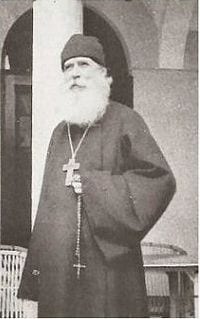

Englishman Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes (1876 – 1953) was a tutor to the children of the martyred Tsar Nicholas II. After the Russian Revolution and Civil War, he went to live in Harbin, Manchuria where, at the age of 58, in 1934 he converted to Orthodox Christianity in the Russian Church. There he became a priest and then in 1936 returned to England. He was assigned as a supernumerary priest to the London parish of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile[1]In the 1930s, what we now call ‘The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia’ was known in the UK variously as the ‘Russian Orthodox Church in Exile’ or the ‘Karlovci Synod’. The church … Continue reading by Metropolitan Seraphim (Lukyanov) of Paris. Late in 1938 Fr Nicholas began to hold services in English at the Russian Church in Buckingham Palace Road. However, early in 1939 he obtained the use of an Anglican church, the Chapel of the Ascension near Marble Arch, for English-language services. For Fr Nicholas the next challenge was to find a choir. Vladimir Rodzianko (later Fr Vladimir and Bishop Basil), who was in England in order to study at London University, introduced Fr Nicholas to Madame Maria Alexeeyvna Nekludova [2]A tribute to Maria Alexeevna Nekludova, compiled by the present writer, may be found here: In Memory of Maria Alexeevna Nekludova. Published on the ROCOR Studies website, April, 2020. … Continue reading who ran a student hostel in Belgrade, Serbia. Maria Alexeevna was able to send to London ten of her students, all daughters of noble Russian families who were living in exile in Serbia. This is the story of those women: how they came to be in England and what happened to them after the outbreak of World War II.

The Arrival of the Belgrade Nightingales

The group of women from Belgrade arrived at Victoria Station, London on 28th April, 1939, where they were met by Fr Nicholas and some of the Anglican nuns who were going to accommodate the visitors. The women had travelled from Belgrade where they lived in student accommodation, known as the ‘Society for the Assistance to Former Pupils of the Kharkov Institute of the Empress Maria Feodorovna’ which was run by Maria Alexeevna Nekludova (1866 – 1948). Many of the residents were orphans. In 1938, Maria Alexeevna made contact with Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes in London and subsequently arranged for 10 of her Russian students to travel to London in order to improve their English and to sing in English in a church choir organized by Fr Nicholas. According to Zina Rohan, daughter of one of the Nightingales (Helen Rodzianko), the introduction came about through Vladimir Rodzianko (later Fr Vladimir and Bishop Basil) who was in England to study. He learned of Fr Nicholas’s need for a choir and he knew that Madame Nekludova was keen to send some of her students to England in order to improve their English. Zina Rohan comments, “It’s anybody’s guess how well they coped with the liturgy in London as the only English words my mother, and quite possibly the other girls, knew were ‘Tveenkle Tveenkle Leetle Starr’.” [3] http://zinarohan.squarespace.com/family-article/ accessed June, 2020.

Chapel of the Ascension, Marble Arch, London, where Fr Nicholas served Divine Liturgy from June until August, 1939, with the Belgrade Nightingales choir singing in English.

The first service in the Chapel of the Ascension held by Fr Nicholas and his choir happened on 23rd April/6th May, 1939, the feast of Saint George. I think this must have been a moleben (service of thanksgiving) because on the next day he wrote to Fr Nicholas Behr in Beckenham, Kent:

So at least there will be regular Orthodox services in English in London. We shall begin with the Liturgy on Sunday mornings at 11 a.m. and gradually increase the services as the Choir becomes more competent. The Evening service at 6.30 p.m. on Saturdays will come next… [4]Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes Archive held by the parish of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, Oxford. St Nicholas Parish Archive (SNPA). In this paper all quotations are from the SNPA archive, … Continue reading

At the beginning of June Fr Nicholas consulted Metropolitan Seraphim about what name the Choir should be given, since it was planned that it would give public concerts. Writing to Fr R M French, Secretary of the Anglican & Eastern Churches Association (A&ECA), Fr Nicholas states,

The Russian name of the Choir [suggested by Metropolitan Seraphim – NM] is literally translated “The Russian Female Church Choir in Memory of the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna,” for short – The Alexandra Choir, but I shall turn this into: “The Russian Church Choir of Female Voices in Memory of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.”

Fr Nicholas goes on to record the fact that the Choir is in London with the help of the A&ECA which was instrumental in obtaining visas for the women. “At the same time, we gratefully accept the Patronage of the A. & E. C. A., how exactly we shall work together, we must discuss, but I don’t think that there should be any difficulty about that…”

An English-language newspaper from Belgrade, the South Slav Herald, in June, 1939, published a full report on the arrival of the Russian women in London:

Belgrade Girls to Sing in London Church[5] Fr Protodeacon Christopher Birchall mentions the choir in his book, Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen (New York, 2014) pp. 283-284. What he writes was based on the recollection of Choir Director … Continue reading

Ten Russian girls from Yugoslavia have arrived in London from Belgrade to live in England for a year in various convents in the London area where they will learn English and acquaint themselves with English life.

A number of them will sing in London churches in a special choir.

This – the first party of Belgrade girls to travel to London under a plan conceived by Dame Maria Nekludova of Belgrade – has been hailed in the London press with great interest. After the initiative of Mdme. Nekludova, arrangements were made for their reception by the Anglican & Eastern Churches Association in London, at the personal intervention of Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes, former tutor to the Russian Imperial Family. The Bishop of London interested himself in the welfare of the girls, and helped in the obtaining of visas for their year’s stay in England.

Originally twelve girls were to have left Belgrade but one girl meantime was married and family illness prevented another from going.

One of the girls is a princess, Irena Sahovskaya, [sic] who will sing soprano in the choir of a West End church (St. Philip’s, Buckingham Palace Road) this summer. Another is Miss Helen Rodzianko, granddaughter of the last President of the Russian “Duma” or parliament…

Queen’s Gift

Queen Maria of Yugoslavia has personally given a donation to the funds for the ten Russian girls, and she is the patron of the Society for the Assistance to Former Pupils of the Kharkov Institute of the Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia, which looks after the daughters of aristocratic families who have taken refuge in Yugoslavia. Many of them are orphans.

The ten Russian girls are delighted to be in London and have already written letters to their “mother”, Dame Maria Nekludova, the 70 years old former Superior of the Smolny Institute in Russia where the daughters of former Russian aristocrats’ families were educated.

Among her former pupils was the present Queen of Italy, then a Montenegrin princess.

Epic Journey

Dame Nekludova brought, single-handed, without funds and almost without food, a body of 157 orphaned Russian girls, pupils of the Kharkov Institute, on an epic journey from South Russia to Bulgaria and eventually Yugoslavia. [6] November, 1919 during the Civil War in Russia. For three months of the winter, the girls, aged from 8 years upwards, were snowed up in a siding at Novorossisk in the Caucasus, until forced to flee by ship to Varna. Peasants gave them presents of food and fuel which kept them alive.

The ten girls are delighted to be in London. “We owe it all to our never-to-be-sufficiently-thanked Madame Maria Nekludova. Hundreds of us Russian girls owe everything, our education and upbringing, to her” they say.

English-language services were held at the Chapel of the Ascension in June and July, 1939. At the beginning of August, the Church Times published the following announcement, almost certainly authored by Canon John Douglas:

Russian Choir of Female Voices

Learning the Language

A Russian choir of female voices only is something of a novelty. A number of Russian young women have been brought over from Yugoslavia and given hospitality in various convents in and near London, and here they will learn our language and become acquainted with our Church life. England’s part in the work is conducted by the Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes, under the auspices of the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association. The other part, in Belgrade, is organized by a committee which has the patronage of the Queen of Yugoslavia.

This choir sings regularly at the Chapel of the Ascension, Bayswater Road, which the rector of St. George’s, Hanover Square kindly lends to Fr. Gibbes for the celebration of the Orthodox Liturgy in English. There are a number of members of the Russian Orthodox Church living in London who do not understand Church Slavonic. The choir will also sing both sacred and secular music at functions organized by the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association.

It is likely that there are other parishes, some perhaps not in a financial position to invite one of the larger Russian choirs, who be glad to have a visit from this choir of female voices. If so, they should write to the Rev. R. M. French, Secretary of the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association, St. James’s Vicarage, West Hampstead, N. W. 6. [7] Church Times, London. 1st August, 1939. P. 123.

Then, in August, 1939, the Chapel was closed (by the Anglicans) for annual holidays and some of the choir members left London for a holiday in the countryside or at the seaside.

The outbreak of World War II

However, the whole English Orthodox project never resumed in London, coming to a shuddering halt with the outbreak of World War II in September, 1939. Called “Operation Pied Piper”, the British evacuation of London began in preparation for the expected German Luftwaffe bombing of Britain. Fr Nicholas arranged for the ten women from Belgrade, who had been living in Anglican convents in the London area, to be re-housed in Anglican convents located in the countryside. Not surprisingly, the ten women, now refugees, were deeply unhappy about their situation. They were far from home, cut off from easy communication with Madame Nekludova and from their relatives in Serbia. Moreover, they were staying in Anglican convents where, necessarily, life was even more austere than in society at large. For the most part they were penniless, dependent on the goodwill of Anglican nuns. All were desperate to return to Belgrade and besieged Fr Nicholas with letters, begging him to help facilitate their return to Yugoslavia.

Fr Nicholas felt that their demands to return home were unreasonable; he thought that they were much safer in the UK. The journey to Yugoslavia in time of war would be perilous and, even if they succeeded in reaching Belgrade safely, their fate there was unknown and potentially full of danger. Nevertheless, he did attempt to secure the interest of the Yugoslav Legation [8]“A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. An embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a minister. Ambassadors outranked ministers and … Continue reading in Queen’s Gate, London SW7, as well as the League of Nations in helping his Belgrade Nightingales. He went to see the Yugoslav Minister in the first week of September, 1939. In a letter addressed to the ten women, Fr Nicholas reported that he had consulted the Yugoslav Minister who did not recommend them to return home at this present time. Fr Nicholas wrote to Maria Rodzianko, Choir Director,

All I wish to say is that he [the Jugoslav Minister] doesn’t see any necessity to return when they are provided for here. As it would be quite impossible to find the money for their Railway Tickets and I do not myself expect that they will be able to receive it from home – the question seems to be settled as far as they are concerned.

A month later, at the beginning of October, 1939, Fr Nicholas wrote again to the Yugoslav Minister “regarding the ten (10) girls from Jugoslavia, who are now in my care….” giving him details of their ages, passports, etc. and asking that Fr Nicholas be kept informed of any measures that might be taken for the protection of the young women. He received a reply, telling him that in fact one of the girls had been to see the Minister who informed Fr Nicholas that “the Legation is not, unfortunately, in a position to give financial help to her or to any other of the girls under your care who may wish to return home. All the Legation can do is to help them with their passports.” To another of the girls Fr Nicholas wrote,

The Legation have now plainly written to tell me that they will not give any money for the purchase of tickets, so unless your parents can persuade the Foreign Office in Belgrade to accept some money there and forward it to the Legation in London, I do not know how you can receive it.

A few days later, Fr Nicholas received the copy of a letter sent from Belgrade by Iakov Illiashevitch, the father of one of the girls, addressed in English to the “Right Honourable Sir High Commission for Refugees,” begging him to give financial assistance to the ten girls stranded in England.

In spring 1939, 10 girls of noble Russian families started from Yugoslavia to London in order to study the English language, to be able, later on, to earn their bread working in English offices here [in Belgrade].

These girls are refugees, come from Russia and have no pecuniary means whatever.

These young girls are boarded by the monasteries, but have no money for the necessary things, as clothing, postal-stamps, note paper, school books and fare for going to church, where they sing, etc. etc. Now because of the actual political situation, it is impossible for their relations to provide them with this money, as: 1/ money is not allowed to be sent out of Jugoslavia, and 2/ many of the relatives are now without work, owing to slack business in Jugoslavia.

Thus, these young girls are truly unfortunate. They are meanwhile, all of them, members-collaborators of the Fraternity, [9]Iakov V. Illiashevitch (1870 – 1953) was President of the Fraternity in Memory of Father John of Kronstadt which had been sanctioned by the Patriarch of Serbia in 1931 and also by the Yugoslav … Continue reading having helped it in different manners, singing at church-memorials or lectures and so on.

The Fraternity therefore considers it as the most sacred of duties to help these poor girls, by addressing itself to the High Commissioner, who took upon Himself the pecuniary aid to Russian refugees, and to beg Him to appoint a certain monthly sum to each of these girls for the above mentioned necessary expenses.

As the above mentioned young girls were admitted into the above named monasteries on the demand of the former tutor of the Russian Heir Apparent, Son of the late Emperor Nicolas II, now Abbot, Right Reverend Archimandrite Nicolas Gibbes, who knows where for the moment each of the girls can be found, the Fraternity begs the High Commissariat, in case the allowance would be granted, to kindly despatch it to the Right Reverend Archimandrite Nicolas Gibbes, begging him to hand it to the refugee girls according to indication.

Again, in October, 1939, Fr Nicholas wrote to the deputy of the Yugoslav Minister, Mr D P Subotić, telling him that two of the girls “are exceedingly bent” on returning to Yugoslavia. Fr Nicholas enquired as to whether it would be possible for their friends to pay in the money for their journey to some Ministry in Belgrade and for the girls to receive their railway tickets from the Legation here, the Legation being indemnified by the sum deposited in Belgrade. In parallel, Maria Alexeyevna Nekludova in Belgrade was making similar enquiries of government departments in Belgrade. Some success was achieved. By the end of October, Mdme Nekludova succeeded in sending a Banker’s Order for one of the girls, Irina Shahovskaya, in the sum of more than £4. [10] About £250 in today’s values. Her parents had provided the money through a businessman who already had some money deposited in London. As Fr Nicholas pointed out, £4 was not even half the fare from Belgrade to London. [11] This was not entirely correct. Fr Nicholas presumably was referring to the published price. However, as today, it was possible to find cheaper fares.

A historian of train travel, Mark Smith, suggests that perhaps travelling by train from London to Belgrade early in 1940 was not quite so hazardous as Fr Nicholas thought it might be. He writes,

I see no problem with Paris or even Calais to Belgrade. The Germans occupy France [May, 1940], Italy is their ally, the USA isn’t in the war, so no B17s over Germany yet, nor does the RAF have any heavy bombers. So, in 1940, everything should be operating fine on the most likely route, Paris-Lausanne-Milan-Zagreb-Belgrade. [12] Email to Nicolas Mabin, 1.5.2020.

With regard to the cost of travel, archivist Peter Thorpe of the National Railway Museum in York makes the following observation:

…for travellers that were very short of money, the advertised through prices between major European capitals may not be relevant. Even in the UK, it was possible to access cheaper than standard fares (group discounts, excursion trains, workmen’s fares, etc.) and it may well be the case that by making use of cheaper fares over shorter routes that they may have managed to make the journey at reduced cost. [13] Email to Nicolas Mabin, 11.5.2020.

The efforts of Fr Nicholas to facilitate the return to Belgrade of most of the girls to Belgrade seem to have petered out by the end of the year. It has to be noted that there seems to have been no suggestion that the A&ECA, as sponsors of the girls, nor indeed Fr Nicholas himself, should pay for the train tickets for the journey back to Yugoslavia. Yet the girls persisted and, as we shall see, some of them, together with their Choir Director, Maria Rodzianko, her husband and baby, succeeded in reaching Belgrade by March, 1940.

The Belgrade Nightingales

So, who exactly were the Belgrade Nightingales? Here is a brief portrait of each of the ten women (at the time referred to almost universally as “girls”). For some I have been able to write about their life after 1940; for others, regretfully, their story stops at 1940. I shall be happy to amend this paper as further information comes to light and I apologise wholeheartedly for any errors which may have crept in.

Julia Burachek

Julia Burachek, born on 5th July, 1916 in Helsinki, Finland, was 23 years old when she arrived in England with the Belgrade Nightingales in April, 1939.[14]Regarding the spelling of this surname, we follow the conventional Russian spelling – Burachek, although this name has been spelled as Buratchok and Buratchek in the British and American legal … Continue reading Julia travelled on a Yugoslav passport which had been issued in Pančevo. Notes from Fr Nicholas suggest that Julia was a student but not a singer. Together with Helen Rodzianko, Julia went to live at St Saviour’s Priory in Great Cambridge Street, Haggerston, London E2. At the onset of World War II Julia, together with Hele Rodzianko, relocated out of London, going to live at St. Mary’s Home, Littlemore, Oxford. [15] For more information on St Saviour’s and Littlemore House see the section on Helen Rodzianko. Like most of the other women, Julia wrote to Fr Nicholas, asking for his help in returning home, despite the War. She received little sympathy from Fr Nicholas who in October wrote to Julia:

I was very glad that you received a sensible letter from your parents. I entirely agree with all that they say and moreover the Royal Jugoslavian Legation says exactly the same thing. What is the use of asking further? You are closing your eyes to the fact that a terrible war is going on in France and that you will have to cross that country and in addition to that an enemy country as well. It is madness to take such risks without very good reason. You will have endless trouble getting visas and I do not think that you will be able to get money to purchase a ticket. The Legation have now plainly written to tell me that they will not give any money for the purchase of tickets, so unless your parents can persuade the Foreign Office in Belgrade to accept some money there and forward it to the Legation in London, I do not know how you can receive it. Why not take your parents’ advice? You are exceptionally well placed, near to Oxford, and not unhappy in your quarters. I therefore cannot understand why you are pitting your own will against an incontestable fate. Why not rather resign yourself to what God has sent? If you do that you will find much benefit will come of it. It is sent to you for a purpose.

However, Julia persisted and by December, 1939 it was clear that she would be making the risky journey back to Yugoslavia. Then in March, 1940, Fr Nicholas reports to Madame Nekludova in Belgrade: “Irina Shahovskaya and Julia Burachek are both planning to return home. Irina’s arrangements are all made but Julia is continuing her studies. (They will travel together when Julia’s expenses arrive.)” Julia indeed did leave for Belgrade and before the end of April, 1940, was once more resident at Madame Nekludova’s Kharkov Institute in Belgrade.

Through the chaos of the Second World War in Europe Julia, together with her parents and brother eventually reached the USA. In New York Julia received a university education and went on to have a very successful career with a New York investment bank. Julia was a parishioner of the Ascension Cathedral in Bronx, NY, the Annunciation Church in Flushing, NY, and then the Holy Protection Church in Glen Cove, NY. Julia passed away on March 26, 2005 and was buried next to her parents at the Novo-Diveevo Cemetery, Spring Valley, NY. [16]In an email (27th July, 2020) to the present writer, Archpriest Mark Burachek, rector of Our Lady of Kazan Church in Newark, NJ (ROCOR), expressed surprise that his aunt had ever spent a year in … Continue reading

Irina Demiankova

When Irina arrived in London, she was 27 years old and listed as a singer. Irina travelled on a Nansen passport [17]Nansen passports, officially stateless persons passports, were internationally recognized refugee travel documents, first issued by the League of Nations to stateless refugees. They became known as … Continue reading which had been issued in Belgrade. Accommodation for Irina had been arranged at the House of Charity which was located very centrally at 1, Greek Street. [18] Greek Street was closely associated with the Greek community which in the 18th century built an Orthodox church in nearby Charing Cross Road. The House of Charity was run by the Community of Saint John the Baptist with its Mother House in Clewer near Windsor, west of London. The main focus of the sisters in Soho was providing charitable support to the homeless. At the beginning of the Second World War the London House of Charity was requisitioned by the government and the Sisters moved back to Clewer. Before the work of the Sisters came to an end, they had expanded their charitable outreach to include

“people who were emigrating to Australia and were awaiting the long sea journey, people who had to come to London for surgery in hospitals, servants who had lost their jobs, teachers between positions and émigrés from Russia and the Balkans – an association which still continues to this day [2020] with the monthly services of the Macedonian Orthodox community in the Chapel [of St Barnabas].” [19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_St_Barnabas accessed May, 2020.

It seems, however, that Irina did not stay with the Sisters of Clewer in Soho Square for long. Soon we find her located at St Anne’s House, 34 Delamere Terrace, Maida Vale, London W2. This was a dependency of the Community of Saint Mary the Virgin at Wantage in Berkshire. [20] Peter Anson, The Call of the Cloister (London, 1955), 242-259. The Sisters lived at 34 and 35 Delamere Terrace, jointly named ‘St Anne’s’, and for daily prayer they used a chapel in the nearby Anglo-Catholic Church of St Mary Magdalene. The main work of the Sisters was performing charitable work within the parish.

The outbreak of war meant that Irina had to move again – this time far from central London. We do know that Irina went to live in Kent but there is no record of where in Kent. A possibility might be that the Sisters of the Church in nearby Randolph Gardens, Kilburn might have found room for Irina at the enormous 300-bed St Mary Convalescent Home and Orphanage at Stone Road, Broadstairs, Kent.

That Irina was living in a convent in September is clear from a letter written to her by Fr Nicholas. On 2nd October, after congratulating her on her recent Nameday (perhaps Virgin Martyr Irena commemorated on 1/14 September), Fr Nicholas tries to reassure Irina:

Of course, we are not cut off from Jugoslavia which is still a friendly country. I feel sure that the difficulty is that normally the mails would go through ITALY, which can (in spite of her neutrality) hardly be considered a friendly country!… There is the CENSOR to be reckoned with, that is sure to take a long time!

In your last letter you expressed anxiety about staying in your Convent. It is true that the original arrangement was for six months only, but I expect that the war will have altered that. WHEN the question is raised, I will find you a new place, but it is no use to meet troubles half way!… You will probably find that you are much better off here than if you were in Jugoslavia!…

At the end of October, in a letter to Irina Shahovskaya, Fr Nicholas comments, “The only one that I don’t have much news of is Irina Demiankova, who is in Kent.”

By mid-December, 1939, Fr Nicholas himself is planning to move to Oxford. In a letter to a correspondent in Belgrade, he writes, “Three of the girls are now in Oxford: Helena Rodzianko, Tatiana Jakovleva, and Julia Buratchok. The last does not sing but on her departure, it is proposed to put Irina Demiankova in her place. I shall then have three singers together again.”

It would appear that Irina did not return to Belgrade with the Rodziankos early in 1940. In March, writing to Elizabeth Alexandrovna Narishkin in Oxford about various arrangements needed in connection with the commencement of serving the Divine Liturgy in Oxford, Fr Nicholas states that he will write to “Miss Demiankova” and ask her to come to Oxford at the end of her quarantine. Presumably Irina had been sick and was now recovering. On 6th April, 1940, Fr Nicholas wrote, “Irene Demiankova will go to another Convent in Oxford, which is a sister house of the one she is now in. The Choir is not yet ready to start at Oxford. For one thing Irene Demiankova has not yet moved there and the soprano they have cannot sing alone.”

In 1942 Irina married Vatcheslav I. Ostroumoff. Born in 1899, Vatcheslav was at that time living in Charleville Road, Fulham, west London and working in road transport. Irina and Vatcheslav went on to have two children, Nathalie and Andrei. In May, 1947 the Ostroumoff family emigrated to Buenos Aires, Argentina. They travelled in third class on the Highland Chieftain, a Royal Mail Lines cruise ship, departing on the spring feast of Saint Nicholas of Myra, 9/22 May, 1947. The ship’s register, which notes that the whole family was “stateless”, records their last address in the UK: 14 St Dunstan’s Road, London W6. This, of course, was the podvorie, the London clergy house of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile.

Olga Illashevich

Olga Illashevich was the daughter of Iakov V. Illashevich (1870 – 1953) who was President of the Belgrade Fraternity in Memory of Father John of Kronstadt. She was born on 24th July, 1910 and so when Olga arrived in London, she was 28 years old. Olga travelled on a Nansen passport which had been issued in Belgrade. The choir member was accommodated in an Anglican Convent in Normand Road, Fulham, London W14, the Mother House of the Community of St Katharine of Egypt, an Anglican order of nuns founded in 1879. [21] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 455-457. Over the years the Sisters of Saint Katharine had undertaken various works of charity concerned with the welfare of young girls, especially orphans. By 1939, the main work at Normand Road was operating a hostel for girls on probation. The location for Olga was most convenient because the podvorie (clergy house) and All Saints Chapel of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile were located less than a mile away in St Dunstan’s Road, Baron’s Court, London W6.

As with the other women from Belgrade, at the outbreak of war, London was evacuated and Olga was sent off to a convent in the countryside. However, less than a week later Fr Nicholas wrote to the Choir Director, Maria Rodzianko, reporting that, “All the girls are still away except Olga Illashevich who returned a few days ago. Whether permanently or only temporarily I really cannot say.”

By the 27th October, 1939, Fr Nicholas was pondering the possibility of restarting the services at the Chapel of the Ascension, despite the threat of German bombing of London. Writing again to Maria Rodzianko, he says, “I am wondering whether it will be possible to fix up Tatiana Jakovleva somewhere in London. She very much wants to come. If she does that will make two (with Olga Illiashevitch). These with Ananina [22]The “Ananina” he refers to was Antonina Vladimirovna Ananina (d. 2006), godmother to the present writer. Antonina was not one of the Belgrade Nightingales but she was happy to sing in Fr … Continue reading and Panaevna would be four.” Soon after this, the possibility of serving in Oxford arose and all further thoughts of returning to the Chapel of the Ascension in London were abandoned.

In the same letter, Fr Nicholas writes more about Olga: “Illiashevitch didn’t like the country so well as London and, with the permission of the Mother Superior, has come back here. I had a long talk with the Rev. Mother and she said that she was glad to have her back in London.”

When the possibility of relocating to Oxford emerged in November, 1940, Fr Nicholas appears to have approached Olga about transferring to Oxford. Olga politely declined:

How difficult for me to refuse your kind offer and how thankful I am to you for all what you have done for me. Only my poverty obliges me to do what I don’t want. I am very sorry, that now I shall not be able to help you in a choir, what I wished sincerely… but London’s and Oxford’s future are unknown to us.

It would appear that Fr Nicholas was none too impressed with her decision and insisted that she leaves London. Olga wrote again to Fr Nicholas on 6th December, 1939:

I would like to ask you please not to be angry with me… The abbess asked me to write to you and to ask you, on my behalf and hers, to allow me to remain here [in London – NM] for Christmas. She asked me why you want to send me away from here? Her brother is serving in one of the “war offices” and told her that London is the safest place, as it is well protected from aerial attacks. She said that if it really gets dangerous, she will send me away immediately to Tankerton [Kent], where our nuns are currently living. The abbess herself told me that she would be sorry to send me there without there being an express need, since the only people there are old ladies and the infirm, whereas all the “visitors” have already fled from there. There is no-one to talk to there, since they are all elderly and are sitting around with their groups of friends, such that you see them only at table. I am simply in despair, as there are no opportunities whatsoever to practice the language there. In my view, Tankerton is not one bit safer than London, and therefore I would like to ask you not to send me away now. My father has nothing against my being in London. I wrote to him saying that if it gets dangerous, the abbess will send me away from here.

I am being helped in my lessons by a woman who lives here. She even wanted to pay for courses for me, should these get going. I have been promised work up until Christmas time, sewing dresses, and I hope to be able to earn something. In addition to this, Foka Feodorovich [Volkovsky; Choir Director at the Russian Church] is paying me a bit for my singing. All of these things combined compel me to ask you categorically to allow me to stay here.

In a draft of a letter to be sent in December, 1939 to somebody called Tatiana in Belgrade, Fr Nicholas wrote about Olga:

With the others [Olga] was evacuated from London into the provinces but – without consulting anyone – she returned to London. In answer to my enquiry she said that she had not been so happy in the country as she had been in London. I offered to find her another Convent, but this she refused. I have warned her of the possibility of danger by remaining in London – even if, up to the present, London has been safe. The responsible Ministers of the Crown have so frequently uttered warnings (see enclosed extract from the Prime Minister’s speech) that I cannot take the responsibility of keeping any of the Choir in London. I wish therefore, in advance, to disclaim all responsibility for anything that may happen to Olga Illashevich. I shall be very glad if you will be so kind as to inform her father to this effect.

It is not clear whether this letter was actually sent. However, Fr Nicholas did write again on the subject, this time to Madame Nekludova in Belgrade on 12th March, 1940. He reiterated that Olga had refused to be located outside London and that he disclaimed all responsibility for Olga if anything happened to her as a result of being in the London Blitz, together with a request to tell her father the same.

Indeed, in 1940 Fr Nicholas “washed his hands” of any responsibility for Olga. He wrote to Madame Nekludova again in April, 1940 and his irritation, bordering on anger, comes through clearly:

I must also tell you that Olga Illiashevitch has chosen the Rev. Father Michael Polsky as her Father Confessor. I therefore consider that she has ipso facto become a parishioner of a parish other than my own. I offer no objection to her doing as she prefers, but I cannot receive into my choir or take under my protection the ‘spiritual children’ of any other priest or parish. I therefore propose to hand over the care and charge of Olga Illashevich to the Reverend Father Michael Polsky. I have not yet spoken to Olga on this subject. I would prefer you to write to her and tell her of this transfer. Please inform Olga at once and let me know as soon as you have done so. She will then be excluded from my organization. It would perhaps be as well to make this question clear to them all. They are all quite free to do as they like but whoever is their spiritual father will have to undertake the responsibility and work of looking after them.

1968 At the Cenotaph, Whitehall: Panikhida for the slain Russian Royal family: (l.-r.) Tamara Labarnova, (partially) Olga Mackellar, (partially) Valerie Holmes, Olga Illyashevich, Countess Bobrinskoy, Matushka Antonina Jeffimenko, and Antonina Ananin.

Olga remained in London throughout the war and in March, 1940 was granted permission to remain in the UK indefinitely, becoming a British citizen in 1951. The present writer first met Olga Illashevich in the early 1970’s when she was living in Notting Hill Gate, west London. Olga had already retired from her work as a shorthand typist in an insurance company in the City. Olga remained a faithful member of the Choir and of the Sisterhood of Saint Xenia at the London Russian Orthodox Church in Exile until her repose in 1987 at the age of 76. She is buried in Gunnersbury Cemetery, London W3.

Tatiana Jakovleva

Tatiana was born in Russia in 1914. Travelling to England on a Nansen Passport in 1939, Tatiana was 22 years old when she arrived in London. There, together with Sofia Kvachadze, she was accommodated at the Anglican Community of St Peter in Kilburn, north London. [23] For more information on this Anglican community, see the section on Sofia Kvachadze. Tatiana was a member of the Choir. In September, 1939 both Sofia and Tatiana were evacuated from London and re-settled at the Community of Saint Peter, Maybury Hill, near Woking in Surrey. In October, Fr Nicholas toyed with the idea of bringing Tatiana back to London in order to re-start the Chapel of the Ascension project. However, by December Tatiana managed to secure for herself accommodation in Oxford, not in a convent but in a private home which meant that she could live in Oxford and progress her studies. In March, 1940 the Home Office informed the Church of England Council on Foreign Relations that Tatiana need not apply for further permission to remain in the UK while she was unable to return to Yugoslavia. By August, 1940, she had moved to Kilburn (north west London) where she had obtained a job which would allow her to attend the courses she had wanted.

In 1943 Tatiana married George Knupffer. George and Tatiana had three children, Michael, Marina and Alexei. Living in Chiswick, west London, the Knupffer family were devoted members of the London parish of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile. For many years George served on the Parish Council. George was well known for his right-wing views, publishing many pamphlets about world politics and, in 1963, a book entitled The Struggle for World Power (London, Plain-Speaker Publishing Co.). George died in 1990, aged 82. Tatiana passed away twelve years later in 2002 at the age of 87. She was survived by three children and four grandchildren. Both George and Tatiana were laid to rest at Chiswick New Cemetery, London W4.

Sofia Kvachadze

Sofia V. Kvachadze (always known as ‘Sonia’) was born on 10th November, 1908. When she arrived in England in 1939, Sonia was already 30, making her the oldest of the Belgrade Nightingales. Like most of the other group members, Sonia was stateless and travelled on a Nansen passport. She was not a singer and did not claim to be, nor was she a student. The archives suggest that she had some competence in painting of icons but, from Sonia’s point-of-view, perhaps this capability was overstated. It is unclear where she was living in London initially. It was probably at the Mother House of the Community of Saint Peter, Mortimer Place, Kilburn, north west London. This Community of Anglican nuns (most of whom were ordained deaconesses) had been founded in 1861. War damage to the Kilburn location subsequently forced the Community to seek new headquarters in Woking, Surrey. [24] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 385-393. However, not long after arriving at St. Peter’s, Sonia appears to have taken up new accommodation at St. Mary’s, Burlington Lane, Chiswick, west London, a convent of The Society of St. Margaret, another Anglican order. [25] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 336-355. The St. Mary’s Convent and Nursing Home is still located in Chiswick, just over a mile away from the new London Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia in Harvard Road, London W4.

At the end of August, Sonia is mentioned in a letter to Fr Nicholas, sent by the Choir Director, Maria Rodzianko. At that point Maria and her husband were arranging to move back to London from Cornwall. If that were to happen, then Maria would be able to do more with the choir but she needed a babysitter. “I thought about Sonia Kvachadze, but she is so busy in her Convent that I am really afraid that it will be hardly possible. I do not think they will allow her to be absent for long periods as would be the case, for instance, with our concert in Hove [in East Sussex, about 50 miles from London].” With the onset of World War II, the Rodziankos did not move back to London and, of course, the Hove concert was cancelled.

As part of the evacuation of London, Sonia then moved to Woking (about 30 miles from London) and lived at the Community of Saint Peter, Maybury Hill. [26] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 385-393. Together with Tatiana Jakovleva who was also living at St Peter’s, Sonia wrote a number of times to Fr Nicholas, expressing their unhappiness in their current situation. They felt that they should be paid for their work in the Convent: “we fear to be left in the convent without a penny… We are both able to work, hence it is much more pleasant for us to do paid work than use charity.” Like all the other women from Belgrade, Sonia was concerned about obtaining funds in order to return to Belgrade. Fr Nicholas was not encouraging in this regard.

In March, 1940 she wrote yet again to Fr Nr Nicholas, expressing again her unhappiness, especially with the departure of her close friend, Tatiana Jakovleva, who had left the Convent in December and had found accommodation in Oxford where Tatiana could continue with her studies:

Please forgive me for writing to you again and troubling you with a question. I have again ended up in an inconvenient situation in the monastery. Since Tania left, they are constantly putting guests who come to the monastery for some time, in my room to sleep. Sometimes for one night, sometimes for two or more. This is extremely unpleasant, all the more so given that these people are complete strangers to me. The main issue is that I can never be sure when I will be alone and how often these guests will be coming.

The last mention of Sonia in the papers of Fr Nicholas was in March, 1940 when the Home Office wrote to say that Sofia Kvachadze was able to remain in the UK indefinitely.

1977: At the Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile, Emperor’s Gate, London SW7, Archbishop Anthony (Bartochevitch) holds the cross; to the left is Sofia Kvachadze.

In fact, Sonia remained in London for the rest of her life until her repose in 1990. The present writer made her acquaintance in the early 1970s by which time Sonia had retired and was living in one of the retirement homes run by the Russian Red Cross [27]https://www.northumbria.ac.uk/media/7245181/daniel-harold-russian-exiles-in-britain.pdf (accessed July, 2020). The Russian Red Cross was one of the most successful organizations in terms of … Continue reading in Bedford Park, Chiswick, London W4. Sonia remained a stalwart of the London parish of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile and was an active member of the Sisterhood of Saint Xenia. After her repose at the age of 81 on 17th September, 1990, the earthly remains of Sofia Kvachadze were interred in Chiswick Cemetery, London W4.

Marina Liamina

Marina Liamina was born on 16th July, 1916. Being a stateless refugee, the 24 years-old Marina travelled to London from Belgrade in April, 1939 on her Nansen Passport which had been issued in Belgrade. Marina was not a member of the choir; she was designated as a student. Together with Nina Semenova, Marina was accommodated at first by the Anglican Sisters of the Church in Randolph Gardens, Kilburn, London NW6 where the nuns managed a large orphanage. [28] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 439-446. At the outbreak of World War II Marina, together with Nina Semenova, went to stay at the School of St. Michael in West Grinstead. [29]Founder of the community at East Grinstead, Fr John Mason Neale (1818 – 1866) was a Church of England clergyman who was a great scholar and a keen observer of the Eastern Orthodox Church. He was … Continue reading

From West Grinstead Marina and Nina wrote numerous letters to Fr Nicholas, imploring his help in arranging for their return to their homes in Belgrade. As mentioned in the section on Nina Semenova, they even made a visit to the Royal Yugoslav Legation in London, asking for financial assistance. They felt very lonely at St. Michael’s. In October, Marina wrote to Fr Nicholas,

As for our life here, there is no change for the better, we are quite alone the whole day & owing to this there is no use in our staying here. As we know that all arrangements for visas may take very long time, we should like to take advantage of the rest of our staying here & make it as profitable as possible. We should be most grateful to you if you would do what you intended to improve our conditions here. The only person with whom we could speak a few words in the evenings, a Lady-Cook. is leaving this house now & our isolation will be complete. We are still not allowed to be in the company of 10 Mistresses who live in this house. We are desperate at the thought of quite useless wasting of time…

Fr Nicholas took it upon himself to try to get the situation of the girls improved. The incident encompasses a brief insight to the class prejudices of the time. He wrote a remarkably sensitive appeal to the Mother Superior at East Grinstead:

I have had a letter from one of my spiritual children who is now living with you and I don’t quite know what to do about it. It is rather breaking their confidence to show it to you, but, on the other hand, it expresses the “feelings” of both of them so well that I think it would be best for you to see it. I am therefore enclosing it (in confidence) for your information.

Obviously, the girls are very sensitive and in a great establishment such as yours, they feel rather “lost.” It is the usual feeling of all little boys and girls going to a great public school for the first time. For although these girls are actually grown up, circumstances have placed them in an analogous position. They do not understand and it is impossible to explain to them what a “teaching staff” means in England. How individually they are all kindness and simplicity, collectively they are very conservative and reserved and would not like, most probably would resent, ‘having strangers around.’

The chief difficulty seems to arise from the fact that they are now doing work which classes them with the servants, whereas in birth and education they really belong to the higher staff. All the girls that are with me are from noble families and these, as most of the others, have already matriculated at the University.

May I leave it with you to decide whether any adjustments are possible? If it is not, you can advise me accordingly and I will try to make some other arrangement for them and this correspondence need never come to light. I am very much afraid to impose on your kindness in any way. It was most awfully good of you to take them in at a moment’s notice and I was more than grateful for your quick response to our trouble at that time of great difficulty. The girls are warm in their praise of all the physical care that has been taken of them since they have been under your roof, and are suffering only from this terrible sense of loneliness. At first, I took little notice of their plaint, hoping that time itself would adjust matters but, since it has not, I am venturing to write you this letter. Asking your holy prayers, I remain very sincerely in Our Lord…

We do not have a copy of the reply from Mother Superior but on 4th November, Fr Nicholas wrote to her again:

I am indeed most grateful for the very kind way in which you have received my request. I was convinced that it was all an oversight and therefore ventured to bring it to your notice. I am very glad that I did so for I am sure that the girls will now be quite happy.

Despite the improvement in living conditions at St Michael’s School, the two girls persisted in their quest for a return to Belgrade. In December Marina wrote to G. J. Kuhlmann, Deputy High Commissioner of The League of Nations in London. As a result, on 19th December, 1939, Mr Kuhlmann wrote to Fr Nicholas. Fr Nicholas replied by return:

With regard to Miss Liamina’s letter, a copy of which is enclosed in yours of the 15th, I can only say that I was quite unaware of her intention to apply to you direct. It is however a fact that the girls who came here from Yugoslavia did not all intend to remain the same length of time. These periods varied between six months and two years. Only one elected to stay so short a time as six months: that was Miss Liamina. I state this to show that her decision to return home is not due to any kind of panic or caprice but in accordance with her predetermined plan.

I remember very well your saying that there were no League funds available to assist the girls individually, and I have conveyed this information to them. I must also state that I do not think that she is being pressed to leave the Convent where she is now staying or that it would be impossible to find her another. She and Miss Semenoff are not particularly happy where they are although I succeeded in improving the conditions in which they are living and they are now not in any way “unbearable”.

At the same time, I know that in her particular case circumstances do call for her return home and it is for this reason that she is making such determined efforts to accomplish her end. Personally, I shall be very sorry when she goes because she is a singer, [30] This may have been stretching the truth since notes made by Fr Nicholas in August, 1939, indicate that Marina was not a singer. but I do not feel that I can allow this to stand in her way. I am wondering whether you might be able to influence assistance to her from sources other than the League? I fully realize how difficult that is thought naturally, especially at the present time.

Despite all the difficulties — war, a dangerous crossing of the English Channel, and the lack of funds — Marina reached Belgrade early in 1940. In a letter of 25th April, 1940, Madame Nekludova reported to Fr Nicholas, “Marina Liamina comes to the [Kharkov Institute] hall of residence on the days when she comes to Belgrade for lectures… Marina already has English lessons; she has to help her aunt, with whom she lives and who is quite like a mother figure to her.”

Helen Rodzianko

Helen Rodzianko was 18 years of age when she arrived in England in April, 1939. Like most of the other women from Belgrade, she held a Nansen passport. As the South Slav Herald of June, 1939 had noted, Helen was the granddaughter of the last President of the Russian Duma, Mikhail Rodzianko (1859-1924). She was the sixth of eight children and the first to be born outside Russia after the family fled to Serbia in 1920.

In London, Helen was accommodated at St Saviour’s Priory which was located in Great Cambridge Street, Haggerston, London E2. This was a daughter house of the Society of Saint Margaret. [31] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 336-355. See footnote 25 above. The East London branch house had been established in 1868. In addition to their life of prayer, the sisters served the very poor local communities with an array of charitable works. Initially, it must have been a shock for Helen to live in such a deprived area.

Previously known as Lawn Upton House, in the 19th century the land on which it stood had belonged to John Henry Newman (d. 1890), later Saint John Newman of the Roman Catholic Church, who at that time was Anglican priest of Littlemore. In 1836 he caused to be built the nearby church of Saint Mary and Saint Nicholas which became a centre of Anglo-Catholicism. St. Mary’s Home was one of numerous foundations of the Community of St. John the Baptist, Clewer, Windsor, Berkshire. The Community took over Lawn Upton House from 1929 to 1953 and established there a home for ‘wayward girls.’

Late in September, 1939, Fr Nicholas was asking Helen to return to him the keys to Saint Philip’s Church and choir music books. In fact, Helen had accidentally left them behind at St Saviour’s in east London. Eventually the items were returned to Fr Nicholas by Helen in a parcel sent from Littlemore. Thanking Helen, Fr Nicholas wrote:

I am so glad that you have settled down in Oxford. You are very lucky to be in such an advantageous place. I hope that you will make good progress in your lessons. If you want any help or advice in your studies you will be able to consult Mr. Subotić, the Inspector of Education, of the Jugoslav Legation, who is in Oxford…

The arrival of Helen and another choir member, Tatiana Jakovleva, in Oxford had prompted the local Russian community to invite Fr Nicholas to relocate from London and go to live in Oxford in order serve the Divine Liturgy there, supported by at least some of his Belgrade Nightingales. Late in December, 1939 he reported to a correspondent in Belgrade:

Three of the girls are now in Oxford: Helena Rodzianko, Tatiana Jakovleva, and Julia Buratchok. The last does not sing but on her departure, it is proposed to put Irina Demiankoff in her place. I shall then have three singers together again. This has inspired some of the Russians living in Oxford to try and organize Orthodox services in that City. Arrangements are now complete. When they are quite concluded, the Church organisation which we had in London will be moved to Oxford.

There is a glimpse of Helen in a rather critical letter written by Elizabeth Alexandrovna Narishkin (d. 1945) who was helping Fr Nicholas to set up the Orthodox community in Oxford. Elizabeth was rather concerned by the lack of sheet music for the choir. “It is extraordinary how extremely unmusical both Helen and Tania are, and although they know the tune, they cannot stick to it without music.”

Helen’s daughter, Zina, recalls,

Every Saturday evening, Father Nicholas would show up at her college gates, his beard spreading over the chest of his cassock, and a long staff in his hand. The Belgrade Nightingales had scattered and he needed to know if she would be in church tomorrow, as by now she was all that remained of his choir. [32] http://zinarohan.squarespace.com/family-article/ accessed June, 2020.

In Oxford Helen studied English and then went on to graduate with a first-class degree in Russian at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Helen had become President of the Russian Society in Oxford and it was in that capacity that she met her future husband, at that time also a student of Russian at Oxford. This was George Rapp (d. 1982), a Jewish refugee who had escaped from Germany in 1935, only to be interned as an enemy alien by the British in Australia, nine months into the Second World War. By 1944 George had been released, returned to England, and married Helen in a civil ceremony at Willesden Town Hall, north west London.

In the 1950’s Helen completed a doctorate at the London School of Slavonic and East European Studies and returned to Oxford to teach Russian. In 1962, together with Frank Seeley (d. 2000), Helen published a best-selling Russian language studies textbook. In 1960 Helen joined the BBC as a producer of arts programmes for Radios 3 and 4. Helen left the BBC in 1969 and became responsible for the arts curriculum radio broadcasts of the newly established Open University. It was at this time that Helen separated from her husband.

Helen died in 1998 at the age of 78. Her funeral was held at the Russian Cathedral at Ennismore Gardens (Moscow Patriarchate). She was buried at the Islington and St Pancras Cemetery in East Finchley, north London. Helen was survived by two daughters, Miriam Newman (d. 2000), the author Zina Rohan, and five grandchildren.

Nina Semenova

Born on 29th July, 1916, Nina was 22 years old when she arrived in England in April, 1939. Nina Semenova was a student but did not sing in the choir. Nina held a Yugoslav passport which had been issued in Belgrade. Her accommodation on arrival was provided by the Sisters of the Church in Randolph Gardens, Kilburn. This was the Mother House of the Sisters of the Church, an enormously successful Anglican order which operated dozens of orphanages and schools both in the UK and overseas. In 1939 the Randolph Road site was both a convent and a large orphanage. A year later it was destroyed by Nazi bombing and the Sisterhood relocated the Mother House to Ham Common in Surrey. [33] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 439-446. As we saw with Sofia Kvachadze, the Choir Director, Maria Rodzianko, was casting around for a prospective babysitter. Nina Semenova was her preferred choice. Writing to Fr Nicholas at the end of August, Maria said,

Nina Semenova, I think, is the only person who, if she is in London, will be in a position to do it, as she is, more or less, free in her place. I had written to her to ask whether she would do it for me, if you find it possible to retain her in London. She replied to me at once that she is very glad to undertake that responsibility.

However, with the outbreak of war and the evacuation of London, Nina, together with another member of the group, Marina Liamina, had to relocate to St Michael’s School in West Grinstead, Sussex, [34] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 336-355. See footnote 25 above. some 50 miles from London. Nina and Marina were fervent in their desire to return to Yugoslavia and sent many letters to Fr Nicholas, imploring his help. In October, 1939 they even went to see Mr Subotić at the Yugoslav Delegation in London, seeking his help in facilitating their return.

In November, 1939, through the intervention of Madame Nekludova in Belgrade, Fr Nicholas was able to send Nina a remittance to the value of about £120 in today’s values which he had received via the London bank account of a Russian businessman based in Belgrade. A letter in November from Helen Rodzianko to Fr Nicholas mentioned Nina: “We are still very happy in here [in Oxford]; we try to study as much as possible and hope to see soon Nina Semenova and Maria Liamina. We wonder whether it is possible to put them somewhere in Oxford?” A month later, Fr Nicholas responded to a letter from the G. J. Kuhlmann, Deputy High Commissioner at the League of Nations. The letter is mostly concerned with Maria Liamina. However, Fr Nicholas says about Nina, “[Marina Liamina] and Miss Semenova are not particularly happy where they are although I succeeded in improving the conditions in which they are living and they are now not in any way “unbearable”.

Writing about Nina and also about Marina Liamina in December, Fr Nicholas expresses his frustration with girls: “They are working in one of the very best schools in England and I consider them very fortunate to have this experience though I am sure they do not yet quite realize its value.” He goes on to say, “They were here [at the podvorie in west London] on Tuesday to arrange their papers for travel and they informed me that, since the day previous, efforts had been made to render their position [at the school] happier and they spoke, for the first time, with regret at the possibility of their having to leave England soon.” [35] See the section on Marina Liamina as to exactly what caused their unhappiness at St Michael’s School.

In any event, Nina and Marina were successful in obtaining the necessary papers for return and early in 1940, despite the fact that Europe was at war, and regardless of the great risk of crossing the English Channel, they succeeded in returning to their home in Belgrade. We learn from a letter (25th April, 1940) sent by Madame Nekludova to Fr Nicholas that Nina was once more living at the Kharkov Institute in Belgrade.

Irina Shahovskaya

Our first introduction to Irina Shahovskaya was in the English-language South Slav Herald of June, 1939 (see above), which reported that Irina was a princess and that she would be singing soprano at the Russian Church in London. In 1939 Irina was 22 years old. As with most of the women from Belgrade, Irina held a Nansen passport. On arrival in London Irina became a guest of the Society of the Sisters of Bethany at Lloyd Square, Clerkenwell, London WC1, an Anglican religious order founded in 1866. [36] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 405-412. The main activity at Lloyd Square was the holding of religious retreats for women, as well as conducting works of mercy and charity in the exceedingly poor neighbouring districts. The community had also become famed for its School of Embroidery and perhaps Irina would have helped with this activity. The Community of the Sisters of Bethany is still in existence but the Lloyd Square site was closed in 1962.

Doubtless, the Sisters of Bethany would have told Irina about a visit made to their convent back in November, 1937 by the Kursk-Root Icon, which was brought to them by Archbishop Seraphim (Lukyanov) of Paris, Fr Nicholas Gibbes and Fr Michael Polsky. There was a moleben (service of intercession) in the Convent chapel before the Icon was taken by the visiting Russian Orthodox to the nearby hospital of St Barnabas where the Convent Chaplain, Fr Bartlett, was a patient. Together with other patients and nurses, he was blessed with the Icon. [37]J. Salter. “The Sisters of Bethany and the Eastern Churches.” Eastern Churches Newsletter. 5. Autumn 1977. 23. Salter wrongly suggests that the visiting Archbishop was Metropolitan Evlogy … Continue reading

With the outbreak of World War II, Irina was sent to Bournemouth, Hampshire, a seaside resort, about 120 miles from London. There she lived at the House of Bethany which was partly a convent and partly a guest house where retreats were held. However, she was deeply unhappy there and wrote several times to Fr Nicholas, asking for his help with enabling her return to Belgrade.

At the end of October, 1939, Fr Nicholas wrote to her in no uncertain terms, instructing her not to wish for something which, in his view was, unachievable. Having consulted with the Office of the League of Nations, he assured her that in the present circumstances it was impossible to transfer money from Belgrade to England in order to fund rail travel. He said that the Deputy Commissioner at the League of Nations, as well as the Yugoslav Minister, were united in their advice against making the journey. In any event she was “fortunate to be in Bournemouth, which is always considered to be one of the finest of the English resorts.” Fr Nicholas then responded to yet another letter from Irina in which she said that her mother and her sister were demanding that she return to Belgrade. They had heard that the Rodziankos were planning to return to Belgrade and they instructed Irina that she should travel with them. Fr Nicholas agreed that, if such was their wish, then she had better obey. He also was able to give Irina some good news. Madame Nekludova had arranged for money to be sent to Fr Nicholas for onward transmission to Irina. It came from the London bank account of a Russian businessman, in today’s values about £250.

Irina did return safely to her family in Belgrade sometime after March, 1940. In an uncharacteristically critical note to Fr Nicholas (25th April, 1940) Madame Nekludova comments, “Only Irina Shahovskaya rushed to return home, not having learnt everything that is necessary to get a good place and I do not approve of that.”

Ludmilla Vedrinskaya

Ludmilla Sergievna Vedrinskaya was born in Voinovka, nowadays the Republic of Bashkortostan, Russia on 7th January, 1918. [38] This is her birth date in UK records. However, Ludmilla’s gravestone gives as her date of birth 24th January, 1919. In 1939 Ludmilla Vedrinskaya was 21 years old. She held a Yugoslavian passport. Notes from Fr Nicholas suggest that Ludmilla was a student but that she could not sing, and therefore did not form part of his choir.

On arriving in London, Ludmilla went to stay at St Andrew’s House, Tavistock Crescent, Westbourne Park, London W11. [39] Anson, Cloister, 1955, 457-462. However, in June, 1939 Ludmilla fell ill, having to undergo an operation in hospital. She then went to Bournemouth for recuperation at the Herbert Convalescent Home in Bournemouth. On 29th June Ludmilla left the convalescent home and went to live with the Community of the Epiphany in Truro.

Some 250 miles from London, the Convent in Truro, Cornwall, was home to the Community of the Epiphany, an order of Anglican nuns. The sisters were involved in pastoral and educational work, the care of Truro Cathedral and nearby St Paul’s Church, as well as church needlework. It is likely that Ludmila would have earned her keep by contributing to the department for church embroidery.

In September, 1939, the Anglican Chaplain of the Convent suggested to Ludmilla that she should partake of the Anglican Holy Communion, given that she was cut off from her own Church. Fr Nicholas responded that he could not give his blessing for this, albeit very reluctantly. He explains that “although it is true that cases of inter-communion have been allowed, it is still (unhappily) not permitted in our branch [sic] of the Holy Orthodox Church.” Fr Nicholas does not question the efficacy of the Anglican Holy Communion. Instead, he writes, “So that even to obtain for you such an inestimable advantage, I cannot do as he [the Anglican Chaplain – NM] suggests, much as I should like to…”

By happy chance the Choir Director, Maria Rodzianko, was living at Bodmin, about 30 miles from Truro. In October, 1939, Maria wrote to Fr Nicholas:

…Yesterday Ludmilla Vedrinskaya was here to see me and we had a very nice afternoon. She is evidently very happy in the Epiphany Home [and] has made on me a good impression. She has changed for the better very much indeed. I hope to visit her there sometimes. I like so much the Convent’s atmosphere. She has told me about your letter and about the Communion problem. We are looking forward for your or Father Michael’s visit. There will be a church and an English choir can sing the whole of our liturgy in English.

In a return letter, Fr Nicholas said that he had had a nice letter from “Vedrinskaya”.

…What a good thing we sent her to Truro, even against her will. She seems now to like it very much and she herself is certainly improved. Possibly the good food and good air have strengthened her morale as well as her body. Very often they go together.

Ludmilla received permission to stay in the UK permanently in March, 1940. Thereafter, the next we learn of Ludmilla is that on 5th July, 1944, in High Wycombe, Berkshire, Ludmilla married an American soldier, Boris Maximoff. Seven months later, in February, 1945, Ludmilla set sail for the USA aboard the US military ship, the Thomas H. Barry. The ship’s passenger records notes that at that time Ludmilla was 27, a housewife, who was able to read and write not only English and Russian but also Serbo-Croat and French. [40] Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006. Ludmilla arrived in Boston in March, 1945 and went to live in Chicago and subsequently in Dayton, Ohio,

Memorial Cross at the grave of Ludmilla Maximoff (née Vedrinskaya), Novo-Diveevo Cemetery, New York.

where a city directory of 1946 has her listed under her maiden name as a professional translator. [41] Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011. In September, 1977, Ludmilla passed away in Spring Valley, Rockland, NY and was buried in Novo-Diveevo Russian Orthodox Cemetery. She was survived by her husband, Boris (d. 2009) and three children, Sergius, Nicholas and Catherine.

Maria Rodzianko

Maria Vasilievna Rodzianko was not one of the Belgrade Nightingales. She had arrived in England in 1938 with her husband, Vladimir. However, Maria was appointed by Fr Nicholas to be the Choir Director of the Belgrade Nightingales and it would be remiss not to record her part in the project.

Maria (née Kulyubaeva), the daughter of a priest, married Vladimir Rodzianko in 1938 in Belgrade. Vladimir had graduated from the theology department of the University of Belgrade in 1937. He and Maria then moved to England where Vladimir began working on a dissertation for the University of London. At the same time, Vladimir travelled widely in England, speaking to various groups about the Orthodox Church under the auspices of the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius. After their arrival in London in 1938, Maria and Vladimir had their first child, also called Vladimir.

An anonymous document in the archives of Fr Nicholas records that “The Choir Mistress [of the Belgrade Nightingales] is the talented Madame Maria Vasilievna Rodzianko, who not only herself possesses a remarkably pure contralto voice, but also conducts the choir with great ability and feeling.”

At the beginning of 1939 Maria with her baby son went to live in Bodmin, Cornwall at the home of Fr A C Canner, Anglican priest of the parish of Tintagel. Meanwhile, her husband was based in London, living at the home of the great friends of Fr Nicholas, Prince and Princess Vladimir Galitzine, but travelling outside of London extensively. Then in July, 1939 he went to live with his wife and son in Cornwall.

The Rodziankos had been planning to return to London as a family: there was a suggestion that they would live in a guesthouse in Belsize Park (north London) but the outbreak of World War II put paid to that idea. In fact, the Rodziankos determined to return to Belgrade as urgently as possible. Evidently Maria had written to the choir members, telling them of these plans. This upset Fr Nicholas because he thought that there was little prospect of that dream becoming a reality. On 9th September, 1939, he wrote rather sharply to Maria:

As it would be quite impossible to find the money for their Railway Tickets and I do not myself expect that they will be able to receive it from home – the question seems to be settled as far as they are concerned. Therefore, do NOT make any suggestions to the contrary. Your letters to them on this subject have had a very disturbing effect. It is quite useless to suggest their going back to Jugoslavia unless you have the money for their Railway Tickets.

Nearly a month later Maria replied:

Thank you so much for your last letter. I was really sorry to hear that my letters had disturbed so much the girls. But I must say that some of them had written to me before I ever dreamed to advise them to be ready to go to Yugoslavia. They were very anxious what will happen with them and Liamina and Semenova expressed their earnest desire to return back to Yugoslavia. I have written to you but you were not able to answer me quickly and I thought it would be unkind not to discuss this question with the girls themselves, for I thought we will succeed in getting the visas and I could imagine what would the girl’s parents ask me in that case. So, I decided to write to them, asking them whether they want to go to Yugoslavia and whether they have any means of going there, and whether their parents are in a position to help them with this and so on. I never advised them to go, and only asked them, saying what they have to do in case they want to go. Of course, now it is evident no one [sic] of us is able to go and therefore everything must remain it was.

I am really sorry for all the trouble I made by my letters, but I did not think it will happen.

Unfortunately, Volodia has not got the B.B.C. job we don’t know why. It was of course disappointing, but I hope he will be able to work on [unclear] Farm, or doing gardening near Bodmin.

To which Fr Nicholas replied:

I have wondered many times how Volodia is getting on as a “farmer’s boy”. (There is a very celebrated song of that name: does he now sing it?) It was a pity he didn’t get the B.B.C. job, but they are not easy to get. I should think that his English was not good enough. He ought to improve his grammar – which (although he hardly believes it) is bad. Let him mark my words.

Early in 1940 the Rodziankos made it back safely to Belgrade, Yugoslavia. There Vladimir was ordained to the priesthood in March, 1941. In 1949 Fr Vladimir was sentenced to eight years’ hard labour for promoting ‘religious propaganda’. In 1951, Fr. Vladimir was released from prison and reunited with his wife, Maria, and their two sons, Vladimir and Michael. After his release they went to France before settling in England where Archpriest Vladimir became a priest of the Serbian Orthodox Church in London. He was offered a position broadcasting on BBC services and for more than 30 years, he produced religious programs that were broadcast to the Soviet Union. For many years Maria also worked at the BBC as a presenter of Russian religious programmes. Tragically, Maria Rodzianko died suddenly in 1978 at the age of 62. She was laid to rest in Chiswick New Cemetery, west London. Following the death of his wife, Fr Vladimir became a monk and in 1980 became Bishop Basil of Washington for the Orthodox Church in America, later becoming Bishop of San Francisco, and retiring in 1984. He passed away in 1999 at the age of 84. [42] See http://www.rodzianko.org/english/life/ accessed June, 2020.

Epilogue

Less than six months after the Belgrade Nightingales had arrived in England, the exigencies of war led to them being scattered. Some made the perilous journey back to Belgrade where in due course they were to experience the horrors of the Nazi regime and later the oppression of the Communists. Others stayed in England and lived through the Second World War and the German Blitz. Three went to Oxford and this inspired the small Russian colony there to start a parish, inviting Fr Nicholas to leave London and live in Oxford where he served the Divine Liturgy for the Oxford community, supported initially by three of his Nightingales. Serving at first in Bartlemas Chapel, some years later Fr Nicholas would go on to acquire his own church property, the predecessor of today’s parish of Saint Nicholas in Oxford. In March 1940, Fr Nicholas wrote to Metropolitan Seraphim in Paris and told him of these developments:

Little by little part of the choir has gravitated to Oxford. First two, then a third and now I am hoping that a fourth will also shortly come. This has made it seem possible to the small group of Russians living in Oxford to ask me to begin regular Orthodox Services in that city. The principal difficulty has been to obtain a suitable place of worship, but even that has been, by the Grace of God, now overcome. A small and very ancient Chapel, dedicated in honour of St. Bartholomew, has been placed at our disposal. …[T[he Chapel is now attached to one of the Oxford Parish Churches, whose vicar is allowing us its use. This kind action only awaits the official sanction of the Bishop of the Diocese and the Chapel can then be used by us. I have therefore the honour to report the above facts and humbly to beg Your Lordship’s episcopal blessing on all that has been done and further to request Your official sanction to hold Russian and/or English Orthodox services in the Bartlemas Chapel in the City of Oxford.

Bartlemas Chapel in Oxford where Fr Nicholas served Divine Liturgy from 1940 to 1945, initially with a choir of three Belgrade Nightingales.

At this time, Fr Nicholas was still within the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile but in 1943 he removed himself to the Moscow Patriarchate. [43]See: Nicolas Mabin, Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes: From the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile to the Moscow Patriarchate … Continue reading

As for the Chapel of the Ascension, sadly on 18th June, 1944, it was listed as “destroyed by enemy action.” It was never re-built and the remains of the Chapel were completely demolished in 1969.

Bibliography

Archive

Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes Archive held by the parish of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, Oxford. St Nicholas Parish Archive (SNPA).

Books

Peter Anson, The Call of the Cloister, London, 1955.

Christopher Birchall, Embassy, Emigrants, and Englishmen, New York, 2014.

Journals

Church Times, London, 1st August, 1939, 123.

J. Salter “The Sisters of Bethany and the Eastern Churches.” Eastern Churches Newsletter, 5, Autumn 1977.

South Slav Herald, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, June, 1939.

Online Resources

Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1963 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2006.

Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

Nicolas Mabin, Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbes: From the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile to the Moscow Patriarchate https://www.rocorstudies.org/2020/03/26/archimandrite-nicholas-gibbes-from-the-russian-orthodox-church-in-exile-to-the-moscow-patriarchate/ accessed May, 2020.

Николас Мабин, Архимандрит Николай Гиббс: из Русской Православной Церкви в изгнании в Московский Патриархат Published on the website Bogoslov.ru April, 2020.

https://bogoslov.ru/article/6026809 аccessed May, 2020.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_St_Barnabas accessed May, 2020

In Memory of Maria Alexeevna Nekludova. Published on the ROCOR Studies website, April, 2020. https://www.rocorstudies.org/2020/04/09/in-memory-of-maria-alexeevna-nekludova accessed April, 2020.

https://www.northumbria.ac.uk/media/7245181/daniel-harold-russian-exiles-in-britain.pdf accessed July, 2020.

http://www.rodzianko.org/english/life/ accessed June, 2020.

http://zinarohan.squarespace.com/family-article/ accessed June, 2020.

Acknowledgments

In writing this paper, I am indebted to many people who offered kind assistance, especially:

- Archpriest Stephen Platt

- Archpriest Mark Burachek

- Deacon Andrei Psarev

- Andrei Rodzianko

- Dr Alexei Koloydenko

- Edda Kornhardt

- Hanna Brightman

- Julia Brocklesby

- The Revd Margreet Armitstead

- Nicholas Knupffer

- Mark Smith https://www.seat61.com/

- Mary Steele

- Peter Thorpe, National Railway Museum, York.

- Walker Thompson

- Zina Rohan.

References

| ↵1 | In the 1930s, what we now call ‘The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia’ was known in the UK variously as the ‘Russian Orthodox Church in Exile’ or the ‘Karlovci Synod’. The church adopted the name ‘Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR)’ in 1950. In this paper I will use the name ‘Russian Orthodox Church in Exile’; using the name ‘ROCOR’ in this context would be anachronistic. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | A tribute to Maria Alexeevna Nekludova, compiled by the present writer, may be found here: In Memory of Maria Alexeevna Nekludova. Published on the ROCOR Studies website, April, 2020. https://www.rocorstudies.org/2020/04/09/in-memory-of-maria-alexeevna-nekludova accessed April, 2020. |

| ↵3 | http://zinarohan.squarespace.com/family-article/ accessed June, 2020. |