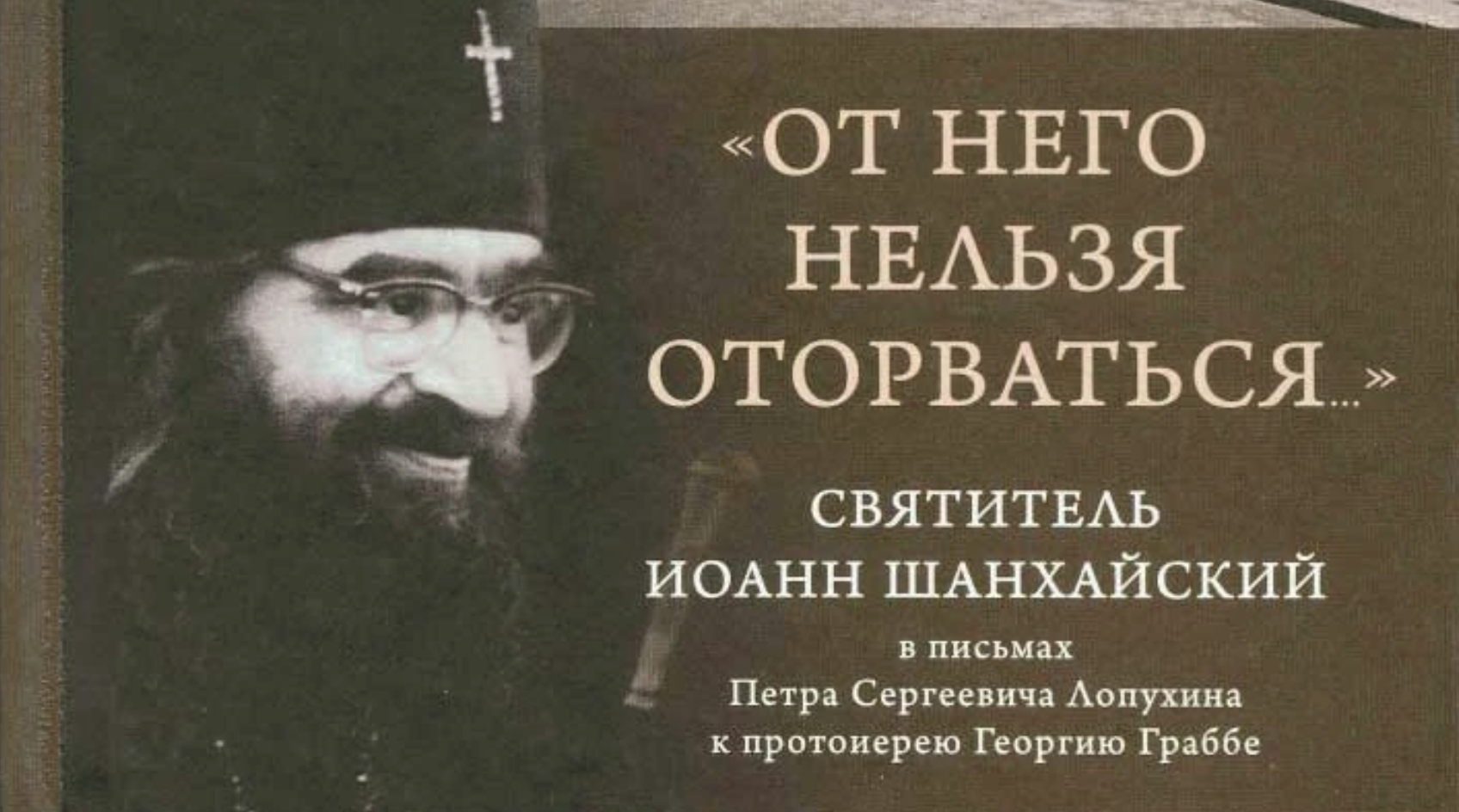

I bought this pamphlet in 1998 at the Alexander Nevsky Compound in Jerusalem. This piece had been written at the time of the heated debates around autocephaly granted by Moscow Patriarchate to the North American Metropolitanate. The All-Russian Council elected the new Patriarch, Pimen, in 1971 and also issued this autocephaly. Responding to the notion that the Moscow Patriarchate was the Mother Church to the North American Metropolitanate, the Russian Church Abroad, at its Bishops Council assembled in Montreal later in the same year, stated that the Mother Church for the Russian Church Abroad was the Underground Church, which did not recognize the canonicity of the Moscow Patriarchate

As a result of the decision to receive autocephaly from “the Soviet Church,” several clergy and parishes left the Orthodox Church in America. These communities were divided, and lawsuits for the right of property ownership followed. Probably the most famous one was over the church in the name of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in Sea Cliff on Long Island in New York. Fr. Alexander Schmemann and Fr. John Meyendorff represented the OCA; Fr. George Grabbe and his legal team represented the ROCOR.

This work, published as a pamphlet by Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem in 1971, responded to the challenges of that time. One of the lines of arguments in the pamphlet and at court hearings was that, since Moscow Patriarchate did not have rights of legal corporation, it was the Soviet state and not the Church that had approved the decision to issue autocephaly to the Metropolitanate. Fr. George Grabbe, at the time of writing the pamphlet, was the only canonist in the Russian Church Abroad. Although his essay bears strong characteristics of polemical writing, some of the facts and points remain valid for historical reconstruction, for understanding the position of the ROCOR in particular, and generally the extraordinary canonical reality of the twentieth century.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev, March 28, 2023

I. Introductory Remarks

The election of a new Head of the Moscow Patriarchate again confronts the Christian world with the question whether the person bearing the title “Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia” is indeed the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, or whether he is a mere pretender to that title and position, having in reality no canonical and no legal rights such as would normally be his due.

One may argue that this question is raised by us unnecessarily, since patriarchal elections have already taken place twice in Moscow in the presence of many representatives of other local Orthodox Churches and, by virtue of the fact of their representatives having witnessed them, these elections have already acquired general recognition. The civil authorities have both permitted and recognized these elections, thus providing them with a “legalization” of sorts.

We shall deal with the legal status of the Moscow Patriarchate at the end of this treatise. At this point we shall begin by clarifying the question as to whether the mere fact of the presence of representatives of other autocephalous Churches is in itself sufficient proof of the legitimacy of these elections, and whether or not this presence is such an authoritative proof of legality that it eliminates the need to enquire into other aspects of the matter.

After the death of Patriarch Tikhon, from the time when it was headed by Metropolitan Sergei (Starogorodsky) until the year 1943, the Moscow Patriarchate remained isolated from the rest of the Orthodox world. The Soviet authorities kept the Metropolitan under conditions that permitted him only a bare minimum of contact with the outside world. Correspondence with the heads of other Churches was practically non-existent, and none of the Moscow bishops was permitted to travel abroad to maintain personal contact with the Churches of the Free World. It was not until towards the end of World War II that the Soviet rulers realized that the Church could be of use in their foreign policy. From that time on the situation changed. With the election of Metropolitan Sergei to the position of Patriarch in 1943, and even more noticeably after his successor Metropolitan Alexei (Simansky) had been elected Patriarch, the relations of Moscow with the Eastern Orthodox world entered a new phase.

These new relations began with the presence of the representatives of many local Orthodox Churches at the Moscow Church Council held in 1945, and were intended to denote general recognition of the new election of a head of the Russian Church. The presence of these representatives was supposed to give the election canonical legitimacy, a legitimacy that was definitely established and not open to question.

It was intended to advertise, to a certain extent, the so-called freedom and prosperity of the Church in the atheistic communist state. The more these outwardly satisfactory (or seemingly satisfactory) conditions could be emphasized at the election of a patriarch, the more profit could be derived from such an election to serve the interests of Soviet foreign policy in the future.

That is the political importance of the presence of many Church representatives at such a Council, however no canonical significance whatsoever may be attached to it. The presence of these Church representatives can in no way be considered as a factor giving these elections canonical force. During the unopposed election of Patriarch Tikhon there were no representatives of other Churches present. Given the fact that this election was carried out legally, it would have been valid regardless of the number and rank of the invited guests of honor who witnessed it. If an election is held illegally, however, no such presence can make it legal. For instance, no matter who is present at the performance of an ordination or consecration that violates the canons on simony [1] The obtaining of ecclesiastical preferment by means of bribes, or the buying and selling of ecclesiastical rank. (Apost. 29; IV Ecum. 2; VI Ecum. 22 and others), or that takes place through the interference of the civil authorities (Apost. 30; VII Ecum. 3), — no matter who he may be, his presence at, or even participation in such an act does not convey to it any canonical validity.

The representatives of other Churches did not have and could not have any right of vote at the election of a Moscow Patriarch, nor could they have had any control over such an election. Their only function was to be present as guests of honor at the solemn festivities during the election of a person who was presented to them as the new head of an autocephalous Church. The most distinctive feature of autocephaly is the complete independence of the autocephalous Church in the election of its head, carried out exclusively and independently by the hierarchy of that Church, and not requiring the approval of any other hierarchy.

For this reason it has never been customary in the East to invite bishops of other Churches to be present at Church Councils electing patriarchs. This custom was introduced only recently by Moscow in order to create the outward impression of an unanimous and undisputed election, an election approved and accepted by everybody present. But the very fact that such a ruse is needed points to a dubious element in the legality of these elections, first of the Patriarch of Moscow, Alexei and now of Pimen. This dubious element is glossed over and there is the evident hope that it can be eliminated altogether by introducing added pomp and circumstance to the elections.

It is impossible to overlook the fact that all this glitter and pomp is created mostly by the Soviet Government, which allocates special funds, provides living quarters for the invited guests, and caters for them during their stay in the USSR. And yet this Government, as everyone knows, represents the communist party which has an important plank in its platform — to fight religion with all possible means until it is completely extinct. This applies to all religions in general and to the Orthodox Church in particular.

II. The Origin of the Present-day Moscow Patriarchate

The sainted Patriarch Tikhon died on Annunciation Day in 1925. Foreseeing the difficulties which were bound to arise in connection with the electing of a new head of the Russian Church after his death, the Patriarch had prepared a will in which he indicated the names of three metropolitans, to one of whom his authority should be transferred until it was possible to hold patriarchal elections in a legal manner as prescribed by the All-Russian Church Council of 1917-1918. On the strength of that document, one of the three Metropolitans named in Patriarch Tikhon’s will, Metropolitan Peter (Krutitsky) became “Locum Tenens” of the Moscow Patriarchal Throne. The candidates who were named before him in the will were: the Metropolitan of Kazan, and the Metropolitan of Yaroslav, Agathangel, who were then already imprisoned. Following the example of Patriarch Tikhon, Metropolitan Peter also named four candidates to his succession, the last in the list being the Metropolitan of Nizhny-Novgorod, Sergei. After the arrest and imprisonment of Metropolitan Peter, who was subsequently replaced by several consecutive hierarchs, each of whom in turn also named their successors, the mantle of “Locum Tenens” fell to Metropolitan Sergei in 1927.

Metropolitan Peter took a firm stand on the matter of the independence of the election of the head of the Church, which, he insisted, should remain free of any interference on the part of the Soviet authorities in the internal affairs of the Church. His successors adhered to the same principle and held their ground, and as a consequence were arrested one after the other. In the meantime the civil authorities endeavored to entice them away from their unbending position by offering them certain facilities which could be obtained for the Church at the price of a number of compromises, including an agreement to cooperate with the Soviet Government. The older hierarchs understood chat such offers were intended as a bait meant m fact to put the Church in a position subordinate to, and actually dependent upon the civil authorities. It was clear to them that they were dealing with sworn enemies of the Church. They understood that any compromise on their part would inevitably place the Church in a humiliating position in the future, the same as that in which the “Renovationists” found themselves. The latter were reduced to the role of agents whose only right was to praise the Government and to extol Soviet rule.

Thus Metropolitan Cyril, Metropolitan Peter, Metropolitan Agathangel, Metropolitan Joseph, Archbishop Seraphim of Uglich and many others of the senior hierarchs of the Russian Church refused, one after the other, any kind of agreement with the Soviet authorities.

Metropolitan Sergei at first prepared a declaration written in the same spirit as those of the other hierarchs who filled the post of “Locum Tenens”. However, after prolonged incarceration he published, on July 16/29, 1927, a declaration written in a totally different spirit. In it he promised obedience to the political authorities. In addition to this he constituted a Synod of Bishops composed entirely of persons of his own choice. Those who disagreed with the declaration and who objected against the canonical validity of the new Synod, whether they were bishops or priests, were put into prison as disloyal elements, just as were the so-called followers of Patriarch Tikhon. This procedure was applied to all those who remained loyal to the Patriarch and true to his principles as against those who pledged obedience to the civil authorities and toed their line. The latter were called “Renovationists” and were favored by the Soviet Government.

Once more the Church was divided. The oldest bishops accused Metropolitan Sergei of having abused the trust put in him by Metropolitan Peter, saying that he had overstepped his authority that, by making a pact with the atheistic government, he had become a traitor to the Orthodox Faith. Many bishops broke off communion with him and, being persecuted by the civil authorities, began organizing a secret Church known as the “Catacomb Church”.

The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, then headed by Metropolitan Anthony, adhered to their point of view. As long as Metropolitan Peter was alive, the Church Outside of Russia recognized him as the head of the Russian Church. But Metropolitan Sergei, who had compromised the Church to the Soviet authorities, was no longer recognized by that Church as the lawful successor of Metropolitan Peter.

In the meantime, Metropolitan Sergei, who had undertaken his rule in rather modest fashion, began to make many demands which not only undermined the morale and religious foundations of the Church but were contrary to the sacred canons.

This question was debated in detail during the drafting of the resolution passed by the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia on March 30/April 12, 1937, after the news of the death of Metropolitan Peter was received. Under lying that draft were two canonical investigations of the question. They were: my own note, prepared at the request of the President of the Synod, and the note of a professor of canon law, S. V. Troitsky. (Troitsky, having remained in communist territory, subsequently wrote a book in a completely different spirit from that in which he had previously been accustomed to write. This book is entitled “The Lie of the Karlovtsy Schism” (Paris, 1960). However, I irrefutably demonstrated the falsity of his book in my reply to it in “The Truth About the Russian Church in Russia and Abroad” (Jordanville, 1961). I have shown that Mr. Troitsky, in his book, merely kept silent about what he had written earlier, but was not able to refute it. The considerations he voiced while he was free therefore retain their validity as proof.)

Of particular importance is an article written by Metropolitan Sergei himself which serves as the best proof of the canonical irregularity of his own activities. The article is entitled “On the Powers of the Patriarchal Locum Tenens and his Deputy”, published in issue №1 of the ’’Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate” in 1931. It was reprinted in 1933 in issue No. 7 of the Paris magazine “Orthodoxy”, published by Archbishop Benjamin.

Metropolitan Sergei was an outstanding authority on church administration and a master of the finest shades of expression as far as canonical problems were concerned. In his article he begins by pointing out the difference between the title “Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne” and the title “Patriarchal Locum Tenens”. The author explains that the power wielded by the “Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne” in normal times is very limited. He appears as the temporary “advocate” of the Church but does not have the authority of a patriarch — for the very reason that he is elected to fill the gap until the election of a patriarch. “Nor does he enjoy the fullness of patriarchal power because he remains a member of the Synod and its representative, and is entitled to act exclusively on the authority of the Synod and in conjunction with it”. This limitation of power is emphasized by the fact that “the Locum Tenens does not enjoy the right reserved to patriarchs of having his name proclaimed in all churches of the Patriarchate, nor does he have the right to address, in his own name, messages to the flock of All Russia. The source of the power of the “Locum Tenens” is the Synod, “which may at any time transfer this power to another person of the same rank”.

On the other hand, as Metropolitan Sergei points out, Metropolitan Peter received the power of “Locum Tenens” “not from the Synod, but directly from the Patriarch”. ”It is significant”, writes Metropolitan Sergei, “that at the death of the Patriarch, all that was left of the project for a vast establishment made at the Council was the Patriarch … The existing Synod, consisting of three archbishops, and later of three metropolitans, was constituted by the personal invitation of the late Patriarch and lost its authority with his death. Thus, there was no institution parallel to the Patriarch and possessing sufficient authority entitling it to assume that authority and power in order to elect a “Locum Tenens”. The Patriarch filled that lacuna by making a will”.

“The will,” Metropolitan Sergei continues, “does not confer the specific title of “Locum Tenens” upon the person designated to wield patriarchal powers in the future, which designation might have given rise to equating him with an ordinary “Locum Tenens”. According to the spirit of the will, he ought to have the title “Patriarchal Vicar” or “Patriarchal Vice-regent”. The title “Locum Tenens” was assumed by Metropolitan Peter on his own initiative.

Metropolitan Sergei points out, and this fact deserves special attention, that “the late Patriarch, when he, by his own decision, transferred the patriarchal authority, owing to the prevailing circumstances, did not so much as mention by a single word the chair of the Moscow Patriarch. It remains vacant until this day.

“We shall add for our part that as far as pertains to his theoretical status, Metropolitan Krutitsky is to assist the Patriarch in the ruling of the Moscow diocese, but that as a matter of fact he rules it … In the event of the Patriarch’s death he is the natural temporary head of that diocese, no matter who is elected by the Synod as “Locum Tenens”. In case of the death or arrest of Metropolitan Krutitsky, the administration of the Moscow diocese should be taken over by the suffragists of that diocese in the order of their seniority, but not by the “Locum Tenens”, if he should be a bishop of another diocese.”

As far as the extent of the power vested in the Deputy “Locum Tenens” is concerned, Metropolitan Sergei considers that “the deputy is to have power to the same extent as the “Locum Tenens” for whom he serves as deputy. The difference between the “Locum Tenens” and his deputy lies not in the extent of the patriarchal power exercised but in the fact that the deputy is a kind of assistant parallel to the “Locum Tenens”. He retains his authority for as long as the “Locum Tenens” remains in function. With the cessation of the functioning of the “Locum Tenens” (whether by reason of death, withdrawal from responsibilities or whatever), the deputy automatically loses the power vested in him. It is naturally understood that with the return of the “Locum Tenens” to power, the deputy ceases to rule”.

Let us emphasize two important premises in the conception of Metropolitan Sergei.

- Metropolitan Sergei admitted that without a patriarch the chair of Moscow remains vacant. The election to that chair of a new patriarch reverts to the competence of the Local Ecclesiastical Synod.

- The Deputy “Locum Tenens” retains his authority only for as long as the “Locum Tenens” remains in his post.

In practice Metropolitan Sergei violated both of these principles. This question, as already mentioned, was the subject of detailed discussions by the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia after it was informed that Metropolitan Sergei had begun to call himself Patriarchal “Locum Tenens”. For the possession of that title, according to the opinion expressed by Metropolitan Sergei himself, he should have had the special authorization of Metropolitan Peter. As there was no such authorization, he should have relinquished the position. On the contrary, he added the title of “Locum Tenens”, to the title of Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna, which he had assumed on his own authority. That was done with the “ukaz” of December 27, 1937, which contained no reference to the death of Metropolitan Peter and which entirely omitted to mention the procedure whereby the Metropolitan had been given the title of “Locum Tenens”, but ordered his own name to be mentioned in prayers according to the newly established form.

The resolution of the Synod of Bishops of March 30/April 12, 1937, expressed dismay at the state of affairs then obtaining. That resolution recalled that Metropolitan Peter, having named four “Locum Tenens” in a statement made on December 6th, 1929, had made the following stipulation: “The proclaiming of my name as Patriarchal “Locum Tenens” during services remains compulsory”. In a letter of April 9/22, 1926, according to the very words of Metropolitan Sergei, he (Metropolitan Peter) “declared unequivocally that he considers it his duty to remain the “Locum Tenens” even though he be imprisoned”. (Letter to Metropolitan Agathangel of April 17/30, 1926).

Having assumed the administration after the arrest of Metropolitan Peter, Metropolitan Sergei at first used to sign his statements as follows: “for the Patriarchal Locum Tenens”. Subsequently, and on his own initiative, he began to call himself the “Locum Tenens”. Nevertheless, he considered himself to be the personal deputy of Metropolitan Peter. It is clear from the above words of Metropolitan Sergei that he admitted that when the “Locum Tenens” relinquished his post whether by reason of death, refusal to continue in that capacity, or whatever “the authority of his deputy ceases”.

“It is clearly indicated”, the same resolution of the Synod of Bishops goes on to say, “that in case of the death of Metropolitan Peter, Metropolitan Sergei may not presume to head the Russian Church; and that is because, as he himself admits, his own authority ceases with the demise of the person by whom that authority was conferred”.

The decision of the Synod recalls that in 1926 Metropolitan Sergei had himself written to Metropolitan Agathangel as follows: “Besides, the will of the Holiest, (i.e. Holiest Patriarch; “Holiest” in Russian is often used by itself to mean Patriarch), although it has already served its purpose (i.e. we have a “Locum Tenens), has not lost even now its moral and, let us also say, compulsory canonical force. And should Metropolitan Peter for some reason or other relinquish the post of “Locum Tenens”, he shall naturally turn to the candidates named in his will; that means — to Metropolitan Cyril, and after that to Your Reverence. I have already expressed this opinion of mine earlier in writing. I may say that it is the same as that of Metropolitan Peter”.

One would think that having made these declarations, Metropolitan Sergei might have given some explanation when he assumed his new title, pointing to the canonical law that justified it. It was his duty to inform his flock of the demise of Metropolitans Peter, Cyril, Agathangel, and Arseny, or else to produce statements of theirs (had they been available) publicly declaring that they refused to head the Russian Church. But for him to assume the title of Patriarchal “Locum Tenens” as well as the title of His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna without giving any explanation is nothing more nor less than the usurpation of titles and an authority that did not belong to him. What makes this particularly noticeable is the fact that he assumed the title of His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow (which took place on April 14/27, 1934) at a time when he was still holding the title of Deputy “Locum Tenens”. Though only a deputy at that time, Metropolitan Sergei clearly showed by his action that he was putting himself above the person for whom he was deputed to serve. Besides that, this title eliminated, to a certain extent, the temporary character of the powers of “Locum Tenens”.

Such an inference is also in conformity with the conclusion of Metropolitan Sergei’s present apologist, S. V. Troitsky. In his note submitted on April 11, 1937, to the Very Reverend Metropolitan Anastassy, Mr. Troitsky wrote very convincingly: “It is a legal axiom that the powers of the “Locum Tenens” cease with his death”. This was acknowledged “expressis verbis” by Metropolitan Sergei himself. Therefore with the death of Metropolitan Peter the authority of Metropolitan Sergei came to an end, and the post of “Locum Tenens” becomes automatically “eo ipso” occupied by Metropolitan Cyril, whose name should be proclaimed during services. Against this view there could be but one objection, namely, that Metropolitan Cyril, judging by the situation, will not be given the opportunity to assume the title and carry out the duties of “Locum Tenens”. Metropolitan Sergei, on the other hand, will not refuse the function of temporary head of the Russian Church. It appears, therefore, that in order to preserve the administrative unity of the Russian Church, it is not Metropolitan Cyril but Metropolitan Sergei who ought to be acknowledged and his name proclaimed. And yet such an objection would be erroneous. The possession of a right does not depend upon its exercise, but rather the reverse — the exercise of a right depends upon the possession of that right. It therefore follows that it is Metropolitan Cyril who is the legal “Locum Tenens”, the first (Russian) bishop of the people (Apost. Canon 34), even though he may be prevented from exercising his rights.

“One may not sacrifice legality for the sake of administrative unity. Metropolitan Sergei, by declaring himself ‘Locum Tenens’, would repeat the mistake he already made earlier by acknowledging the power of the ‘Living Church’ ”, and by such an act would have assumed the role of this Synod. The Russian Church had already found itself in a similar situation once before, after the exile of “Locum Tenens” Metropolitan Agathangel. Metropolitan Agathangel, however had not been lured into preserving the unity of administration at the price of recognizing the “Living Church”. Instead, he authorized all dioceses to form temporarily independent administrations, i.e., to restore the same order as existed in the Church during the first centuries of Christianity when the Christian Church was being persecuted. That order, issued by Metropolitan Cyril, would of necessity retain its full force even in the event of his being precluded from the possibility of actually heading and ruling the Russian Church. Even in such a case the proclamation of his name would remain an absolute duty.”

The Synod of Bishops, in part, enlarged upon the arguments of its two counselors. Having weighed all aspects of the matter, the Synod, in its resolution, discussed a possible argument that might be brought forward by Metropolitan Sergei against the recognition of the right of Metropolitan Cyril to the post of “Locum Tenens”. The Synod discussed the premise that the canonical rights of Metropolitan Cyril could be invalidated by the interdict imposed on him by Metropolitan Sergei for his refusal to agree with the measures taken by the latter.

The Synod of Bishops found that the steps taken by Metropolitan Sergei had been criticized by Metropolitan Cyril and many other authoritative hierarchs only because they jealously guarded the purity and the rights of the Church, and not for any other consideration.

“Their disavowal and protests, “says the Synodal resolution, “could not have brought them any advantage; on the contrary, these were acts of “profession de foi“ (confession of faith) that brought down upon them increased oppression and further exiles. Metropolitan Sergei’s imposition of interdicts on them, therefore, (even if this type of interdict could be formally justified by numerous — though in this case irrelevant — quotations from the Church canons) cannot be accepted as just by the conscience of the Church. Besides, Metropolitan Sergei had no right to inflict punishment on Metropolitan Cyril for his disagreement with the order of Church administration set up by Metropolitan Sergei because he, Sergei, was an interested party in that controversy, concerning which he kept up a polemical correspondence with Metropolitan Cyril. Thus, the suspicion naturally arises that he was simply seeking to tarnish the latter’s reputation in order to deprive him of his lawful right to head the Russian Church. Metropolitan Cyril, therefore, in no way deserves to be deprived of the title of “Locum Tenens” as a consequence of the interdict issued by Metropolitan Sergei; on the contrary, it is rather Metropolitan Sergei who should be removed in the event that the information concerning Metropolitan Peter’s will should be confirmed. That will allegedly named Metropolitan Sergei among the candidates to the post of “Locum Tenens”. Metropolitan Sergei may not be acknowledged as “Locum Tenens”, however, if only by reason of the fact that he has abused the power that was vested in him, having assumed the title of His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna. This act not only means that he has usurped the Patriarchal diocese, which, as Deputy “Locum Tenens”, he was bound to administer only temporarily until the election of a legal hierarch to fill that post (namely, Patriarch of All Russia); but such an act also undermines the entire order of patriarchal rule as established in the Russian Church by the All-Russian Church Council in 1917-18.”

In other words, the Synod of Bishops Outside of Russia found clear indications in the activities of Metropolitan Sergei of the usurpation of rights that were not his, and especially of the right to head the All-Russian Church. The usurpation was proved by the fact that Metropolitan Sergei announced the termination of Metropolitan Peter’s function of “Locum Tenens” by reason of the latter’s death only after he had assumed those rights himself. As was pointed out earlier, he condemns himself by his own statement on the rights of the “Locum Tenens” and his deputy.

The views professed in that statement cannot be reconciled with the material on the fate of Metropolitan Peter given by Protopresbyter M. Polsky in the second volume of his work “New Russian Martyrs” (Jordanville, 1957). On pp. 287-288, the author says that the term of exile of Metropolitan Peter was to be completed in 1935. The New York Russian Daily “Novoe Russkoye Slovo” (“New Russian Word”) announced that news had been received concerning the liberation and return of Metropolitan Peter from exile. The information was conveyed by the Russian Patriarchal Exarchate in America and was as follows: “We have been notified of the liberation of Metropolitan Peter; but until now this information has come only from Americans we know who have very recently returned from Moscow. They had seen both Metropolitan Sergei and Metropolitan Peter and talked to them. Later, about a month ago, a notice came from Moscow clerical circles with the following content: ‘We have news of the liberation of Metropolitan Peter. Metropolitan Peter Krutitsky was recalled from his exile six weeks ago and is now living in Kolomna. The health of the Patriarchal “Locum Tenens” is very unsatisfactory, especially his legs, which are suppurating from the colds he has suffered”.

A similar notice with one additional detail was published on April 3, 1937, in the Paris newspaper “Vozrozhdeniye” (“Renaissance”): “The term of exile was completed in 1935. Metropolitan Peter returned to Russia and met with Metropolitan Sergei. The latter wanted to obtain from him an acknowledgement of the new order of administration of the Church and his agreement to convene the Council. There was also other news, saying that the Bolsheviks had allegedly offered Metropolitan Peter the Patriarchal Throne, subject to certain conditions. Metropolitan Peter was adamant and refused to enter into any kind of compromise. Shortly after that he was once more sent into exile.”

The same notice was confirmed in the Paris paper “Russkaya Mysl” (“Russian Thinking”) of November 16, 1951. The above information was published with the addition of the following: “Metropolitan Peter demanded from Metropolitan Sergei that he hand over to him the function of “Locum Tenens”. This was refused him. Soon after that Metropolitan Peter was returned to exile, where he died at the beginning of 1937″.

These facts appearing in information later received from the USSR may serve to explain why Metropolitan Sergei kept silent about the reasons for his having assumed his new title.

Metropolitan Peter, having demonstrated his moral strength by refusing to enter into any compromises with the atheistic authorities, was eliminated by those authorities from the path of Metropolitan Sergei, who had shown himself willing to compromise. Yet the fact that he, Sergei retained the power in his hands, made it impossible to publicize the differences of views between him and Metropolitan Peter; nor could the latter’s death be announced publicly, nor the death of Metropolitan Arseny in 1936. That was rendered impossible because of the views earlier expressed by Metropolitan Sergei on the rights of the Deputy “Locum Tenens”. Inasmuch as Metropolitan Sergei agreed that the death of the “Locum Tenens” put an end to the exercise of the functions of his deputy, that death not only failed to clear the way for him to the assumption of power, but even deprived him of canonical status altogether. For that reason the Soviets kept silent about the death of Metropolitan Peter for some time. The Synod of Bishops took all possible steps in order to ascertain whether Metropolitan Peter was, in fact, dead. These steps included turning to diplomatic representatives and to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Office of the Archbishop of Canterbury informed Metropolitan Anastassy that it had received news from the British Charge d’Affairs in Moscow that an official memorial service was held for the late Metropolitan Peter in January, 1937, by the Dragomil Gates in Moscow. No notice of his death appeared in the Soviet press, however, until June, 1937.

About that time the news of Metropolitan Peter’s death appeared in many papers, although, in an official publication of the Moscow Diocese, “The Voice of the Lithuanian Orthodox Diocese”, published in Lithuania, mention of his death was made for the first time in issue No. 3-4, in April, 1937. The London Times of March 29, 1937, wrote that Metropolitan Eleuthery (in Kaunos), surprised and confused by the order of Metropolitan Sergei to have his name proclaimed as that of “Locum Tenens”, enquired of Moscow and received the following curt cablegram: ’’Metropolitan Peter is dead”. And yet in the statements printed in Metropolitan Eleuthery’s publication another riddle appears. On December 26, 1927, a decree was issued proclaiming Metropolitan Sergei’s name as that of Patriarchal ’’Locum Tenens”; but it was only as late as March 22, 1937, that a decree appeared in which it was stated that cognizance had been taken of the will of Metropolitan Peter dated December 5, 1926, and that in his will the following were designated as his successors: Metropolitan Cyril, Metropolitan Agathangel, Metropolitan Arseny and, in the last place — Metropolitan Sergei. It seems that the publication of the decree proclaiming Metropolitan Sergei’s name should have been preceded by the publication of that will, and not the other way round.

According to additional information received, the death of Metropolitan Peter took place on August 29, 1936, that is, more than half a year prior to the official publication of that death, and five months before the first memorial service was held at the Dragomil Gates.

Considering the general situation in the USSR, it is easy to imagine that the demise of Metropolitan Peter was not known and could not have been immediately verified by the church administration of Metropolitan Sergei. This may explain the delay in announcing his death. Nevertheless, memorial services for Metropolitan Peter ought to have been read not at the end of January but in December of the previous year had Metropolitan Sergei assumed the title of ’’Locum Tenens” in consequence of the demise of his predecessor. Owing to the fact that everything was done precisely in the reverse chronological order, it is impossible not to conclude that we have here a case of the usurpation of power carried out by Metropolitan Sergei with the acquiescence of the atheistic authorities.

Metropolitan Peter refused to conclude a bargain with the Soviet authorities. He entered the name of Metropolitan Sergei in his will in the fourth (last) place at a time when the latter had not yet embarked on a career of pandering to the authorities and making compromises with apostasy.

The will of Metropolitan Peter was written ten years before his death, at a time when he could not have foreseen that Metropolitan Sergei would deny all those principles for the sake of which he himself suffered arrest. Even if this were not the case, however, the bare fact that Metropolitan Sergei assumed the patriarchal diocese with the title of His Beatitude and the right to wear two panagias merely on his own volition while he was still Deputy “Locum Tenens”, constitutes an outrageously lawless act.

This lawless act, however, was to the profit of the Soviet authorities. They understood that the lengthy period during which the Russian Church remained headed by a Deputy “Locum Tenens” and the long term during which the patriarchal diocese remained orphaned were most clear indications that Church and religion were being persecuted. In order to create the impression abroad that the situation of the Church was, on the contrary, more or less normal, Metropolitan Sergei had to appear in the Church’s name not as Deputy “Locum Tenens” but as the acknowledged head of the Church, His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna. Besides these considerations, that title gave greater weight and stability to the personal position of Metropolitan Sergei.

Let us remember his own words — “that the powers vested in the Deputy “Locum Tenens” are valid only as long as the ‘Locum Tenens’ who had deputed him remains alive”. These words might easily have been remembered by Metropolitan Sergei when Metropolitan Peter’s death was imminent, but, wearing two panagias and bearing the splendid title of His Beatitude, the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna, Metropolitan Sergei seized the opportunity and, for his own purposes, made use of these obvious advantages over all the rest of the hierarchs, assuming the pose of natural successor to the primate. For a number of years his new title had cast his former modest title of Deputy “Locum Tenens” into the shadow. That leads us to assume that the above act was intended to enhance his authority abroad prior to his signing, two months later, a decree of interdict against the hierarchs abroad, in punishment for their refusal to give written promises and pledges of loyalty to the Soviet authorities. That decree, by the way, had no effect whatsoever, since not a single Eastern Church paid any attention to the Metropolitan’s illegal interdict.

All these things were done by Metropolitan Sergei at a time when all his accusers were already imprisoned. Therefore, the only body that could protest against Metropolitan Sergei’s anti-canonical usurpation of the title “His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna” was the free Russian Church Outside Russia. This was done without delay by Metropolitan Anthony. In his letter No. 4036 of August 7/20, 1934, addressed to Metropolitan Eleuthery, Metropolitan Anthony declared, in reply to Metropolitan Sergei’s letter No. 944 of July 22 of the same year, that his having proclaimed himself Metropolitan of Moscow during the lifetime of Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsk, constitutes an illegal usurpation of power by Metropolitan Sergei.

It should be noted that the canonical significance of this protest by the head of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia carries great weight, since it was issued by the hierarch of greatest seniority after the late Patriarch Tikhon. As Metropolitan of Kiev, Anthony was not only the senior hierarch of the Russian Church; he was also a permanent member of the All-Russian Synod. The fact that at that time he was living abroad owing to the persecution of the clergy by the atheists could in no way deprive him of his right to vote according to canon 37 of the Sixth Ecumenical Council.

Archbishop Anastassy of Kishinev and Khotin, another member of the All-Russian Synod, was in full agreement with that declaration of the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, and repeated his protest in the above-mentioned definition of the Synod of March 30/April 12, 1937. These acts underline and corroborate the canonical invalidity of the acts of Metropolitan Sergei whereby he took over the Moscow diocese and assumed for himself the title of “His Beatitude” at a time when he was still only Metropolitan of Nizhny-Novgorod.

III. Locum ‘Tenency’ Changed Into Patriarchal Incumbency

One lawless action draws another in its wake.

There is no doubt whatever that his change of title and the seizure of the Locum Tenency were but preliminary steps taken by Metropolitan Sergei with a view to gaining the title of patriarch. But the Bolsheviks were not at that time prepared to enhance the authority of Metropolitan Sergei to so great an extent. They were still hoping to crush the Church and to annihilate its root and branch. I have already mentioned that towards the beginning of World War II, not only had those who disagreed with Metropolitan Sergei been imprisoned, but even those who had collaborated with him. Diocesan administrations, in the re-installation of which he had taken such pride and concerning which he had boasted in his message of December 18/31, 1927, were in fact non-existent…

V.I. Alexeev, in his research work “Material for the History of the Russian Orthodox Church in the USSR” has written: “Dioceses, in the year 1941, did not exist as administrative bodies. There were only parishes which kept irregular contact with the Patriarchate. These parishes were, probably, very few. This may be concluded from the Pskov Mission and the fact that, in 1941, missionaries who arrived there from the Baltic States found only a single church that had not been closed. A similar situation existed in the South … In Kiev, when the Germans occupied it, there was only a single church, while in the Kievan diocese there were none. In 1943, however, close to forty churches were opened in Kiev and, in the Kievan diocese no less than five hundred.”

Stalin, having decided to use the Church as an instrument in his total war against the Germans, stopped the persecution and destruction of the Church, thereby reversing his former policy. To Metropolitan Sergei he even offered to restore the Patriarchate. It was, in fact, restored, but this was done in the same revolutionary manner as that in which Metropolitan Sergei had assumed the title of Metropolitan of Moscow. It cannot be emphasized too much that all this took place at the initiative of the enemies of the Church. The exceedingly straitened position of the Synod under Metropolitan Sergei could not for a moment permit it to imagine that he could have entree to Stalin. It could not be doubted, therefore, that the initiative for restoring the patriarchate came from Stalin himself. The measure was dictated by the internal situation of the U6SR and the areas under German occupation, where a strong revival of religious life was noticeable. It was also good propaganda, which would go a long way with the Western Allies. When Metropolitan Sergei was received by Stalin, therefore, the matter was given the widest possible publicity. The restoration of the patriarchate was pushed through at a speed such as can only be obtained when it is physically impossible for anyone to raise a voice of protest.

His reception by Stalin and his having previously assumed the title of Metropolitan of Moscow, were the decisive factors in the election of Metropolitan Sergei to the office of patriarch. Those bishops who disagreed with him had already been eliminated from his path by Stalin. In the eyes of the pro-Sergei party, Stalin suddenly became, instead of an anathematized atheist — ’‘the God-sent Leader”. Metropolitan Sergei’s only handicap remained the scarcity of bishops, but those could be brought back from exile to swell the ranks of the newly-consecrated ones. The first new dignitary was Pitirim, a former “Renovationist” priest who later became Metropolitan Pitirim Krutitsky.

The haste with which these measures were pushed through is obvious from the chronological data: on September 4, Stalin’s reception of Metropolitans Sergei, Alexei, and Nikolai took place; by September 8, the Council had already been convened.

It must be assumed that, considering Soviet bureaucracy on the one hand and the fear of Stalin on the other, the election of a patriarch had already been in preparation for quite some time before the three metropolitans were received by Stalin. The hierarchy was increased and its ranks filled out in view of the coming event. Even so, only 19 bishops were able to attend the Council.

The author of the most complete and best-documented book on this subject, the “History of the Russian Orthodox Church in Our Time” ( 3 vols., in German [2] Chrisostomos, Johannes, “Kirchengeneschichte Russlands der neuesten zit. ), Johannes Chrysostomos, compares the election of Patriarch Tikhon with that of Sergei. In the former case the names of candidates were openly announced; then, from the names of those which had received the most votes, one was chosen by drawing lots. In the case of Metropolitan Sergei, Metropolitan Alexei declared at the opening of the election that there was only one candidate and that, therefore, all the rules which normally apply to the election of a patriarch would be dispensed with. Chrysostomos draws the following conclusion from this: ’’When we compare this hasty formality of the election of a patriarch with that of the election of Patriarch Tikhon, which was a ceremony well-prepared in all its details, we cannot avoid the impression that the complete freedom which undoubtedly prevailed at the 1917 Council, was not to be found here even in the slightest degree. One cannot help asking why it was that the leaders of the Patriarchate were so afraid that they put forth only one candidate, and emphasized that fact so insistently and so tactlessly? …” Pointing out that among the eighteen bishops present there was not a single one who was representative of the opposition, the author asks: ”Why all that tension? Why that nervousness and those feverish efforts to prevent the possibility of a new discussion? and why the tendency to have a show of ’general enthusiasm and delight’ instead of a free exchange of opinions and the expression of freely-taken decisions?” This took place in Soviet Russia at a time when it had long ago become the accepted form to express “general enthusiasm” over anything that was suggested from ’’higher up”. Father Chrisostomos justly remarks that the leaders of the Patriarchate were in deadly terror of the possibility that someone might name another candidate when they had already received their instructions from Stalin that Metropolitan Sergei was to be elected. It was a futile gesture when the Archbishop of Saratov, Gregory, after his welcoming address following the enthronization, found it necessary to castigate the ’’opposition”.

Thus a thorough study of all the circumstances leading to the election of Metropolitan Sergei as patriarch has convinced us of the fact that he achieved his purpose by eliminating from his path all those bishops who were not prepared to swear allegiance to the atheistic Government. Many of them were still alive and languishing in prisons. He was elected patriarch in haste, by a council composed of only a small number of bishops, hand-picked and conveyed to Moscow especially for that purpose. At the time, there were many more Russian bishops both in the areas occupied by the Germans and also abroad, who were prevented from participating in the election of the patriarch. This election contains every element that would constitute an infringement of canon 30 of the Holy Apostle’s and canon 3 of the Seventh Ecumenical Council. The latter canon contains the sternest condemnation of Metropolitan Sergei: ”If any bishop making use of the secular powers shall, by their means, obtain jurisdiction over any Church, he shall be deposed, and also excommunicated, together with all those who remain in communion with him”.

The famous interpreter of canon law, Bishop Nikodim Milash, gives the following explanation of the 30th Apostolic Canon. “If the Church condemned the illegal interference of the secular powers in the appointment of a bishop at a time when the rulers were Christians, how much more severely must she condemn it when the rulers are pagan; and an even heavier punishment must be meted out to those who are not ashamed to turn to pagan rulers and the authorities subordinate to them in order to obtain episcopal power and rank. This canon ( the 30th) provides precisely for such cases”.

Why is it that the Church so severely condemns a bishop who has obtained his position with the help of the secular authorities? Because such an action gives reason to suspect that the bishop is motivated by considerations which lie outside the sphere of the Church’s interests; and also because a bishop who has reached his position thusly, and who owes his election not to bishops but to persons pursuing their own interests and inimical to the Church, is doubtless compelled to serve “two masters”. (Matthew 6:24). To such a bishop, these words of our Savior apply: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, he that entereth not by the door into the sheepfold, but climbeth up some other way, the same is a thief and a robber” (John 10:1).

Seeing that the Church so sternly condemned the obtaining of episcopal office with the help of secular powers which were not hostile to the Christian Church and were not persecuting her, what can be said of the occupation of an episcopal chair with the help of an authority that has made it its purpose to exterminate all religions?

Could it be said that a patriarch nominated with the help of Antichrist will have a canonical right to his power? We do not suppose that anybody will venture to give an affirmative answer to that question. And yet the Soviet authorities openly declare themselves to be atheistic, and their power is one of apostasy, i.e., is of the same nature as the power of Antichrist. It follows from this that Sergei, who was nominated by that power, was not a patriarch but a pseudo-patriarch.

IV. The Patriarchal election in 1945

A successor to Sergei was appointed beforehand in the person of the Metropolitan of Leningrad. Alexei. That much is clear from the letter of Metropolitan (later Patriarch) Alexei which he addressed to Stalin after the death of Patriarch Sergei. In that letter he speaks of having received three metropolitans, of his predecessor’s loyalty to Stalin, and explains the principles of his own future activities: “By adherence to canon law on the one hand and unfailing loyalty to the Motherland and the Government that is headed by you on the other hand, by acting in full agreement with the Council for Russian Church Affairs and in conjunction with the Holy Synod established by the late Patriarch, I shall be able to avoid making mistakes and taking wrong steps”.

It would not seem that a “Locum Tenens”, whose only task is to prepare for the speediest possible election of a patriarch, need have given this kind of assurance. The letter may be interpreted as a promise of obedience and submission on the part of a person already “indicated” by Stalin as the future patriarch, a declaration that he intends to follow the example of his predecessor in the latter’s obedience to the authorities.

Turning to the election of Metropolitan Alexei as Patriarch, it is impossible not to see signs indicating that his election also was decided beforehand “from higher up”. When the All-Russian Council was electing a patriarch in 1917-1918, it had full freedom of choice. Three candidates were chosen by vote, and the election was completed by drawing lots between those three. The election of Metropolitan Alexei to the patriarchal office, however, proceed-along different lines. The first meeting of the Council took place on 31 January, 1945. There were two subjects on the agenda: the election of a patriarch and the confirmation (not the working out) of a “Statute of Administration of the Russian Orthodox Church”, which was to replace the statute that had been worked out as a result of numerous meetings and after thorough discussions during free debates at the All-Russian Council in 1917-18.

The Council of 1945, however, met only twice. The first meeting, was to a great extent, devoted to the solemn reception of important foreign guests invited to attend. After the greetings and welcoming speeches, a report was given by the “Locum Tenens” “on the patriotic activities of the Church during the war”. It was only after the reading of that political report and the voting of a resolution upon it that the draft of the “Statute of Administration of the Russian Orthodox Church” was heard. This important document did not provoke a single objection — “so thoroughly was it prepared as far as both its canonical basis and its practical details were concerned”. (Patriarch Sergei and his “Spiritual Inheritance”, p. 324, Publ. by the Moscow Patriarchate, 1947).

Everybody knows, even a person with scarcely any experience in the conduct of public meetings and the submitting of drafts for legislation, that in a free atmosphere such drafts, no matter how thoroughly they may be prepared, always draw certain objections, require changes or modifications, corrections, etc. Only the particular conditions existing in the USSR allowed such an important document, and one which is far from being uncontroversial, to be approved and accepted without encountering any objections. This statute has been seriously criticized by Prof. Kolesnikov in the publication of the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, “Church Life”. The criticism appeared in an article called “An Analysis of the Statute of Administration of the Russian Orthodox Church”, which appeared in the above publication on January 31, 1954.

An even stronger impression of fraud in the case of that Council — the participants in which were completely deprived of free choice — is given by the so-called “election” of the Patriarch, which took place the next day. The election was carried out by open vote and was, of course, unanimous. In the description of the Council cited above there is an interesting detail: “Thus the election of Patriarch Alexei, took place, confirmed by a special Writ then and there handed to the Electee” (ibid p. 326). From this it may be inferred that the election had been decided beforehand to such an extent that even the Writ “happened” to be prepared in advance.

The participation of the Soviet authorities in the organization of the Council is clearly confirmed in the article written by Metropolitan Nikolai entitled “At the Reception by Stalin”. This article says that Patriarch Alexei thanked the Government for “arranging transportation for the arrival of the invited guests from abroad and providing them with warm clothing during their stay in our wintry country, lodgings and food for all the members of the Council, and cars and buses for moving around Moscow” (Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, 1945, №5, pp. 25-26).

When authorities who publicly declare that they aim at the destruction of religion organize, in such a remarkable manner, the material side of a Council for the election of a patriarch, is it possible to doubt that these authorities were doing anything but pursuing their own aims, aims which they intended to achieve through the Council and which have no connection with the interests of the Church? It should be remembered that government assistance was given not only for the reception and upkeep of the foreign guests, but that all the members of the Council were kept in Moscow at Government expense as well. It must also be remembered that Government funds were spent on the election to the office of patriarch of a candidate favored by atheists.

If one judges these events objectively, it is impossible to accept a council of this sort — one which was set up by the Soviets — as canonically legal, nor can one accept the election of a patriarch staged by them as canonical.

The Soviet authorities’ interest in having the Church headed by a docile patriarch was perfectly clear from the very beginning, when all the opponents of Metropolitan Sergei were eliminated beforehand in order that his way to the Patriarchal Throne might be unimpeded. The elimination of those who were “personae non gratae” to the Soviets was effected by accusing them of some crime or other. Charges were easily found against anyone considered undesirable by the authorities. Khrushchev himself said, in his famous speech at the closed session of the Convention of the Communist Party of the USSR, that, “during the many trumped up trials” the defendants were accused of “preparing acts of terrorism” (Speech of Khrushchev at the closed session of the Convention of the Communist Party of the USSR. Munich, 1956, p. 17). Khrushchev was referring mainly to the victims of the Stalinist terror, who were Bolsheviks. Speaking of the arrest of 1108 out of 1956 delegates at the Seventeenth Convention of that party, he said: “That fact alone, as we see it now, demonstrates the absurdity and irrationality of those fantastic accusations of counterrevolutionary activities made against the majority of the participants in the Seventeenth Party Convention” (ibid, p. 16).

When even influential party members were not safe from unjustified persecution on fictitious grounds, what can be said of defenseless ecclesiastics? A close collaborator of Patriarch Sergei, his Exarch in the Baltic States during World War II, in a paper about the situation of religion in the USSR, said that the final and decisive word in the appointment of clergy remains completely dependent upon and at the arbitrary mercies of the Bolsheviks, who permit some to perform legal Divine Services while they eliminate others, naturally preferring the worst to the best.”

Repeating the words of S.V. Troitsky already quoted above, that “The possession of a right does not depend upon its exercise, but the exercise of a right depends upon its possession”, we are bound to conclude that the election to the Patriarchate of Metropolitan Sergei and also of his successor, has no canonical force.

The comparatively large number of bishops who were present at the election of the latter, and the presence of representatives of other local Eastern Churches, cannot change anything in that respect. The representatives of other local Orthodox Churches, being present only as invited guests, took no part in the election of Metropolitan Alexei to the office of patriarch. Moreover, they were poorly and one-sidedly informed about the situation of the Church in the USSR and were thus misled. How could they know that a large number of the gray-haired and gray-bearded bishops participating in that Council were just newly created? How could they know by what criteria clerics and laymen had been drummed together, and whether they arrived at the Council as a result of free elections according to the rules established at the All-Russian Church Council in 1918? They certainly could not have known that all those people were brought to Moscow for the sole purpose of “voting unanimously” — according to the Soviet custom — for the candidate who had been named to them in advance, and that the casting of votes had to be done in the presence of the heads of other Churches.

No matter what authority these silent witnesses of that illegal act possess, their presence at the performance of that act does not make it legal.

It is impossible not to mention once more, the fact that the great majority of the bishops who elected Metropolitan Alexei to the position of Patriarch were consecrated after 1943. The canonicity of these bishops depends on the canonicity of the authorities who gave them their rank — and, as has already been pointed out, the power of Metropolitan Sergei, who later became patriarch, was not canonical. No matter how many bishops were made by him and his successor, they may not be conceded to be any more legitimate than those who were the source of their power.

This is the formal side of the question. Of even greater importance, however, is the heart of the matter — the treason to the principles of Orthodoxy as described above, and the fact that such treason deprives all acts of the present-day Moscow Patriarchate of any canonical validity, thus rendering them void of any moral force and therefore not binding upon its flock. Supporters of the Moscow Patriarchate are fond of quoting canon 14 of the First-and-Second Council of Constantinople (A.D. 861) when they demand obedience to Moscow from all Russians, including those bishops who reside abroad. But this canon, like canon 13 of the same Council, merely establishes that normal canonical obedience is to be given to the representatives of Church authority as long as they have not been exposed or indicted by a Court. However, canon 15 of the First-and-Second Council provides a corollary to the above canons and to canon 31 of the Holy Apostles. It explains that interdict is imposed on those who refuse obedience to their church authority without valid reason i.e., those who, using certain accusations as a mere pretext, cease to recognize the authority of their spiritual leaders, “create schism, and destroy the unity of the Church”. On the other hand, it is ruled that those who shall separate themselves from their leaders before a Council on the grounds that there has been real treason to Orthodoxy, not only are not liable to punishment as laid down in the canons, but are “worthy to enjoy the honor which befits them among Orthodox believers”.

Those are precisely the grounds which many believers had for breaking off communion with Metropolitan Sergei, believers inside Russia as well as our hierarchy abroad. Therefore, to apply the canons of the First-and-Second Council to them is futile. It should be added that after the acts of Metropolitan Sergei had been marked as flagrantly treasonable to the Orthodox Faith, and his election and that of his successor shown to be un-canonical, any acts of theirs directed against the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia could have no moral force whatsoever.

V. Preliminaries to the Election of the New Patriarch

The closing of more than half of all the churches in the USSR during the intensified assault on religion upon Khrushchev’s coming to power, evoked a series of protests from the religious segment of the population, news of which reached the free world when more flexible lines of communication were revived and travel from the West made easier. Thus, a series of documents reached us, which vividly pictured the enslavement of the Church by the atheistic authorities.

These documents show how justified the elder Russian bishops were in denouncing the fallacies of the Church policies implemented by Metropolitan Sergei from the time of his notorious 1927 declaration. The difference between the new denunciators and the former ones who repudiated the declaration immediately upon its promulgation, lies in that the present day dissenters, despite their opposition to and well-founded disagreement with those policies, maintain the hope of compelling the Soviet authorities to minimize their interference in Church affairs by a firm stand of the hierarchy, grounded on Soviet Law. However, this hope is unrealistic since it neglects the Communist antagonism to any religion and its aim to destroy it as a matter of principle. Those who entertain such hopes regarded it especially important that the Patriarch, as head of the Church, should be a leader and not a willing tool in the hands of the atheistic authorities.

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia is not alone in pointing out the deviation of the Moscow Patriarchate from canonical laws and from the path of truth, for there are also many zealous, alert and sincere believers in the USSR, even among those who continue to officially belong to the Patriarchate while disagreeing with its policies.

In this respect it is interesting to note the views voiced by Archbishop Germogen (Golubeff) of Kaluga, and two Moscow priests, Nikolai Eshliman and Gleb Yakunin.

Archbishop Germogen is one of the most erudite theologians among the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church. In addition, he is undoubtedly the most courageous of all the bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate. In his function as a diocesan bishop, he tried to oppose the pressure of civil authorities, assiduously and bravely protesting the closing down of churches. He was successful, up to a point, until he was deprived of his diocese, at the insistence of the civil authorities.

In 1961, a council was hastily convened at the command of the atheistic authorities, to change the standing statutes of the Russian Orthodox Church (obviously in violation of all canonical laws). On the initiative of Archbishop Germogen, eight bishops sent notes protesting this change. Under pressure from the Government, seven bishops retracted their protest.

Archbishop Germogen alone did not give in to Government demands; it was this stand which led to his being deprived of his See. As the priests Nikolai Eshliman and Gleb Yakunin wrote in the supplement to their report to the Patriarch, which they sent to all the bishops, “Archbishop Germogen was given to understand that the decision of the Patriarch (concerning his dismissal from his See) was engendered by the urgent demand of the leaders of the Governmental Council (of Affairs of the Russian Church) who used, for this end, the alleged insistent complaints on the part of the Chairman of the Regional Executive Commissariat.”

Although he protested against the anti-canonical action in the Moscow Patriarchate, Archbishop Germogen did not join the ranks of those uncompromising foes to Metropolitan Sergei’s agreement with the Soviet rulers, such as Metropolitans Peter, Cyril, Joseph and others. His point of view has been that the spiritual integrity of the Church can best be defended from a position based on the sure ground of existing laws. His stand is given both in his statement to Patriarch Alexei and in his paper on historical-canonical and juridical material, distributed in 1968 for the 50th anniversary of the restoration of the Patriarchate in Russia. It was published abroad in the “Messenger of the Russian Christian Student Movement”, №86, 1967.

The weak side of this view point lies in its being based on the premise that the possibility exists of a long term non-interference on the part of Communist civil authorities in Church affairs, thereby completely ignoring the Communist Party’s goal of the total destruction of religion. This is not unlike nurturing hope that a modus-vivendi can be established between a wolf and a lamb which has been caught in its paws.

Nevertheless, Archbishop Germogen’s view-points are certainly important. He compares the present Moscow Synod with the Synod composed according to the precepts worked out at the All-Russian Council in 1917-1918. The Synod, properly structured, according to his words, “would have been authoritative and a representative body of the Highest Church Administration within our Church, having the canonical and moral rights to speak for the entire Russian Orthodox Church.” In contrast, referring to the present Synod in Moscow, Archbishop Germogen writes: “This cannot be said of our present Synod based on the grounds of the Statutes for the Administration of the Russian Orthodox Church” accepted at the Council of 1945. Nothing is actually said in these Statutes about the structure of the Synod, stating only that it consists of six members. Furthermore, Archbishop Germogen points out the non-canonical participation of civil authorities in its organization. In his words, “the permanent membership of the Synod, as well as the bishops’ appointments, transfers and dismissals, at the present time depend on the Chairman of the Council on Religious Affairs, to a much greater degree than they depended in Tsarist Russia on the Over-Procurator of the Synod (p. 74).” As an example of those who, because of this dependency are named to high offices, he mentions the appointment of Bishop Ioasaph of Vinitza as Metropolitan of Kiev and as a permanent member of the Synod.

“Prior to his consecration as bishop, he was thrice ordained a priest. The first time in the Renovation schism, the second time under Hitler’s occupation of the Ukraine, by Bishop Gennady in the jurisdiction of Bishop Policarp Sikorsky, and a third time by the Archbishop of Dniepropetrovsk, Andrei (Komarov).

Having been consecrated Bishop of Soumy, he promoted the closing down of that diocese. Transferred thereafter to the See of Dniepropetrovsk and Zaporozhye, he took over a diocese with 268 active parishes. In a very short time of his tenure that number was reduced to less than 40 parishes. He was then tranferred to the Vinitza See where in a short time the Cathedral of that see was itself shut down (p. 74)”.

Archbishop Germogen notes that the possibility of such appointments bears witness to “grave irregularities in the structure of our Synod”, (ibid). He further observes that the statutes of 1945 were not preceded by a resolution regarding the repeal of the statutes laid down in 1917-1918, by a Council of equal significance.

“If the Conference of Bishops which took place in the autumn of 1944 on the question of preparing for the election of a patriarch at the Council of 1945, changed the order for the election of a patriarch set down by the All-Russian Council of 1917-1918, it violated the established canonical order according to which a greater Council corrects the decisions of the lesser one, and not vice versa. Therefore, like decisions have no validity for the future election of a Patriarch.” (p. 77)

Speaking of the 1945 statutes, Archbishop Germogen clearly hinted that it was imposed upon the Church by the civil authorities: “Studying the Statutes one clearly feels that they were not worked out by the Council, but were presented to the Council in completed form merely for affirmation; while canonical order in the conduct of business in the Council demands mandatory discussion of problems subject to settlement. Without the proper and thorough discussion of each matter placed before it, the Council loses its meaning” (p. 75). Therefore, in the opinion of Archbishop Germogen, the election of the patriarch in 1945 was conducted illegally. From this it follows that any new elections, which would be conducted in a similar manner, would also have to be considered in violation of the law. Without doubt, his desire to forewarn of this lay behind his reason for compiling the memorandum he prepared for the 50th anniversary of the All-Russian Church Council of 1917-1918, and so he furnishes a detailed account of the order of procedure in the election of the patriarch, established at that Council.

Archbishop Germogen reminds us that the legitimate procedure for the election of a patriarch is as follows:

- The patriarch is elected by the Council, which consists of bishops, clergy and laymen.

- Voting is by secret ballot.

- All members of the Council participate in the voting — bishops, clergy and laymen.

“The Council, convened to elect a patriarch, holds three meetings. At the first meeting the candidates for patriarch are nominated. Every member of the Council has the right to nominate a candidate. In order to name a candidate to the patriarchal throne, every member of the Council writes one name on a special ballot and presents it to the Chairman of the Council in a sealed envelope. The Chairman of the Council announces the names written on the ballots and compiles a list of these, with a tallying of the votes for each candidate.

“At the second meeting, the entire Council chooses three candidates from the announced list by secret ballot, writing three names on the ballot. Of the chosen, three are acknowledged, each of whom must have received not less than one half of all the votes, and the largest number of votes in comparison to the others subject to the voting.

“If, at the first balloting, no one is elected, or less than three are elected, another balloting takes place, at which time the voting lists are proffered with the designation of three, two or one name, in accordance with the number remaining to be elected.

“The names of the three chosen candidates are entered, in the order of the number of votes received, in special Council minutes.

“In the event of a unanimous election of a candidate to the Patriarchate, the balloting for two other candidates does not take place.

“At the third meeting, which takes place at the Patriarchal Electoral Cathedral, the patriarch is picked by drawing a name from the three designated candidates listed in the Council document, while in the event of an unanimous election of a patriarch, the name of the elected patriarch is announced”, (p. 76).

A retort can be made to Archbishop Germogen that the election of Patriarch Alexei was unanimous. However, it must not be forgotten that, in the eyes of the electors, Metropolitan Alexei was already a candidate of the Government. To openly vote against him was unsafe for anyone. But that does not preclude the fact that with secret balloting, another candidate may well have been put forth. This opportunity was not given to the members of the Council. Under Soviet conditions no one could dare to openly speak for the inclusion in the candidates’ listing, of another name, since it was perfectly clear to everyone that, from the viewpoint of the Government, there should be no candidates other than the one previously approved by the Government.

The question of procedure in the election of the patriarch is also given consideration in the well known open letter to Patriarch Alexei from two priests Father Nikolai Eshliman and Gleb Yakunin, which was written in 1965 and received widespread circulation outside of Russia.

This letter was undoubtedly written under the influence of Archbishop Germogen.

The above-named priests pointed out that from the time of Metropolitan Sergei’s pronouncement in 1927, the Patriarchal Administraton deviated from the path on which it was directed by Patriarch Tikhon — “the inadmissibility of interference by lay functionaries in the spiritual life of the Church on the one hand, and strict observance by Church leaders to civil laws on the other hand, — this is the fundamental principle of the civil existence of the Church, which the Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon, true conveyer of the thinking of the whole Church, bequeathed to his followers. However, the history of the Russian Church during the past 40 years bears indisputable witness to the fact that, beginning from the time of the lengthy Locum Tenency of Metropolitan Sergei (Starogorodsky), the highest Church administration ignored the patriarchal legacy and, arbitrarily changing course, went along the path of deliberately liquidating the Church’s freedom.

These two priests give many factual examples to corroborate this conclusion: “The Council on the Affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church”, they write, “radically transformed its character, changing from an official intermediary agency into an agency of unofficial and illegal administration of the Moscow Patriarchate”.

“Currently in the Russian Church, a situation has been created in which not one aspect of church life is free from administrative interference on the part of the Soviet Council on the Affairs of the Russian Church, its delegates, and local organs of power; interference directed at the destruction of the Church, telephone directives, oral instructions, unrecorded unofficial agreements. This is the atmosphere of unhealthy secretiveness which has enveloped the relationship of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Soviet Council on the affairs of the Russian Orthodox Church in a thick fog.” (p. 5).

It is appropriate at this point to remember the characteristic method of this unofficial submission to the atheistic government officials in Church matters, which is cited in the February 20, 1968 letter of Archbishop Germogen addressed to Patriarch Alexei. He relates a conversation he had with the late, former member of the Synod, Metropolitan Pitirim of Krutitsky: “Once, meeting me at the Patriarchate”, writes Archbishop Germogen, “and discovering that I was having difficulties with the Commissioner of Tashkent, he offered this advice: ‘To avoid all complications, do this: when a priest or a member of a parish council comes to call on you concerning any Church matter, listen to him, then direct him to see the Commissioner and to report to you again afterwards, so that having been seen by the Commissioner, he would return to you. When he returns and is announced, you telephone the Commissioner and ask what he told your caller. And then you tell him the same thing that the Commissioner told him’.”

In that way, decisions concerning Church matters are given through the mouth of the bishop, but in reality come from an atheist, an enemy of the Church. This is a fallacious principle, which lies at the foundation of all the administration and all the decisions of the Moscow Patriarchate.

The above mentioned two Moscow priests do not particularly analyze the question of procedure in the election of the Patriarch, which point is debated by Archbishop Germogen. Still, having described in detail the various forms of total enslavement of the Church administration by atheistic powers, they seek a solution in the convocation of a free Council, which would truly express the voice of the Russian Church.

“The assembling of a Local Council in the near future”, they write, “is dictated by the urgent need of an overall Church judgment as to the activities of the Church Administration and the urgent need for an early decision concerning historically ripe problems of Church life and of Church teachings.

“In order that the new Local Council would not find itself an obedient instrument in the hands of non-church powers, it is essential that the entire Russian Church actively participate in preparing for this Council. There must be parish meetings and gatherings within the dioceses. Only then can the Council be attended by clergy and laymen, truly representing, together with the best bishops of the Russian Church, the fullness of the consensus of the Church.”