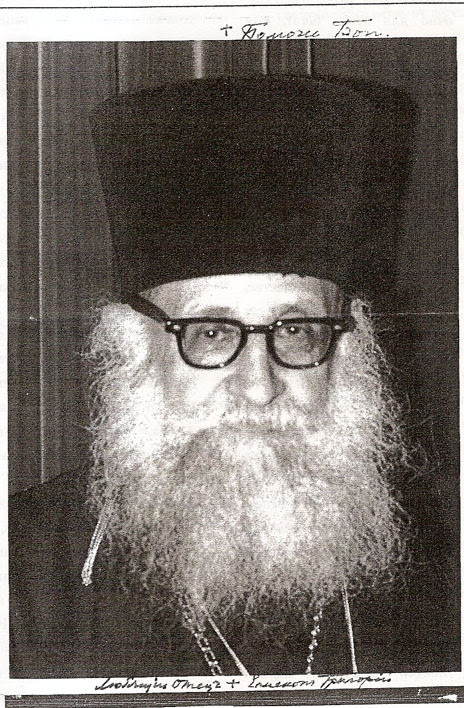

Bishop Gregory (Grabbe) passed away on this day in 1995.

Count Yuri Pavlovich Grabbe was born into a practicing Orthodox aristocratic family in Saint Petersburg in 1902. The Russian Slavophile, philosopher, and lay theologian Aleksei Khomiakov (1804–1860), was his maternal great-grandfather.

The future Bishop Gregory was a very consistent man. I have read both his diaries, which he kept during the Russian Civil War as Yuri Pavlovich, and letters he wrote later as Bishop Gregory. What struck me was that he was the one and the same person all along. One would not find it hard to believe that the same “old Grabbe” who authored the letters also kept this journal.

This permanence was one of Bishop Gregory’s strengths. He did not suffer from an inferiority complex. During the ROCOR Bishops’ conference in Vienna in 1943, Count Grabbe was bold enough to ask an SD (Sicherheitsdienst, the Nazi intelligence service) officer to leave the room. In America, he did not have any problems discussing matters privately with an “ideological enemy” of his, Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann.

Reflecting on one of these meetings, Fr. Alexander wrote in his diary on December 12, 1973, “[T]he Karlovites really have a style – and not just ‘stylization,’ but this makes any conversation with them so difficult because style excludes the possibility of simply understanding, hearing what is outside this style and calls it into question.” All that I wrote above makes me think something about Bishop Gregory along the lines of the assessment of Synod Oberprocurator Konstantin Pobedonostsev (1827–1907) by the Russian philosopher Konstantin Leontʹiev (1831–1891): “He is a helpful person; but how? It is like frost: it prevents further rotting, but nothing will grow with it. He is not only not a creator, but not even a reactionary, not a restorer, not a reconstructor, he is only a conservative in the closest sense of the word; frost, I say, a watchman, an airless tomb, an old ‘innocent’ girl and nothing more!!” (Letter to T.I. Filip’ev, Pamiati K.N.Leont’eva [Remembering K.N.Leont’ev], Saint Petersburg, 1911).

It is obvious to me how helpful Bishop Gregory was to the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. He ran the chancery of the ROCOR from 1931 until 1986. Count Grabbe was unmercenary, and I cannot imagine how difficult it might have been for his wife to raise their four children on his more than modest income.

Part of that style mentioned by Fr. Alexander was the administrative system that the Russian refugee church had developed by 1959 in the US. Fr. Alexey Ohotin recalled how it was on a practical level: “At the end of September, Protopriest George Grabbe telephoned me and said that Vladyka Metropolitan asked to tell me that the following Sunday I would be ordained to the priesthood and assigned as rector of St Nicholas Church in Poughkeepsie” (“I am Going to Jordanville, No Matter What.” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad).

At the same time, this conservatism without creativity in merely a preservationist sense led to triumphalism, double standards, and isolationism. Unfortunately, the last quality was manifested in the end of Bishop Greogry’s life story: he asked that no bishops from the church that he had served most of his life be present at his funeral.

Relevant Links:

“Correspondence between Fr. George Grabbe and N.M. Zernov,” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.

Frs George Grabbe and Vladimir Rodzianko, “The Eucharist Does not Depend on Jurisdiction: Conversation across Countries and Epochs,” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.

Yuri P. Grabbe, “At the Twilgiht of Jewish Power,” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.

“Protopresbyter George Grabbe’s Correspondence with Archpriests Georges Florovsky and Alexander Schmemann,” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.

Archpriest Arkadii Makovetskii, “The Role of Bishop Gregory Grabbe in Establishing Parishes of the Russian Church Abroad in the Canonical Territory of the Moscow Patriarchate (1990–1995)” Historical Studies of the Russian Church Abroad.

His wise and gentle counsel gave me the greatest of comfort. I still have the letters he wrote to me. Thank you.