From the Editor

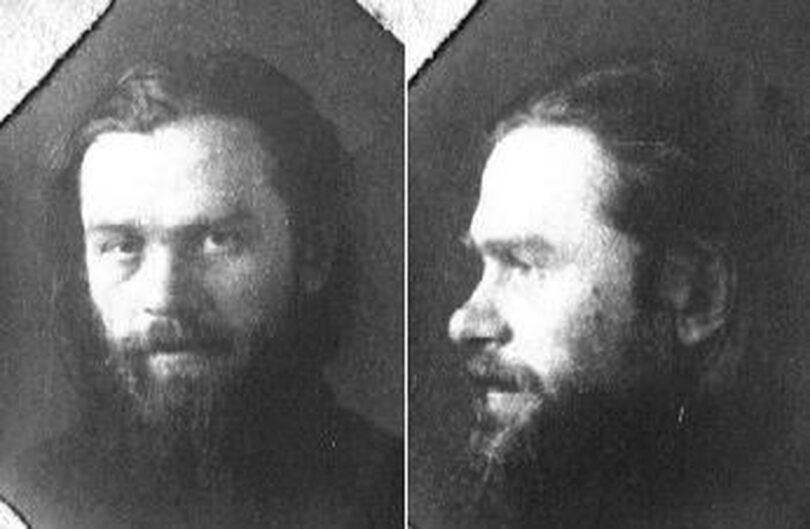

In Soviet Russia, Archpriest Michael Polsky (1891–1960) belonged to the movement of “non-commemorators”, that is, clergymen who invoked the name of Patriarchal Locum Tenens Metropolitan Peter Polianskii of Krutitsa at services, but not that of his deputy, Metropolitan Sergius Stargorodskii, because they considered the latter to have usurped authority in the church after 1927. In 1930, Father Michael crossed the border into Persia; he would serve in the ROCOR from August of that year until his passing. During World War II, Father Michael was the priest of the Dormition parish in London, which was under Archbishop Vitaly Maximenko of Jersey City. The hierarchy of the North American Metropolia, of which Archbishop Vitaly was a part, recognized the patriarchal election of Patriarch Sergius Stargorodskii in 1944 and gave a blessing for his name to be commemorated liturgically in churches. Although Archbishop Vitaly signed that decision he permitted Fr. Michael not to commemorate Patriarch Sergius. (His fellow priest Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes refused this course of action.) In November 1946, at the Seventh All-American Council in Cleveland, Ohio, the North American Metropolia adopted a resolution to exit the ROCOR. After this, ROCOR dioceses were reconstituted by ROCOR bishops who since 1935 had been incorporated into the Metropolia. In 1948, Father Michael became part of the clergy of the Holy Virgin Cathedral in San Francisco. That same year, he served as an expert witness in the legal dispute between the ROCOR and the North American Metropolia over the ownership of Holy Transfiguration Church in Los Angeles. As a result of the preparations for the trial, in which the ROCOR ultimately came out on top, Father Michael wrote his work Kanonicheskoe polozhenie vysshei tserkovnoi vlasti v SSSR i Zagranitsei [The Canonical Status of Supreme Church Authority in the USSR and Abroad ], which was printed in 1948 by Saint Job of Pochaev Press at Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville. Before the revolution, Father Michael had been a diocesan missionary in Stavropol Diocese, and his anti-sectarian, polemical attitude found expression in this work, which served as a catalyst for discussion of the ROCOR’s canonical status. That same year, Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann published a reivew of Father Michael’s book, titled Tserkovʹ i tserkovnoe ustroistvo [The Church and Her Structure]. In 1949, Father Alexander’s review of Father Michael’s book received three responses, from Bishop Nathaniel Lvov (“O sudʹbakh Russkoi Tserkvi Zagranitsei” [“On the Destiny of the Russian Church Abroad”]), Archpriest George Grabbe (“Kanonicheskoe osnovanie Russkoi Zarubezhnoi Tserkvi” [“The Canonical Basis of the Russian Church Abroad”]), and Archpriest Mikhail Pomazanskii (“Nashe tserkovnoe pravosoznanie” [“The Legal Consciousness of Our Church”|]). In the following year (1950), Father Alexander replied to Bishop Nathaniel and Fr. George with the article “Spor o tserkvi” (“The Dispute over the Church”). In response, Bishop Nathaniel published a piece titled “Pomestnyi printsip i edinstvo Tserkvi” [“The Local Principle and the Unity of the Church”]. In 1950, Protopresbyter Grigorii Lomako, an opponent of Father Michael’s from the Metropolia at the trial in Los Angeles, replied to the latter in an brochure titled “Tserkovno-kanonicheskoe polozhenie russkogo rasseianiia” [“The Ecclesiastical Canonical Status of the Russian Diaspora”].

In 1952, elaborating on the topic of non-canonical trajectory of the Paris Exarchate set out below, Father Michael published a brochure titled “Ocherk polozheniia russkogo ekzarkhata vselenskoi iurisdiktsii” [“An Outline of the Status of the Russian Exarchate in the Jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate”], only for Father Alexander Schmemann to reply with another article, “Epilog” [“Epilogue”], that same year. In a brochure published in Munich in 1959, “O nekotorykh vazhneishikh momentakh poslednego perioda zhizni sv. patriarkha Tikhona (1923-1925)” [“On Some Highly Important Moments in the Final Period of the Life of Holy Patriarch Tikhon (1923–1925)”], Archpriest Vasilii Vinogradov pointed out imprecisions in Father Michael’s book.

The book O nepravde Karlovatskogo raskola [On the Unrighteousness of the Karlovci Schism] by the pre-revolutionary canonist S. V. Troitskii, published in Paris in 1961, drew the greatest amount of attention of all to Father Michael’s work. Prof. Troitskii’s book must be considered in the context of the prewar polemics surrounding his works on the canonical organization of the Russian diaspora church. Defending Father Michael’s conception, Archpriest George Grabbe replied with a book Pravda o Russkoi Tserkvi na rodine i za rubezhom [The Truth About the Russian Church in Russia and Abroad], published in Jordanville in 1961. The publication of Troitskii’s book sparked a discussion in print that was only tangentially relevant to Father Michael’s work.

The bulk of Father Michael’s book was about the status of the church in the USSR, and its structure and line of argument follow that of the typewritten Josephite anthology “Delo mitropolita Sergiia” [“The Case of Metropolitan Sergius”] (1929). Since our Internet hub is dedicated to the Russian Church Abroad, I would like to commend to your attention the chapters from Polsky’s book that cover the Russian diaspora. This translation has been made possible by a grant from the American Russian Aid Association – Otrada, Inc.

Deacon Andrei Psarev, June 17, 2021

9. The Bishops’ Council and the Synod

The canonical position of the portion of the Russian Church that is abroad, as soon as it could be developed due to the disruption of communications with its Mother Russian Church, has to be defined, as we must assume according to necessary logical consistency, by its relationship with the Supreme Church Authority in the USSR and with the Russian Church in general. As part of the Russian Church it must regard itself as being within it and to be bound by duty to be faithful to it. By virtue of this same faithfulness to the Russian Church its portion abroad must refrain from submission to it until the time when the Russian Church obtains freedom and settles its matters at its free local council.

This is the meaning of faithfulness to the Russian Church in its trials and sufferings on the part of its portion abroad, and of faithfulness to the holy canons.

It is unlikely that other criteria might exist to make judgments about its canonicity.

The Supreme Church Authority

According to Apostolic Canon 34 “It behooves Bishops of any nation to know the one among them who is the premier or chief and to recognize him as their head, and to refrain from doing anything superfluous without his advice and approval.” Therefore, any kind of new church administration within the Russian Church could only arise with the permission or sanction of the patriarch and his Synod and Council.

Having been isolated from the center by the front of a nearly three-year military conflict the southwestern part of Russia had to self-govern itself somehow, and in May of 1919 the South Russian Holy Council took place in Stavropol in the Caucasus, which established the Temporary Supreme Church Authority in Southwest Russia, uniting several extensive dioceses.

The establishment of this Supreme Church Authority received recognition later by the patriarch and his administrative organs in the highest manifestations of his authority. These included the consecration of bishops (Seraphim of Lubny, Andrei of Mariupol), the appointment of bishops to sees (in Russia, Ekaterinoslav, and abroad, in Europe and America), trial over bishops (Sergii Lavrov, Agapit of Ekaterinoslav), and release to retirement (Ioann of the Kuban).

Thus, this conciliarly organized authority was a canonical establishment, due both to the means of its formation by a council and to the acknowledgment of its directives by the Central All-Russian Church Authorities.

After the Civil War, at the end of 1920, the large Russian flock came abroad. Up to two and a half million people, along with their bishops and priests, distributed themselves in various countries, with some of them going into already existing parishes but with most establishing many new ones. The properties of the Russian Church were expanded abroad. Dioceses in America, the Far East, Persia, Palestine, and parish and embassy churches in Europe and South America had existed for a long time.

The Russians who found themselves abroad had their own church organization as well.

In November of 1920 the Russian hierarchs had their first Council in Constantinople, which changed the name of the Southern Church Authority of Russia to the Supreme Russian Church Authority Abroad, and from then on this Council has met annually, according to the canons. In 1921 the church administration moved to Yugoslavia.

The presence of the large Russian Orthodox flock, dispersed among various countries, of sizeable church properties in missions, parishes, and dioceses, and a large number of Russian bishops abroad, both those who had lost their sees in Russia and those who had been at theirs here abroad necessitated the organization of this portion that was abroad, as an unshakeable inheritance of the Russian Local Autocephalous Church into a single body, and to maintain it as such until it again comes under its one ecclesiastical All-Russian authority.

Given the unity of interests of all the Russian people abroad who feel and think of themselves as Russian and Orthodox and are awaiting either a return to Russia or a prospect of being under its previous spiritual care and protection, it was natural to seek abroad a single spiritual center and guidance toward this general aim. It turned out that enough bishops were here to organize all church life on the basis of self-rule on the principle of conciliar church law.

Thus, the Bishops’ Council could be formed by the entry into it of the entire existing complement of Russian hierarchs who were abroad, and many of them, such as the bishops of Finland, Lithuania, Harbin, and Peking had permanent sees and complete administrative independence. The unified episcopate obtained all the fullness of ecclesiastical authority over all Russian churches abroad temporarily until the time when the abroad portion would again flow into the course of the Russian Church. The Supreme Church Authority in Southwest Russia already possessed this fullness of authority.

Such conciliar administration by part of the Church is canonical by its structure, since the conciliarity of the supreme power is established by canons of universal significance.

The canonicity of a council is determined by the general presence of bishops who are vested in supreme grace and are successors to the apostles, independently of the degree of their administrative rights. As we already stated, it included bishops who had been ruling abroad and those who again received sees in newly established dioceses after losing other sees and leaving their dioceses not of their own accord but because of persecutions by enemies of the faith. According to the holy canons they maintain episcopal honor and service while in exile as well. They perform ordinations to various clerical ranks, and make use of the privileges of their seniority according to their limits, and “any action of leadership coming from them is recognized as firm and lawful ” (Antioch 18, 6th Council 37).

The Supreme Russian Church Authority Abroad, and then the Bishops’ Synod, became the executive organ of the Bishops’ Council for the interconciliar period. Thirty-four bishops were entered into the actual Council through personal or written participation. Here are their names:

Antonii, Metropolitan of Kiev and Halych, Chairman of the Bishops’ Council and of the Supreme Church Authority, Antonii, Bishop of the Aleuts. Anastasii, Archbishop of Kishinev, Alexander, of Archbishop of North America, Bishop Adam, Apollinarii, Bishop of Belgorod, Director of the Jerusalem Mission, Vladimir, Bishop of Bielostok, Veniamin, Bishop of Sevastopol, Gavriil, Bishop of Chelyabinsk, Germogen, Bishop of Ekaterinoslav, administering in Greece, Africa, and Cyprus, Daniil, Bishop of Tsaritsyn, head of the Pastoral – Theological Academy, Daniil, Bishop of Okhotsk, Elevferii, Archbishop of Lithuania, Euthymius, Archbishop of Brooklyn, Evlogii, Metropolitan of Western Europe, Innokentii, Archbishop of Peking, Mar-Il’ia, Bishop of Urmia, Iona, Bishop of Tian-Tsin, Mefodii, Archbishop of Harbin, Meletii, Bishop of the Trans-Baikal, Mikhail, Bishop of Alexandrovsk, Mikhail, Bishop of Vladivostok, Nestor, Bishop of Kamchatka, Panteleimon, Archbishop of Pinsk, Platon, Metropolitan of North America, Seraphim, Archbishop of Finland, Seraphim, Bishop of Lubna, administering in Bulgaria, Sergii, Bishop of Belsk, Sergii, Bishop of the Black Sea, Sergii, Archbishop of Japan, Stephan, Bishop of Pittsburgh, Simon, Bishop of Shanghai, Feofan, Bishop of Poltava, Feofan, Bishop of Kursk, (Ioann, Bishop of Latvia was denied participation in the Council due to local political conditions).

The Bishops’ Synod

In difficult compromises with Soviet authorities, hoping to gain any kind of easing of persecution. Patriarch Tikhon issued a decree on April 22/May 5, 1922 shutting down the Supreme Church Authority. The Soviet regime, in order to destroy its opponent who had gone abroad, acted through its Church authorities, making deceitful promises. The unlawful motives of this act, that are indicated in it — “for political speeches without any canonical basis’ — have already been mentioned.

In response to this decree the Bishops’ Council ruled on August 31/September 13, 1922 that the Supreme Church Authority would be abolished in compliance with the directive of the patriarch and his Synod and the Council, on the basis of Decree 362 of November 7/20, 1920 by the patriarch and the same administrative organs, to organize the Temporary Holy Bishops’ Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.

Thus, the supreme canonical organ of church authority abroad is the Bishops’ Synod, which has not been shut down nor dissolved by any decree, and remains in force in order to replace the Supreme Church Authority as its executive organ with another, the Bishops’ Synod. That the Bishops’ Synod made the correct decision by changing to a new basis for continuing the existence of its administration, is shown by the actions of church authorities at this moment in Russia itself.

With the decree of May 5 the Patriarch shut down the Church Authority Abroad, and a few days later gave “all the “fulness of authority” to Agafangel on the basis of the 1920 decree, who in a missive of June 18 asked hierarchs to “administer their dioceses independently,” in other words, in accordance with the same decree. At that moment the 1920 decree went into effect and only later was rejected by Sergii in principle, since he wished to retain church authority and agreed to compromises of legalization, going into schism with the episcopate.

The 1920 decree was issued not for that year, but for when the moment that was indicated there would come, in other words when the activity of the patriarch and of other supreme church organs ceases. That is what happened at the moment when the decree shutting down the church authority was received abroad.

Thus, the external situation and the already existing law, coinciding with the situation, and going into effect just at that moment, necessarily obliged the Bishops’ Synod to open up a new church administration abroad on a new basis. As the leader of a part of the Russian Church, the Council of its bishops could do nothing without deliberation or against the will of the first hierarch, and shut down the church authority on the basis one of his directives, and on the basis of another, which was going into effect at that moment, opened up another one, because the need for it remained the same for the abroad, the same as yesterday.

According to the new law of its existence the church authority abroad received independence, and due to its condition of permanent isolation from the Russian ecclesiastical center it had permission for self-government. If in Russia the connection of dioceses with the center, even with it being present, was unrealized, and the dioceses were in fact being administered independently in the era of persecutions, the law, at the moment of the loss of conciliar organs of administration and of the replacement of the first hierarch with arbitrary substitutes, acquired exclusive significance for the Russian Church Abroad according to the conditions of its life and even greater isolation from its center.

Thus, the law of decentralization, of local administration in connection with persecution of the Church in Russia and the isolation of parts of the Church with its center, became the basis and ground of the ecclesiastical authority of the Bishops’ Synod Abroad.

The Southwestern Church Authority, which was created back in Russia was probably a precedent for the patriarch to issue at least a few positions on the law of decentralization in 1920, and the Bishops’ Synod, being the rightful successor of the of that church authority in Russia, which was recognized by the Patriarchate, was established anew on an indisputably canonical basis here in the part of the Russian Church that is abroad.

In its very essence the decree abolishing the authority abroad had only the formal sense of the patriarch’s compromise with the Bolsheviks due to the demands of the moment, and was formally accepted by the Bishops’ Synod, which abolished this authority, but preserved the essence of the matter, the church authority abroad, as the Bishops’ Synod. This placed the law of local self-rule, which was being put into practice, on a new basis. It is also of essence that, in accordance with it, the new establishment, which is organized locally by conciliar authority, and is confirmed in advance by the central ecclesiastical authority, is accountable to it and awaits its sanctions regarding its own directives upon the restoration of this authority and of this establishment’s connection with it.

The Bishops’ Synod informed the Patriarch of Moscow about its activity, but the patriarch could express his attitude toward its existence only by silent agreement, since the Bolsheviks have repeatedly regarded the Patriarchate’s interaction with the White emigré clergy as a political crime. And yet, in his telegram and letter regarding matters of the Harbin Diocese and the dispute regarding the Czechoslovak jurisdiction the patriarch definitely took into account, as before, during the rule of the Supreme Church Authority, the decision of the hierarchs abroad. The previous activity of the Bishops’ Council continued, and no censure of its activity followed, neither from the patriarch nor from those who took his place, despite the Bolsheviks’ demands. To all this we must claim categorically that the canonicity of the single church authority abroad, from the moment of its appearance, has never been subject to any doubt. And this authority, when it was the Bishops’ Synod, was defended there by the Russian episcopate from Bolshevik encroachments up until 1927, All of this is apparent from the preceding account as well.

Relations with the Sergian Patriarchate

The question of whom to follow, the first hierarch, who had betrayed the Church or the Church against him and the godless power, with whom he had entered into union, was decided definitely for the Bishops’ Council and for the entire Russian immigration by its entire preceding activity. Throughout all those years it spoke out as an incessant defender of the Russian Church before all the autocephalous churches and even world governments for any reason or event within it., such as new outbreaks of persecution of the Church, the patriarch’s interment, the renovationist schism, and so on.

The Patriarch’s directive to abolish the Church Authority Abroad was unlawful in its motives at the time that it was issued, being clearly dictated by the force of godlessness, and demonstrated the Patriarchate’s total lack of knowledge regarding the state of the Russian Church abroad. But the Council Abroad had only a certain forewarning about this in case of a similar or even worse attitude in the future, and sought interaction, support from the Patriarchate, and administrative guidance, if possible. And now, with the issuance of Metropolitan Sergii’s declaration, it would be insufficient to expect simply normal relations with Russia in order to renew its submission to its ecclesiastical authority. What was needed was not only the liberation of the Church from persecution by the godless, but from the enslavement of its own church authority.

Metropolitan Sergii’s declaration prompted a response by a definite decision. The Bishops’ Council resolved the following: “The part of the All-Russian Church that is abroad must cease administrative relations with Moscow’s church authorities, in view of the impossibility of normal relations with it and in view of its enslavement by the godless Soviet regime, denying it freedom in exercising its will and freedom in the canonical administration of the Church.”

In order to free our hierarchy in Russia from responsibility for the non-recognition of the Soviet regime by the part of our Church that is abroad until the restoration of normal relations and the liberation of our Church from persecutions by the godless Soviet regime it must administer itself, in accordance with the holy canons, the definition of the 1917-1918 Council, and the Patriarch’s resolution of November 7/20, 1920, with the help of the Bishops’ Synod and the Bishops’ Council.

The part of the Russian Church that is abroad considers itself to be an indissoluble spiritually unified branch of the Great Russian Church. It doesn’t separate itself from its Mother Church nor does it regard itself autocephalous. As before, it regards the Patriarchal locum tenens Metropolitan Peter as its head and still commemorates him at services.

Further on, a direct response was needed to this statement in Metropolitan Sergii’s declaration: “We have demanded that the clergy abroad provide a written affirmation of complete loyalty to the Soviet regime in all its social activity. Anyone who does not provide such an affirmation or violates it will be removed from the list of clergy subject to the Moscow Patriarchate.”

The Council stated in the same definition, “If this is followed by Metropolitan Sergii’s and his Synod’s ruling regarding the removal of bishops and clergy who are abroad who refused to sign a statement of loyalty to the Soviet regime from the list of clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate, such a directive will be uncanonical.”

“Metropolitan Sergii’s and his Synod’s suggestion that we sign a statement of loyalty to the Soviet regime should be decidedly rejected as uncanonical and very harmful to the holy Church.”

But these uncanonical actions inevitably followed.

Decree 104 of the Sergian Synod of May 9, 1928 declared that the Bishops’ Council and Synod were abolished and all their actions were repealed.

On June 24, 1934, after fruitless correspondence with Patriarch Varnava of Serbia, this Synod of Metropolitan Sergii “commits the Karlovci group to ecclesiastic trial as having disobeyed the legitimate church leadership and causing schism, with prohibition of serving church services up until a trial or repentance.”

However, the attack became even more serious. Only the last resolution by the Bishops’ Synod of 1927 turned out to be sufficiently foreseeing. A Moscow church delegation appeared abroad, and in this way one reason for the break with Moscow church authorities fell away — “the impossibility of normal relations with it.” But the other reason to “cease administrative relations” with it, “in view of its enslavement by the godless Soviet regime, denying it freedom in exercising its will and freedom in the canonical administration of the Church,” now appeared in full and proven force.

A delegation from the Sergian Patriarchate appeared abroad in 1945, distributing Patriarch Aleksii’s address of August 10 to archpastors and other clergy of the so-called Karlovci group, urging it to offer repentance, or else the 1934 decisions would be confirmed.

In October 1945 Metropolitan Anastasii, chairman of the Bishops’ Synod, issued a message to the Russian Orthodox regarding Patriarch Aleksii’s message in which he affirmed in detail one basic position: “Bishops, other clergy, and laity subject to the jurisdiction of the Bishops’ Synod Abroad have never broken canonical and spiritual unity with its Mother Church. The representatives of the Church Abroad were forced to break only with the Supreme Church Authority in Russia, since it itself has started deviating from the path of Christ’s truth, and in this way to break away spiritually from the Orthodox episcopate of the Russian Church, for whom we do not cease to offer our supplications at each service together with Russian believers, who have remained preservers of piety in Russia from the earliest times.”

For this same reason, the Bishops’ Synod, having united 26 bishops, 16 of whom were present at the Assembly in Munich on April 27/May10, 1946, declared, “We do not find it morally possible for us to agree to these calls as long as the Supreme Church Authority in Russia is in an unnatural union with a godless regime, and as long as the entire Russian Church is denied the true freedom that is natural to it according to its divine nature. The supreme hierarchy of the Russian Church has embarked upon a false path, keeping silent about the truth that is bitter for the Soviet regime, presenting the Church life situation not as it is in reality and consciously declaring the blasphemous lie that there is no persecution of the Church and has never been in Russia, and mocks the suffering exploits of numerous martyrs among the clergy and laity.”

For a final determination of the position of the Bishops’ Synod we will add one more confession of Metropolitan Anastasii: “The Bishops’ Synod has actually always been regarded as a temporary establishment, but not until simply the restoration of relations with the Supreme Church Authority in Russia, but, first of all, until the restoration of a normal general and ecclesiastical life within it. This prerequisite has always been regarded as the most important and basic one in determining the period of the existence and activity of the Council and Synod Abroad. We are basing this on the position that, regrettably, the end of this period is not yet upon us, and on this basis we affirm the necessity of continuing the existence of the Synod.” (Letter of November 14/27, 1945)

The correct path. We must make it a point to remember that the 1920 decree on decentralization was the voice of a free supreme and totally authoritative church administration that is uncompromising toward the Church’s enemies. For the Church Abroad it serves as a basis because it is continually isolated from the Mother Church, and, according to the conditions of its life, it is independent of Soviet constraint and is able to fulfill its duty freely and uncompromisingly. All subsequent directives from Moscow, starting with the 1922 decree, are dubious, since they are dictated by compromises with the Soviet regime and its use of force, and obviously do not correspond to the truth, canons, and Church interests. By relying upon the 1920 directive and guarding against the uncanonical and purely political demands of the Moscow Church authorities the Bishops’ Synod, in its refusal to obey them in 1927, is not indulging in any kind of arbitrariness, willfulness, or violation of obedience to its normal Supreme Central Russian Church Authority. On the contrary, it alone, due to its conditions of freedom, is able to live normally and lawfully, while the Russian Church authorities, due to their constraints, fall away from this norm.

What is most essential and important is that at this very moment the Bishops’ Council here abroad firmly and decisively, without the least amount of doubt, joins the Spiritual Council of the Russian Bishops and along with it condemns the actions of Metropolitan Sergii as unlawful.

The moment that was being so acutely experienced by the Church was understood totally correctly far away from the native land. It was starting with this test that the Bishops Synod became irreproachably canonical, being at one with the Tikhon route. At that time it joined the Russian Church, not nominally but actually, with everything that decisively broke off all administrative relations with the Moscow Patriarchate, and relied once again and more firmly than in 1922 on the decentralization and local administration law, which Metropolitan Sergii did not attain, and he bound part of the episcopate along with him.

These relations with the Church authorities abroad with those under the Soviets have the classic formula in these words “We were obliged to break only with the Supreme Church Authority in Russia since it had started to step away from Christ’s path of truth, and in this way to break away spiritually from the Orthodox episcopate of the Russian Church… together with Russian believers (Metropolitan Anastasii’s Message of October 1945).

Not to recognize the Supreme Church Authority in Russia and to consider itself part of the Russian Church is completely natural and lawful, and there have been many instances in history when the supreme church authority acted unlawfully, and it was fought against, disobeyed, and its fall was awaited. The duty of this struggle always lies on someone, and in this case it lies on that part of the Church which can and must lead it according to its position, and which cannot refuse this duty, for that would be its death and the triumph of lawlessness for the entire Church, which can in no way be allowed.

Thus, from the first days of the struggle in Russia’s South and later in the emigration the Bishops’ Synod took upon itself the mission of witnessing to any truth about the Mother Church, its sorrows and trials, whatever phases it might be experiencing, be it persecution by enemies or betrayal by its own, and it cannot refuse this mission without betraying God.

It is in the interests of the Church in Russia that it be defended abroad, especially when this is not being done by its own Church authorities. The whole mass of the episcopate and other clergy of the Russian Church wishes freedom to the Church abroad as its moral support in struggle. It is full of hope that truth does not fade and is proclaimed somewhere. Sharp blows are experienced there by betrayals to it, by falls. If those abroad fall as well, then where is truth, and who keeps it? The position of the Russian Church Abroad is alacrity and comfort for everyone in Russia who loves the Church. Such is the witness of anyone who has been interred or exiled in Russia and conducted the struggle for the truth about the Church, and then obtained the good fortune of freedom abroad. Documents speak about this, and this is good for the Church. To oppose the Church Abroad in Russia is just as unnatural as opposing oneself. The heart of each Orthodox person in Russia, and even more so in its catacombs, fills up with a sense of profound satisfaction and joy, that the part of the Russian Church that is abroad has not departed from its path of truth and struggle for its Mother.

Hostile actions. Eliminating the administration abroad or submitting it to the authority of the fallen church authority under the Soviet Union would be a task only for the Church’s enemies, the Bolsheviks, while coming out against it by Church authorities is a betrayal of the Church. But this is purely Soviet morality. There, one confined to prison, in order to ease his situation, slanders others who are likewise sent to prison, but both the betrayer and the betrayed are executed. There are absolutely no guarantees of freedom for the Church in Russia in general and for the church betrayer in particular. And it has already been said that going along with such a deal with a known deceiver and sworn enemy of the Church is impossible, and that evil means are not appropriate for good purposes in the Church. Having lost its own freedom, the church authority under the Soviets is trying to take away the freedom of others with great fervor and zeal, violates the conscience of the free, forces the acceptance of already unrighteous slavery, and imposes its language of lies and deception while continuing its shameful statements. This is that same struggle not for the Church but for its own existence, for its own affirmation in the Church, for the avoidance of future judgment and the justification of its uncanonical path. It wishes to compel witnesses against it to silence, so that everyone would submit everywhere and be silenced before it, as it did in Russia.

It is now understandable why the Bishops’ Synod Abroad with its Chairman Metropolitan Anastasii is enemy number one at the Bolsheviks’ church front and for the Sergian Synod.

The Moscow delegate in America, striving to unite the Metropolia with the Patriarchate, said, “There are no more demands, just break with Metropolitan Anastasii.” The first item in the written document giving the prior conditions by the Moscow Patriarchate for removing the prohibitions against the Metropolia’s clergy is “the cessation of canonical and prayerful contact with Metropolitan Anastasii.” (Chicago, December, 14. 1945)

Anything but participation in this front. However, this isn’t sufficient. How can the chairman of the Synod Abroad be stigmatized or discredited in the eyes of the world? There is no material. But Metropolitan Anastasii’s address of gratitude to the German government of June 12, 1938 is presented as a crime.

On February 25, 1938 the German government issued a law preserving Russian Orthodox Church property in all German cities for our Church’s needs, relieving it of debts and lawsuits.

On May 30 / June 12, 1938 Metropolitan Anastasii consecrated a cathedral that was built for the Russians by the German government, which gave the first part of a grant of 45,000 marks, and then more as needed.

The war began a year after this event, on September 3, 1939. A few days before that, on August 23, 1939, the Bolsheviks concluded a non-aggression pact with Germany and jointly divided up Poland, and until the summer of 1941, when they went to war with them themselves, helped Germany against England and France with oil, provisions, and resources. Serbia, where Metropolitan Anastasii was living, was under German occupation from April 6, 1941. So how did Metropolitan Anastasii act from the war’s start in general, and then during Germany’s war with Soviet Russia?

From the start of the war he, along with the Bolsheviks, did not help the Germans in their fight against the Allies, and later he issued no written acts in the Germans’ favor, as did others, such as a certain metropolitan in Paris on June 22, 1941 and a certain archimandrite in Berlin on June 29, 1941.

And how did he act under the occupation? Patriarch Gabriel of Serbia, when he was in London in October of 1945, announced, with a feeling of deep sympathy and personal friendship toward Metropolitan Anastasii, to various Russian, English, and Polish church circles that he had displayed great tact and wisdom under the Germans, was always loyal toward the Serbs, underwent searches several times, and was not trusted by the Germans at all.

This testimony is so authoritative and significant that it dispels any shadow of lies and slanders.

Thus, an expression of a necessary debt of gratitude back before Chamberlain tried to convince Hitler to curb his appetite, while the Bolsheviks whetted it along with him, is made into an accusation by the falsehood of this world against a person simply because back in 1938 he did not express hostility to the German leader when he was building a church for Russians. And public statements with the Germans in no way prevent one to become a Soviet exarch and another one to become an American bishop. Of course, such is their lot in the world, but a true helmsman of an ecclesiastical ship cannot navigate without a wheel and sails at this very hard and troublesome time. Metropolitan Anastasii’s path is one of pure truth, and the slander is proof of this, for there are no other means against him.

One striking fact demonstrates the significance that the Bishops’ Synod and its truth have for Russia. Number 9 of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate for 1946 has two articles directed against the Synod by Archpriests D. Bogoliubov and M. Vikentiev (Arkhireiskii Sobor zagranitsei and escho odin Miunkhen, pp. 74-80). But what a surprise it was when this article could not be found in another copy of the same number which was obtained through other means. Thus, Russian readers cannot be given information about the truth for which the Bishops’ Synod is fighting, even in the form of polemics.

Faithfulness. The irreconcilable position of the Bishops’ Synod is the position of those who are languishing in prison to this day, while many have been executed. The Russian Church Abroad confesses the truths of those nine hierarchs of the camps of the Molotov (Perm) Region who refused to sign their agreement with the Moscow Patriarchate and be released. It relies on that mass of believers with whom the Chekist on Church Affairs George Karpov polemicizes. He tells his Council of Bishops that the change in the relationship between the Church and the government “is not a tactical maneuver, as certain ill-wishers try to present this matter or as it is sometimes expressed in philistine discussions.” (Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, 1944:12) As in Russia, such discussions are held by Russians abroad as well.

The faithfulness of the Russian Church lies in remaining within it and not submitting to its current Patriarchate as being unlawful, lacking authority, not representing the Church, and in the conditions of its freedom preserving the banner of lawfulness and truth, raising it high, and awaiting and demanding its restoration and triumph. And this task of the Russian Church Abroad has been fulfilled and is being fulfilled among temptations, threats, prohibitions, lies, and slanders by enemies, treason and betrayal by its own, either through silence or through attacks in the press.

The Russian Church Abroad, with the Bishops’ Council and Synod at its head, not only confesses itself, but is actually within the Russian Church. It never broke away from it, living by its interests, needs, struggles, truth, defense of canons and martyrs, continuing abroad that old Tikhonian canonical path of its initial ten years, which went off to the catacombs there from the day Metropolitan Sergii fell.

The Independence of the Bishops’ Synod

The part of the Local Russian Church which is abroad, precisely as its part, is indisputably and unchangeably within it and is in full canonical communion with the entire Church Universal. In its administrative structure, as part of a local autocephalous church, it obeys the directives of its All-Russian Church Authority, starting from November 7/20, 1920.

The rights of the Bishops’ Synod arose, as a phenomenon of the internal church life of the Russian Orthodox Church, first in Russia, as the Supreme Church Authority, and then continued abroad, existing independently of the will and consent of any local church. The recognition of the jurisdiction of the Bishops’ Synod alongside the jurisdiction of these churches is required only on the territories of local churches. Russian bishops could perform any administrative or liturgical acts only with the consent of these patriarchates, and so they actually existed there. It follows from this that outside these patriarchates they perform liturgical and administrative acts without their consent, defense, and supervision, as soon as there are Russian parishes in these places.

There were in old Russia, with the consent of the Holy Synod, metochions in the Churches of the Greek Patriarchates, and in their course our missions and churches were in Jerusalem and other patriarchates with their consent, but in their own jurisdictions. The right to have its own missions and churches outside the territory of local churches was realized by the Russian Church as it was by other churches, without anyone’s consent in America, Japan, China, and Europe. In connection with civilian events of recent times the properties of the Russian Church have only expanded abroad, having obtained temporary unification next to foreign church authorities until they are united with the Russian authority,

The Serbian Church, recognizing the authority of the Bishops’ Council and Synod over all dioceses, missions, and churches outside Russia attributed its own significance to this authority, independent from its being in Serbia. Chairman of the Bishops’ Council and Synod Metropolitan Anastasii spoke about this 8n 1927: “Neither the Council nor the Synod are bound by territory. Should it happen that the Synod cannot fulfill its functions in Serbia, it will move to France, Germany, England, China, or into some other nation. The Council can gather in any country that way as well.”

The Antiochian and Bulgarian Churches have unfailingly displayed the same signs of recognition, love, and helpfulness as did the Serbian Church. From the other churches attitudes were changeable. They would be good, changing to the worse under various influences, and again becoming good.

The claims of Constantinople. Of course, we would be unlikely to expect all local churches to go in step with the Serbian Church, maintaining the interests of their Russian sister without self-interest, especially on the part of the Constantinople Church. Due to its primacy and chairmanship among all it bears the ecumenical title. With the downfall of the guiding role of the Russian Church the Ecumenical Patriarchs felt themselves to be successors to its ecclesiastical authority and world influence, especially since the expulsion of all Christians from Turkish Asia, when the patriarch was barely able to hold on in Constantinople with a few small dioceses. It could fix its position only by extending its power mostly onto the part of the Russian Church that is abroad. Taking into account the tasks of the Bishops’ Synod we will understand to what degree its existence was sometimes inappropriate for the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

In 1922 Constantinople established its exarchate in Europe, headed by the Metropolitan of Thyateria and announced, through decrees of March 16 and April 27, 1923 and June 28, 1924, that Metropolitan Evlogii of the Western European Churches was uncanonical and had no right to rule those churches, and also stated that the Russian Church cannot have churches under its submission outside the limits of its nation, and all churches in Japan, China, and other places must submit to him. The Synod and the metropolitan challenged these claims in a series of letters.

In June 1923 the Patriarch of Constantinople broke directly into the confines of the Russian Church and placed under his submission the Russian Diocese of Finland as an autonomous church. Leaving Patriarch Tikhon’s protests and those of the ruling Russian bishop in December 1923 without consequences he consecrated uncanonically the genuine pseudo-bishop German Aava to please the Finnish government.

In 1924, at the hardest moment in the life of the Russian Church, when one could have counted on the help of the senior hierarch of the Ecumenical Church, the Constantinople Patriarchate, influenced by the Bolsheviks and renovationists, displayed hostile actions toward the Russian Church. It recognized the condemnation of the patriarch by a renovationist council, sought his removal, urging Patriarch Tikhon to renounce his authority and abolish the patriarchate, and intended to send an investigative committee into Russia. The patriarch sent a special message rejecting such unlawful interference in the affairs of the Russian Autocephalous Church.

Concurrently and under the same influence, the Constantinople Patriarchate demanded that two Russian archbishops in Constantinople transfer into its jurisdiction and cease commemorating Patriarch Tikhon and being under the Bishops’ Synod. The Patriarch of Serbia refused this and the Patriarch of Antioch categorically condemned such interference as being without foundation and deplorable.

In November 1924 the autocephaly of the Polish Church was recognized, whereby it was fully placed into the power of its government, Orthodoxy’s enemy. This violation of the rights of the Russian Church was categorically condemned by Patriarch Tikhon.

Metropolitan Antonii, Chairman of the Bishops’ Synod, after defending the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1923 from being expelled from Constantinople and emphasizing to the president of the Lausanne Conference the significance of that patriarchate for Orthodoxy, was obliged to send a mournful message on February 4/17, 1925 to Constantinople Patriarch Constantine VI using the following expressions: “Until now I have been raising my voice only to glorify the Ecumenical Patriarchs, however I am not a papist and I remember that besides the great bishops there have been many heretics, anathematized together with Pope Honorius. And now the same path of disobedience to the Church was taken by Patriarchs Meletios and Gregory VII, who have picked out the Polish and Finnish Dioceses without the consent of the All-Russian Patriarch out of a wish to please heterodox governments. Metropolitan Antonii asked them to give up their claims to the borderlands that were seized from the Russian Patriarchate.

But Patriarch Basil III explained that all Orthodox immigrants who live outside their Mother Churches must be under the Constantinople throne.

And Patriarch Photius II accepted into his jurisdiction the Western European Diocese, which was part of the Petrograd Diocese, attaining what was striven for in 1922.

And finally, in May 1936 the Patriarch of Constantinople accepted into his jurisdiction the Russian Diocese in Latvia in the same unlawful way and placed Metropolitan Augustin there.

In 1937 he placed a bishop for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in America.

At the same time, he displayed his acquisitive strivings toward the diaspora of the Serbian Church in various countries. He proclaimed Mount Athos to be the exclusive property of the Greek Church and barred Slavic monks from going there, bringing their monasteries to decline, liquidation, and seizure by the Greeks.

Taking advantage of the difficult situation of the Russian Church the Constantinople Patriarchate allowed itself to interfere in its matters and border, without having any canonical basis for this. His reference to a canon (Chalcedon 28), according to which “bishops in barbarian lands” obey him, that is those who establish new churches outside the Byzantine Empire, but in the provinces of Pontus, Asia, and Thrace, which were no longer subject to this patriarchate. All autocephalous churches have this right to have missions outside their boundaries that are subject to them. But the canons forbid a bishop to “extend his authority to another diocese, which previously and from the beginning was not under his or his predecessors’ authority (Ephesus 8). For when were Finland, Poland, Estonia, or Latvia, or the parishes of Western Europe, under the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople? And when did bishops of his jurisdiction establish new churches in these “barbarian lands”? Isn’t the Patriarchate seizing inheritance belonging to others which had never belonged to him? Such Greek papism and imperialism of Constantinople violates the very core and joy of the true structure of the Ecumenical Church as a brotherly and apostolic union of different and freely self-ruling local churches.

The same canon speaks about this: “May the arrogance of worldly power not creep in under the guise of a religious rite, and may we not imperceptibly lose, little by little, that freedom that the Lord gave us with His blood.”

The normal situation — The Moscow Patriarchate was powerless to fight against such interference, being held captive itself, a situation from which other naturally flee. In place of the All-Russian Church Authority its temporary representative, the Bishops’ Council and Synod steadfastly defended the heritage and rights of the Russian Church all these years.

Autocephalous churches have always and everywhere had the right and duty to have missions outside their boundaries and in those of other autocephalous churches, and to assign their bishops there, and this right has never been taken away from them for the benefit of any other church. The Russian diocese and parishes in Europe, America, China, and Japan have never been under any other, and were always subject to the Russian Synod.

And lately, having been isolated by circumstances of war and revolution from its Mother Church, its parts that are abroad must remain within it and cannot submit to other patriarchates arbitrarily or also arbitrarily establish autonomies and autocephalies.

And other local churches and Eastern Patriarchates cannot lay claim to the inheritance of the autocephalous Russian Church.

Such is the canonical and indisputable foundation, casting away any anarchy and lawlessness, of the existence of the part of the Russian Church that is abroad, which has its episcopate here, in order to realize in its council the general episcopal authority and to lawfully assume the head of this special portion of the Russian Church until the onset of normal times and canonical structure in it, for which it is likewise fighting.

In order not to err against the holy canons the Eastern Patriarchs nor only cannot lay claim to the Russian inheritance or accept it in subjection without the consent of the Russian Church, but they cannot take any side in that internal canonical dispute which the latter might have. The holy canons and past bitter experience with renovationism forewarn against such interference. Patriarchs can be mistaken in evaluating Russian ecclesiastical events.

The final judgment over its affairs belongs to the local Russian Church itself.

The relation of the eastern patriarchs to the contemporary Moscow Patriarchate is a relation of equality and even seniority, and requires nothing of them. Without any other head of the Russian Church they deal with this one. And in recognizing it at a trial over it they can participate in a similar way, having been invited for it by the local Russian Church. Such is the law of autocephaly.

However, the presence of a canonical dispute between Russians suggests at least caution to the eastern patriarchs, and they cannot use their authority to force any part of the Russian Church to submit to the current Moscow Patriarchate, as it happened in 1945 in Jerusalem in connection with the Russian Spiritual Mission.

The part of the Russian Church that is abroad has a firm basis to claim that the current Moscow Patriarchate is an uncanonical establishment that does not represent the Russian Church, that unworthily occupies a place among the canonical heads of all Orthodox local churches, and will inevitably lose it according to the coming judgment of the Free Russian Local Council.

Attitudes and politics are changeable. At present the Constantinople has lost part its unlawful acquisitions (Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic) unexpectedly, by the Soviet occupation of these areas. In the future it might reexamine and correct its principled positions for the triumph of peace, order, and love in the Universal Church.

10. Exarchates and Autonomies

While faithfulness to the Russian Church for its part that is abroad lies in remaining within it but in refraining from becoming subject to the current uncanonical Patriarchate until the Russian Church receives freedom and a normal life, unfaithfulness to it, presupposing purely logically, could be expressed in three possible courses:

1) Going into the jurisdiction of another local church

2) Separating from the Russian Church by autocephaly or autonomy

3) Submitting to the Sergian Patriarchate

All of these courses have been realized in practice.

The course of the Bishops’ Synod is unprecedented and foundational, while the development of other currents could occur only through schism, through separation from it. The Synod cannot be accused of schism, since there was no one for it to separate from, and, most importantly, it did not betray itself, its initial course, in order to become a reason for schism and to yield its primacy to others.

Incidentally, a certain higher pattern inevitably arises here, as well as a certain parallel. The Orthodox Ecumenical Church cannot be accused of schism, as the local Roman Church is trying to do. It has changed the eighth section of the Creed, introducing the filioque and violating the equality of the persons of the Holy Trinity, and the ninth section, allowing papal primacy to violate the equality of the first bishops of all of the self-ruling local churches that stand in brotherly apostolic union at the head of the one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. The papist Church betrayed Orthodoxy, brought into it what it did not know, and yet it accuses the Orthodox Church of schism, casting blame from an ailing head to a healthy one.

Thus, in this case, the position of the Bishops’ Synod with respect to schisms turned out to be profitable and true in principle as being true to itself and the Russian Church, while the schisms condemned themselves by their history.

The Constantinople Exarchate

The former Western European Diocese of the jurisdiction of the Russian Bishops’ Council and Synod Abroad is now in the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople, who has been successful here in the role of his numerous claims.

This diocese has followed a tortuous path. It was under the Russian Church Abroad from October 1, 1920 until July 16, 1926. Then it was under Patriarch Sergii’s Moscow Patriarchate from August 1927 to October 1930, and under the Constantinople Patriarchate from February 17, 1931. Then again it was under the Moscow Patriarchate from September 11, 1945, and, finally, it was under the Constantinople Patriarchate from March 6, 1947. Thus, the diocese took its fifth position only recently.

In the concluding stage of the Civil War, in February 1920, the future helmsman of the diocese, Archbishop Evlogii, was already in Serbia, and from there, after a trip to Europe at the request of the Supreme Church Authority in Southern Russia, asked through Archbishop Dimitri of Tauride, the Supreme Church Authority to assign him to the Western European Diocese. He was assigned on October 1, 1920 as temporary administrator of these churches of the Petrograd Diocese. However, the rector of the Paris embassy church, Fr. I. Smirnov, wished to have confirmation of this assignment from the central Russian Church authorities, and it was received at the intercession of the Finnish archbishop. The Patriarchal Synod in Moscow, under Metropolitan Evsevii’s chairmanship, recognized the legality of the actions of the Supreme Church Authority and referred to Metropolitan Evlogii’s appointment in the following words: “In view of the ruling made by the Supreme Church Authority Abroad the Russian Churches in Western Europe are to be regarded as being temporarily administered by His Eminence Evlogii.”

In May 1922 the Patriarchal Synod and Council, shutting down the Supreme Church Authority Abroad, said in the decree, by the way, the following: “Taking into account that the appointment by that same authority of His Eminence Metropolitan Evlogii as administrator of the Russian Orthodox churches abroad, no sphere remains for the Supreme Church Authority for its activity. Therefore, the aforesaid Supreme Church Authority is hereby abolished, with Metropolitan Evlogii remaining temporary administrator of Russian parishes abroad. He is charged with presenting ideas regarding the order of administrating the aforesaid parishes.”

Thus, the Patriarchal authority assumed that it was eliminating the authority abroad not just because of its political statements, but also because it was not needed, since it had no sphere for its activity. Therefore, Metropolitan Evlogii’s rights that were previously recognized covered administrative rights even without expanding them, and remained as before. Patriarch Tikhon’s administration did not know that there were nine dioceses under the authority abroad with twelve ruling and vicar bishops.

It is natural that Metropolitan Evlogii, with the presence of the Bishops’ Council, could seek “ideas regarding the order of administering” only from it, especially since at that point the Patriarch was arrested in Russia and was acting according to the decree of November 7/20, 1920. And wherever connection with the center has been lost, according to the decree the diocesan bishop is to immediately get in touch with bishops of neighboring dioceses in order to organize the highest level of church authority. And only if this is impossible does the “diocesan bishop take upon himself the fulness of authority” (November 7/20, 1920, decree no. 362). The most favorable conditions for self-rule and the lawful organization of church authority turned out to be abroad, and Evlogii could not act otherwise than to seek the decisions of the Bishops’ Council.

In connection with this act, Metropolitan Evlogii gave the Bishops’ Council a memorandum saying “I propose the immediate shutdown of the aforesaid authority and for all Russian bishops abroad to immediately start organizing a new central body of supreme church authority abroad, or to restore the old one that was in effect before the Karlovci Council.” Along with the Council he accepted the new basis for the organization of the Bishops’ Synod and signed a circular announcement to thar effect on August 31/September 13, 1922. After that he had occasion to refer to this 1920 decree as valid.

On July 3/16 of that same year Metropolitan Evlogii wrote to Metropolitan Antonii, “It was undoubtedly issued under Bolshevik pressure.” And he wrote in 1925, “I do not recognize any necessary power behind this document, even if it was written and signed by the Patriarch. This document has a political character, not an ecclesiastical one. It has no significance outside the borders of the Soviet nation for no one and nowhere.” And in a message to his flock on June 23/July 6, 1924, he was proving the canonicity of the authority of the Council and Synod Abroad.

However, the temptation of personal power may have appeared for Metropolitan Evlogii already at the final meeting of the Supreme Church Authority to discuss its abolition on August 29/September 11, 1922, when one Bishop (Veniamin) insisted on “the transfer of the fulness of supreme church authority” to himself. Twelve votes, including that of Metropolitan Evlogii, were opposed to this. But still, from that moment on, Metropolitan Evlogii started striving toward the determination and intensification of his rights and privileges.

Beginning in 1922 Metropolitan Evlogii, without the Synod’s knowledge, was sending reports, memorandums, and proposals, directed against Metropolitan Antonii and the Bishops’ Synod, either through Athens and Vienna, or through Finland. In January 1924 he was asking Patriarch Tikhon, through the archbishop of Finland, about abolishing the Bishops’ Synod and confirming his rights. He also asked for the Jerusalem Spiritual Mission to be transferred to his diocese. He asked the same of Metropolitan Peter in 1925. But the patriarch left all of the numerous submissions by Metropolitan Evlogii without consequences, although it was known that he provided receipts for these papers. The Synod would hear about this correspondence, but Metropolitan Evlogii would deny this at meetings of the Council and Synod.

In the Synod Metropolitan Evlogii systematically maintained his particular opinion. Having received his diocese from his fellow brethren he strove his hardest to rule it without the Council and the Synod, to expand his rights and, creating a dyarchy, introduced chaos into Church life. The Bishops’ Council, wishing to set limits to these bids for power, accepted his plan for the Western European Metropolitan District, giving him what was almost autonomy.

But Metropolitan Evlogii allowed himself to intrude upon the sphere of other church bodies and diocesan hierarchs, With Metropolitan Antonii’s blessing a church community was started in Australia and was included in the jurisdiction of the Bishops’ Synod. Metropolitan Evlogii intruded there, and the same happened with Paraguay and Uruguay. Finland had been an autonomous diocese since 1918. Metropolitan Evlogii allowed his own parishes to be started there without the consent of the ruling bishop and called upon the Finnish flock to submit to pseudo-Bishop German on February 12, 1926, who was categorically rejected by Patriarch Tikhon and the Russian episcopate on December 28, 1923 and October 27, 1925. And it should be added that the renovationist “metropolitan” Vasilii Smelov, who had fled from Russia to Persia with his wife and two daughters, and was rejected there by the archimandrite of the Russian Spiritual Mission of the Bishops’ Synod, was received by Metropolitan Evlogii with no questions asked on October 22, 1933, no. 1891, with an assignment to “start the task of setting up the Church of Christ in faraway Persia.” as if there hadn’t been a Russian Orthodox parish there until then.

He was constantly in touch with organs and official figures who were subject to the Bishops’ Synod and other ruling diocesan hierarchs without their knowledge. He would issue church messages as the head of the Church Abroad without having the authority to do so, and not being recognized as such by the episcopate. He would give orders affecting the entire Church without obtaining consent from the Supreme Church Authority of the Bishops’ Council and Synod.

By the rights of the Supreme Church Authority, which had appointed Metropolitan Evlogii to a part of the Petrograd Diocese and formed a metropolitanate out of it, the Bishop’s Synod found it necessary, for the Church’s benefit, to separate six parishes in Germany out of that diocese into an independent diocese, which gave cause for Metropolitan Evlogii to break away from the Bishops’ Council.

Patriarch Tikhon’s decree expanding the rights of vicar bishops was unceremoniously disregarded by Metropolitan Evlogii, and when the Bishops’ Synod demanded its fulfillment, Metropolitan Evlogii in an official letter refused to publish and fulfill it. This gave final impetus for the Bishops’ Council to free up the German vicariate with its Bishop Tikhon from Metropolitan Evlogii’s rule as despotic.

On June 16/29, 1926 Metropolitan Evlogii left a meeting of the Bishops’ Council because it refused to examine this issue as the first item.

A bishop’s departure from obedience to the Bishops’ Synod simply because it made a decision he didn’t like is an unacceptable route toward church anarchy, an undisciplined and uncanonical act.

Then Metropolitan Evlogii started an argument about the Synod’s powers and finally stated his secret thoughts, whose realization he had been striving for the past four years. “On April 22/May 5, 1922, after the Patriarch condemned the Karlovci Council,” he said, “my church powers were not only confirmed, but significantly strengthened and expanded. I was directed to close down the Church Authority Abroad that was in Karlovci, take control of all the Russian churches, and to present my ideas on how to administer them. This decree essentially gave me all of the power over Russian Orthodox churches abroad.”

In further polemics Metropolitan Evlogii presented himself of equal status with the Council on November 26, 1926, to which the chairman of the Synod, Metropolitan Antonii, replied, “The Bishops’ Synod regards your statement that you regard yourself and the Bishops’ Council to be of equal status as blasphemous. Not only any of the hierarchs, but even the Patriarch, cannot hold a position equal to the Bishops’ Council.” (Tserkovnye vedomosti, January 1-15, 1927)

The purpose of the Bishops; Council, which was openly confessed from the beginning is the unification of all dioceses and spiritual missions abroad into a single entity, (Message of August 27, 1927) That is why it is the Bishops’ Council Abroad. Metropolitan Evlogii on his part found it necessary to “limit the unlawful, in his opinion, claims of the Karlovci Synod to seize the entire fulness of church power over the whole Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.” (Tserkovnyi vestnik,6-7, 1930) In the name of what? In his name, his own personal claims, which he regarded to be lawful, supposedly according to the exact sense of the 1922 decree. He said that “The attempt to cast out of historical circulation the 1922 Moscow decree, which is clear and is not subject to any misinterpretation, simply because it is not to someone’s liking, is arbitrary and unlawful.” (Address of August 6, 1926) But are the attempt to cast out of historical circulation the presence of an entire council of bishops abroad, the law of the same Moscow Patriarchate, which was being implemented due to existing conditions, the uncanonical motives of the shutting down of the Supreme Church Authority, the notorious violence of the Bolsheviks and the Patriarch’s captivity, whose decrees therefore lost all juridical power and authority, and, finally the undoubted lack of understanding by the Moscow Patriarchate of the situation abroad lawful and arbitrary? Why would that be? Well, because it was pleasant for just one bishop and supposedly gave him the opportunity to stand alone in opposition to the entire Council even after four years. Thus, independently of words and verbal reassurances, Metropolitan Evlogii actually rejected the canonical principle of conciliarity, regarding himself equal to the Bishops’ Council and destroyed church authority. But this is not at all a dispute between different sides but disobedience by one of the hierarchs of the Bishops’ Council, as a church authority. (Bishops’ Synod’s Definition of November 25-26, 1926.)

Regarding his departure from the Council Metropolitan Antonii wrote to Metropolitan Evlogii, “You tried to justify your departure from the Council in every possible way, but this is not the first time that you are resorting to such means of influencing the Council. This happened at the 1922, 1923, and 1924 Councils, and was your practice in Russia” (August 17-30, no. 1001). These are interesting facts to characterize the personality.

Having left the Bishops’ Council in June of 1926 Metropolitan Evlogii, in step with his previous activities, hurried to anticipate events. A week before the act separating the German Diocese from the Metropolitanate was published and received he sent out circulars to German parishes regarding disobedience to the Synod. However, on August 4/17 he suddenly sent a written declaration recognizing the canonical judicial and administrative power of the Bishops’ Council and delegating two vicar bishops to resolve disagreement, with an expression of regret for leaving the Council. But without waiting for a reply and the Council’s decision he brought consternation to it and the delegates by issuing on August 6/19 a message to the flock, affirming his exclusive rights and in attacks insulting to the Synod entirely annulled his recent steps toward peace. Following this, still not receiving a reply from the Synod, he hastily went to Germany, visiting German parishes and trying to rouse them against the Supreme Church Authority.

With the exception of two or three of his vicar bishops, Metropolitan Evlogii had no supporters among the overwhelming majority in the Bishops’ Council (35 in all). The hierarchs remaining in their sees were respected by their flocks, but also respected in their brotherly union of bishops. From them he had unanimous rejection, since they could perfectly discern his psychology and understood the true spirit of his power seeking, knowing his mode of operation. Thus, it remained for Metropolitan Evlogii to rely only on the respect of his flock. Only agitation could accomplish its recognition and affirmation of his special privileges.

Messages to the flock, student gatherings, a series of deanery meetings, clergy and laity drawn into the dispute between hierarchs, an intelligentsia ignorant about church canons, lectures, the acceptance and encouragement of addresses, a press pouring tubs of dirt, slander, lies, insinuations — everything in the Western European Diocese was set in motion against the Bishops’ Synod. The leaders of student other organizations named Metropolitan Evlogii a confessor, sufferer, and head of the Church Abroad, although not a single bishop of that church regarded him as such. Metropolitan Evlogii did not protest. He himself fired up church unrest, inciting the clergy and the flock to disobey the Synod, fighting for his personal power and influence against the institution which stood in the way of his ambitious thoughts. His falling away from the Bishops’ Council that he had previously recognized and his open rebellion speak for themselves. And he convicted himself by all of his contradictory actions, arbitrariness, diplomacy, and cunning.

He arbitrarily removed Bishop Tikhon, whom the Council had appointed, from his duties and took it upon himself to forbid him from serving. Only the Council can do this, and Metropolitan Evlogii himself demanded an ecclesiastical trial over the American “church rebels” Bishops Alexander and Stephan and Metropolitan Platon (letters to Metropolitan Antonii of December 14, 1922 and February 11, 1923). At that time he forbade Priest Znosko along with the Council, but now he took it upon himself to allow Archpriest Prozorov to serve, who had been forbidden by the Council. The only power that is canonical for such actions no longer existed for him. After proclaiming himself to be equal to the Council he had actually become a thief of general episcopal power.

He had previously opposed the subjection of the part of the Russian Church that was abroad to other local churches, but now he became with definite purposes in favor of the subjection of those who are in the territories of these churches. Already after the Supreme Church Authority was shut down he responded to the claims of the Ecumenical Patriarch in 1923 and 1924 (March 28, no. 352 and July 10, no. 978) by defending the Bishops’ Synod, and he wrote the following: “All of these churches become Russian metochions at the present time within the new Orthodox Church in Czechoslovakia, and their situation is identical to that of the Russian Spiritual Mission with its churches in Palestine, and also to the current situation of the churches in Constantinople, Serbia, and other Orthodox countries.” Now he was advocating the independence of those Russian parishes that are only outside those countries, such as, for instance, his parishes, while recommending that parishes directly subject to the Bishops’ Synod and located mostly in the territory of other local churches, become subject to those churches. Thus, his purpose is to destroy the Synod’s significance along with the destruction of his own central diocese. He was shamed only by Serbia, which with its authority and defense supports the Bishops’ Synod, for otherwise he would not have taken it into account for a single day, without giving it its own central and uniting significance for the Church that is abroad, but would have fully attempted to concentrate it around himself. He wished to please Serbia and other local churches, sacrificing Russian parishes to them, only to deal a blow to the Synod and raise his significance. He was now for breaking up the part of the Russian Chruch that was abroad into numerous independent organisms in order to pick them into his jurisdiction part by part, according to his prior method.

The polemics between the Bishops Synod and Metropolitan Evlogii lasted seven months with acute experiences, at least for the Western European Diocese, and on January 13/26, 1927 the Bishops’ Synod ruled that Metropolitan Evlogii was to be brought to trial by the Council and removed from ruling the diocese. Another bishop would be appointed, and he would be forbidden from serving (Circular Message no. 114, of January 22/February 4, 1927).

The Bishops’ Synod cannot be accused of hasty action, insufficient patience, excessive strictness, or of unfulfillment of a duty or a striving toward schism. Much valor was needed not to yield once again to Metropolitan Evlogii and to resolve to censure him, and to endure the loss of a large diocese and grief from Parisian unruliness.

The Bishops’ Council had over twenty instances of Metropolitan Evlogii’s despotism and disobedience. The truth may not be understood, but it must be fulfilled in the expectation of the future judgment of history which is fuller and unbiased.

Thus, the cause of the schism here was the ruling of the Russian Patriarchal administration, which was unlawful in its motives. Erroneous, compromising, and brought about by Bolshevik violence, the actions of the Patriarchate resulted in the same consequences here as well as in Russia. And the temptation of power appeared here for one bishop with disparagement of the Council’s power.

The censure by that Bishops’ Council, to which the bishop in question himself belonged, and which he left out of his self-will, have insuperable canonical force, besides just repentance and a return to obedience. Other bishops cannot accept him without the consent of the first ones. In order to hold on to any portion or form of canonical church existence Metropolitan Evlogii naturally rushed to be defended by the heads of other local churches. In the spring of 1926 he was not yet thinking of the possibility of such an appeal and wrote to Metropolitan Dionisii of Warsaw on May 5 /26 (no. 736, Voskresnye chteniia, no. 74): “I regard the appeal to the Patriarch of Constantinople and his participation in this matter (presumably for organizing the Orthodox Church in Poland), and with all my deep respect to the lofty position of this Orthodox hierarch, as incorrect, and I see in this action, which is not justified by the canons, interference with the internal matters of the Autocephalous Russian Church.”

The Ecumenical Patriarch, who in 1923-24 proclaimed Metropolitan Evlogii to be uncanonical and didn’t commemorate his title, was now (on June 18, 1927), encouraging him and condemning the Synod’s actions. The Patriarch of Alexandria, formerly Ecumenical, and the Metropolitan of Greece likewise issued such messages (in April and May), guided by political influences and also being at odds with the unifying idea of the Russian Church Abroad.

But the path that Metropolitan Evlogii chose was dangerous for him. While the Bishops’ Synod declared that the abolition of the Supreme Church Authority was unlawful and dictated by Bolshevik forcefulness, he focused his attention on his privileges received upon this abolition and was naturally forced to dismiss thoughts of forcefulness by the godless and recognize this action as a matter of the free volition of the Moscow Patriarchate, affirm his subjection to it, and from then on to deny the Synod’s right to rely on the 1920 decree. This reliance on the power of the Moscow Church and the “behests of Patriarch Tikhon,” which are now mentioned continually, was, of course, insincere, and came with the secret hope that this power would actually not be realized and remain as fiction, but only in order to be freed of the Bishops’ Synod and expand his own privileges. However, he earnestly proceeded to affirm his new canonical basis, which in his opinion was unassailable and unique, and dug a hole for himself into which he fell with extraordinary effect.

The first subjection to Moscow. When Metropolitan Evlogii was writing on June 5/18, 1927 to his flock, “We wish to remain faithful to the end not in words but in deed, to the behests of our father, the Holy Confessor Patriarch Tikhon… we will obediently fulfill the wishes of his lawful successors” (Tserkovnyi vestnik, no. 1), Metropolitan Sergii was preparing his declaration of July16/29 in Russia. Two weeks earlier, before it was issued on July 1/14, he sent Decree 93 to Metropolitan Evlogii proposing that he and all archpastors and pastors abroad provide a signature of loyalty to the Soviet Union. Those refusing to do so would be discharged from the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate. The leader of the Western European Diocese was now receiving confirmation of his privileges under conditions what were too difficult, but he had no place to go. He himself and his vicar bishops sent a refusal to make “political statements” to Moscow, pastors’ statements were “being kept in his office,” and lists of all the clergy who complied with these obligations were likewise sent to Moscow (Metropolitan Sergii, December 1927, Terkovnyi vestnik for April 1931).

He himself pictured his flock’s mood this way: “A general negative attitude is being created not only to the person of Metropolitan Sergii, but also to his case.” And later he described it to Metropolitan Sergii in the following words: “You don’t know what agitation and what indignation was evoked by your request that I and my clergy express loyalty to the Soviet regime… It took great effort on my part to relieve that agitation” (October 27, 1927 and July 8, 1930). But the question is, for what and for whom was this subjection to Moscow and this moral forcefulness over the conscience of pastors and the flock, who, according to their emigré nature were opposed to the Soviet regime? Absolutely for no one in the entire emigration, except for Metropolitan Evlogii, who now needed to fix his uncanonical situation (that of Metropolitan Sergii as well, it should be noted), and in practice to justify this already taken false position. Trouble incited him when he broke with the Bishops’ Synod, setting off completely along the mistaken path, for one mistake gave birth to another.