From ROCOR Studies

I don’t know how many interviews I have managed to conduct, starting with my first one in 1991. And they were all of the differing quality. I feel that the transcription of the interview of Maria Reshetnikova with Vladyka Lavr which I am presenting for your attention is successful primarily because it presents an opportunity to travel in time. Supplemented by the author’s helpful comments the interview allows us to join them in the no longer existing part of the print shop where I happened to have worked for ten years. The interview comes in three parts: Christmas with Vladyka Lavr, About the Church in Russia, and M. M. Zarechniak’s Reminiscences of Vladyka Lavr. A Russian brochure containing all three parts of this trilogy can be ordered in color on silk paper by going to blurb.com/b/9680830.

Deacon Andrei Psarev,

October 20, 2019, Jordanville, NY

From the author

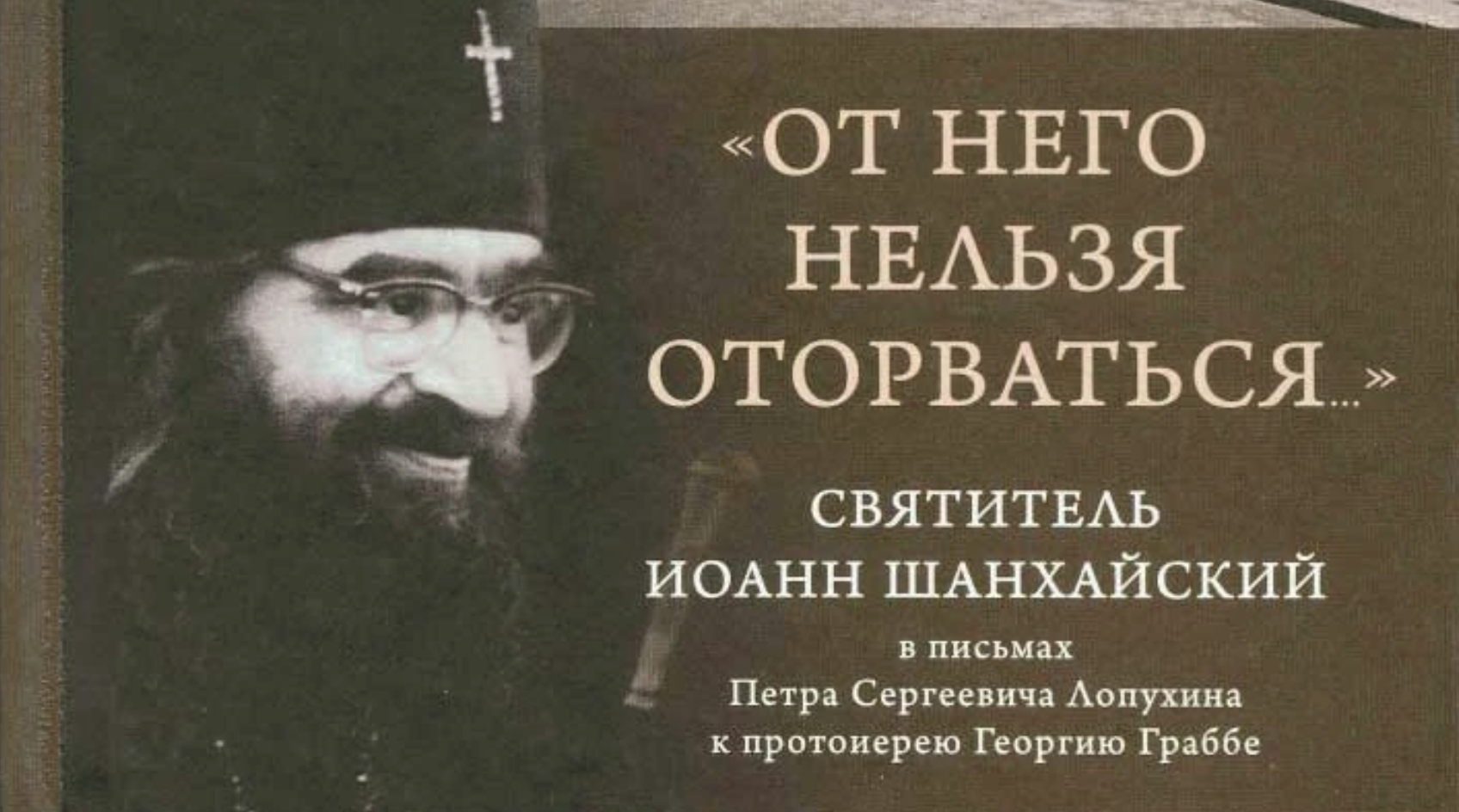

Metropolitan Lavr (Shkurla) became the fifth First Hierarch of the Russian Church Outside Russia in October 2001. He began his life journey practically as an orphan in the small Carpathian village of Ladomirova, where the Orthodox Faith was returning in the 1920s, counter to all the prohibitions by local authorities. The monks of the Pochaev Brotherhood, fleeing from the terrors of Communism, erected their monastery in this Slovak village and set up their publishing business, for which they had been known for years, in 1934. The Lord brought twelve-year-old motherless Vasia Shkurla, who was living in the same village, to the monastery, and from that moment on the destinies of the publishing Brotherhood of St. Job of Pochaev and the future Metropolitan Lavr merged into one. Together they experienced parting with their native land, traversing the roads of war, and in the foreign land of America, they created anew the age-old principal mission of the Pochaev Brotherhood – publishing and education. Thousands of copies of service books, writings of the Holy Fathers, and spiritual, historical, and autobiographical literature, as well as editions of periodicals on the spiritual life of the Russian Orthodox diaspora with a similar circulation, were disseminated throughout the Orthodox world. But they were especially awaited in the Soviet Union, where at times even functioning churches lacked spiritual literature. Before long a seminary opened up at the monastery, and a brotherhood started growing, in which countless spiritual giants of the Russian diaspora would take part. But it was precisely for Vladyka Lavr, once a village boy from a poor Carpatho-Russian family, that our Lord had prepared a great historic mission – to become head of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia and bring about its unification with the Moscow Patriarchate in 2007. The liturgical relations among the Orthodox, which had been disrupted by the atheistic regime for almost an entire century, were reestablished. “Most of all, beware of quarrels, forgive each other when you are offended,” wrote St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, citing Holy Scripture. “Keep in mind that whoever quarrels pleases the Devil, while whoever reconciles others assists Christ and will be received in the Heavenly Kingdom as a son of God.” (Mt. 5:9) These words can be also ascribed to Metropolitan Lavr, who devoted so much of his spiritual strength to the reunification of churches. My documentary film and this printed interview are a humble mite toward honoring the blessed memory of Metropolitan Lavr.

The Trip to Jordanville

Having received Vladyka Lavr’s blessing to visit the monastery in advance I came to Jordanville along with a cameraman on Christmas Eve itself! On the way to Holy Trinity Monastery, which is located next to the small town of Jordanville, a five-hour drive from Manhattan toward Canada, we went past places that were not only historic but also symbolic in their significance for America. The first battles of the American Revolution took place here, near the town of Utica. We stopped the car and even took photos of a national memorial that announced that the Oriskany Battle was the bloodiest battle of the American Revolution. A small unit of militiamen living in this colony of England fought here in 1777 for their independence from the British Empire. In spite of great losses the Americans were victorious, foiling the English plan to invade New York with the aim of cutting off New England from the other rebellious colonies. The North American patriots managed to gain a major victory over the Royal Army. “All revolutions are bloody and take away human lives” was what I thought as we passed by these places of past American battles. I know that nothing is accidental for God, and yet it is still amazing that my filming journey, which was devoted to the Bolshevik Revolution and its consequences took me past a route that was sprinkled by the blood of American revolutionaries two centuries before. Suddenly, January snow started pouring down in huge flakes outside the car windows. A snowstorm began as if out of nowhere, and we had to pull over to the side of the road in order to wait through this total whiteout. Everything around us was so covered with snow that the road was not visible through the windshield of our minivan.

I had spent much time preparing for this encounter and was quite worried that it wouldn’t take place. Fortunately, God’s Providence helped me make it to Jordanville in time, and I was able to photograph many interesting and important places in this legendary historic monastery. In the evening of January 6 we set up our camera on the porch of Holy Trinity Church, and finding ourselves almost under the cupola we could preserve for posterity the whole magnificence of the festal service on the Eve of Christ’s Nativity. The faces of the saints and the frescos of magical splendor by the legendary iconographer Father Kiprian beautifying the cathedral walls appeared especially festive in the luster of Christmas candles. Vladyka Lavr led the service, accompanied by a choir composed of seminarians and monks.

The service ended close to midnight, and on the morning of January 7 Holy Trinity Church was already filled with Orthodox people who, living in America, continue to maintain age-old traditions. Entire families had come to celebrate Christmas – mothers in festive dresses, fathers in austere suits, children in traditional Russia costumes… After the bells rang everyone was invited for the Christmas meal. In spite of being very busy and tired from numerous services and extending hospitality in those distant Christmas days of 2004 Vladyka Lavr found time for a detailed discussion and gave Orthodox viewers of future generations priceless reminiscences about historic events. His blessing to create our film allowed me to preserve for future generations the multifaceted and diverse life of the monastery, and to convey the atmosphere of those years when Vladyka Lavr lived and served in Jordanville, an atmosphere that was rosy and filled with events and the expectation of new exciting changes of the post-Soviet period.

Thanks to this rare footage viewers will see what played a key role in the spiritual, scholarly, and educational mission of Jordanville. They will see the enormous collection of a historical archive and a most extensive library which have preserved essential evidence of the life of the White emigration. There are the priceless exhibits of the monastery’s historical museum, which can only be visited with a blessing. Its depositories contain countless medals and award crosses of the officers of the Imperial Army, personal items that belonged to the Royal Martyrs, ancient icons, old paintings, centuries-old liturgical items, and hundred-year-old clergy vestments. And, of course, there is the legendary print shop, which for over half a century has been producing books, magazines, and even color icons for the Orthodox of the whole world – and all this is the work of the Jordanville brethren, including Vladyka Lavr himself, who had been the irreplaceable editor of many Orthodox publications and has many years of experience working the printing press, having from his earliest childhood assisted the printing Brotherhood of St. Job of Pochaev with the publication of religious literature back when he was living in Ladomirova. It is hard to believe but true that this varied literature was produced for a long time on just one printing press. Now the refectory is where the print shop used to be, and many books and magazines can be found on the internet and in bookstores all over the world. The brotherhood continues publishing books, which, as a rule, get printed in Russia. Many years have passed since those shoots in Jordanville, so that the footage from now distant 2004 looks even more valuable, with joyous Lyovushka, the monastery “blessed one,” still young at 86, standing next to the Christmas tree, while on the walls and on the press itself we can see the photos of those whose obedience this was. The monks of the brotherhood, who worked here days and nights, kept memories of their teachers and predecessors, who bequeathed to them the primary mission of the Pochaev Brotherhood – the establishment of Orthodoxy, publishing, and education, which they have borne throughout the years, in spite of wars and persecution, since the thirteenth century!

Here in Jordanville, one forgets that our native land is on the other side of the globe. Nature itself around the monastery helps the viewer to be immersed into the festive atmosphere. Winter in these parts is intensely cold. Everything was draped white with snow during these Christmas days. Pure magic!

Jordanville. January 7, 2004. 3 p.m.

The Monastery Print Shop

Besides the cameraman and myself, seminarians and novices came into the print shop, as many of them had grown up under Vladyka Lavr and of course, listened to their abba’s stories with interest. Legendary Lyovushka, that touching large child of Jordanville, also came to hear the story of his childhood friend. Much of what Vladyka was telling, Lev Ivanovich knew well.

The interview in the print shop took about two hours. During this time Vladyka Lavr gave details of his childhood in Slovakia and of the arrival there of the printing Brotherhood of St. Job of Pochaev, which became a real adoptive family for him. He told us about the tragic lot of the Orthodox who had lived for centuries under the oppression of Catholic Uniates and likewise shared priceless reminiscences of many historic events of which he became a witness. In the second part, we had the honor of hearing his opinion of the historic reunification of the Church Abroad with the Moscow Patriarchate after an almost century-old separation, which was then only being prepared.

Walking up to the bookshelves at the very end of the large print shop room Vladyka Lavr sits in an armchair and, glancing cheerfully at the cameraman, asks:

─ What are you, servant of God? Where are you from?

─ From Odessa

─ Ah… Odessa ─ mama!

I come up to Vladyka to prepare him for the video camera recording.

─ May I attach this microphone?

He points to the battery.

─ And what’s this?

─ That’s to make the sound better.

─ So you’ll tape me? We don’t know what you’ll be up to over there (laughing). So, how can I help you?

─ Vladyka Lavr, I know that you’re very busy. I’d like to thank you for this interview and to remind you that I was brought to you at Novo-Diveevo, at the centennial of St. Seraphim of Sarov, and that I gave you a cassette and a letter. Have you had time to look at that?

─ I haven’t looked at the film, but I did look at the brochures and icons. I sent some of it to Russia. Icons are requested in Russia, so I send many small icons to those who request them.

─ This film is devoted to the entire generation of Russians who were practically ejected out of the country after the 1917 Revolution – officers under Wrangel, cadets, Cossacks, clergy, their descendants, and so on. We always ask all of our heroes, including you, to tell us about their lives. We have much less time available than usual. Tell us how your family emigrated. I know that you’re off the Yugoslav emigration. Tell us about your father, your family, about your fate.

─ I will correct you right now.

─ Correct me, of course.

─ Don’t record me for now, servant of God ─ Vladyka says to the cameraman, who doesn’t turn off the camera. Aware of this, he continues talking.

─ In the first place, if I am in the emigration, my ancestors are from St. Vladimir’s “emigration.”

He is distracted for a second to help give a chair to the cameraman.

─ There, look, take one from there.

─ Why can’t this be recorded?

─ Why no, I’ll explain it a little for now.

I think that Vladyka Lavr has nobly spared by illiteracy.

─ Here, take any chair.

Vladyka again turns to the cameraman, concerned that he is still standing behind the camera. Having made sure that the cameraman is finally sitting on a chair, he continues his story.

─ I’m not an emigre, and I’m not from the old emigration. I’m a native-born Carpatho-Russian. I was born in the Carpathian Mountains to the most ancient Orthodox branch, the Calabido Slavs. My ancestors had lived there, probably from the time of the Vladimir-Volynsky Princedom, perhaps even from the time of St. Vladimir – from those times, I don’t remember exactly. The Vladimir-Volynsky Princedom was great there, in this part of Western Rus. All this was part of that, including Lemko territory. We also had a prince named Laborec, and there’s a town by that name. This is ancient history, and I’m simply reminiscing. I don’t remember the exact details, I won’t give you the years, it needs to be looked up somewhere. I happen to be Carpatho-Russian. If you wish to record this, you can

─ Yes, we are recording, I said, since we, fortunately, didn’t stop recording.

─ I’m descended from Carpatho-Russians I was born in Ladomirova in the Carpathians, next to the town of Svindik. Next to it is Presov, which is a large town, sixty kilometers away. That’s my homeland, that’s where my ancestors were born and where they lived.

Working on this text, I saw that according to current maps the distance between Presov and Svidnik is actually about 60 kilometers. This seemingly insignificant detail is evidence of Vladyka’s unusual memory and his attention even to seeming trifles.

─ What year were you born?

─ I was born in 1928, on January 1. I just turned 76.

─ Happy birthday!

─ I’m a new calendarist by birth, but an old calendarist according to Orthodoxy, after my connection with the monastery. During the First World War and afterward, when the Revolution happened in Russia, Russia was devastated. But this part of Carpathian Rus’ was under Austria for several centuries, and later under Austro-Hungary, in the last period. All Carpatho-Russians lived with the hope that Russia would come at some point and free the Russians.

In 1848, when there was a rebellion in Austria, the Hungarians rose up. Unfortunately, — that’s what we say, of course, that this was unfortunate, monarchists, perhaps, don’t feel that way – Russia under Nicholas I sent its troops to crush the rebellion. And many protested against the Austrian yoke – during this time rebellions started in Hungary – but Austria again continued oppressing Slavs, Russians, Carpatho-Russians, Serbs. In that period there were also other ethnic groups – Lemkos, Moldavia, partly Poland, and so on. Everyone was waiting for some kind of relief, some kind of change. Then the First World War came. Everyone thought that now the Russians would come. The Russians did come into those parts and started liberating and invading them, but later, through God’s will, of course, this didn’t come about. Russia didn’t stay there. Finally, Russia almost won the World War, but “thanks” to the fact that the European fellowship was against Russia everything collapsed and a revolution was created in Russia. And so this revolution tore everything down and emigres went to various countries, among which, after the First World War, was our Carpathian Rus’. The Carpathians turned out to be under Czechoslovakia, which included the Czech land, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Rus’ Subcarpathian Rus’ was not able to obtain any kind of autonomy, but there was still unrest among the people, who had been upset since the start of the War. Could we have a little break?

Vladyka Lavr addresses the cameraman, and we stop the interview, but the camera is still on. Vladyka turns to me, concerned, I believe, about the length of the history lesson I was being given.

─ Is this too much?

Obviously, this wasn’t “too much” for me, and I continued, happy about the opportunity to question Vladyka further.

─ Tell us, in what immediate situation did your family find itself?

Reigning in my youthful curiosity and ardor, Vladyka sets me at ease.

─ I’ll tell you right now.

In walks in a person in a cassock, and Vladyka turns to him.

─ You want to listen? This is my godson, whom I baptized long ago, I don’t remember what year that was.

Vladyka’s “godson” gives a smile.

─ In 1961.

─ Oh, that was so long ago.

─ They told me you were the new abbot.

Interrupting the “break” he had announced, Vladyka continues with his story.

A reception in the abbot’s office on the day of Nativity

─ And so, the First World War ended in such a way that Austro-Hungary was divided up, but still continued its existence. Hungary became a full-fledged nation, and then there were Czechoslovakia and Carpathian Rus’. My parents found themselves in Carpathian Rus’. During this period, and even earlier, during the First World War, there was a rather strong movement to return to the Orthodox Faith. The entire region where I was born was under the Unia. The Uniates follow the Eastern Orthodox rite. Their ritual is Orthodox, but their hierarchy, bishops, priests, and clergy are connected to Rome. That’s why it’s called the Unia. That’s a whole history – the Union of Brest, the Carpatho-Russian Unia. During the First World War, there was a strong movement to return to roots, as they now say in Russia, to Orthodoxy. In the sixteen and seventeen hundreds there was Orthodoxy in our parts, the villages were Orthodox, the priests were Orthodox, but when there were no more Orthodox bishops, the clergy started gradually dying off. Thus the clergy and all who were with them gradually became Uniate under Austro-Hungary automatically. And then, those Russophiles who were for Russia appeared during the war, and the Austro-Hungarian police would keep watch and arrest them. In the first instance, they persecuted and then executed up to 97 Lemko priests in our parts simply because they were Russophiles, but these were Uniate priests! They served according to the Russian Eastern rite and commemorated the Pope, but because they apparently – and the “apparently” was never proved – sympathized with Russia, were awaiting Russia, that during the war Russia would come and they would unite to Russia. For this, they were executed, hung on telephone poles along the road. They executed their own!

At these words, Vladyka Lavr raises his hands, and I hear the anxiety in his voice for the first time.

─ Various Russian activists were persecuted as well and many were executed. But one way or another such a movement did come about. And by 1924 in Ladomirova, the village where I was born in the Carpathians, in the Presov region, there was a strike and a rejection of the Uniate priest – “we want an Orthodox one,” they said.

─ And did your parents have the same attitude?

─ My parents were born later, but my grandfather did. My father and mother were born Uniate, but I was already Orthodox.

─ They had the same attitude of returning to their roots?

─ Oh yes, they had the same attitude, of course. And they were waiting for the Russians, they thought the Russians would come, those who were… but I’ll touch upon this question a little later… So here’s what kind of mood developed. At that time this Uniate priest was kicked out of our village. The women took him and brought him out of the church by force and threw fresh eggs at him, saying “go wherever you like, we don’t need you,” and they were left without a priest. At that time certain peasants were so active that they went to the Serbian Orthodox Church and said that they needed a priest. Please give us a priest who speaks and understands Russian and Carpatho-Russian. In general, Carpatho-Russian is a kind of Malo-Russian language, not quite Ukrainian, which already had a great number of artificial words, while Carpatho-Russian is a simpler and purer language containing a mixture of languages – Polish, Slovak, and Russian, with Slavic roots.

─ May I ask something? Forgive my illiteracy, but you mentioned Lemkos. What group is this? And what are Hutzuls?

─ These were also nearby, both the Hutzuls and Lemkos. There are various names there, all the way to Moldavia. These was called zhupas, or small government regions, or districts. They are different, their speech changes a bit. For example, we call a potato “bandurka,” while they call it “barabulia” and others call it “pomdetere.” (He smiles) Or no, that’s “potato” in French.

─ So when Hutzuls are regarded as being derived from Ukrainians, is that incorrect?

─ They’re all one nationality, but they lived in different areas, different neighborhoods, and they lived under different influences. They were under somewhat different influences, but we are all brethren and sisters. So this is how we look at this. I must now make a proviso that maybe someone listening to this may not appreciate. Our Carpatho-Russians, unfortunately, — that’s me saying “unfortunately,” perhaps it’s not unfortunate – do not like being called Ukrainians. And ever since they were annexed to us, that is Carpathian Rus’ to Ukraine, they’ve been saying “We’re not Ukrainians, we’re Carpatho-Russians.” This is how they want to be called, it’s the general attitude.

─ That’s interesting!

─ So the village remained without a priest and went to the Serbian authorities, because under Austro-Hungary this church territory was under the Serbian Patriarch in an ecclesiastic sense, and all of the Orthodox had to submit to him. Now Fr. Vitalii, our Vladyka Archbishop Vitalii (Maximenko), happened to be in Serbia at the time. This was not my predecessor Metropolitan Vitalii (First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, Metropolitan Vitalii [Ustinov] – editor’s note). He’s sick right now, but it was another Vladyka Vitalii, who did his best to enable this monastery to exist here in Jordanville. He started the monastery over there, in the Carpathian Mountains, in Ladomirova, as an archimandrite. He was sent there from Belgrade in Serbia, and he started an Orthodox mission in Ladomirova Village, which later became the Brotherhood of St. Job of Pochaev. This was a printing brotherhood, which is what we are continuing here now, and at the same time it was a missionary, for the purpose of spreading Orthodoxy among the Carpatho-Russians. Fr. Vitalii took this on. People started coming to him, and the brotherhood started growing little by little. Publishing started already in 1925. In 1926 and 1927 conditions were quite primitive. A church was built there in the village and was consecrated. People gathered and started publishing a newspaper entitled Pravoslavnaia Karpatskaia Rus’. Now it’s simply Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia] for all Russians. We changed its title. We are continuing it here, this newspaper is already 80 years old.

─ Was this taking place in 1928?

─ Yes, I was just born, on January 1.

─ And so, there was no Bolshevikck power such as in Russia?

─ Bolshevik power came into the world there only in 1948, after the Second World War. And at the time there was the Czechoslovak Republic, as they called it themselves, and were proud of this accomplishment. But the Czechs weren’t particularly kind to the Carpatho-Russians. There was supposed to be a republic like in the Soviets, so there were three parts: the Czechs, Slovaks, and Rusyns. But the Rusyns, they said, were simple and semi-literate, which meant that they took the back seat.

Saying this Vladyka Lavr gesticulates to show how Rusyns were regarded at the time – “in the back seat.”

─ So how did the Carpatho-Russians regard these terrible changes which were taking place in the Russian Empire at the time? I have the Revolution in mind. How was that regarded?

─ At the time, of course, the Carpatho-Russians didn’t know much. And, in general, little was known abroad about what was going on in Russia. Just a few things barely made it through the iron curtain, especially in the twenties and thirties. We had very faint and contradictory information… I’m afraid I’ll wear you out with my stories.

─ No, in no way will you wear me out… Unless you’ll wear yourself out!

─ All right, that’s fine… Let me figure out where I stopped.

─ You stopped with Fr. Vitalii being sent for the rebirth of Orthodoxy.

─ Yes, Fr. Vitalli started this mission, and it gradually started functioning. If I try to give all the details, I simply won’t remember them right now, and it won’t go smoothly. It’s simply hard to imagine the meagerness in which this was when it got started. In spite of this, these people would come, some didn’t make it and left, while others stayed, and the mission started functioning and becoming more firmly established. There was a missionary school, there were clergy, students were being prepared for church work, then priests were ordained and these people began to spread Orthodoxy. We’ll touch upon the issue of Orthodoxy after the Second World War in a few minutes. So this is how this undertaking started growing. I repeat, there were terrible poverty and difficulties. Help came from certain Carpatho-Russians who were living here, in the United States. Many Carpatho-Russians had relatives here who had left Austro-Hungary before the First World War at the beginning of the twentieth century and even earlier for earnings in other countries, mostly in the United States. My grandparents on my mother’s side were here in America for a while and returned later, dying back home. My father’s brother and three sisters were here in America. His brother returned home and died there, while his sisters and their families are here. And that’s how it was with many. People went here and managed to accumulate some funds that they sent there. So Father Archimandrite Vitalii was helped in this way. His situation improved and he would give out many books and brochures of a churchly and na-tio-nal, purely Russian national nature.

Vladyka Lavr distinctly enunciated the word “national” by syllables. Apparently, it was very important for him that Carpatho-Russians were returning to their national and religious roots.

─ We used primitive methods for our work. I don’t know how familiar you are with publishing, but I’ll give you an example. The printing press there – what kind of press did we, did Fr. Vitalii have? And in general, such presses existed there and in other places.

Vladyka Lavr picked up a sheet of paper and explained:

─ Let’s say that this the case. It’s divided up by barriers, like this and that. The whole alphabet goes in here, all the letters, with each letter having its own section. There are many such cases, depending on the typeface. Let’s say we had the Latvian typeface, which was bought in Latvia and has its own design, so we called it Latvian. There was another one, boldface – you know that one?

─ Well, I understand that there are typefaces of different styles and sizes.

─ Yes, different styles. And so, you had to take each letter and put it in such a…

Vladyka stopped for a minute and pointed to Lyovushka, his longtime friend Lev Ivanovich Pavlinets, well known to anyone who had been to Jordanville at least once for his wit and tendency toward foolishness. Lyovushka, as everyone at the monastery fondly called him, had known Vladyka Lavr well from his early years, long before their arrival to America.

─ Lev Ivanovich was there already, but he wasn’t working there at the time… And so you take each letter… Here’s the word “Vasilii”, “V”, “a”, “s”, “I”, “l”, “I”, “I”… and you keep on composing like that. You compose one line, then another, a third one, a fifth one… Once you’ve composed ten you take it out and set it. And you do this page by page. This is very slow and time-consuming work. But the most tedious work comes later. The case is done, which means that this style of typeface is finished, that it all has been set. That means this has to be printed, and once that’s done, it needs to be sorted out! It needs to be laid out there letter by letter. That’s the most tedious work – and also the most boring. Your hands are soaked in kerosene, and there’s the smell!

Vladyka brings his hands to his face, smiles merrily, shows by gestures how the case was sorted out, and, preoccupied with youthful memories, doesn’t notice his microphone coming off. As I reattach the microphone, he continues talking animatedly.

─ You get all dirty, and the kerosene gives you a headache. The kerosene washes the paint away so the letters can be separated, otherwise, the paint holds them together. So that’s what the work was like. But in spite of that we worked and published church literature as much as we could. At that time nothing was being printed anywhere. Before the Second World War Russia was cut off from any church production. All of this had been available in Russia earlier, and we could get some items from the Uniates in Lvov, in Poland, but we weren’t interested in getting them from someone else, we still wished to have our own Orthodox items. We printed what we could and distributed it for the Russian emigration, and for Carpathian Rus’, which had returned to Orthodoxy at that point. Village after village gradually returned, churches started being built again, and by the Second World War there were already quite a few Orthodox there.

─ Did the Second World War impact your region?

─ The Second World War – I’ll tell you right now how all this happened, and then we’ll touch upon the events after the war, all right? But let us rest up a bit. I’m sure that the servant of God is tired, his arms will start hurting.

Vladyka is again concerned about the cameraman, who says, “It’s all right, I’m used to it.”

And then Vladyka, smoothing out his beard, asks me,

─ And where are you from? From what place?

At that point, one of the seminarians offers Vladyka Lavr water or soda, and he answers:

─ Yes, bring me a little water or some soda from upstairs. I don’t drink Coca-Cola, some kind of ginger ale would be better.

Pointing to the cameraman and me, he says,

─ And bring some for them, too.

And, abruptly returning right away to the interrupted conversation, he unexpectedly asks me.

─ Where were you born?

─ I’m from Moscow.

─ From Moscow, yes? You were probably born just recently, ten or twenty years ago?

Vladyka is joking. Surprised by such a compliment, I ask again,

─ Me? No, I’m 33.

─ Well, that’s a bit more… thirty-three. Sure, that’s also not so much, of course. I think that everyone remembers how war was, how the bombs were coming down, how everything was rumbling overhead, how you had to hide. Maybe you read or heard about this, but didn’t experience it. That means a lot, since it’s one thing to experience it and another to hear and read about

Vladyka becomes thoughtful, repeating “good, good,” trying to figure out where to take the discussion, and then asks me:

─ So you’re from Moscow? Where did you live there? In what part of Moscow?

Quite surprised by his knowledge of Moscow districts, I answer:

─ Generally, in Novye Cheryomushki. That’s a new district called Novye Cheryomushki.

─ Cheryomushki…

Vladyka Lavr’s interest was aroused. I try to return the conversation to his life.

─ But your story interests me more. All that furtive activity…

Vladyka smiles, squinting, and interrupts me.

─ But I’m also interested in Moscow, since I’ve been to Moscow.

I laugh and try to return to the previous subject.

─ We’ll talk about me later!.. About all that furtive activity to reestablish Orthodoxy, was it halted in some way during the Second World War? Did the war get in your way?

─ I believe it did, of course, since we had to get out. And I’ll tell you why we did. We had to drop everything and move out, but then we got here, and so we’ve been here 56 years already.

─ Let’s do this gradually. In what year did you leave?

─ I’ll tell you right now. They’re about to bring us a little water. I ask your forgiveness!

─ All right, then you can question me now.

I give up and ask the cameraman to turn the camera off, so as not to waste the film on me. Now, after so many years, I regret this decision, since I would have liked to hear all of the details of this conversation, in which Vladyka Lavr questioned me about my childhood in the Soviet Union, my parents, how I came to America, how I decided to become a journalist, and why I got interested in the history of Orthodoxy and the emigration. The seminarian was taking a long time to get the drinks, and as he waited Vladyka Lavr turned this necessitated break into a warm discussion in which my searching questions were turned into his questions about me, my generation, the home I had left behind in faraway Russia… Everything was interesting and important to him. Considering his power of observation and intuitiveness, I believe that he sensed my feelings of nostalgia and homesickness. The powerful feeling of nostalgia, which was tearing my heart apart, especially in those years, moved and directed many of my life decisions at the time, including, of course, the work on my project about the history of emigration and the reason for my visit to Jordanville. I missed home and was looking for a place of consolation in a foreign land. Vladyka Lavr saw this, he sensed it and gave me an opportunity to pour my heart out. He switched the discussion to me tactfully and cautiously… He heard me out, took everything into account, and, looking at me with his penetrating and wise gaze, said,

I give up and ask the cameraman to turn the camera off, so as not to waste the film on me. Now, after so many years, I regret this decision, since I would have liked to hear all of the details of this conversation, in which Vladyka Lavr questioned me about my childhood in the Soviet Union, my parents, how I came to America, how I decided to become a journalist, and why I got interested in the history of Orthodoxy and the emigration. The seminarian was taking a long time to get the drinks, and as he waited Vladyka Lavr turned this necessitated break into a warm discussion in which my searching questions were turned into his questions about me, my generation, the home I had left behind in faraway Russia… Everything was interesting and important to him. Considering his power of observation and intuitiveness, I believe that he sensed my feelings of nostalgia and homesickness. The powerful feeling of nostalgia, which was tearing my heart apart, especially in those years, moved and directed many of my life decisions at the time, including, of course, the work on my project about the history of emigration and the reason for my visit to Jordanville. I missed home and was looking for a place of consolation in a foreign land. Vladyka Lavr saw this, he sensed it and gave me an opportunity to pour my heart out. He switched the discussion to me tactfully and cautiously… He heard me out, took everything into account, and, looking at me with his penetrating and wise gaze, said,

─ All right, where did we stop?

─ At the Second World War and how you decided to leave and why.

─ Ladomirova had a mission created by Father Vitalii, who was later here at Jordanville as archbishop. I repeat myself in order to clarify. Vladyka Vitalii, who was Father Vitalii back then in 1934, was called to Belgrade by Vladyka Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) in our church headquarters, was consecrated bishop, and was sent to the United States. In 1934 Vladyka came to New York and found out that there was a small monastic community in Jordanville, consisting of Archimandrite Panteleimon, Father Yakov, and with him was his fellow brother, Fr. Iosif, who joined a little later, and even later came Fr. Pavel. They created this monastery, bought this farm, and acquired a small parcel of land and a little house as well. They built a small house and church, but all of this burned down. Further over there in the monastery there’s a white house on that spot.

Right during the filming of our discussion in the print shop where we had gathered for the conversation a whole procession containing seminarians and several small children walked in with a Christmas star, singing “Christ is born, glorify Him…” The cameraman didn’t turn off the camera and everything that took place was recorded. During the singing of the Nativity hymns Vladyka Lavr rose and attentively listened to the seminarians’ choir. He patted the children on their heads and when the seminarians finished singing thanked everyone and promised to definitely give Christmas candy to the children who took part in this performance. “Christ is born, glorify Him!” everyone exclaimed and left the print shop. But as soon as we got set to renew our discussion a tall man appeared whom no one knew. Vladyka Lavr asked him, “Who are you?” The man didn’t speak Russian and, embarrassed by the fact that Vladyka noticed him and stopped the interview, responded in English: “Forgive me, Vladyka Lavr, I didn’t want to bother you. Merry Christmas to you!” “Thank you, and the same to you!” Vladyka responded in English to the unfamiliar American. It turned out that one of the little boys who had sung the Nativity hymns with the seminarians was this American’s son, and the man wished to receive the Metropolitan’s blessing for the boy and take a photo as a keepsake. I cannot recall that during this whole time of spontaneous visits to Vladyka Lavr anyone ever reported anything to him, asking his permission in advance. Everything took place simply, I would even say informally, and there was nothing for me and the cameraman to do other than to wait for everyone who wanted to see Vladyka Lavr and get his blessing on this holiday. The camera kept on filming everything that was taking place, and so even now, so many years after the fact, we can see this living evidence of Metropolitan Lavr’s kindness and accessibility, his openness to all who came to him and whom he often didn’t know, who wished to receive his blessing or photo as a keepsake. The American understood that he caught the right moment and without further ado called his son and offered the seven year-old to sit on Vladyka’s lap and have their photo taken. Without any change in his expression Vladyka, in no way embarrassed by this unexpected suggestion, asked the American in English: “Is this your son?” “Yes, this my angel Gabriel” the proud father responded, looking at his son with pleasure as he sat in Vladyka Lavr’s lap and found himself to be the center of attention of the film crew and everyone who was present that evening at the filming of the Christmas discussion with the Metropolitan. All that time the boy wasn’t shy before the camera, while Vladyka patted him on the head and instructed him in English, and the American took his photo, not at all uncomfortable about interrupting the filming. “Well, Gabriel,” Vladyka Lavr smiled, “look at your father in the close-up.” This unexpected photoshoot finally ended and we returned to our interrupted discussion. The boy accidentally knocked the microphone off Vladyka’s cassock, and we had to readjust the sound. During this whole time, Vladyka’s longtime friend Lyovushka remained among the monks and seminarians who were present at the discussion. As a child, having apparently wearied of the long silence, he started making wisecracks and giving advice. “Be quiet, Lyovushka! Don’t bother us,” Vladyka Lavr asked him nicely, like he would a disobedient brother. It was already late. The long Christmas day was coming to an end and tables set for the celebration were awaiting many. I was hoping that nothing else would interrupt our discussion and we could successfully complete the filming since another such unique opportunity might never present itself. In spite of being tired, Vladyka Lavr gathered his thoughts and continued our discussion.

─ The war began in Europe. At first the Germans started “establishing order,” first in Yugoslavia and then in Greece. Greece capitulated. Troops came through Slovakia, right past us, through Ladomirova. I don’t know how much you can imagine the geography, but there you have the Dukel Pass. Older people in the Soviet Union would have known that. It was known as the Dukel Pass during the war. That’s one of the main passes from Europe through the Carpathian Mountains into the Carpathian Valley on the other side, and then you can go in any direction, either toward Lvov, or Poland, or Lutsk, or Kiev – toward Crimea, as we would say in the Carpathians – and then further on along Russia. And so, in 1940 or 1941, I was twelve or thirteen then, for of course I don’t remember exactly, troop movements began. German troops went all over. At that time Slovakia went into a pact with Germany, and they became partners. And the Germans subjected the Czech land, making it a protectorate. Slovakia had its autonomy, they could be in charge themselves, live their lives, and do what they wanted, but the Germans were there and used everything they needed, controlling transportation, and so on. For this, they fixed our road, made it new, and along came cavalry, infantry, tanks…

─ Certain emigres whom I interviewed earlier and who lived through this period of the Second World War in those areas of Eastern Europe told me that they had seen peaceful populations welcoming the Germans with bread and salt. Do you recall such incidents?

─ Well, we didn’t especially welcome them with bread and salt, they simply went through Slovakia as if it was their own land, and kept going on. Over there, in Russia, perhaps, but I was never there at the time.

─ But what was your attitude toward the Germans?

─ Well, we had no particular attitudes, no prejudices, I’d say, as much as I can remember. There were some partisan attitudes, with someone hiding in the woods and attacking the Germans. Help was given to Russian refugees, those from Russia, who escaped from German war prisoner camps. They came individually, but they did escape. And they would hide in our monastery in Ladomirova, where we would give them shelter. It wasn’t that we were hiding them, but in any case we didn’t hand them over, and if they were living with us, they would help out a bit, do some work, and would then go off. We would help the Russians, of course, so that they wouldn’t get into the Germans’ hands. We’d help them. Sometimes we would take someone to another village, putting him into a cart, covering him up with hay, and transporting him that way so that he could leave and hide, avoiding getting caught by the Germans. He would be brought to a village that was almost under no control. The Polish border was nearby, which meant that the military border was there as well, where the front was advancing, and, of course, you had to be cautious there. That was the way we helped Russians, as much as we could, at any rate, and through them, we also found out about certain things that were going on in Russia, what the attitudes were and so on, because, I repeat, we had not had any particular contacts before that. And it was that way until 1944, that’s how we lived there. First, the front got started in 1941 and the war expanded gradually. On the feast day of All Saints Who Had Shone Forth in the Russian Land, war was declared and there they went… You could hear the cannonade. The front began fifty kilometers from us, and then there was very rapid movement and you couldn’t hear anything anymore. The German advance started, and war prisoners appeared. At the approach of 1944, the situation went into reverse and the Germans started retreating from Russia. And we could see that if we stayed we’d be in trouble, of course.

At this point, surprised, I asked him “Why?” I was struck by Vladyka Lavr’s open-heartedness and humility in regarding his dangerous activity of hiding and rescuing Soviet war prisoners as any kind of heroism. “Nothing special” was how he spoke of the courageous actions of the monastery brethren at Ladomirova, explaining that he was only twelve when the Germans came and Soviet war prisoners had to be hidden within the monastery walls and then taken, hidden in a hay-covered cart, to safe territory in neighboring villages, farther away from the Germans. Considering how the monks risked their lives by helping Soviet war prisoners, it was hard to listen to Vladyka Lavr’s further account of his forced parting from the beloved monastery not due to the Germans but to the Soviet forces approaching Slovakia.

─ But why? Weren’t you looking forward to Russia’s coming so much? Sorry for misspeaking, I understand that my question isn’t a simple one.

─ The local residents were looking forward to that, but we weren’t looking forward to the Communists’ arrival. We were waiting for Russians, not Communists. And the people who were waiting for Russians there thought that these would be the Russians who came in 1917 and 1918. Those came and got busy, helping people, restoring their houses, and so on. But the ones who came weren’t the same Russians. Once they came, the Slovaks and later the Czechs as well had such an attitude toward Russians that oho!.. not a word, and they’re ready to stab you in the back!

At these words Lyovushka of childlike directness, who had been closely listening to Vladyka, laughed nervously, exclaiming “oy, yoy yoy!” Yes, it was strange to hear such admissions from kind and smiling Metropolitan Lavr, but, apparently, such was the bitter truth of the horrible Second World War and its consequences. The complex political interrelationships between various nationalities taking part in the war and passionately rejecting the Communist regime as well as Fascism often remain unnoticed. However, it was precisely in Eastern Europe that these interrelationships turned out to be more intensely strained. It suffices to recall the Russian Protective Corps in Yugoslavia which fought against Tito’s Communists and the Soviet invaders, as they were regarded at the time. This was a complicated page of Russian history, which was Russian because the Russian Corps was founded by White émigrés. And although there was not a single battle between them and the Soviet Army, seventeen thousand Russian officers of the former Imperial Army and very young representatives of the White emigration who had come out of cadet corps and Russian Orthodox gymnasiums and were already born in Yugoslavia after the Bolshevik Revolution fought against their “fellow countrymen”, Yugoslav Communists, and were ready to take up arms against their ideological enemies, the Soviet Army. It is gratifying to know that God did not allow a repeat of brotherly bloodshed in the forties. Why, for many on both sides of the ideological barricades the memories of the horrors of the Civil War of 1917 to 1922 were still fresh. However, for Orthodox believers of all European countries the question of “whose side are you on” was inevitable, and many were prepared to pay for their Christian choice with their blood. As we know, many did so, accepting a martyr’s death for their faith in God. Such a fearsome choice arose before the monastery brotherhood in Ladomirova as well. Judging from the confidence in Vladyka Lavr’s voice it was clear that even after half a century he had no doubt that there was no other path to salvation for the brethren other than abandoning the monastery that they had worked so hard to build.

─ So listen… ─ says Vladyka Lavra, smiling at my importunate inquiries.

─ It’s still interesting about your father. What was your father’s provenance?

─ My father was a peasant.

─ He wasn’t any kind of noble, and he didn’t take part in any counter-revolutionary actions?

─ There was nothing much for me to be afraid of, but I decided to leave with the brotherhood because, in the first place, I had become accustomed to it, and in the second place I was attached to Vladyka Vitalii, who was already here in America. He baptized me. I don’t remember him baptizing me, but I do remember him visiting from America. I was attached to this Vladyka and wanted to be with him, around him. And, besides, when I was there at the monastery I was sent to school, cared for, and given help, and we wished that I would bring some kind of benefit to the monastery, and I wanted to bring benefit to the monastery as well.

It is not at all easy to pose personal questions in an interview, but I wished to understand how the future Metropolitan of the Russian Church Abroad found himself at a monastery since childhood and how his family let the little boy, whose name in the world was still Vasilii, go down a road full of uncertainty through all of Europe in the grip of war. I had the boldness to ask Vladyka Lavr these questions only during our fifty-minute discussion, realizing that I could reawaken sad recollections in him of parting with his family forever. However, Vladyka’s calm reaction, with no sign of sadness, surprised me. Once again, I was convinced of his special way of conversing, unearthly calmness, and amazing emotional balance, but at the same time there was no sign of coldness or reserve. He was open and even emotional, but also unflaggingly calm, in spite of such distinct recollections from his life which he generously shared with us.

─ Let me ask you this. Whose decision was it to hand you over to the monastery to live and study? Was this your parents’ decision?

─ My father agreed to it, and I made the decision myself. I liked it there, as a boy I served in the altar, went to church there ─ I enjoyed that and wanted to stay.

─ Do you remember the day when you decided that you wouldn’t be living with your family but will go to the monastery? After all, you were a child.

─ I lived on two fronts.

Lyovushka burst out laughing, hearing this well-aimed comment, while Vladyka Lavr continued with a smile.

─ I’d go home and I’d go to the monastery. I’d go to school and also visit home. You see, I was an orphan. My mother died unexpectedly. I was six and a half, and my sister was three. Later, of course, I had a stepmother. Three brethren were from the stepmother, my father had three children from his second marriage. I had no problems at home because I was still little, but I simply came to like it at the monastery. And so we left. We came to Bratislava, where we stayed for half a year. The front was already approaching. There were revolts in Slovakia, first one and then another. The Germans suppressed one of them, but everything was already in turmoil. We had to move further, and on January 5, 1945 we left Slovakia through Dresden and Prague and stopped in Berlin for about a month. There was a bombing. It was there that we experienced a little what bombs were like, for before that we had lived through the war half-starved, things were difficult, but nobody bombed us, nothing like that happened.

─ And did you hear anything about the Russian Liberation Army at the time. I believe that their last location happened to be in Prague?

─ It was later that they ended up in Prague and had to surrender there. That was later… yes. That happened when we were already in Germany, before the actual surrender. We had some connection with them, since we conducted services for them. Our clergy served for them, but we weren’t administratively connected, we simply ministered to the soldiers. For feasts, such as Christmas, we served in one of their camps. I recall a service in a certain place and then in another. I remember that service.

─ Did you see Vlasov himself?

─ I saw Vlasov when we were leaving Berlin. We were in the same train car.

─ You don’t say?!

─ Yes.

─ And where were you going from Berlin?

─ We went to Bavaria from Berlin, and he was also moving there from Berlin, to somewhere in those parts.

─ In the same car?

─ No, not in the same car. We had our own train cars. We knew someone in Bratislava who worked for the railroad, a railroad worker, and he did us a favor and arranged two cars for us. We loaded all kinds of items and supplies in one car, and the other one was for us.

─ Which of the allies helped you make it through your wartime journey?

─ Of the allies, there was Vladyka Vitalii. He would send money for us from here, from America, to Switzerland, where we would get it.

─ So you were a kind of traveling mobile monastery?

Vladyka Lavr smiles at these words and nods in agreement.

─ For half a year, yes… for a year, or a year and a half.

─ So what impression did Vlasov make upon you? I realize that you were a child, but still, these were the final years of his life.

─ Well, you know, I saw something in passing, he went right by us, but I didn’t speak with him, of course. Later I met some of his assistants, but not in person. It was like before ─ I saw them during the church service, but of course, I can’t recall the details. I cannot tell you anything in particular. I can’t tell you anything bad, since I had no interaction with them.

Vladyka Lavr returns to telling about the journey through wartime Europe.

─ At any rate, our waiting for the war’s conclusion ended in May of 1945. This was on the first day of Pascha. Along came the Americans with tanks. We looked, and it was away with fences, they set them on fire. They brought out milk and eggs to treat themselves. The Germans also had that, so they were bringing out their food until the end. The war had apparently ended, but they still were bringing out their food to the stores.

─ You have in mind that the peaceful population kept on bringing food to the front?

─ Why no, they did it simply so that you could buy things in the stores. You would use ration cards. Everything could be bought, except for cigarettes and chocolate. And coffee couldn’t be bought.

─ You said that your monastery conducted services for the members of the Russian Liberation Army, for its officers. But at that time there were many repatriation camps. Did you come across them, across those who were sitting there, awaiting their fate?

Fr. Alexander Kiselev serves moleben at the foundation of the Committee for Liberation of the Nations of Russia. Prague. Nov. 14, 1944

─ Yes, we served for them. Say, if we served near a camp there were people who also came to service. I remember, for instance, that we served in Walshtetten, there was such a place, and a unit of the Russian Liberation Army was there. I don’t know which unit it was, the propaganda unit, I think. Many of them would come to our service and pray. There weren’t that many. The repatriation camps appeared later, and the moods there weren’t particularly pleasant. We were passing one such camp at Biberach, and some girls met us there. They ran up to us and said:

Vladyka Lavr gives a slight smile, mimicking the wrath of the fellow travelers.

─ “Why are you so-and-so’s hanging around here? You need to go to your homeland!” and so on. And we said, “Our homeland is Slovakia!” Well, we squabbled with them a bit over there. And so… they had made up their minds that “we’re going home!” They started walking around in uniforms that were more or less presentable, which they had acquired from somewhere, since they had been workers somewhere, but now it meant that they were no longer obeying the Germans and were preparing for repatriation home.

─ Didn’t it seem strange to you that this Soviet, formerly Russian, Army, which made you leave your native country, and was devoid of Orthodoxy and true Russian traditions, was the one power that pushed you out of your land. And having fled it and ending up abroad you ran across the Russian Liberation Army, where suddenly you encountered among its members those same Russians, that old Russian guard?

─ Well of course, it was strange. The encounter with the youngsters in Biberach was somewhat strange that way when they said, “We’re going home, and where are you going?” Of course, there were people who felt otherwise, since they understood more, they realized the situation better in a practical sense. And those youngsters who found themselves in camps, in difficult circumstances, in trouble, lived in hope, of course. But later they returned to Russia and were all disappointed, of course.

I know one man who went there, to Russia, perhaps in 1963, as a tourist. And so he went with the tourists in Kiev through the caves (most likely, he’s speaking of the God-given Caves of the Kiev Monastery of the Caves – editor’s note). The guide is saying, “give your attention to this and that,” leading everyone and showing everything, and there’s a woman following behind, so that no one wanders off in the caves, since it’s possible to get lost or to hide that way for a while and come out later, so there was monitoring. This woman accompanied them. And so she said quietly to the young man, “I’ve been to Germany.”

While saying this Vladyka Lavr starts whispering, mimicking the Kiev woman. It is known for a fact, especially according to the reminiscences of Fr. Victor Lokhmatov, Vladyka’s cell attendant, who accompanied him on train rides, that he made numerous visits to various cities and holy places in the former Soviet Union. Vladyka conducted his pilgrimages incognito as a simple monk. Knowing about these trips of Vladyka Lavr with the aim of personally observing the life of the Russian people I happened to think that perhaps this “tourist” was Metropolitan Lavr himself? So Vladyka continued in the voice of the Kiev woman.

“I’ve been to Germany and saw plenty there,,, and nowhere, you know… If you see so-and-so convey my regards… this and that…” ─ She requested something ─ “just don’t tell anyone what I told you…” So that was the situation. People were used there, of course. Some were taken somewhere. While others, like let’s say the military, went through what Solzhenitsyn described. They “got theirs” for getting captured over there and so on. Of course, that was difficult to realize. And we, for instance, weren’t in Lienz and didn’t see it.

To my surprise, Vladyka Lavr touches upon the tragedy in the Austrian city of Lienz, where at the end of the Second World War as a result of an international agreement, or more correctly, a conspiracy against the Cossacks fleeing Stalin’s slaughter, thousands of Cossack soldiers and officers, along with their wives and children, were traitorously handed over to be slaughtered by the Soviet authorities. This forced repatriation to the homeland ended tragically. The effort to shove freedom-loving Cossacks into train cars and send them into Stalin’s camps ended with massive suicides of entire Cossack families, mothers threw themselves into the river holding their children, choosing death over slavery in the labor camps. Vladyka Lavr continued:

─ I’ve been to Lienz over the past few years already, simply dropping in there two or three times where all that took place. It was so horrible, so horrible! And Americans were involved there, they bore some guilt, but the British bore the most guilt, since they arranged all of this when they conferred in Yalta with Stalin and, of course, tried to fulfill all of it. And the Russians didn’t want to return to the USSR, they didn’t want that and threw themselves into the river…

Having said that Vladyka Lavr shut his eyes, as if imagining the whole horror of what was taking place.

─ It’s a rapid river there. They just threw themselves upon the rocks… with their children! They jumped out of the train cars… these were suicides… they slit their wrists…

He demonstrated the wrist slitting with his hand. It was clear that he was taking the tragedy of the Cossacks in Lienz very hard. A brief pause ensued after such a heavy account. But again I didn’t notice any anger or bitterness on Metropolitan Lavr’s face toward those he was speaking about. Apparently, he was experiencing it all in his heart, giving a distinct evaluation of the actions of those who were responsible for this tragedy, but there was no anger or bitterness in his voice or on his face. A miracle!

─ Vladyka Lavr, let me return to the chronology of your journey through wartime Europe. In what year did your monastery finally arrive to America?

─ In 1945, in early or middle July, we went from Germany to Switzerland. Vladyka Vitalii arranged visas for everyone from Germany to Switzerland, but we couldn’t go during military action. The Germans wouldn’t give us transit through Germany in order to go to another country. We could enter Germany, and we did, but we couldn’t leave. When the war ended we found the Swiss consul right away and got the visas. We had visas for fourteen, and we used up twelve. We went to Switzerland in June without delay and got there in early July. We stayed in Geneva and awaited the possibility to get to America, but there were problems. We were promised right away that the visas were about to be issued. We came to get them, but someone had sent in a denunciation that we were so-and-so, that we had a gang leader who brought us into Switzerland, and that we were such criminals – and we weren’t being admitted.

Vladyka Lavr gave a barely noticeable smile, straightening out his white beard.

─ It was only on the first of December in 1946 that we arrived here, to Jordanville.

─ What was the first place you came to in America?

─ Well, we landed in New York and went here right away.

─ Understood, to your appointed destination, your home…

Metropolitan Lavr’s Account During the Christmas Dinner at Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville on January 7, 2004.

Vladyka tells the story of the brotherhood’s departure from Slovakia during the festal meal in the monastery refectory

When I had finished working on transcribing the full recording of the interview with Vladyka Lavr, I started working on the film and discovered that within the twelve hours of film taken at the monastery there was a recording of Vladyka Lavr’s account that appears below. In compliance with the established monastery order I ate in the women’s section of the refectory, so I wasn’t present for these reminiscences by Vladyka. His talk was spontaneous, for no one was expecting that he would start sharing his memories of his faraway wartime childhood right at the meal, in the men’s section of the monastery refectory. I was in the women’s section and, unfortunately, didn’t hear anything due to the noise of the many pilgrims, dining in Jordanville on that Christmas Day. However, my film’s cameraman, who was sharing the meal with the monastery brotherhood and seminarians, seeing that Vladyka Lavr had started telling his story, didn’t lose his head, picked up his heavy camera, and, without a tripod and remaining seated on the monastery bench at the dinner table, recorded this wonderful story. Having listened to it after almost fifteen years, I realized that it represents a wonderful addition to the discussion with Vladyka Lavr which I recorded that same day a few hours later

How It Happened.

When, after the festive Nativity service the entire monastery brotherhood, seminarians, and numerous guests and pilgrims of the Jordanville Monastery headed into the refectory to the ringing of bells, they were welcomed by a modest but appetizing and tastily prepared dinner in monastery style.

After the opening prayer, everyone took their seats at the long tables according to the established order. The monks sat on the right side of the refectory, and at the head of this wooden table, there was a place for Metropolitan Lavr. In my three days at the monastery, I didn’t see once ─ and this was confirmed by my cameraman, who partook of the meals with the monastery brotherhood ─ any plates being brought separately to Metropolitan Lavr. His plate contained the same as mine and those of the cameraman, and all of the monks, seminarians, novices, and Jordanville visitors. Having tasted the soup, Vladyka Lavr, without waiting for everyone to finish, and without demanding any special attention to himself or being concerned that most of those present kept on eating, started his narration unannounced. Whoever wished could listen, and whoever was eating kept on eating. As a regular person, I want to become indignant and say, “Stop eating all of you, Vladyka is telling us such interesting stuff.” But that’s my personal reaction, while Vladyka Lavr is not of this world and doesn’t get upset by anything and doesn’t demand anything. With his characteristic humor, he was telling about the complex wartime during which the brotherhood that had left Ladomirova had to survive and preserve itself.

Apparently, Vladyka Lavr started speaking before the cameraman turned on the camera, so my transcription starts in the middle of his sentence. But what he’s saying is so clear that the sentence is understandable even if we don’t hear it all. It’s interesting that in response to my later question in the interview about the meaning of patriotism, Vladyka Lavr repeated his thought. Here is his story word for word:

… Faith will correct the Russian people, if they will live, of course, according to God’s commandments. As Vladyka Vitalii used to say if they live according to the commandments of St. Vladimir, Equal to the Apostles. And then the Russian people and the whole world will embark on the path of correction and turning to God!

At this point Vladyka Lavr pauses to think, as if leafing through the archives of his mind, and continues, recalling life at Ladomirova.

We now are trying to sing according to the rules and canons. Back in the Carpathians in Ladomirova we didn’t have that opportunity. No one knew anything, and there was no one to teach us. We sang in plainchant. In 1942 or 1943 Fr. Antonii (Medvedev), future Bishop of San Francisco came to us in the Carpathians. First he was in Australia, and then in San Francisco (in both cases after the Second World War ─ Dn. A. P.). Thus Vladyka Antonii, when he came to us in Ladomirovo, started inculcating us with knowledge. We didn’t have antiphonal singing. In Serbia they always had antiphonal singing. Over there, if there are two chanters, one sings from the right kliros and the other from the left one.

He smiled good-naturedly, recalling his poor and complicated childhood that was so dear to his heart.

But for us the verses always had to be read out, and so antiphonal singing was introduced. In 1943 Fr. Antonii was trying to have us sing that way, and that got established gradually. Then, in Bratislava in 1944 we were already on the road, since we were fleeing the Communist front that was drawing near. The Bolsheviks were already advancing and were close. Then they went further on into Slovakia and then into central Europe, into Hungary. At the time we were retreating deeper into Slovakia, to Bratislava, and we were there already for the feasts of St. Vladimir and Transfiguration and stayed there till January 5, 1945. On January 5 we boarded a train and headed west through Prague and Dresden, and from Dresden to Berlin. We stayed in Germany for a month. By Great Lent we made it to Bavaria. And the so-called western liberation forces, American and French ones, arrived on the first days of Pascha. The American forces left after two or three days, and the French came in there and, as they say, gave hell to everyone, especially to the poor German families. They would go through everything, seeking various information: “Where’s your husband? Why is he at war?” and so on. German families would even turn to us so that we would intercede for them with the French. We had Archimandrite Kiprian, who was a hieromonk at the time. He knew French, so he spoke with them and softened them up a bit… The war ended and we headed for Switzerland, lived there for almost two years and tried to apply for visas to the United States. We finally received permission at the end of 1946 and came here. There was a house across the street where our seminarians live now, an annex to the right for Vladyka Kiprian, and everything to the left toward the forest was uninhabitable. So we settled in. There was a small chapel. The first room, on the right as you enter was the altar area, and then there was the hallway and another room, where our seminarians study now… We worshipped in the chapel on Christmas of 1946, in 1947 and the beginning of 1948, and in 1949 we started our worship here, in the lower church. We finished building the churches here over the summer of ’47 and ’48.

Vladyka Lavr stops, takes a breath, and, as if responding to a question from someone invisible, explains why he recalled in such detail the arrangement of the rooms at the monastery so many years ago:

Here’s what I’d like to say. In ’49 we celebrated the Nativity in the lower church. Vladyka Vitalii came from New York for vespers and matins. So we’re singing. We get to the ninth ode and conclude with it. Out comes Vladyka Vitalii and starts singing ─ after all, we had to be taught something. He remembered the texts from his studies at the Kazan Academy and could sing them himself, but he couldn’t write down the notes, so then he wrote to Vladyka Ieronim, Archbishop of Detroit, who had been head of the Spiritual Mission in Jerusalem, and he helped us. Later, we got the notes for the Exapostilarion for the Lord’s Baptism, and gradually our singing improved.

The meal was coming to an end and it was apparent that Vladyka Lavr had become engrossed in recollecting those postwar years, when the Ladomirova brotherhood had just come to the forested semi-isolated area around Jordanville. They traversed half of the world to join a small group of monks at Holy Trinity Monastery and, overcoming all difficulties, to build together their spiritual home in a foreign land. As if to explain the importance of what he had related, Vladyka Lavr explained: “I remembered the history of our monastery singing. Vladyka Archbishop Ieornim sent us the notes that we use for singing.” And then he added in a commonplace way, as if shaking off the recollections that had engulfed him, “Right now we’re on our holiday schedule, and tomorrow, with the Lord’s blessing, there’s a festal service at 9 a.m…” The bell rang out abruptly, announcing the meal’s conclusion. Everyone rose up and sang “Thy Nativity, O Christ Our God!” in chorus. At the conclusion, to the greeting by the brethren and seminarians, “Eis Polla Eti Despota,” Metropolitan Lavr, blessing everyone with the sign of the cross, left the refectory and headed for the reception room, where in fifteen minutes everyone who had been in church that morning gathered… Looking at this footage so many years later and listening to Vladyka Lavr’s monastery refectory tale, heretofore unknown to me, I envy myself of fifteen years ago in a good way, for I have these magic two hours of Metropolitan Lavrs reminiscences about his fate and that of those who in the fullest sense replaced his family ─ the Ladomirova brethren… Perhaps someone might find this brief tale to be a not very necessary supplement, but for me, and, I’m certain, for everyone who cherishes the memory of Metropolitan Lavr, any opportunity to hear Vladyka and hear his reminiscences is a joy. Vladyka Lavr himself, judging from the footage in my film, didn’t require any special attention to his reminiscences about the war. He simply shared with everyone who was prepared to listen to them at that Christmas dinner in 2004. And now these reminiscences are more valuable by virtue of being evoked by the memory of his spirit and are told simply and sincerely as if there had not been fifty people in the refectory but one kind longtime acquaintance who understands what a long path the Ladomirova brethren traversed, learning everything anew in the American land ─ the English language, new laws and customs, and even church singing.

Translated by Fr. Alexis (Lisenko)