From the Editor

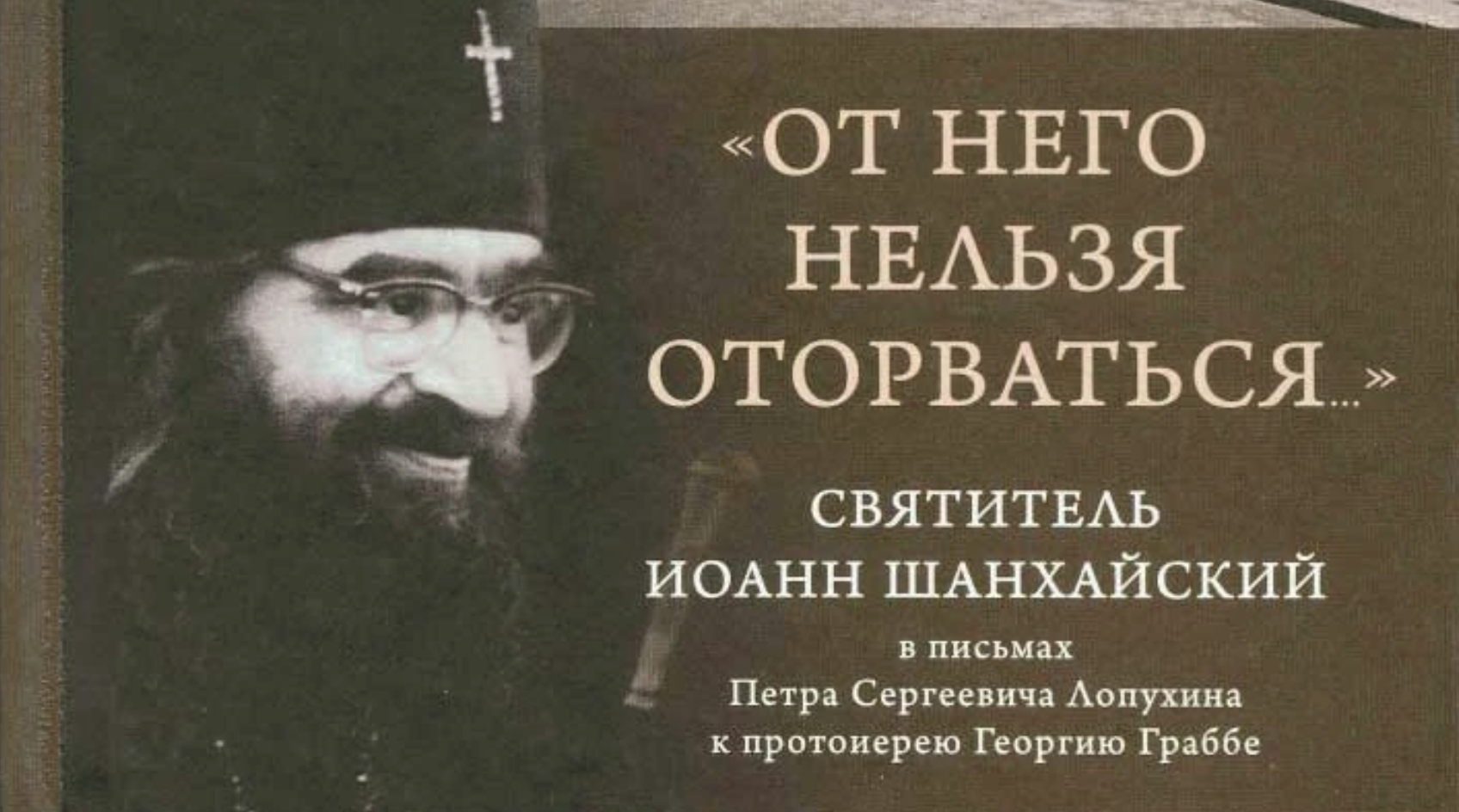

When the ROCOR was informed in 1937 of the death of the Patriarchal locum tenens Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy, it changed the formula of commemoration of the church hierarchy at litanies (where today the Patriarch of Moscow is commemorated) to the “Orthodox episcopacy of the persecuted Russian Church.”Beginning with Metropolitan Sergius in 1943 and ending with Patriarch Alexis II in 1990, the ROCOR refused to recognize.ze the elections of the Patriarchs of Moscow as being canonical. This led to the ROCOR considering the “hidden Church” within Russia, which likewise did not recognize the Moscow Patriarchate hierarchs as canonical, as its mother church. This conviction was formally expressed in a 1971 resolution of the ROCOR Council of Bishops in response to the North American Archdiocese receiving autocephaly from the Russian Orthodox Church. This interview with Father Oleg is valuable for its in-depth factual analysis of the problems that confessors of Orthodoxy, and those who have tried to emulate them, have faced along the way. There is only one ROCOR, now a self-governing part of the Russian Orthodox Church. That said, I cannot accept the view that our church was “cleansed” of those who left it in 2001 and 2007. Those who broke away were brought up during the Cold War years in a spirit of confrontation that does not leave room for dialogue. Is it possible that Father Oleg could be our voice to those who have left us? Our hand may well remain outstretched, but to extend it would be worthy of our Church of the Metropolitans: Antonii, Anastasii, Laurus, and Hilarion.

Protodeacon Andrei Psarev

July 23, 2022

We are talking today to Archpriest Oleg Mironov, rector of the Church of St. Xenia of Petersburg in suburban Ottawa. Father Oleg, I am very glad things worked out so that we could have this conversation. Could describe how you came to Christianity?

You know, I was a late convert to the faith, in the 1980s and early 1990s, when people in Russia started to return to their roots after the millennial celebrations of the Baptism of Rusʹ, when monasteries were being restored everywhere. My personal journey was quite complicated. I was baptized Orthodox not through any decision of my own, but rather owing to the desire of my relatives. I was about 12 years old and already an entrenched atheist at the time, and I was very worried about it. It was a matter of seeing my freedom of choice violated, of having the sacrament performed on me without my inner consent. Naturally, I continued to pursue a way of life quite distant from religion.

The initial impetus for me was being conscripted into the Soviet army, since students in the 1980s were drafted into the Soviet army, and after my second year as a physics student, I wound up in a fairly difficult atmosphere. I think the primary thing for me was not even the knowledge of God, of faith, but the knowledge of the “underside.” That is, I first understood that there is an underworld. Then I learned, by analogy, that there must be some alternative to all that. When I came back after compulsory military service, I began to think about changing my occupation. That is, at first, I thought about going to study philosophy at Moscow University, but on second thought, I decided to finish my studies. I got my degree in physics and was assigned to a job. But in my final years at university, I began to lead a fairly active church life. That was 1990/91. I went to monasteries and was present at the reopening of Valaam Monastery, the skete at Optina Hermitage. I saw Zadonsk Monastery being restored before my eyes.

And so it happened that after graduating from university and working for a couple of months as a design engineer at a third-tier radio technology research facility in Voronezh, I decided to enter a theological seminary. At that time, Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Institute was accepting applications, and my father-confessor, the now-retired Metropolitan Nikon of Zadonsk, gave his blessing for me to apply and study there, at the Faculty of Theology and Pastoral Training. So I did, while I working in tandem at the Moscow Patriarchate publishing department in Danilov Monastery, then on Pogodinskaia Street. The mission of the Orthodox Church in America was located there at the time. A certain Thomas Bates was there, who wrote a book about Rasputin that was published by the Brotherhood of St. Herman of Alaska. I met all kinds of people who later influenced my life’s journey, too – James Paffhausen, who later became metropolitan of the Orthodox Church in America. He and I were on very good terms for a long time during my studies, traveling together, traveling to Russia, to monasteries.

In 1994, I began working for the Voronezh Diocese office. I was the head of the diocese’s publishing department; we published a newspaper and a magazine. Naturally, in parallel, I was reading a lot and learning about the history of the Church Abroad. I was beginning to think about a ROCOR parish early on in my church life in 1991, when they were opening parishes in Russia, in Suzdal and elsewhere. But since all my friends and contacts were in the Moscow Patriarchate, I stayed where I was for the time being – which was a very difficult time in economic, material, and spiritual terms. The 1990s were difficult times in Russia. For example, we had to get paper for the diocesan magazine by hook or by crook. Probably out of frustration with such practices, I came back to my decision to join the ROCOR.

I graduated and, after that Vladyka Laurus, after a conversation with our Mother Margarita, invited me to Jordanville for possible ordination. I did not think I would be ordained to the priesthood.

At the time, Voronezh had a famous catacomb parish led by Abbess Margarita (Chebotareva). Matushka Margarita was a very famous catacomb confessor and had been tonsured by the Voronezh new martyr Archbishop Peter Zverev. I began to go to her parish without any plans to pursue a church career. At that time, I was also a graduate student at the Faculty of Philosophy in Voronezh, and I saw myself as more in academia than in priestly ministry. At this time, however, a very interesting situation took shape in Voronezh. Archbishop Laurus was one of the few foreign bishops who took a real interest in the life of the ROCOR parishes in Russia. I traveled around with him later, after I had became a priest (and some time before that), visiting a lot of parishes. That is, he really had his finger on the pulse of church life. He wanted, it seems to me now, to understand how benign everything was in church terms and how much he could rely on it. I may be wrong, but at least his interest in the catacomb church in Russia was quite evident. He took an interest even in the smallest congregations; for example, he would drive 3,000 kilometers in some old rattling Soviet banger of a car just to see, for example, a catacomb congregation in Krasnodar, Kharkov, or elsewhere. At the time, I had a fairly busy schedule in terms of my studies, and I had no plans to graduate from the theological institute. However, Vladyka Laurus insisted that I get the degree and not put “all my eggs in one basket.” That I should not only study the methodology of science, as I was doing by studying at the Department of Ontology and the Theory of Knowledge, but also continue to study long-distance at Saint Tikhon’s. I graduated and, after that Vladyka Laurus, after a conversation with our Mother Margarita, invited me to Jordanville for possible ordination. I did not think I would be ordained to the priesthood. Frankly, I hoped that I might be able to remain a deacon and continue teaching. I did not think at that time that I would be able to do both. That is, to serve as a priest and at the same time teach at my university in Voronezh.

And there was more to it than that. At that time, a metochion of the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville was being built in in Istra. In Voronezh, we commemorated three bishops at that time: Metropolitan Vitalii, Archbishop Laurus, and Archbishop Lazar (Zhurbenko). I don’t even know what the status of this parish was. In my opinion, it was something similar to stauropegial. Hieromonk Evfimii (Trofimov) was serving there. He was ordained by Bishop Lazar and served with his permission in Archbishop Laurus’ parish.

When Archbishop Laurus ordained me, it was a kind of exchange. I stayed in Voronezh in order to serve at the parish where Father Evfimii from Moscow had been serving earlier. Father Evfimii could focus entirely on building up the metochion, even though he remained our rector and served in Voronezh almost every Sunday. In other words, I may have conducted a few services there on my own over the years, but he and I served together. Nevertheless, my ordination relieved him of some of his pastoral duties. He could send me, for example, to serve at other parishes. We could help each other. And that was important, because in some regions we had several thousand parishioners. For example, Chuvashia, we received literally thousands of letters of confession on feast-days. We then had to read them at a certain hour and say a prayer of absolution over them. And these people, who still retained the holy gifts from the catacomb priests there, were able to receive communion. They were in various regions: Volgograd Oblast, Novomoskovsk, Chuvashia.

There’s just one thing I want to clear up. As I see it, Vladyka Laurus is now presented as if he were basically born with a mission to re-unite the churches. What I see is that he was a man of the church. He didn’t want us to have parishes in Russia. But as soon as there were some, he got fully involved. As a boy during the war, he was impressed by a meeting with catacomb Christians from the USSR who told him about Archbishop Zakharii. There was a publication about him in Orthodox Russia. That is, he had heard about all this from a young age, met with them. He understood what was happening. These people were comprehensible for him.

I absolutely agree, because I got the impression from many conversations with him and from his travels that Bishop Laurus had developed some frustration with the Catacomb Church in Russia. And it had some basis in fact.

The answer was the Istra metochion. Seeing all this, he wanted to create a place that was free of conflict. I remember traveling around our parishes in Russia in the summer of ’96. The people were clearly isolated, and so on. But there were conversations and discussions of sorts everywhere – a certain intensity of goings-on, and what he wanted was constructive activity. That was his vision for the metochion.

I think that was the case. And naturally, Archbishop Laurus had better knowledge than anyone, shall we say, of the strengths of the catacomb movement in Russia, and its weaknesses. There really were holy people in it. There were so many interesting and, you might say, ardently believing Christians. But this movement, of course, eventually brought people such as Archbishop Lazar (Zhurbenko) to the fore. This late-Soviet catacomb environment was very difficult. Mother Margarita herself also knew and saw a lot about it. She held fast to the Church Abroad as long as possible, as long as it was possible, not to sink back into the muddle of some quarrels and mutual accusations.

Father Oleg, Olga Vladimirovna Kosik of the Saint Tikhon’s Theological Institute has published letters written by Father Iosif Zhurbenko (the future Archbishop Lazar) to Holy Confessor Athanasius (Sakharov) in the 1950s. There is a feeling of “we are the last, no one needs this church in modern Russia anymore, it’s all dying, coming to naught.” That’s the kind of despair I sense in these letters from the future Vladyka Lazar. So when this catacomb movement surfaced, it seemed that leading it would not be for him. But you talking about thousands of people, that’s an altogether different scale.

Yes, possibly. Moreover, I can tell you that all the real catacomb leaders, such as Shura Shevchenko from Kharkiv, Matushka Margarita, and the nuns from Novomoskovsk – they all had pent-up negativity toward the ROCOR leadership in Russia and toward Vladyka Lazar and Vladyka Veniamin. As they themselves said, if they had not been bishops of the Church Abroad, then knowing their background and because they knew them as they moved up, they would never have thrown in their lot with them…

So what you’re saying is that the Church Abroad lent a certain kind of solidity, stability. That’s why they intuitively held on to it?

Of course: it was an anchor, a real anchor. You see, say, in the parish where I served until 2009, another catacomb parish was later created. One of our nuns, mother Aleksandra (Gubareva), was the cell-servant of Father Mikhail Rozhdestvenskii, and she was also on good terms with Father Nikita Lekhan. They were sure that Vladyka Lazar was a government agent. Mother Aleksandra told me, for example, the consecration of how Vladyka Lazar was consecrated. She had personally gone to St. Petersburg to speak with Father Mikhail Rozhdestvenskii. By the way, Shura Shevchenko also confirmed this. A very interesting story. when Mother Aleksandra was taking the future Vladyka Lazar to meet with Father Mikhail Rozhdestvenskii, he just ran out of the train right in front of her in Rostov-on-Don. Didn’t go any further. Then he said there was a raid and he had to escape under the train cars. There was a whole story as to why he did not want to come to meet Father Mikhail. All in all, these mutual resentments had been building up over the decades. The legal status that the Church Abroad gave the Catacomb Church in Russia after the consecration of Bishop Lazar in 1992 was a very powerful factor in consolidating these communities. Without this, they simply would not have been able to survive that time. This is a very big topic for another time.

And this consecration of Bishop Lazar by the Russian Orthodox Church also served as a time-bomb for further relations with the Patriarchate. When we received the invitation to attend the millennial celebrations in 1988, our hierarchs could not do so, because, in 1982, a catacomb ROCOR bishop had been consecrated in Moscow. Also, in 1996, I met with Schema-metropolitans Epifanii in Belarus and Feodosii in the North Caucasus. And here in Jordanville we had Hierodeacon Zosima (Nikuliak), a gardener. Father Zosima seemed to me a doctor of the Church by comparison with these Catacomb bishops; he had a broad understanding of the realities of life around him, of the need to communicate. Our understanding was also narrowing, but with them, there was just no need for it. “If you want to recognize us,” they would say, “then do; we have no intention of proving anything to you. We do not need to. What for? We are fine as we are.” That’s what struck me: this self-sufficient existence of communicating only with like-minded people.

The ROCOR catacomb community in Kharkiv. Left to right nun Amvrosiia (Polchaninova), Klavdia, rasaphor nun Tamara, rasaphor nun Eliseia (Shura), visiting A. Psarev. July 1996

This is why, under the omophorion of the Russian Orthodox Church in Russia, there were certain disputes in the Catacomb Church, various frictions, and mutual discontent. Sooner or later, this could not but explode. What happened in Russia in 2001 was, it seems to me, the consequence of a delayed effect of an unresolved problem. It was centrifugal. These centrifugal forces were neutralized at a certain moment and for a certain period of time by joining the ROCOR. An immediate trigger was provided by several letters from the ROCOR Synod of Bishops in 2001. Many of the clergy in Russia felt that their continued existence as ROCOR clergy in Russia was being questioned. Proceeding from the fact that the church had adopted a general policy of rapprochement with the Moscow Patriarchate, all the theses of the Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church (the Suzdal “jurisdiction” of former Bishop Valentin Rusantsov) about becoming autonomous from the administrative center of the Church Abroad acquired a new urgency. Amidst all the excitement and discussion in Voronezh, there a meeting in the run-up to the 2001 ROCOR Council of Bishops, attended by the Russian hierarchs. Bishops Lazar, Benjamin, and Agafangel gave talks in Voronezh. By then, it was already clear that they would stay out of the unification process, and something like “Suzdal 2” or even “Suzdal 3” would happen (it was not the first time). They – Vladyka Lazar and Veniamin – had made several attempts to separate themselves from the ROCOR synod in 1993 and later.

But here is my question. As we know, the Lord said that the “gates of hell would not prevail against [the Church]” (Matt. 16:18). But it works out that all that is left of the Russian Church is this catacomb movement we are talking about. And so the rest is somehow not the Russian Church? Some kind of new fabrication, an ersatz?

Quite right. And here, we must not forget that the Church Abroad brought together only part of the catacombs. Bishop Lazar was a controversial figure, and from the outset, Father Gurii (Pavlov) and many others did not want to join the ROCOR at all while Bishop Lazar officially represented it in Russia. There was a very long history to all of this. Against the backdrop of all these events, I decided to contact Vladyka Lazar directly and ask about his view of the situation. I went to Father Pavel Ivanov’s apartment in Moscow. At that time, Vladyka Laurus was staying there. Vladyka Laurus did not say anything definite to me. Apparently, he did not know anything himself. But he confirmed in general that he saw no future in continuing to support this church movement in Russia at the expense of relations with the Russian Church, i.e. the larger Moscow Patriarchate. For me, of course, with my youthful maximalism, this was completely unacceptable. I told him that, in that case, I would have to leave. Vladyka Laurus, with his great pastoral experience and discernment, did not dissuade me. He, to my mind, did not even forbid me. As I was leaving, he said a few words that stuck in my mind. It was the last thing I heard from him personally. He said: “I hope you don’t get lost in these catacombs.” I said something back, but as the years went by, in general, I began to realize that I was really getting more and more confused. That Vladyka had had such an experience of his own and he was saying this based on a kind of active knowledge. He was very perceptive spiritually. In a sense, it became, if not prophetic, then a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Vladyka Laurus, with his great pastoral experience and discernment, did not dissuade me. As I was leaving, he said a few words that stuck in my mind. He said: “I hope you don’t get lost in these catacombs.”

Yes, Vladyka was like that. I remember how I got married and started, one might say say, living my own life. At some point, I came to see him. He gave me an expressive look and said, “Do you want to be on your own?” And went on typing on the computer or whatever else he was doing. The important thing was the way he said it. He really captured the quintessence of it. As to all of the bishops who wanted to leave the ROCOR, Vladyka let them go. Then, before re-unification, he gave letters of canonical dismissal to the Greek Old Believers with whom we were still in communion. If they had parishes, he said not to take the parish away. “We’ll sue you over the parish.” These people with whom he had served for many years and who were his fellow servants. That’s how he let them go. Like the father of the prodigal son: he knew what he would do after getting what he wanted, and yet still gave him what he asked for.

Yes, yes. That’s how it worked out. In my case, I was very quickly accepted into the newly formed diocese of Archbishop Varnava after the 2001 Council. It so happened that I was the senior priest there, a dean, even, in a sense. In the same parish, there were several priests who later became metropolitans: Valerii Rozhnov, Damaskin Balabanov. In fact, things were not very smooth, either. All of these Russian parishes began to fragment and splinter. I won’t go into the details. We all were all waiting in Russia for the end of the All-Diaspora Council in 2006. We had great hopes that the ROCOR might somehow put the brakes on the unification process at the Council or in some sense form an alternative ROCOR. We thought that maybe there would be a large number of dissenting bishops, parishioners. That is, what was happening abroad was completely incomprehensible from Russia. I must say that when I was living in Jordanville in the summer of 1998 and was ordained there, many Church Abroad priests told me: “You have invented your own foreign church in Russia. That is, you have your own vision of Russia. We’re not really like that.” But since when this split occurred with the ROCOR-MP, as we began to call it amongst ourselves, and the ROCOR-A (for Agafangel), we thought at the time that Bishop Agafangel had the support of several other bishops. We had great hopes for Vladyka Daniil, and even Vladyka Gavriil and many others. But they chose their own path. And it was in a sense a relative comfort to us in Russia that the ordinations were performed, along with Vladyka Agafangel, by Greeks from the Old-Calendar Holy Synod in Resistance. That these were Greeks with whom we had been in communion for a long time.

Father Oleg, forgive me for interrupting. You that Mother Margarita had this intuition. Is this your so-called reading of Mother Margarita?

Singing of church hymns after the lay service on the feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. Kharkiv. July 21, 1996. Photo: A.Psarev

It emerged out of direct conversations with her, things she told me herself, directly. When I stopped commemorating Vladyka Laurus, about two months before, she came up to me and said: “I had a dream about you today,” and told me the dream. It was a dream about Father Nikandr, a priest she knew, who she said at least predicted the future of what would happen to the Voronezh communities. And I must say that, now, after 20 years, in general, everything came true. I did not believe her vision at the time. I told her that it could not be. She told me that there would be only one catacomb bishop left out of the entire ROCOR synod who could support us. But until then, we had no right, as she put it, to break off communion with the Church Abroad, because this was the anchor that was keeping us together with Ecumenical Orthodoxy.

I see. That is, she continued to commemorate Vladyka Laurus, while you went with Vladyka Varnava in 2001. What year did Mother Margarita pass away?

You know, I can’t say for sure. She was still alive for at least a few years after that. I don’t think she survived to see the reunification. I think she died a little earlier. Her successor, Mother Miropiia, was of one mind with her in this respect, though she supported me very much in human and personal terms, even financially. But she, too, stayed where she was. It was a great blow for the parish. Fortunately, almost everyone returned in time, but still.

Almost all the young people left Mother Margarita’s parish. The only ones left were the elderly and middle-aged nuns. We organized a youth parish of sorts. Everyone was very zealous and believed that our elders had simply run out of steam on the path of confession and we could take up their baton, and even support them in some ways. But practice showed that we were too presumptuous.

On the whole we ourselves gradually began to turn into ecumenists, into Sergianists. We began to commit the same sins that we had seen, and for which we had blamed the church at large, by which I mean the larger ROCOR.

We had no conflicts with Mother Margarita. We disagreed with the general trajectory of rapprochement with the Moscow Patriarchate. Mother Margarita, as I said, was afraid to the very end of losing the anchor of the Church Abroad, knowing what she would encounter in the catacombs without this canonical foundation. We did not know that. We thought that we could build church life on this mosaic of, you know, different kinds of church catacomb jurisdictions, some that mutually recognized each other, others that did not, and all the rest. Time has shown that this was totally wrong. Of the parish with which I departed the ROCOR, there are now no more than 6 or 7 people left out of a total of 60.

Most returned to the Moscow Patriarchate after reunification – over the years, simply through seeing some kind of dead end, the futility and fruitlessness of resistance to the church. On the whole, and I may say more about this later, we gradually began to turn into ecumenists and Sergianists. We began to commit the same sins that we had seen, and for which we had blamed the church at large, by which I mean the larger ROCOR.

What happened was the following. In 2007, this congregation that I was serving… There wasn’t any turnover at the time. We had a deacon and several priests in this district. Anyway, we went back to Bishop Agafangel, believing that this was the Church Abroad that had shrunk down to one bishop or to the three ordained with assistance from the Greeks, and that we could somehow continue church life in Russia under their omophorion. Soon, our little All-Diaspora Assembly or Council was convoked at the Tolstoy Farm near New York City. I was a delegate at it. The very holding of this meeting revealed the many internal contradictions at the heart of our separation, problems with self-identification and patchwork ecclesiology. Many delegates to our convention had ideas about church praxis, reception into the church, and other issues that, if not diametrically opposed, were very distant from each other. And there was a great muddle in everything.

And a lack of dialogue, a lack of talking, of listening. All of this, I think, was there in full force.

Well, yes. There was a great desire to insist on one’s point of view. That is, people talked more than they listened. This really threw me for a loop during the meeting. Nevertheless, at the end of the meeting, I happened to receive an invitation to come to Canada to see the parishes of Bishop Agafangel here. On my arrival, it turned out that this parish of Blessed Xenia, in which I have stayed to this day, needed a priest. That there was a vacancy here after the death of Father Georgii Skrynnikov, who also did not support all this. And so the question of moving to Canada with my wife and children. The parish council was ready to invite us here permanently. Personally, by this time, I had a rather pessimistic view of the prospects for church life in Russia. I realized that we were not needed there, that there was no need for the message that we had hoped to bring there. I realized that mainstream church life in Russia was in the Moscow Patriarchate. This was probably one of the reasons we decided to move.

Upon getting to Canada, I encountered a very peculiar attitude toward the priesthood on the part of our parishioners. It was a great revelation to me to see the great influence that the parish council had on the life of the church. I was at once made to see that I was only a paid employee in this parish, and had to listen in all things to the opinion of my employers, that it was their prerogative to determine the course of church life and even the content of the sermon. If it didn’t suit any of the influential members of our parish council, I could be told, “Father Oleg, you know, we think that here you are interfering in politics, and here you are saying something wrong.” I tried to argue that St. John the Baptist was also accused of meddling in politics, and that pastoral activity is not essentially limited to performing ritual services. Here, there was a notion that the role of the priest was only to emerge with the censer at the right time, to intone an exclamation at the right time, not to drag out the sermon for more than 10 minutes (or better yet, 5 minutes) so that people would have a chance to go down, to interact, to talk. Gradually, I think the situation began to change, especially in recent years. It seems that we have managed to break through the impenetrable wall, as it seemed to me. Our parishioners are very good, wonderful, faithful, Orthodox people. And in terms of everyday life, in terms of communication, in terms of their performance of Christian duties, there have never been any major problems with them. The only peculiar thing about them, perhaps, was that initially they judged all the people who had recently arrived from abroad based on a very strict scale of compliance with certain values, with some unwritten criteria of “foreignness”.

The one criterion that cannot be altered is that one should have been born somewhere else. So despite living here most of my life, I am still a newcomer. That is, that’s just the category in which people think, that if someone’s from there, he’s a newcomer.

During my years living in Canada, I have repeatedly drawn the attention of our priesthood to the destructive forces at work within the body of our Church. I had repeated conversations with our former first hierarch, Metropolitan Agafangel, about what he has come to call Old Calendarist ecumenism. This is a particular notion that the church or the true church in this case has been divided into branches that differ in their teaching and life, may not recognize each other, may not serve each other, but in some mystical way nevertheless constitute the true body of Christ simply by the fact of their opposition to so-called official orthodoxy. That is, that the church will unite into one body from schisms and divisions, as stated in the anathema adopted in 1983. I even joked, bitterly, that we were falling under our own anathema. Vladyka, I said, look at what we are, that, let us say, in Mansonville, Quebec, with three or four synods competing with each other. Yet we consider all of them by default to be confessors or belonging to some invisible outer church.

What more can I say about this? According to my observations, the attempts of each of these synods to find their own identity were cultivated or developed into some unchurched or barely churched doctrine, views that at other times might have been called marginal. It could have been anything. I don’t know, veneration of Tsar Ivan the Terrible or a special attitude toward the Imieslavs who were expelled from Mount Athos in 1913. It seemed to me that these different groups were trying to assert themselves through their peculiarities, to find their own banner under which they could attract their followers and thus distinguish themselves from the others, accusing them of not sharing this or that point of view, since some residual notion that the church is still “one” has been and is preserved in all these groups. Interestingly, many of these groups are led by or include very godly people. I can say that even our synod, formerly that of Vladyka Andronik, is headed by an absolutely wonderful man. Vladyka Andronik, from my point of view, as a monk – and I have seen quite a few monks in my life – is a rare example of spontaneity, absolute spontaneity, unsparingness, forgiveness, and a readiness to pray. He has so many personal virtues.

For many others, it’s the same story. Let us say that in Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church, the True Orthodox Church now led by Metropolitan Tikhon (Pasechnik), is the church eventually joined by Mother Margarita’s original congregation in Voronezh. Their whole church life was colored by a series of, if not scandals, then internal splits and divisions. On what grounds? For example, one of their bishops, Germogen, formerly Nikolai, was a good acquaintance and spiritual friend of Mother Aleksandra (Gubareva) from my parish in Voronezh. She knew him personally and always testified to me that he was a wonderful man of prayer and monk. But here, this wonderful man, having been made a bishop, at some point realized that he had, in his opinion, been baptized wrongly. He put on his episcopal vestments, climbed into a barrel, and crossed himself with the words “The Bishop Germogen is baptized…”, which led to his being placed under ban by Bishop Tikhon’s synod and, naturally, to a great scandal among the faithful. Similar things began to accumulate in our small synod over the years. Especially after our separation from Bishop Agafangel in 2016. That’s another example with a large church.

Father Oleg, you mention ecumenism. What remains unanswered are the aspirations that the members of the Council of Bishops expressed to our hierarchs in 2006 that the Church Abroad continue to insist on the ROC’s withdrawal from the World Council of Churches. What is your view on this particular issue?

You know, of course, I supported this desire for our hierarchy with all my might at the time and I support it now. For me, frankly speaking, one of the last straws that tipped my personal scales in favor of the decision to return to the ROCOR was the cooling of relations between our church leadership in Moscow and international organizations as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. As we know from the Orthodox Catechism, the Lord often turns even evil arising from the evasion of free will or goodness, into good. It seems to me that the degree of involvement of our hierarchs in the ecumenical movement has been very seriously limited owing to such providential actions, perhaps even against the wishes of many of these hierarchs. This seems to me to be a very positive thing. That is, in such a terrible way, the Lord may lead the Church to recover, to overcome some internal temptation.

If we go back in history, there was a similar situation when the Byzantine Empire fell, when all the hopes of Uniates or, rather, hopes for Christian unity were tested by sword and fire. In the present case, I think we are on the way to finding a new balance in this respect, one that may be more acceptable in terms of such traditional, foreign, if you will, views on the admissibility of our church’s participating in the ecumenical movement. Although, of course, I understand the history of the ecumenical movement and the real involvement of our hierarchs in it. But it just seems to me that, in this case, the role of Christian unity in building up the church is overestimated. Despite the official rhetoric about witnessing to Orthodoxy, in Soviet times, the Russian Orthodox Church participated in the ecumenical movement mainly in order to soften the pressure on itself from the godless authorities.

Therefore, at present, the very aggravation of not only inter-Orthodox, but also inter-Christian relations in recent times, to the point of breaking off prayerful communion between Constantinople and Moscow or the formation of the African exarchate, ultimately comes down to different assessments of the events in Ukraine. A number of the ancient Orthodox Churches support it, while the Russian Church is in a defensive position. In my view, this should lead to a new rethinking of the role and place of the ecumenical movement in the life of the church. So I have no doubt that we are on the right track. That is, sooner or later this will lead to a new balance. There will be a regrouping.

Thank you. That is, in the events following the All-Diaspora Council, you see no analogy with the Union of Brest in 1596, when the Orthodox in Western Ruthenia began to commemorate the Pope of Rome?

I don’t. When this happened 15 years ago, it seemed to me to be a fair enough assessment of things, the comparison with Uniatism. But I can just give you just one example from those 15 years. In our own little synod a couple of years ago, without any involvement on my part, it was decided to re-baptize all who came to us from official jurisdictions even up to the point of chrismation – that is, even those who had not been baptized in the Orthodox way through immersion and who had been received into Orthodoxy through chrismation. I tried to raise the question of this not corresponding to the canonical practice of any local church. But, unfortunately, I was not heard. Moreover, it led to very unfortunate incidents when groups of, say, believers from other jurisdictions tried to join us or came back from our own, or moved from one parish to another. Even in our Toronto parish, a large group of parishioners were not accepted from our other parish because they had been baptized by affusion. You see, these are people from our synod. If they were in full prayerful Eucharistic communion, then requiring them to be baptized retroactively was even more incongruous, in my view, than requiring parishioners from other local churches to be received through either one rite or the other. That is, not through repentance, but through chrismation or baptism. Unfortunately, all the so-called “remnant ROCOR” jurisdictions, if you can call them that, have developed absolutely Zealot, non-Orthodox expressions.

So there has to be a kind of “otherness”?

And this otherness tends to be pushed by active priests. Bishops often fall under the influence of one or another group of extremists who impose their point of view on everyone. And clergy who do not agree with this are simply pushed beyond the boundaries of this circle of like-minded people.

Again, there is no dialogue. People don’t ask questions: they make assertions.

When I expressed my disagreement with this, I simply stopped receiving invitations to diocesan meetings, even though I was, in principle, the secretary of the Canadian diocese of Vladyka Andronik’s synod. This is just one example. And there was no reference to the Holy Fathers, to the practice, to the danger of baptism, because we believe in one baptism, no reference to elementary logic… I tried to explain to Vladyka Andronik in my last conversation with him that if he insists on re-baptizing parishioners who have already received communion with us, that is, if he insists on reexamining their baptism into the Orthodox Church, then he himself is not ordained, since he was ordained by Bishop Agafangel, who, in turn, was baptized by affusion. After all, no one rebaptized him when he was received into the Russian Church Abroad, either when he was consecrated a bishop or subsequently. Even such apparent contradictions do not stop people from persisting in knowingly erroneous views. Therefore, this is a very great common weakness, or rather the Achilles’ heel, of all these newly formed groups.

Father Oleg, this has been an informative conversation. I hope that we can continue to talk and that, God willing, a conciliar process will begin or continue in our Church, and that you will be able to take part in it. Thank you very much for the conversation.

Thank you, too.

Conducted by Protodeacon Andrei Psarev

It’s fascinating to hear Fr. Oleg saying that people need to listen to one another on the one hand (in the various splinters from Russian Orthodoxy), and on the other that listening is bad (the ecumenical movement). Halfway to that kenotic compassion of Christ – so close and yet so far. He resents always being that foreign guy in Canada, and yet non-[Russian?] Orthodox Christians aren’t worth reaching out and listening to.

Re: “…one of the last straws that tipped my personal scales in favor of the decision to return to the ROCOR was the cooling of relations between our church leadership in Moscow and international organizations as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. As we know from the Orthodox Catechism, the Lord often turns even evil arising from the evasion of free will or goodness, into good. It seems to me that the degree of involvement of our hierarchs in the ecumenical movement has been very seriously limited owing to such providential actions…”.

Fr. Oleg does not realize that what he observes as the “cooling of relations” between the Moscow Patriarchate-ROCOR and other non-Orthodox Christian bodies is not a discrete religious phenomena within the ecumenical movement, but it is rather a symptom of something larger, an almost universal moral disgust (outside of Russian Orthodox circles if course) at the complicity of the Moscow-Patriarchate-ROCOR in this fratricidal war.

This “cooling of relations” represents a kind of little “e” ecumenism where the MP-ROCOR serves as the unifying factor.