palestine beyond Jerusalem was fast diminishing. By now he is certain that he does not want to remain in Jerusalem for long; it seemed to Fr Nicholas that in the Middle East there was just as much political unrest as there was in the Far East.

A week after moving to Gethsemane, it was arranged that he should move from the priest’s house to a small house that stood at the very top of the Garden, high upon the Mount of Olives and was accessed by a steep incline which Fr Nicholas found quite arduous. Although the new place was bigger and had a toilet attached, Fr Nicholas said that he did not like it as much as the priest’s house. The new house was rented from the Russian Palestine Society by an English lady, Miss Alexander, who had gone to England for six months. Of course, it was filled with her possessions which were not to the taste of Fr Nicholas. Off the sitting room was another room:

It is very small and rather dark and contains a small cupboard full of books, … a small [rug] on the floor and an altar! The lady is high church and has her own chapel and, in a corner, there is a bit curtained off behind which hang priests’ vestments, so she has had even a celebration of Holy Communion here. [71] SNPA 12.06.1936.

However, to Archbishop Nestor he wrote in a more positive tone, “I have therefore been in luxury, having the whole use of three small rooms and also a terrace, where I generally take my meals, except when I go down to the trapeza, which does not happen very often.” [72] SNPA 04.09.1936. Fr Nicholas by no means served Divine Liturgy every day. He did take some of the services at Gethsemane but few sisters were living there and services were irregular. Indeed, up until 1935 there was only one service a week – on a Saturday, when Archbishop Anastassy served Divine Liturgy. Fr Nicholas noted that on 5th June he had served Divine Liturgy in the Gethsemane church, “the first time since I left Harbin, in fact since before Lent.” [73] SNPA 12.06.1936. He expressed relief at not having to eat at the Mission but at the Convent, suggesting that the food at the Mission must be “very trying”.

As time progressed, the relationship between Mother Mary and Fr Nicholas became quite fraught. For example, there had been some confusion as to which priest should serve the All-Night Vigil and Divine Liturgy for the feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist (24 June/7 July) at the church in the Garden of Gethsemane, since there had not been a resident priest there for more than ten years. Fr Nicholas thought it was to be him. As it turned out, Mother Mary had invited Fr Philip (Gardner) from the Russian Mission to serve and had failed to notify Fr Nicholas who was less than pleased at this apparent sleight. In her defence, Mother Mary said that she thought that serving without a deacon would be too much of a strain for Fr Nicholas and, anyway, she thought that at the last moment he “might be wanted to go to Ain Karim which was a much greater joy for you.” She humbly asked for his forgiveness. [74] SNPA 09.07.1936.

Between 31st July and 12th August Fr Nicholas composed a 3,000-word letter to Fr Dimitrii (Balfour) in Athens. [75] Regarding Fr Dimitrii, see later section ‘Future Plans’. Fr Nicholas began by announcing that he had decided not to travel to Greece. The original plan was to go by ship to Greece to meet Fr Dimitrii in Athens and then go to Mount Athos in order to buy Slavonic liturgical books. After that, he would travel to Serbia to meet Metropolitan Anthony [76] Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitskii) (1863 – 1936). First Hierarch of the ROCOR from 1919 to 1936. and request a “gramata” from the Synod (letter of commendation) in connection with his work in England. Fr Nicholas says that, apart from the additional expense of making the journey, he was feeling the burden of the Middle Eastern heat. However, if he delayed his Greek trip until the autumn, that would delay unduly his arrival in England, where he was “anxious to arrive before the cold actually sets in.” [77] SNPA 30.07.1936. He went on to say that he now plans to leave Palestine after the feast of the Dormition (15/28 August). He would join an NYK steamer ship in Port Said, Egypt, since he already held a through ticket from Shanghai to London, and he expected to arrive in England on 22nd September, 1936.

Fr Nicholas confided in Fr Dimitrii that he “begins to long for home.” [78] SNPA 31.07. 1936. Apart from the summer heat, he finds what he calls “intrigue” was making life in Jerusalem very distressing. He continues, “For this very reason I should think it would be a species of torture to have any occupation in Palestine especially Jerusalem… Jerusalem prickles with adverse interests.” He was pondering which route he should take in returning to London. As we have seen, Fr Nicholas wanted to visit Greece and Serbia on the way but was undecided exactly what to do. As it turned out, Fr Nicholas failed to make the proposed visit to Greece and Serbia. In August, he wrote that “The sad demise of the old Metropolitan has, more than ever, made a journey to Serbia at this juncture quite useless.” [79]SNPA 31.07.1936. Fr Nicholas began to compose this letter on 31st July but did not complete it until after 10th August, the date of the repose of Metropolitan Anthony. Fr Nicholas often composed his … Continue reading

On the next day, 13th August, Fr Nicholas went to the Russian Mission to co-serve a panikhida (memorial service) for the newly-departed Metropolitan Anthony. Later that day he wrote a letter to his sister, Winifred, in Birmingham, with good wishes for her upcoming birthday in October. In conclusion, Fr Nicholas told his sister,

I have been here so long that people begin to ask me whether I am here permanently! I like Palestine very much (who doesn’t?) but I hardly think that I would live here except under certain conditions which I fear I shall never be offered!… I feel very much that I require a real rest at home and am looking forward to the peace and quiet of home life. [80] SNPA 13.08.1936.

The Arab Strike made a further impact on life in Jerusalem when the Government Authorities banned the procession which normally takes place at the nearby Tomb of the Virgin on the Dormition Feast (15/28 August). From Bethany, Fr Lazarus wrote to Father Nicholas, “That means that we shall not be at the Church in Gethsemane for the Feast, for there will be absolutely nothing to see. Everywhere there will be merely quiet services, and the Greek Liturgy will be an ordinary one, such as one can see anywhere.” [81] SNPA 12.08.1936.

Tensions existing between Fr Nicholas and the Mothers Mary and Martha developed into a full-scale hostility by the time Dormition feast arrived. In another letter to Fr Dimitrii in Athens, Fr Nicholas warned him,

I have had more than slight differences with Mother Mary and her shadow [sic]. You can make no estimate of either from a few hours conversation for they are exceedingly fair-spoken persons. As they were formerly very insistent on my returning here as their domestic chaplain, I felt it necessary to put them to the test before risking my own peace of mind in such a manner. I won’t say any more than that the proposition is now mutually extremely repugnant to both parties. [82] SNPA 01.09.1936.

During the course of September, the relationship between Fr Nicholas and Mother Mary went from bad to worse. At the request of Mother Mary, the Head of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem wrote to Fr Nicholas, politely asking him to vacate the house in the Garden of Gethsemane. “Owing to the influx of new sisters, our community which is currently located in Gethsemane is currently experiencing a severe shortage of space, leading to many difficulties for the resident nuns.” [83] SNPA 19.09.1936. (Translated from the Russian.) He asked Fr Nicholas to relocate to the Mission. Fr Nicholas responded by pointing out that the property belonged to the Russian Palestine Society, not the Mission; by implication this matter was not the business of Fr Anthony. It will be recalled that Fr Nicholas moved into the small house at the summit of the Garden of Gethsemane at the request of Mother Mary, not Miss Alexander. However, Fr Nicholas asserted somewhat disingenuously that he was there by invitation of the “tenant-in-chief”, Miss Alexander, who “is entitled to invite whomsoever she will into her own house and that whoever enters her house can hardly be removed (however politely it may be expressed) without her knowledge and consent.” [84] SNPA 20.09.1936.

Astonishingly, within a month, Fr Nicholas accused Mother Mary and her sisters of theft. A priest’s prayerbook had been sent to him from the Russian Mission. Having been delivered to the Convent, it then disappeared. Despite repeated enquiries by Fr Nicholas, the prayerbook remained unfound. Fr Nicholas wrote to Mother Mary in the most disparaging terms:

I am told that a thorough search has been made for the book but that it cannot be found. If this is the case, there is only one conclusion that can be drawn, and that is that the book has been stolen… Yet nothing whatever is done about it. I regret to say that I see you acquiesce in the fact of the theft. You mistakenly judge that, not having participated in the theft yourself, you are therefore innocent. But that is not so. This is an obitel [monastery] and the guilt of one is shared by all and therefore, until the book is found, you are all guilty of theft, for you belong to an obitel where theft has been committed. And such a theft – it wasn’t money, or food, or clothing but a holy book, and it is treated with no more consideration than if it was the loss of a novel or a box of sweets. The responsibility for this unhappy occurrence undoubtedly falls chiefly on you, Mother Mary, as the head of this Holy Obitel. If the obitel were better directed it could not have happened as it has. A theft of a priest’s prayer book in a Holy Obitel – and nothing done and very little said. Your moral senses have got blunt. [85] SNPA 11.10.1936.

Of course, it is impossible to know the rights and wrongs of the situation but the immoderate language of Fr Nicholas must have been deeply upsetting for Mother Mary – not least, because only two days previously she had been elevated to become Abbess and the joy of such a memorable occasion must have been marred by this allegation.

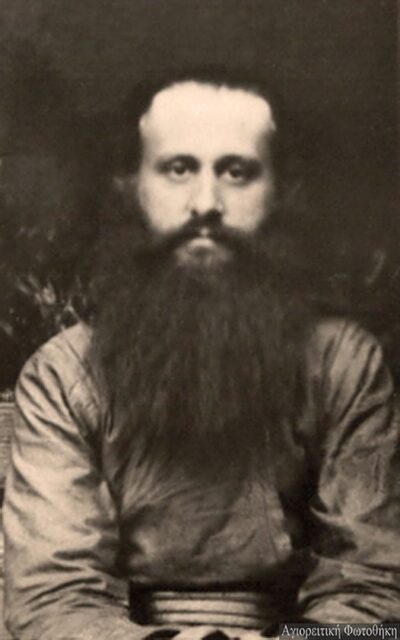

Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov)

Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov).

Another close acquaintance of Fr Nicholas in Jerusalem was Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov). Born in 1875 in Cherdyn, Perm, Fr Seraphim was ordained as a hieromonk in 1905, becoming an hegumen in 1912. Through his published essays, Fr Seraphim became a famous advocate of the Romanov dynasty and this brought him into contact from time to time with the Russian Royal family. Indeed, the famous historian, S. Fomin, records that in their last meeting in the spring of 1917, Abbess Elizabeth (the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna) said to Fr Seraphim “If I am killed, I ask you to bury me in a Christian way.” [86] S. Fomin, “Серафим (Кузнецов) [Seraphim (Kuznetsov)],” XPOHOC. http://www.hrono.ru/biograf/bio_s/serafim_kuznec.html Accessed March, 2021. Translated from Russian.

In 1919, as the White Army withdrew from Perm, Fr Seraphim and two novices from the Seraphimo-Alexeyevsky Skete, Perm, accompanied the coffins of the Alapayevsk martyrs, first to Siberia and then to Peking in 1920. With the support of the older sister of the martyred abbess, the Marchioness of Milford Haven, Fr Seraphim heroically ensured that the remains of the Abbess and Sister Barbara were safely transported by ship from Shanghai to Port Said and then on to Jerusalem.

Soon after arriving in Jerusalem, Fr Seraphim began to experience difficulties in his relationships, both with the clerics of the Russian Mission and also with the administrators of the Russian Palestine Society. There were two main elements contributing to his difficulties. Firstly, by nature he was outspoken and fearlessly vocal in his criticism of people of whom he disapproved. Second, Fr Seraphim lacked a natural affinity with the bishops of the Synod of the ROCOR; he believed that he should remain loyal to Patriarch Tikhon and his successors in the Soviet Union and that to become a priest of the ROCOR would betray that loyalty. As an extreme example of both traits, Fr Seraphim, in a widely circulated memorandum, once described Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitskii) as “the Antichrist.” [87] Stegny (2017). 193. Translated from Russian. In 1923, days before he was deprived of the right to serve as a priest by the ROCOR Synod, he petitioned Patriarch Damian I (d. 1931) for sanctuary. It suited the Greek Patriarch to accept Fr Seraphim into his jurisdiction, if only as a warning to the Russian hierarchy that he, the Greek Patriarch, was all-powerful in his own territory of Jerusalem. In the same year, Fr Seraphim had to leave the Garden of Gethsemane and he found refuge at a small monastery within the grounds of Little Galilee at the top of the Mount of Olives, right next to the Garden of Gethsemane.

As time passed, Fr Seraphim’s attitude towards his former colleagues in the ROCOR Russian Mission softened and, at the same time, the position of Fr Seraphim in the Russian community was strengthened. Stegny reports that “His solitary, truly monastic lifestyle and the respectful attitude of the Greeks toward him continued to attract to Galilee Minor the inhabitants of the Russian monasteries in Jerusalem who came to him for spiritual advice and instruction.” [88] Stegny (2017). 244. By the early 1930’s Fr Seraphim was being invited to participate in various important events of the Russian community in Jerusalem, culminating in serving Divine Liturgy in Gethsemane with Metropolitan Nestor during his visit to Jerusalem in 1935. [89] Stegny (2017). 245. The 1923 deprivation of Fr Seraphim’s right to serve had been quietly forgotten. Indeed, it is clear from his book that Archbishop Nestor held Fr Seraphim in great esteem. [90]Aрхиепископ Нестор Анисимов, Святая Земля (Сирия и Палестина) (Archbishop Nestor Anisimov, The Holy Land [Syria and Palestine]). (Harbin, 1936). … Continue reading

From the papers of Fr Nicholas, it is discernible that Fr Nicholas and Fr Seraphim formed a close bond, united in their devotion to the memory of the Imperial Martyrs. A letter from Abbess Mary (Robinson) to Archimandrite Anthony (Sinkevitch), illustrates the point well. Presumably Fr Anthony had queried why Fr Seraphim was serving in Gethsemane on 4/17 July, the day of the martyrdom of the Royal Martyrs when Fr Nicholas was available to do this.

About the second part of your letter, I find it difficult to understand. Father Nicholas had a very special desire to serve his own Liturgy for his so dearly beloved family; he said that it must be private as he felt it all so very deeply, that he felt he could not attend a public function. [91]The clergy of the Russian Mission celebrated the memory of the Holy Martyrs in the large Mount of Olives Convent of the Ascension. Few people would be present at the church in the Garden of … Continue reading He would either have gone to Father Seraphim or Father Seraphim come here as they are both united in these intimacies with the Royal martyrs which bind their souls very close. But more than this, Father Nicholas feels this all so deeply that he frequently breaks down in the service with weeping and cannot continue, and then Father Seraphim helps. Here is the body of the sister of the Empress, here is the Royal Church and here were the two who had been closer to them than others. I cannot see that there was any division as both Mount of Olives and Gornya [Ain Karim] had their services and here even more a service was fitting. It was a wonderful service and all who were present felt the Communion with the Church Triumphant as never before. This weeping old priest who could not pray for tears was a vital part of that company of people who perished today for Holy Russia. How not to give him a Church to serve in and his own choice of priest to help him? He happily knows nothing of your feelings. Vladiko told me to try to give Father Nicholas no idea of the unhappy divisions existing between different members of the Russian Community here as it would make a very bad impression upon him to take to England. He loves Father Seraphim and I think that it is best not to touch this holy friendship. I asked Father Nicholas to go and see you but yesterday was such a day of anxiety for him over Fr Lazarus, that he may have forgotten. He could not continue evening service when he heard he was so ill. About Fr Seraphim: I only sent him the Letter during the evening service but Vladiko said that he could always serve in this Church when he cared, a permission he never takes advantage of, for he never serves here.

I am writing to Vladiko by this mail and I will tell him all my sin, for I cannot see how in the name of Charity and courtesy I could have done otherwise. I understood you to say only that if Father Seraphim served, he must be the second priest, which he was. [92] Letter dated 4/17 July, 1936. Archives of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem. (Kindly contributed by Dr. Petr V. Stegny.)

Then, a few days later, Fr Nicholas wrote to Miss ffrench in Harbin,

Tomorrow (Our Lady of Kazan) [8/21 July] …I am invited to celebrate at Little Galilee, where the Virgin and the Galileans are said to have lived. There are two churches there (it is the Greek Patriarch’s summer residence) and the small one has for its incumbent the Rev. Igoumen Seraphim, who brought the remains of the Grand Duchess and her nun to Palestine from Peking. [93] SNPA 20.07.1936.

A week later, in writing to Fr Dimitrii, Fr Nicholas mentions being invited to co-serve with Fr Seraphim on his Nameday:

On Saturday last [19th July/1st August, 1936], the name’s day of the incumbent of the small church on his domain, who is Russian, I was invited (by the incumbent) to assist at his celebration. When the Patriarch heard this, he said that he would be present and come and instead of assisting I had to celebrate. Of course, my papers are all in proper order but (owing to the Father Lazarus case) [94] See section below, ‘Hieromonk Lazarus (Moore)’. I didn’t get permission to serve in the Greek churches here for six weeks or two months after my arrival. However, when the Patriarch accorded me his mandate to serve anywhere in Palestine, he very kindly told Father Lazarus to be patient and he would also get his. [95] SNPA 31.07.1936.

Commenting on Patriarch Timotheus I, Fr Nicholas continued, “Fortunately, the present Patriarch is an exceedingly pleasant and amiable man with an Oxford education, but I suppose that even a Patriarch must go with the stream.”

On the same day Fr Seraphim gave to Fr Nicholas a number of relics, including portions of Great-Martyr St George; St Panteleimon; Great-Martyr Artemius; Great-martyr Theodore Stratelates; and Saint Hermogenes, Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia. Fr Nicholas was careful to obtain a certificate from Fr Seraphim, who confirmed that “These portions are taken from relics given to me by the Ecumenical Patriarch, Joachim III and by a Staretz on Mount Athos in 1908.” [96] SNPA 21.07.1936.

The Patriarch, through Fr Seraphim, invited Fr Nicholas to co- serve Divine Liturgy on the feast of the Holy Transfiguration (6/19 August, 1936) at the Patriarchal residence. Fr Seraphim wrote,

Tomorrow, August 6th, Archimandrite Silvester, prior of Saint Sabbas Monastery, will be serving the liturgy here together with me, and His Beatitude the Patriarch has given his blessing for you to serve with us, as well. He will be presiding. Come at 4:30 [a.m.], no later; the Patriarch will get here at 5:00 and the Liturgy will begin.

Three days later, at 3 p.m. on Saturday, 9/22 August, the Patriarch formally “received” Fr Nicholas at the Patriarchal summer residence, accompanied by Fr Seraphim.

After his departure from Palestine, Fr Nicholas continued to correspond with Fr Seraphim. As is well known, Fr Nicholas transferred his allegiance from the ROCOR to the Moscow Patriarchate in 1943. Two years later, in 1945, the Russian Patriarch Alexei I, during his stay in Jerusalem, visited Fr Seraphim at Little Galilee and formally received him into the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate. In 1959 Fr Seraphim died and was buried in Little Galilee.

Hieromonk Lazarus (Moore)

Now we must turn our attention to another Jerusalem priest with whom Fr Nicholas had much involvement, Fr Lazarus (Moore). Sometime after Mother Mary and Mother Martha had arrived in Jerusalem in 1933, they were joined by another English convert, the former Anglican priest, the Revd. Edgar Moore.

Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore).

Fr Edgar had travelled to India in 1933 where he was deeply impressed by an ascetic Russian Orthodox priest, Archimandrite Andronik (Elpedinskii, d. 1958). As a consequence, Moore decided to become Orthodox and in 1935 travelled to Jerusalem, intending to be made Orthodox in the Greek Patriarchate. The Greeks and the Anglicans conspired to thwart the conversion of Fr Edgar. With the blessing of Metropolitan Anastassy, instead Fr Edgar travelled to Belgrade where, almost exactly 12 months after Fr Nicholas had been ordained in far-away Manchuria, Fr Edgar was received by Chrismation into the Orthodox Church, tonsured as a monk, given the name “Lazarus”, and ordained as a priest by Archbishop Theophan (Gavrilov) of the ROCOR. The so-called “re-ordination” caused a huge scandal in the Anglican Church at a time when High Church Anglicans were keenly seeking recognition of the validity of Anglican orders by the Orthodox Church. Writing in The Christian East, Canon J. A. Douglas, Secretary for the Anglican Council for Foreign Relations, not without rancour, noted, [97] Canon J. A. Douglas, “The Metropolitan Antony and Anglican Orders,” The Christian East. 16. 3 and 4 (1936): 90.

Up to the present the majority of the Russian bishops in exile have held that they cannot adjudge the question of Anglican Orders, but that it must await decision so far as the Russian Church is concerned until the Russian Church as a whole can pronounce upon it. The Metropolitan Antony [Khrapovitskii] was otherwise minded and distressed at the decision of the Sremsky-Karlovci Synod in 1935… [that] an Anglican priest on acceding to Orthodoxy should be re-ordained.”

In 1936 Hieromonk Lazarus returned from Serbia to Jerusalem where he remained until the Arab-Israeli War. After 1948, Fr Lazarus became something of a wanderer, living variously in the UK, USA, India, Greece, Australia and eventually in Alaska, where he passed away in 1992 at the age of 90.

On returning to Palestine early in 1936, Fr Lazarus was appointed chaplain of the Bethany and Gethsemane community. He lived in Bethany and worked with Mother Mary in building up the community and the school. Fr Nicholas seemed to have had an ambivalent attitude towards the much younger Fr Lazarus. Writing to George in June, 1936, he commented, “There is one English priest but he is much younger than I and has a considerable number of corners. Being in the world has taken many of my corners off, thank goodness.” [98] SNPA 06.06.1936. In July, Fr Lazarus was taken into hospital, and, according to Mother Mary, on hearing that Fr Lazarus was so ill in hospital, Fr Nicholas could not continue the evening service, even though it was the Vigil for the day of the martyrdom of the Imperial Family. [99] Letter dated 4/17 July, 1936. Archives of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem. Indeed, Fr Nicholas wrote to Archbishop Nestor, “My English colleague (Rev. Father Lazarus) is a very nice young man and we have got on quite well together. He apparently intends eventually to go to the Orthodox Church in India.” [100] SNPA 20.07.1936. For Fr Lazarus, Fr Nicholas spent a considerable amount of his time in Jerusalem using his typewriter, putting together a manuscript of prayers in English, presumably a predecessor of the well-known Orthodox Prayer Book published for Fr Lazarus by Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, USA in 1960.

In November, 1936, the Jerusalem Anglican Archdeacon, Weston Stewart (d. 1969), who later became Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem, wrote a memorandum to Canon J. A. Douglas (d. 1953) in London about meeting Fr Nicholas: [101] LPL, CFR OC 206/1, ff. 01.

…His first visit to St. George’s [Anglican Cathedral] was a call on me… during which he was at pains, without any lead from me, to make clear that the circumstances of his ordination were in no way parallel to those of Father Lazarus (the Rev. Edgar Moore) and that he dissociated himself emphatically from the latter’s action.

Archdeacon Stewart then tells of an incident in which Fr Nicholas and Fr Lazarus called at the Anglican Cathedral Library to borrow some books.

…Feeling somewhat aggrieved at his reception at the Library (where he was not recognized but Father Lazarus was) he called on me again, partly to complain, and partly to explain. I intimated politely that since Father Lazarus, who was a resident, had never called or had any contact with the Anglicans at all, and was in fact rather an embarrassment to Anglo-Orthodox relations, it was unfortunate that he had gone to the Library first under Father Lazarus’ aegis. He saw the point, but said that since he himself was clearly the senior man (he holds I believe a rank equivalent to honorary Abbot) he did not consider Father Lazarus mattered. We parted on excellent terms.

On his final visit to the Anglican Bishop in November, 1936, “Fr Nicholas made it quite clear that relations between himself and Father Lazarus were even more strained than between himself and Mother Mary.” [102] LPL, CFR OC 206/1, ff.01. What caused that difficulty remains a mystery. In the same document Archdeacon Stewart summed up his impression of Fr Nicholas: “To me he seemed a kindly, gentle man, seeking spiritual peace and quiet, but overwhelmed against his will by the atmosphere of political and personal intrigue which hangs about the Russian Mission and the Russian Church.”

The Pilgrim

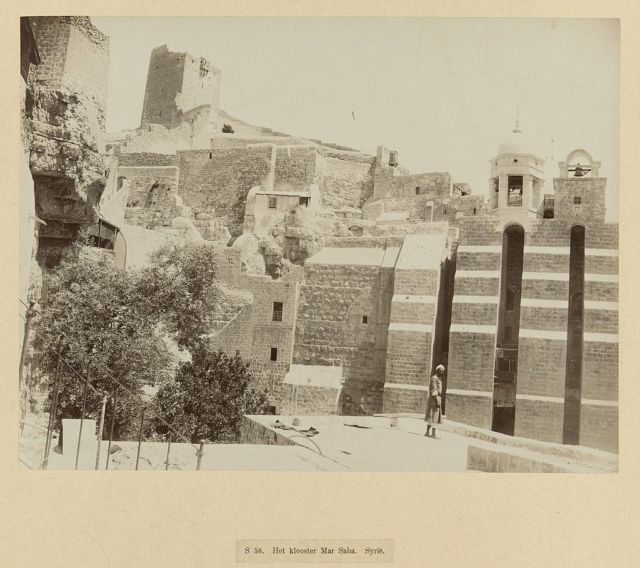

Towards the end of August Fr Nicholas decided to take matters into his own hands and not wait for the Arab Strike to end. He carried out the threat he made to his sister, Winifred, and did indeed go on foot (“at present our usual method of locomotion” [103] SNPA 04.09.1936. ) all the way to Bethlehem and back – a round trip of some twelve miles – despite his age (63), the intense heat, and possible danger. On the weekend of 12/13 September Fr Nicholas walked to the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Mar Sabba which overlooks the Kidron Valley, halfway between the Old City of Jerusalem and the Dead Sea, some six miles from Jerusalem. “In a moment of fright, I came back on a donkey, which on the whole is quite a pleasant method of transportation… though its chief advantage in the summer time is in keeping down the temperature of the rider and delivering the ‘goods’ in a ‘dry condition’ so to speak.” [104] SNPA 04.09.1936.

1937 photograph of Mar Saba Monastery.

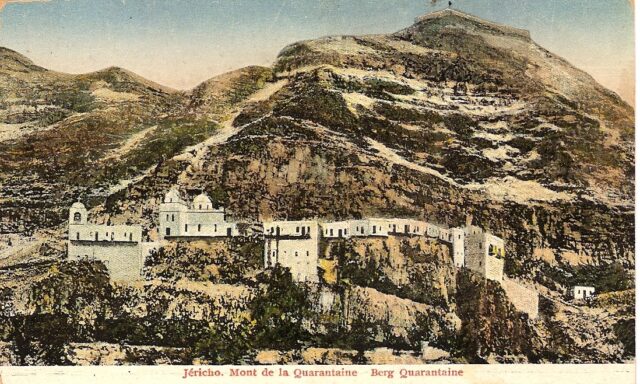

Fr Nicholas also managed to make a visit to the Jordan Valley, although he does not mention how he got there or with whom. Writing to George about the Jordan excursion, Fr George does mention that he paid 2/- for two persons in each of the three monasteries in which he stayed, and that the return fare was 3s/5d, [105] Here Fr Nicholas is using British equivalents to the Palestine currency. 2/- (two shillings) is about £7 today; 3s/5d (three shillings and five pence) is about £11 today. which suggests that he and his companion were able to hire a taxi, despite the Arab Strike. [106] SNPA 11.10.1936. On this visit Fr Nicholas bathed in the River Jordan “and acquired new health and strength thereby” [107] SNPA 04.09.1936. and visited the Greek Orthodox Monastery of St John the Baptist which is almost on the banks of the River Jordan. He also bathed in the Dead Sea, walked around the ruined walls of Jericho and visited the Greek Orthodox Monastery on the Mount of Temptation, which is on the slopes of a mountain overlooking Jericho and the Jordan Valley. In October Fr Nicholas wrote to George, telling him that he no longer suffered from the hernia which had afflicted him since leaving Harbin. “I have not yet shown myself to the doctor and I am wondering whether it is necessary for it is evidently the healing waters of the Jordan.” [108] SNPA 11.10.1936.

Monastery of the Temptation.

The night of 17th/18th September marked the 40th day of the passing of Metropolitan Anthony. The Head of the Russian Mission invited Fr Nicholas to join the other clergy in the Holy Sepulchre to pray for the late Metropolitan and also for the repose of the soul of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna. Beginning at 6 p.m., the prayers began with Vespers, followed by several akathists. At 10 p.m. there was a break of about an hour and a half, followed by Matins and, at about 1.30 a.m., the Divine Liturgy and a pannikhida. Finishing at about 3.15 a.m. the clergy had a cup of coffee and then rested until the doors of the Holy Sepulchre were re-opened at 5 a.m. Fr Nicholas recalled, “There are two or three bedrooms and, on this occasion, I slept on a divan in the office, which is under ‘Golgotha’, and adjoins the ‘Reliquary’, where there is a real ghost sometimes seen!” adding, “It is a wonderful experience however and invitations to serve on Golgotha are greatly prized.” [109] SNPA 18.09.1936. On the next day, Saturday, Fr Nicholas visited an “ancient Greek Monastery about 20 miles from Jerusalem”, probably the Monastery of St Gerasimos of the Jordan, where he stayed for the night services and then returned to Gethsemane.

The Arab Strike ended on 11th October, 1936 and on that same day Fr Nicholas once more walked to Bethlehem, stayed overnight and on the next day visited Solomon’s Pools, near to Bethlehem. The ending of the strike allowed Fr Nicholas to make the long-awaited trip to the north of Palestine, to Lake Galilee. With one of the fathers from the Russian Mission, Fr Nicholas travelled north on the 17th October and remained there for about two weeks.

In the same month, Fr Nicholas was invited to visit in Jerusalem the Armenian Patriarchate, where he was given a tour which included the Cathedral of St James and the place of his martyrdom, and where Fr Nicholas was “presented” to the Patriarch Torkom (Koushagian, d. 1939). Almost the last thing which Fr Nicholas did before finally leaving Jerusalem was on 20th November, 1936, when he visited Archdeacon Weston Stewart and attended a service at the Anglican Cathedral of St George. “I am on quite good terms with them [the Anglicans] and I am going to emphasize the fact by going to their church to service.” [110] SNPA 11.10.1936.

Future Plans

From his voluminous correspondence of 1936 we can learn something of what Fr Nicholas was planning for his future in England. He shared his plans with, amongst others, his good friend in Harbin, Miss ffrench, and with his mentor in Harbin, Archbishop Nestor. However, the most detailed account of his plans was shared with an English priest who in 1936 was living in Athens, Archimandrite Dimitrii (Balfour). Fr Nicholas had never met Fr Dimitrii but had heard much about him from Fr Lazarus who was in correspondence with Fr Dimitrii.

Archimandrite Dimitrii (Balfour).

Born in 1903, David Balfour became a Roman Catholic priest and lived in Rome. [111]Dr Nicholas Fennell, “An Englishman in the Eastern Orthodox Melting Pot.” Academia.edu.(2019) (5) (DOC) DAVID BALFOUR: AN ENGLISHMAN IN THE EASTERN ORTHODOX MELTING POT | nicholas fennell – … Continue reading In 1932 Fr David travelled to Mount Athos where he encountered Staretz Silouan, later St Silouan (d. 1938) and his disciple, Elder Sophrony, later St Sophrony the Athonite (d. 1993). This experience changed his life and Fr David decided to become Orthodox. He was received into the Orthodox Church in Paris by Metropolitan Elevtherii (Bogoiavlenskii, d. 1940) of Vilnius and Lithuania, Exarch of the Moscow Patriarchate, and ordained as a priest for the Russian Orthodox parish of the Three Hierarchs Church, Paris. A year later, he was tonsured to the small schema by Archbishop (later Metropolitan) Veniamin (Fedchenkov) of Sevastopol (d.1961) and given the name of Dimitrii. In 1934, Metropolitan Elevtherii sent Fr Dimitrii to London for six months to liaise with a group of English Orthodox in the hope of setting up a parish there but the venture failed from lack of support and money. After a brief return to Mount Athos, Fr Dimitrii settled in Athens where he lived from 1936 to 1941. While still under the jurisdiction of Metropolitan Elevtherii, Fr Dimitrii enrolled as a monk in the Monastery of Penteli in the north of Athens. Then Fr Dimitrii was made archimandrite by the head of the Church of Greece, Archbishop Chrysostomos, who appointed him as father-confessor at the Evangelismos Athens General Hospital. Fr Dimitrii, who took a degree in theology at Athens university and was awarded a first, was a brilliant linguist with expert knowledge of ecclesiastical Greek and Church Slavonic as well as being fluent in French, Italian, German, Greek and Russian. When the Nazis invaded Greece in 1941, Fr Dimitrii left Athens and went to Cairo. Subsequently Fr Dimitrii abandoned his Orthodox faith and priesthood, got married, and became a British diplomat. He was reconciled to the Orthodox Church in 1962 and passed away in 1989, at the age of 86.

In deciding to leave Harbin and return “home”, Fr Nicholas seemed to have a rather muddled view of possible future plans. For example, in a letter to Father Dimitrii Balfour he wrote that, “When I was in the Far East I began to try and map out the future and I came to the conclusion that it was very essential to endeavour to create cordial relations with the Greek Orthodox in London.” [112] SNPA 04.06.1936. Fr Nicholas had asked a young Greek man in Harbin for written introductions to the Greek clergy in London. Unfortunately, the unnamed friend could not give Fr Nicholas an introduction to the Greek priest in London since he did not know them personally. However, he did give Fr Nicholas introductions to, amongst others, an archimandrite in Paris, a layman in Corfu, and the Greek Prime Minister. It is difficult to understand why Fr Nicholas thought that relations between the Greeks and the Russians in London were anything but “cordial”, nor why he thought that it was “very essential” he should be involved in such matters. Of course, Fr Dimitrii had been made an archimandrite of the Church in Greece; for many years Fr Nicholas entertained the hope that Fr Dimitrii would join Fr Nicholas in his various ventures in England and perhaps somehow this was a tactic to engage the interest of Fr Dimitrii.

In the same letter, Fr Nicholas then comments,

Until I have been to England and had a good look round, I am not making any definite plans for the future and I shall be delighted to have the opportunity of discussing things with you. I have felt that the time is hardly yet ripe for an English Orthodox Church on parochial lines, [sic] and what Father Lazarus tells me of your experience in London seems to bear this out. I am inclined to think that a small religious Orthodox house (community) in England would have a better chance of success. Have you considered such a project? I have been warned by experienced fathers in Harbin that the difficulties of starting a monastery are immense and one of the fathers very strongly stressed the desirability of beginning with a convent of Orthodox nuns. The advice may be sound and the one, of course, does not exclude the other, within limits. [113] SNPA 30.07.1936.

Fr Nicholas then goes on to tell Fr Dimitrii that he is collecting “everything necessary to start an Orthodox Church” but his biggest need is for liturgical books, both Slavonic and English. He says that he is hoping to get what he needs either on Mount Athos or from the Serbian Patriarch. “… I do NOT expect the books to be given away [sic]. I only pray that the owners may be reasonable. In Harbin often they were not!”

In June, writing to George, Fr Nicholas tells his adopted son that Abbess Mary and Mother Martha had been trying to persuade Fr Nicholas to first go to England and then return to Gethsemane and serve as a priest there. “I have told them definitely that I can hardly contemplate making the convent my permanent home, so I have told them definitely that I am going to settle myself in England.” [114] SNPA 12.06.1936. Later in the same letter, Fr Nicholas makes the intriguing observation that, “I have made here the acquaintance with a number of members of the western church. I could stay here in Palestine if I wanted to do so. But I have declined the invitations, one of which was quite pressing.” [115] SNPA 12.06.1936. Whether or not the pressing invitation was the one from Mother Mary or in fact was from a member of the Anglican church remains unclear. He also asks George: “I am wondering how I shall dress in England? Have you seen how the Orthodox clergy dress in London?” [116] SNPA 12.06.1936. In his reply George confessed ignorance on the point but he had asked a certain Mr Kilin who thought they wore black gowns which he thought were called a riasson. [117] SNPA 15.06.1936.

Stourmouth House Farm with oast house.

Pursuing the idea of founding a monastery in England, Fr Nicholas suggested to Fr Dimitrii that the property that he had purchased recently would serve the purpose. Fr Nicholas describes in great detail the 17th century house in Stourmouth, near Canterbury in Kent, which had six small bedrooms and four additional rooms in the attic. He ponders, “Would it be possible to run this as a “Retreat House” for Orthodox and Anglicans?” Fr Nicholas thinks that, to begin with, the drawing room could serve as an Orthodox church. Alternatively, “we could build a small church on to the house adjoining the drawing room” and the drawing room would become the narthex. “I have brought with me from the Far East everything necessary for a church.” He mentions that he has sixty or seventy icons, all purchased for “their beauty, their origin, or their antiquity.” Some of the icons have been “packed up for about ten years.” He then goes into minute detail about having copies of the Gospels bound in an Orthodox manner. To this lengthy letter, Fr Nicholas adds a postscript:

Since writing the above I have been thinking that possibly the old oast house would make a good temporary chapel. The building itself is, I am told, in a very bad state of repair, but perhaps for a church we could collect money from somewhere. Most of the English monastic houses seem never to make any appeals for money, which means that they get just as much (and possibly more) than they require.

He then considers how they could support themselves by using the produce of the farm attached to the house and by generating a small income from holding retreats: “If God has already provided a house and food, one can hardly doubt that He will also provide money and people too.”

Fr Nicholas gave consideration as to the dedication feast of the monastery/retreat house. He remarked to Ms. ffrench,

I am thinking of dedicating my Monastery in honour of the Uspensky Feast, what do you think? It has many attractions and one of them is that it falls in the month of August, the month of plenty and it never comes at a time of fast, and a great many people have holidays at that time. Moreover, it is a festival particularly esteemed by Russians. Otherwise, I should like to commemorate the, I should say ‘our’, martyrs.

Just before ending his lengthy July epistle to Fr Dimitrii, his hopes of Fr Dimitrii joining him in Stourmouth were dashed by Fr Lazarus.

Since writing the above I have had a talk with Father Lazarus and he tells me that I am under a misimpression. That your studies will not be completed until the year after next [i.e., 1938]. However, on thinking it over, I decided to let this letter go as it is, for it will have to serve as our “interview” for the moment. If you remain in Greece for that length of time you may nevertheless come to us at least once in vacation time if you feel inclined.

Between 1937 and 1940, Fr Nicholas wrote to Fr Dimitrii on several occasions, repeating his invitation, but all to no avail. Fr Dimitrii never did visit Fr Nicholas in Stourmouth.

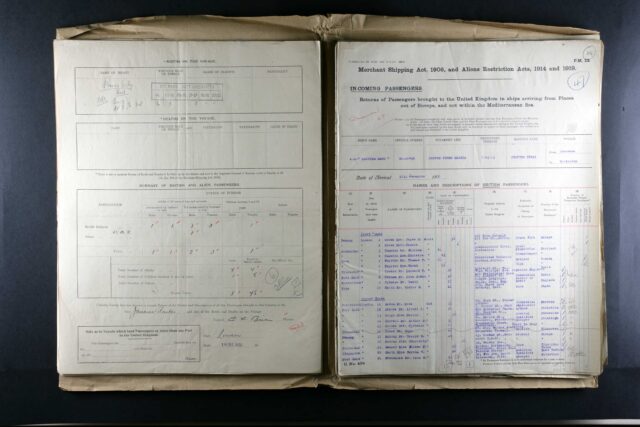

Homeward Bound