Preface

The idea to publish a Life of the Ever-Memorable Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore) was first conceived in 2012 in the months leading up to the 20th Anniversary of his repose. It was prompted by a sense of gratitude to God for the inspiring life of Fr Lazarus whose missionary endeavours and simple, burning love for Christ touched people across the globe: from Alaska to India, from Australia to Serbia and from England to Jerusalem. Most notably for Orthodox Christians in this country, his words and example were to have a profound influence on the conversion and formation of His Eminence Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) and the Ever-Memorable Archimandrite David (Meyrick) of the St Seraphim’s Brotherhood in Walsingham, as well as other clergy and laity too legion to mention.

The decision to publish this Life was also prompted by the realisation that, due to the vicissitudes of modern publishing and questionable perceptions of ‘proper’ liturgical English, as well as the shadow of controversy which so enveloped his latter years, Fr Lazarus’ rich literary legacy for today’s Orthodox Church remains largely under-valued or entirely unknown. Thus, to this day, a plethora of translations of liturgical, scriptural, patristic and theological writings remain unpublished in their original frail, typewritten manuscript form. Moreover, for many of today’s generation of Orthodox converts as well as the large numbers of Orthodox Christians who have emigrated to the UK since the fall of communism, the lack of any biographical account of his life continues to veil his signal place in the history of English Orthodoxy.

However, two decades on from his repose, it would seem that the tide is beginning to turn. In 2007, the Fr Lazarus Foundation was formed to raise international awareness of his life and writings, as well as to compile a full-length biography. A further milestone was achieved in 2009 with the publication of An Extraordinary Peace: St Seraphim Flame of Sarov by Anaphora Press, which has been explicitly identified as the authentic work of Fr Lazarus.[1]A further reference in the Garth Moore correspondence confirms without doubt that Fr Lazarus was the author. With characteristic humility he writes on Easter Day 1957, ‘I translated & … Continue reading

Owing to the formative role of Fr Lazarus’ spiritual son, Archimandrite David, in the foundation of the St George Orthodox Information Service (SGOIS), for the past forty-four years, it has endeavoured to ensure that as many as possible of Fr Lazarus’ translations and writings are in print and available to the Orthodox faithful. Following the major revision of Fr Lazarus’ translation of the Jordanville Prayer Book in 1986, and with the permission of His Eminence Metropolitan Laurus, SGOIS became the only international publisher and distributor of Fr Lazarus’ original translation. From the sales of the facsimile copy of the 1960 Jordanville Prayer book in the intervening years to Orthodox Christians across the world, it is clear that the spiritual appetite for Fr Lazarus’ liturgical translations is growing, as his distinctively direct and unpretentious style becomes more widely appreciated.

SGOIS, now serving as the distribution arm of the newly founded College of Our Lady of Mettingham, is thus delighted to honour Fr Lazarus’ memory with the re-publication of Fr Andrew Midgley’s obituary, first serialized in the pages of Orthodox Outlook in 1993. Charged with the insights of his own personal acquaintance with Fr Lazarus, Fr Andrew gives a colourful and compelling account of this extraordinary ‘English Archimandrite’ – a remarkable achievement given the dizzying array of cultures that his subject’s life encompassed, as well as the lack of access to vital biographical records.

In this re-print of Fr Andrew’s obituary, the College has attempted to produce a faithful and unified rendering of Fr Andrew’s original narrative, keeping editorial redactions to a minimum. However, following original research into hitherto unpublished correspondence about Fr Lazarus held in Lambeth Palace and Canterbury Cathedral, as well as liaison with the Fr Lazarus Foundation and historical authorities throughout the world, certain factual errors in Fr Andrew’s text and chronology of events have been corrected. We hope though that we have enhanced his original text further through the inclusion of detailed endnotes as well as a chronology for readers to refer to. Finally, in the appendix at the end of the booklet, we are pleased to present the very first publication of Fr Lazarus’ bold confession of the Orthodox Faith which he sent in 1936 to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Very Revd. Cosmo Lang.

The editor of the text would like to record his gratitude for the assistance and support he has received from many people across the world in this project. First of all he would like to acknowledge his profound debt for the patience, encouragement and support of Dominica Cranor, President of the Fr Lazarus Foundation, who cared for Fr Lazarus in the final years of his life and is his literary executor. We are also grateful to the assistance we have received from the archivists at Lambeth Palace and Canterbury Cathedral as well as the following individuals: Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware), Metropolitan Hilarion (Kapral), Fr Deacon Andrei Psarev of ROCOR Studies, Fr Stephen Platt, Secretary of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius, Reader Nicolas Mabin of the ROCOR Cathedral at Harvard Road London, Tina Machado of Historic Canterbury, Jackie Wilkie of the Old Aldenhamians Development Office and Proto-Deacon Christopher Henderson.

The story of Fr Lazarus is far from concluded, as there are still so many facets of his journey of Faith which remain unclear: in particular, his second time in India from the 1950s to the 1970s as well as his years in Greece and Australia. Thus if any reader of this booklet has any information, copies of correspondence or photographs relating to the life of Archimandrite Lazarus, please do get in touch with the College at the address on the back cover. The College hopes that the publication of this Life of Fr Lazarus will enable a clearer view and deeper appreciation of the catholicity of vision and unique literary and missionary legacy of this trail-blazing, lifelong pilgrim for the love Christ.

Mark Tattum-Smith (editor) College of Our Lady of Mettingham, 2014

www.mettingham.org.uk (ROCOR)

Chronology Fr Lazarus Moore (1902 -1992)

1902, 18 October Born in Swindon, England.

1907-1916

Elstree School.

1916-1919 Aldenham School.

1919-1921 University of Reading Agricultural College

1921-1926 Travelled to Canada.

1926-1930 Student at St Augustine’s College, Canterbury.

1930 Ordained an Anglican Deacon at St Stephen’s East India Docks, London.

1931 Ordained an Anglican Priest.

1932 All Saints Church, Islington, London.

1933 Christa Seva Sangha Ashram in Poone & Aundh, India.

1934 Involved with leading several retreats in Travancore with the Syrian Orthodox Church of South India (Jacobites);

Returned to the Christa Seva Sangha Ashrams in Poone and Aundh;

With the Cowley Fathers in Bombay;

Lived in seclusion with Archimandrite Andronik (Elpedinsky) in Travancore India.

1935 Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, Jerusalem;

ROCOR Synod HQ in Belgrade & Milkovo Monastery;

7 weeks at the Monastery of St Panteleimon on Mount Athos;

28 December Received by Chrismation into the Orthodox Church in Belgrade;

Ordained at Milkovo Monastery in Yugoslavia by Archbishop Theophan (Gavrilov) of Kursk.

1936-1948 Hieromonk at the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem & the Ain Karim Convent.

1948 Arab-Israeli War, one year in Transjordan.

1949 In London for a short period where he met Fr Nicholas Gibbes as well as continuing to assist with finding appropriate quarters for the displaced nuns from the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission.

1950 At the new ROCOR Synod HQ in Mahopac, New York.

1952 Sent to India in an attempt to unite the Church of the Apostle Thomas (Jacobites) with the Orthodox Church.

1957 Moved to Kotagiri, India.

1962-3 Moved to the Sat Tal Ecumenical Ashram in Uttarakhand, Northern India.

1972 Moved to Athens, Greece to the Russian Old People’s Home.

1974-1982 Moved to Cambetta, Australia; Moved to the Beth Shalom Community, Hobart; Served at St Nicholas Church, Melbourne.

1983 Moved to Isla Vista, California and assisted with bringing the ‘Evangelical Orthodox’ Communities into the Orthodox Church.

1989 Moved to Eagle River, Alaska.

1992 27 November Reposed and buried at St John’s Orthodox Cathedral cemetery in Eagle River, Alaska.

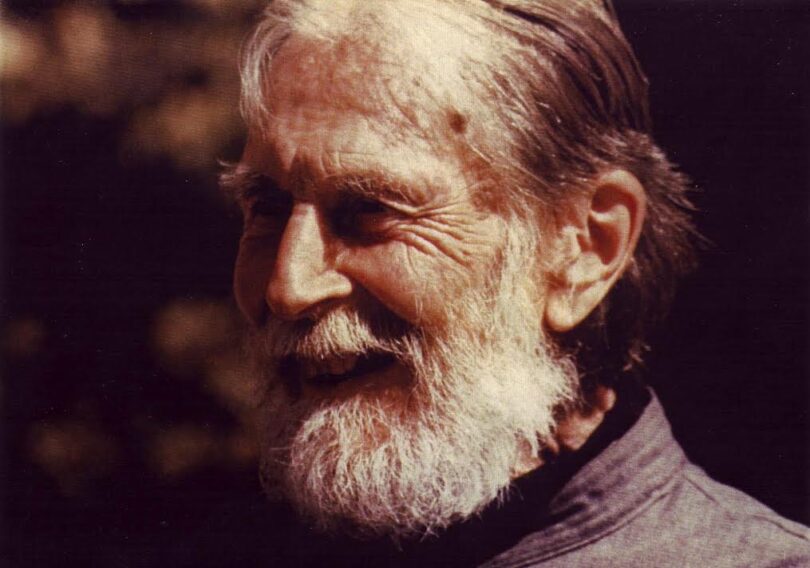

Passage to India

The Very Reverend Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore), registered at birth as Edgar Harman Moore, spent a lifetime in pilgrimage, largely in exile from his native land, rather in the tradition of the great roaming Celtic heralds of the Gospel. In his lifetime, he ranged across widely spaced corners of the globe in the service of the Lord and of the Holy Orthodox Church.

At his death, he was the doyen of all Orthodox clergy of Anglo-Saxon origins or English mother tongue. Ninety years old, he had been an Orthodox priest-monk for fifty-six years. In his final years, he had been living in Eagle River, Alaska, in the home of Deacon Harley and Dianne (Dominica) Cranor. To this house he had brought a substantial working library of books and manuscripts, but virtually no personal possessions. To the end he lived a life of apostolic poverty, a stranger and sojourner in the world, an ascetic in the midst of plenty, dead to the blandishments of the over-abundant consumer society. As ever, he ate frugally, slept no more than four hours a night, prayed much, corresponded across the world, and ever laboured at the works and thoughts of the Apostolic and Patristic writers who gave a form and record to Holy Tradition. His liturgical work will be widely known, his scriptural work perhaps less generally studied. It was as late as 1991 that he finalised his major work of translation: The Four Gospels.

When the Cranors came to his room one morning, he was found to have reposed in the Lord. That was early on Friday 27 November 1992. Firmly gripping in his hands his monastic cross, he was found gazing – by then sightless in death – at his ikons, as his soul passed through the window of the ikons to the Divine Light beyond. For some time previously, he had been suffering from terminal cancer, which first attacked his lungs but by the end was also present in his bones.[2]We are informed by Dominica Cranor that, in actual fact, the initial diagnosis was of prostate cancer, which was later found to have spread to the lungs and bones. Frail as he was, he had nevertheless managed a little walk each day, almost until the last. To the end, he loved and lived only in Christ, the Lord of Light, Risen from the Dead and Ascended into the great Glory, ever Reigning.

The catafalque was set out in the Antiochian Orthodox Cathedral Church of St John from the time of the Vigil Service of the Lord’s Day until Monday, when, at a quarter past nine in the morning, he was accorded the final rites of the Holy Orthodox Church and his body laid to rest in the burial ground of the Cathedral.

The catafalque was set out in the Antiochian Orthodox Cathedral Church of St John from the time of the Vigil Service of the Lord’s Day until Monday, when, at a quarter past nine in the morning, he was accorded the final rites of the Holy Orthodox Church and his body laid to rest in the burial ground of the Cathedral.

One tends to think of Father Lazarus as a ‘Russian’ Archimandrite, for it was within the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia that he was first received, for long laboured, and finally reposed, but in fact he had spent his declining years within the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Antioch, perhaps appropriate for an Apostle who had laboured long among Arab Orthodox, albeit living within the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem. He was, at one and the same time, a cosmopolitan ‘citizen of the world’, and a quintessential Englishman.

He was born into the prosperous world of middle-class, pre-Great War England, at Swindon, in 1902. His father had been at one time a Master of Foxhounds.[3]His father was a stockbroker on the London Stock Exchange. (I was to see many souvenirs of this epoch when I visited Father Lazarus’ widowed mother in his company in 1952; her cosy house at Beaconsfield was much adorned with hunting horns, fox’s brushes, and the like). The young Edgar was one of five sons, of whom one attained the rank of Air Vice Marshal in the Royal Air Force. He had also a married sister, Lorna, by whom he was survived and who, I believe, lived at Beaconsfield herself until recently.[4]Fr Lazarus’ five siblings are: Geoffrey Moore, Norman Moore, Martin Cedric Moore, Charles Roger Moore and Lorna Matheson. Whilst Charles and Martin were in the armed forces during WWII it has … Continue reading

The boy Edgar Moore had his schooling during the traumatic and unsettling years of the Great War, 1914-1918.[5]He began his education at Elstree Preparatory School between 1907-1916 and then moved up to Aldenham School between 1916-1919. When he was eighteen years old, in 1921, he was sent out to Canada to see something of the wider world of ‘the colonies’, and to find his feet ‘in a man’s world’. He settled originally in the rugged Province of British Columbia. He learned to turn his hand to many tasks, to be tough and resourceful. He worked as a homestead farmer and a shepherd (perhaps where he learned the life of a ‘loner’). He built up his muscles as a lumberjack in the high timber country and came to work at a later stage as a ‘longshoreman’, what we in England term a ‘docker’. He travelled across to the neighbouring Province of Alberta to gain employment as a contract harvester working the vast wheat prairies in harvest time. In due time, he applied for Canadian nationality and, one may assume, intended to make his life for good in the young Dominion. He thought himself settled in the Dominion for life. God had other plans for the young Englishman. His path lay in far stranger, more unknown and almost unimaginable parts. God suddenly branded young Edgar and summoned him for very particular and special service as minister and ascetic. He was to embark upon the twin path of ministry and asceticism as an Anglican, but to fulfil it as an Orthodox hieromonk. What inspired the attraction and call to India we do not know with any certainty. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Christian leaders began to evince genuine interest in and respect for the ancient spiritual traditions of India and of Indian culture at large. It became acknowledged widely that for Christianity to take permanent root in India it had to become a truly Indian phenomenon.

The would-be Anglican-ordinand, Edgar Moore, felt drawn to this work. Returning to England, he entered St Augustine’s College, Canterbury.[6]Edgar was enrolled at the College from 1926-1930.This college had been founded under Royal Charter in 1848 ‘for the education of young men preparing for ordination with a view to the distant dependencies of the British Empire.’ Edgar stayed there as a student for four years. Years later, Father Lazarus told me that he had undertaken a course in Agriculture at Reading University. I had assumed it to have been in preparation for farming in Canada. Clearly this scenario does not fit the chronology of Fr Lazarus’s life. Perhaps it was a small element within the overall four year period in statu pupilari at St Augustine’s.[7]The inconsistencies in the chronology are resolved in an “Oral History Paper” completed for a Sociology Class on 11 March 1986 by Stephanie Rae who interviewed Fr Lazarus about his life. … Continue reading

Young clergymen destined for the Indian Church were required to be ordained to ‘a title’, an English parish where they would serve their first apprenticeship. The Reverend Edgar Moore was ordained deacon in 1930 and served his title – first curacy – at St Stephen’s Poplar, in the Diocese of London, then presided over by Bishop A.F. Winningston-Ingram, who was Bishop of London for thirty-eight years from 1901 to 1939. In 1931, the Reverend Mr Moore was ‘priested’ and went to serve a second curacy at All Saints, Islington.

Fr. Lazarus first placement after he was made a priest in the Anglican Church was in All Saints Church in Islington, London 1932

In 1933 Edgar Moore, at the age of thirty-one, took passage to India and definitive entry upon the ascetical way of life which, whilst it may have been varied across the years, was never surrendered. The monk was emerging within the Anglican clergyman. He travelled to Poone – the Poona of Anglo-Indian legend – but not to become a ‘Poona Sahib’, but a Christian Ashramite. He went there to join an English-Indian Christian community in process of establishing its special character as, effectively, the first and foundational Christian Ashram. It was a Society of Christ’s Servants, or Christa Seva Sangha (Christian-Service-Society). It was not intended to be the instrument of inter-faith dialogue but as a vital initiative towards establishing a genuine indigenisation of the universal Gospel into the very heart of India. The founder and first Acharya (Superior or Sahdu-Guardian) was a Balliol man, the Reverend John (Jack) Copley Winslow, who underwent his theological training at Wells, had been a lecturer at St Augustine’s and had himself gone to India under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG). Apart from the traditional type of monastic communities, both Roman Catholic and Anglican, there were various other experiments in Anglo-Indian communal living being explored by Anglicans and others. Other Christian Ashrams were to follow and the work of the Roman Catholic Benedictine, Dom Bede Griffiths, was to make the Ashram mode of spiritual pilgrimage quite widely known in Britain. Although Father Edgar was not to stay long at Christa Seva Sangha, the inspiration and influence of the Ashramite way can ever be detected at a deep level in the unfolding spiritual life of our beloved Fr Lazarus to be.

Anglican Ashramite to Orthodox Hieromonk

There may be five million Indian Christians whose faith, directly or indirectly, derives from the Apostolic Tradition of the Church of St Thomas. Today, the majority of these believers acknowledge the Bishop of Rome as their Chief Hierarch. But at least one and a half million Christians in India still remain loyal to the ancient Syrian Orthodox Church,[8]According to a recent survey, this number now stands at approximately 2,100,000. an Autocephalous Church under its own Catholicos and rendering to the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch respect broadly similar to that accorded in the Byzantine Orthodox Church to the Patriarch of Constantinople.

The term Ashram is commonly employed in the indigenous Indian Christian community to describe centres in which the ascetic path is pursued in varying degrees of – in Western terms – ‘strictness’. A monastery, easily recognisable as such by Westerners, is an Ashram, but the term may be applied to a centre much freer than a traditional monastery in its hold on its members. Indian Christian ascetic life may often be compared more closely with the variegated forms of Syrian monasticism in the pioneering period. The Ashram which the Anglican Father Edgar Moore joined was not a Syrian Orthodox community but an officially commissioned Anglican centre. However, it was, to some degree, influenced by the traditions of the ancient Indian Church. For example, it used a form of Eucharistic Liturgy based upon the East Syrian Rite. This Liturgy was published by Longmans under the title An Order for the Administration of Holy Communion Sanctioned by the Episcopal Synod of India for Experimental Use in the Diocese of Bombay.[9]The ‘Bombay Liturgy’ is similar to the Orthodox Liturgies of Sts Basil the Great and John Chrysostom in several respects through the insertion of the Trisagion, litanies pronounced by the … Continue reading The story of the Anglican Ashram to which Father Edgar Moore adhered was published in 1930, by the SPG, entitled Christa Seva Sangha by the Founder Acharya (Superior), the Reverend John (‘Jack’) Copley Winslow. The Ashram started at Miri in 1922 when it had one Englishman (the Founder) and five Indians as members. By 1930, the community had grown to twenty members, half of whom were Indian. The community moved from temporary home to temporary home until it established a stable base in Poone (Poona), on five and a half acres of land outside the city, where they erected their math (Enclosure). In 1928, the Anglican Bishop of Bombay professed Fr John Winslow as the first Siddha (later termed Sannyasi) – professed Brother – of the community. Their simple Rule was directed at the fulfilment of bhakti, devotion, to the Lord Christ. The life was founded upon prayer and sacred study. They also exercised an active vocation of service to the sick and suffering amidst a life of Apostolic Poverty. Members of the community used the ground for lying and sitting. Their ‘bed rolls’ (mats) they unrolled on the verandah. Their food was exclusively vegetarian.

The Ashram movement is many-faceted. The original (and classical) Ashram was (and is) explicitly Hindu and an integral manifestation of Hindu spirituality. But there are Buddhist Ashrams and many ‘Ashrams’ established by modern Indian false prophets, some self-deluding, and others explicitly established by charlatans to attract (especially Western) people for the economic advantage of the false and sometimes quite evil Sadhus. The ancient Sadhus were serious spiritual seekers who retired into the forest as solitaries seeking enlightenment. Like the great monastic founders in medieval Christian society, they so often failed to preserve their solitude, as would-be disciples made their way to their simple retreats, wishing to sit at their feet to learn the spiritual path. The Sadhus thus became Rishis, spiritual adepts and guides. Sometimes, these communities dissolved on the death of the Founder; in other cases, an ‘Elisha’ succeeded an ‘Elijah’.

The Western commitment to the Ashram tradition is a very basic act of self-abasement. It constitutes a denial of European superiority and an acceptance of the right to recognition and respect on the part of Indians and of the ancient spiritual traditions of India. Such humility is a rare quality among Europeans, especially Englishmen. A real and serious danger is the dilution of the Christian Gospel by a species of eclecticism. The primary heretical stance which may arise in indiscriminating dalliance with non-Christian faith communities and traditions is that which accords equal validity to all (certainly all major) religions. Such a proposition is inconsistent with the Gospel of Christ and the Tradition of His Orthodox Church. The Christian can be too humble, not so much on his own behalf, but on behalf of the True Revealer of Religion, the Lord Jesus Christ, in the way in which he engages in dialogue with those of other Faiths. The dangers should not dissuade the Church from such enterprise, but it is not a vocation for the spiritually immature or theologically unsophisticated. (This effectively became the life’s work of the great Dom Bede Griffiths; who had begun a deep study of Indian philosophy and the Hindu scriptures whilst Prior of the new Benedictine foundation at Farnborough. In 1958 he went to India and became, from the outset, committed to the Indian ascetic tradition of sannyasa, the life of utter poverty and total abandonment to the Spirit.)

Fr Edgar Moore did not find his path to lie with an Anglican Ashram, nor with too deep an exploration of Hindu thought, although he was not entirely untouched by it, which rendered some of his thinking distinctly disturbing to the traditionally minded Orthodox Christian; e.g. as regards the condition of the Christian’s eternal life in God in terms of the loss of individuality in ‘the One’. How long he remained with Christa Seva Sangha is not altogether clear.[10]Fr Edgar arrived at the Ashram on 10 June, 1933. He remained there almost exactly a year, leaving in June of the following year. In Canada, he had been used to hard living; life in the Ashram introduced him to the realities of total voluntary poverty. It was an important medium whereby the unconscious racism of an English ‘Colonial’ was completely expunged from his psychic make-up. From thence forward he was indifferent to race or colour as a means of distinguishing God’s children. It introduced him to Eastern Christian ways of worship and, at least to some degree, to Indian psychic and spiritual categories of thought, virtually devoid of that reek of dualism against which Dom Bede so passionately inveighed. To have been an Ashramite was to have embarked upon the spiritual quest in a very special way for a European, even for one destined for the Orthodox Church. But an Anglican Ashram failed to satisfy his deepest aspirations. Not without much soul-searching he decided to tear himself away and pursue his quest elsewhere. He left Poone and journeyed south to Travancore, today encompassed within the State of Kerala. There he did not seek to associate himself with a Syrian Orthodox Ashram, of which there were probably, even then, a number from which to choose.[11]Actually, Fr Edgar had made contact with the ‘Syrian Orthodox Church’, through accepting invitations to lead retreats in Travancore in January 1934. (cf. Letter from Edgar Moore to the … Continue reading Instead, he sought out a Russian Orthodox monk of whom he had heard, Archimandrite Andronik (Elpedinsky) (1894-1958),[12]Archbishop Anastassy advised Fr Edgar to seek out and live with the nearest Orthodox priest. He stayed with Fr Andronik from October 1934 to May 1935. Fr Andronik later went on to become the rector … Continue reading who was about ten years his senior. Fr Andronik was one of the vast army of Russian refugees spewed out of the ferment of Revolution and Civil War in the disintegrating Russian Empire. He had fled from Russia in 1920, finding refuge first in the Germany of the Weimar Republic and subsequently in France. He had been a pre-war seminarian at Petrozavodsk, from whence he had set out to fight in firstly the Great War (1914-1918), and subsequently as a volunteer in the White Army in the Russian Civil War (1918-1920).

The Russian Student ChristianMovement (SCM) in Exile became intimately involved in the establishment of the – ultimately world-famous – Orthodox Theological Institute of St Sergius in Paris. The young veteran Elpedinsky was very active in the SCM and came forward to enrol at the newly-founded institute on what was probably the very first course, which opened in April 1925. The preparatory course was completed by the autumn of the same year, and in the November, Fr Andronik took monastic vows, was ordained, and began six years of service as a parish priest in the Russian Emigration until 1931, when he went to India. He was to stay there for eighteen years, until, indeed, the age of fifty-five, when he emigrated to the United States of America there to pass the rest of his life. He reposed in 1958. An account of his life in India, entitled Eighteen Years in India, was published posthumously in Buenos Aires in 1959.

In India, Fr Andronik settled upon a hill in the countryside of Travancore, devoting himself to toiling in collaboration with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. He yearned for the day when the ancient Church of St Thomas the Apostle would be restored to communion with the other apostolically founded Churches in fellowship with Constantinople. Many years later, Dr Nicholas Zernov was to devote a substantial period of time to theological and historical teaching at the same Indian Orthodox Theological Seminary. It had been founded at Kottayam in 1815 and has remained the central theological institution of the Malankara Church ever since. This College over the past 178 years[13]The College is still open at the time of writing in 2014, and must therefore be nearly approaching its 200th Anniversary. has given outstanding service to the ancient Church of India in greatly elevating the theological knowledge and articulation of the whole body of the clergy.

Fr Lazarus once told me that he was converted to Orthodoxy by reading a book, one of the works of Dr Zernov.[14]It is still a mystery as to which book by Zernov could have so inspired Fr Lazarus. This impressed itself upon my memory because his was the only instance of which I have had direct knowledge of a man having changed his religion as a result of reading a book, other, that is, than the Holy Bible. I do not recall, if indeed he told me, which of Dr Zernov’s books it was. In any case, there is some difficulty in the matter, for none of Nicholas Zernov’s books appears to have been published in an English edition quite early enough to meet Fr Lazarus’s chronology, unless Fr Andronik were to have read it (and translated it) to him from the Russian edition. At all events, the time spent with Fr Andronik served to define a very specific chapter in Fr Lazarus’s spiritual and ecclesial evolution. His sojourn in Travancore served to bring him into intimate association with Russian Orthodoxy and Russian asceticism. Together, the Russian monk and the erstwhile Anglican Ashramite lived a life of very real asceticism, sustaining themselves, according to Fr Lazarus, on roots, berries and such food as the local Indian villagers brought them in offering to the Christian Sadhus. From boulders and smaller stones strewn around on the ground around their hermitage, the two ascetics managed to construct and fashion a little oratory, in the shelter of which Fr Andronik was enabled to celebrate the Divine Liturgy and in which they conducted the Divine Office. In association with the labours and fraternal associations of Fr Andronik with the Indian Orthodox, the future Archimandrite Lazarus developed a close acquaintance with the theological and liturgical traditions of the non-Chalcedonian Indian Church.

Because Fr Edgar was not an Anglican layman but an ordained man, Fr Andronik was precluded by Church law from receiving him into Orthodoxy. At that time he could only be received by a bishop. However there was no Byzantine[15]Either a Russian or at least canonically Orthodox Bishop. Orthodox bishop in all the Indian sub-continent. The two companions laboured on together as best they could in the sadness of being out of sacramental communion with each other. And then God intervened to arrange the cutting of the Gordian knot. An ‘anonymous lady’, almost certainly the future Abbess Maria of Gethsemane (Miss Robinson at this time), a lady blessed with considerable financial resources, sent to Fr Edgar sufficient funds to enable him to travel to the Holy Land to seek admission into Holy Orthodoxy at the hands of the Patriarch of Jerusalem. This apparently simple proceeding proved to be encompassed by hazards and stumbling blocks. This is not, perhaps, the proper occasion to recount in full the official Anglican lack of charity and compassion in the 1930s towards all Anglicans, particularly any in Holy Orders, who wished to be admitted to the Orthodox Church. This amounted to blatant persecution. This policy derived from Lollards Tower at Lambeth Palace, home of the recently established Council of Foreign Relations. From most Anglican bishops and the great majority of Anglican priests, such pilgrims met only sympathy and moral support. The malevolence directed against the would-be Orthodox was quite absent in official attitudes towards those who ‘trod the Primrose Path to Rome’. The reason for this attitude was the Anglican lack of self-confidence, combined with an urgent desire for ‘recognition’ by the non-Roman ‘Catholic’ Churches. It was hoped that the Eastern Churches would give ‘recognition’ to the Anglicans’ orders and their sacraments. For them ‘valid’ sacraments were all that was required to make a ‘valid Church’. Therefore nothing could be allowed which threw doubt on the validity of these aspirations. The arch-manipulator who sat, like some monstrous black widow spider, in the far-from-Ivory tower at Lambeth Palace, was Secretary of the Church of England Council for Foreign Relations, Canon J.A. Douglas, a Machiavellian ecclesiastical diplomat conspiring across the ecclesiastical world. Fr Edgar Moore’s simple request – which became a quest – to gain admission to the Orthodox fold began to appear as unlikely of success as for an army mule to run in the Derby.

His case, as was that of two Scots ladies (to whom we shall refer shortly), was inopportune in presentation and embarrassing, both in character and consequence, in the eyes of both Anglican Orthodoxophiles and Orthodox Anglophiles alike. Anglican Orthodox relations were enjoying a golden noontide, as never before achieved nor ever again realised. There were many on the Anglican side, and not few on the Orthodox, who had come to believe that actual union, or at least some substantial form of ‘intercommunion’ (a notion dear to the Anglo-Catholic ecumenists of the period), stood at the threshold of realisation. The situation was delicate, virtually hair-trigger, or so the optimists supposed. Nothing must be allowed to rock the boat as it sailed cautiously into harbour. The critical issue in Anglican eyes was the one which had already dealt a death blow to all hopes of Anglican-Roman Catholic union: the authenticity of Anglican orders, the lack of which would, so Anglo-Catholics believed, destroy all Anglican pretensions to being accounted truly a ‘Church’ and a legitimate ‘Branch’ of the One Church Catholic. Would the Orthodox Church, as a whole or individually, give form to isolated statements of recognition by admitting an Anglican clergyman into Holy Orthodoxy ‘in his Orders’, i.e. as a true priest, (even if by economy), without any sort of re-ordination? In their bones, the Anglican negotiators must have known that the response would be negative; they desperately schemed to prevent it being put to the test.

Close amicable, indeed fraternal relations had been brought to fruition between the two Communions. The Orthodox Churches, faced with manifold political and economic difficulties, were eager to enlist the aid, both moral and practical, of the Anglican Church. The Anglicans were anxious to gain recognition from the Eastern Churches in order to counteract the disastrous outcome of the Malines Conversations which resulted in the Papal Encyclical of Leo XIII, condemning Anglican ‘Orders’ as null and void. In 1925, there had been a great commemoratory celebration in England of the 1,600th anniversary of the Council of Nicea to which most of the Orthodox Churches had sent official delegations, and a very comprehensive pan-Orthodox delegation attended the Anglican Lambeth Conference in 1931. This was followed by an Anglican-Romanian Orthodox Conference in Bucharest in 1935. The ship of Anglicanism appeared to be sailing with a fair wind to safe haven and the fulfilment of the highest hopes of the historic Anglo-Catholic (High Church) party.

Apart from the inappropriate timing of Fr Edgar Moore’s presentation, attempts to enter Orthodoxy by way of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem were doomed to frustration. There were historical reasons for this. Western missionary enterprise in the Holy Land, from the 12th Century onwards, be it ‘Latin’ or Protestant, started with the intention of converting the infidel Moslems to Christianity. However, almost immediately in the face of the Islamic law that prescribed death as the penalty of conversion it became deflected from evangelisation of non-Christians, to proselytism among the faithful of the Orthodox and Oriental Churches, to the considerable hurt of both. When, in consequence of a joint British-Prussian initiative, an Anglican-Lutheran Bishopric was set up in 1841, the work of enticing Orthodox believers into Anglicanism proceeded apace. The small Anglican community today, comprising 3,800 faithful in Israel, Jerusalem and the West Bank, and 2,000 in Jordan,[16]There are now approximately 7,000 Anglicans served by the Diocese of Jerusalem. are almost all descendants of Orthodox forbears who were induced to leave Orthodoxy for Anglicanism in the last century. (Similarly, approximately 63,000[17]There are now approximately 55,000 Melkite Catholics in Palestine. Melkites are of Orthodox descent, although many of them are, in fact, more Orthodox than Catholic in sentiment.) From the occupancy of the Anglican Bishop Barclay (1879-1886) of the See of Jerusalem there was an interregnum. With the appointment of Bishop Popham-Blyth in 1886, the Anglican attitude underwent a fundamental change. A rapprochement between the Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem and the Patriarch of Jerusalem gave rise to a new mutual understanding against ‘soul poaching’ on the part of either ecclesiastical authority.

Fr Edgar Moore encountered this in its practical effect when he sought to join the Greek Church in Jerusalem. Greek Orthodox and Anglicans combined to make this consummation of the English-Canadian monk’s deepest hopes impossible of achievement. The complexities of the Anglican ‘anti-conversion’ machinations and the impressive and depressing groupement of Anglican dignitaries drawn into the virtual campaign against Father Moore, makes tedious and sad reading. (I was, much later, in the 1950s, to encounter the same sort of obstacle when I sought to join the Archdiocese of Thyateira. Bishop James (Virvos), as he then was, said that the Archbishop (Athenagoras I) would not permit any of the Greek clergy to receive Anglicans, because he had himself been appointed specifically by the Ecumenical Throne to be the personal Apocrisarios to the See of Canterbury. I was advised to seek entry to Orthodoxy by way of the Russian Church.)

In the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, no priest, even from another Orthodox Church, can be admitted as a priest of the Patriarchate except by the decision of the Holy Synod itself. Certainly, any decision to admit an Anglican clergyman, whatever the decision about the admissibility of his Orders, would not have been one to be taken lightly. To complicate the matter there existed a hiatus in the Jerusalem succession between 1931 and 1935. In the interregnum, Archbishop Meliton of Madeba functioned as locum tenens of the Patriarchal Throne, but it may well have been the case that the most influential figure in the Holy Synod was His Grace Archbishop Timotheus (Themetes) of the Jordan, who was to ascend the Patriarchal Throne in 1935 and to occupy it for twenty years. He had been one of the delegation which came to England in 1925 and had become both strongly Anglophile and a warm admirer of the Church of England. He was certainly not one to encourage the reception of Anglicans overtly and probably not covertly either. Salvation for Fr Edgar Moore lay elsewhere than chez les Greques; it was to be found at the Russian hearth, through the mediacy of the Russian Palestine Mission, headed, at that time, by the redoubtable Archbishop Anastassy (Alexander Gribanovsky, 1873-1965).

The Years of Orthodox Mission

The Russian clergy and monastics serving in the Holy Land and composing the Russian Mission operated under the auspices of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society founded in 1882 by the Grand Duke Sergei, husband of the new saint, Grand Duchess Elizabeth, as the culmination of initiatives begun by Peter I and greatly accelerated in the period before and after the Crimean War (1855-56). They existed to care for the Russian pilgrims coming to the Holy Land in vast numbers from 1841 to 1917 and to give aid to the Arab Orthodox. After the Bolshevik subjugation of the Russian Church in the Motherland, the Russian Mission in Palestine passed under the jurisdiction of the Russian Church in Exile. After the defeat of Turkey in the Great War, Palestine passed into the temporary care of Britain who received a League of Nations Mandate to administer it.

Three British converts were to give distinguished service to Orthodoxy during the Mandatory period. They were Miss Mary Robinson, the future Igumena Maria of the Convent of St Mary Magdalene, Gethsemane, the gilded cupolas of which are familiar to every pilgrim and visitor to the Holy City; Miss Sprott, the future Mother Martha of Bethany, and the Reverend Edgar Moore to become the Very Reverend Archimandrite Lazarus. The then Anglican bishop in Jerusalem did his best to dissuade the two determined Scottish ladies from embracing Holy Orthodoxy and urged his friend and ‘brother-in-Christ’ Archbishop Timotheus (Themetes) of the Jordan (then the most influential member of the Jerusalem Greek hierarchy) to set his face against receiving them. The best friend of these would-be British Orthodox proved to be the Russian Archbishop Anastassy (Gribanovsky, 1873-1965), head of the Russian Mission in Palestine. This wise and adroit prelate resisted Anglican pressures and circumvented the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate’s compliance with the provisions of the Anglican-Greek ‘protocol’ (designed to halt mutual proselytism between the two bodies) by arranging for the two ladies to journey to Syria where, in Damascus, the Arab Patriarch Alexander III (1931-1958) of Antioch received them by Chrismation. They then returned to Jerusalem to be clothed as monastics. As Mother Mary and Mother Martha they laboured at Bethany, where the school founded by the Russian Mission built up a high reputation, being patronised by Orthodox Christian families, not only from Palestine but also from adjacent lands like Transjordan. Other girls and orphans were cherished and taught at the Convent of Mar Zakarya in the home village of St John the Forerunner, Ain Karim.

As Igumena, Mother Maria was to preside over a community of numerous nuns at the Convent in Gethsemane. Among them was the Igumena Elizaveta (Mother Elizabeth Ampernoff), professed at Gethsemane in 1939, Igumena of Mar Zakarya until forced to flee to Jordan in the upheavals of the Arab-Jewish War of 1947-8. She fled in the wake of the British evacuation with Mother Seraphima and a number of young Arab novices. They subsequently found refuge in England, eventually establishing a monastic house in Brondesbury Park, near Kilburn. Mother Maria organised the school at Bethany and opened a free Medical Clinic there. When this splendid servant of the servants of God reposed in 1969, it became known that she had maintained both the Gethsemane Convent and the Bethany School at her own expense for ever thirty-five years, with an annual budget of £14,600.

Father Lazarus had been serving as Chaplain at Ain Karim when the need to flee the victorious Israeli Army came suddenly upon the Community. Not all fled – indeed the majority remained. In the confusion, Fr Lazarus was only able to retain his passport, all else was lost; and thus it was that in later years he had to rely on his memory to furnish key dates in his life. He recalled that he spent seven weeks on Mount Athos, but whether this preceded or followed his entry into Orthodoxy, and whether indeed this took place before his initial journey to Palestine (or en route) or on his way to Serbia from Palestine, remains unclear.[18]We now know this visit took place in 1935. Father Lazarus stayed at the Holy Monastery of St Panteleimon on Mount Athos with Fr Winslow. This is detailed in a letter dated December 1935 from the … Continue reading

In the face of implacable opposition on the part of both Anglican and Jerusalem Greek Orthodox authorities towards the projected reception of the Reverend Edgar Moore into Orthodoxy, the resourceful Archbishop Anastassy remained undismayed and arranged passage for the Anglican clergyman to Serbia where the Synod of Russian exiled bishops had its Seat at the hospitality of the Serbian Patriarch. Canon Douglas, another resourceful cleric, used every means open to him, ecclesiastical and diplomatic, to try to prevent the reception of this lone person. He failed. The Anglican cleric was welcomed into the Orthodox family, but not as a clerk in Holy Orders.

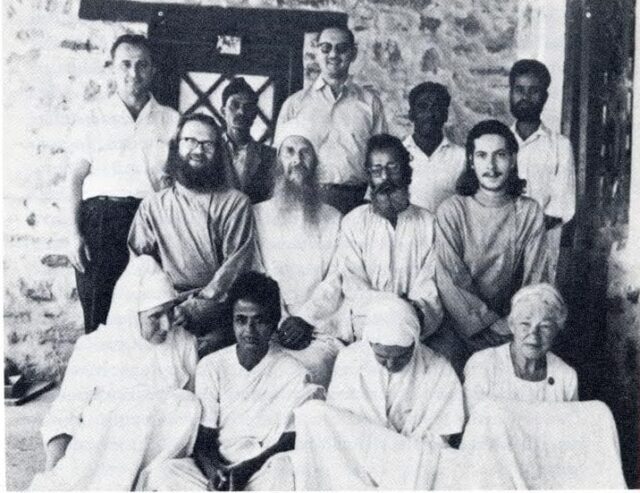

Father Lazarus and Abbess Elisabeth (Ampenov) on the left with sisters of Gorny Convent remainded with ROCOR. Transjordan 1948-49

The English Orthodox neophyte embarked [in 1934] on a year of testing in obedience to the command of the great Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky, 1861-1936), formerly of Kharkov and later of Kiev and Galicia; who had himself been the leading candidate in the elections for the restored Patriarchal office held during the Great Sobor of 1917 and at this time presiding as Chief Hierarch over the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. Metropolitan Anthony was warmly disposed towards the young former Anglican and, on welcoming him back from India, authorised his ordination. Fr Lazarus was ordained in December 1935 by Archbishop Theophan (Gavrilov) of Kursk at the Serbian Orthodox monastery of Milkovo.[19]Fr Lazarus told Dominica Cranor that Archbishop Theophan made him a deacon, and then a priest one week later, on 28 December at Milkovo Monastery in Yugoslavia. The ordination was claimed to have been with the blessing of Patriarch Varnava of Serbia (1930-37).[20]It would seem, at least from the archival record, that the ordination of Father Lazarus did not carry the explicit blessing of the Serbian Patriarch Varnava. This is stated in a letter from Irenei, … Continue reading

The ordination of the new Hieromonk Lazarus (Edgar’s monastic name in Orthodoxy), following relatively soon after the reception and monastic clothing of the two Scottish ladies, served to cast something of a blight over the hitherto seemingly harmonious progress of Anglican-Orthodox relations. The event, apparently of trivial importance in itself in terms of inter-denominational relations, was in reality of very great (even, for the Anglicans, shocking) significance, for it served to underscore the fact that the Orthodox Church, however harsh the political and economic circumstances in which it found itself, retained its essential integrity and steadfastness of resolution in adhering to Holy Tradition. Much as it needed Western ecclesiastical, political and practical support and aid, it would not sell its birthright for a mess of pottage. When it came to the point, the Lazarus incident demonstrated that, actively or passively, three great Patriarchates, Antioch, Jerusalem and Serbia, concurred in the course of action initiated by the Exiled Russian Church: to be willing to receive genuine converts from Anglicanism, to admit them to the Angelic Order and to require former Anglican ministers to submit to Orthodox Ordination if they were to serve in the Orthodox Church as presbyters.

It has to be emphasised that Metropolitan Anthony did not initiate action solely on his own august authority. The Synod passed a formal resolution on the case which stated:

Considering as obligation the practice of the All-Russian Church and particularly the precedents in America when the Patriarch Tikhon was there as Archbishop, Edgar Moore must be re-ordained in the Orthodox Church.[21]c.f. “The Case of Father Lazarus Moore” in the Glastonbury Bulletin No. 65, November 1982, p.143 et seq.

The importance of the Lazarus case, is that it provided a timely public re-assertion of the formal Orthodox position vis a vis Anglican orders, not as exercised within Anglicanism, but as potentially to be exercised within Orthodoxy. They are already so questionable that, even without the apostasy of female ordination, the appropriateness of applying economy to any Anglican cleric reconciling with the Church is a matter of extreme dubiety, and should always be avoided. Following his Orthodox presbyteral ordination, Fr Lazarus was assigned to the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem. He was to labour for fourteen years in the Holy Land.[22]Technically Fr Lazarus laboured in the Holy Land for 13 years, from 1935-1948. He then worked for a further year from 1948-1949 in the Transjordan.

In 1936 Metropolitan Anthony died, to be succeeded by Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky), who was to preside over the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia until 1964, reposing in 1965. He continued to have benevolent regard for Fr Lazarus throughout his long tenure of the highest office of the Synodal Church. Metropolitan Anastassy, whilst undeviatingly loyal to the most positive tenets and practices of the conservative modes of historic Russian Orthodoxy, was a hierarch of considerable breadth of vision and depth of understanding. Certainly, few senior Orthodox hierarchs, apart from his friend and fellow prelate, the saintly[23]St John was officially glorified in 1994 by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. Archbishop loan (John) (Maximovitch) of Shanghai and San Francisco, have exhibited so great sympathy and imaginative understanding of the problems and aspirations of Western Orthodoxy.

During his long years in the Holy Land, Fr Lazarus both steeped himself in Russian Orthodoxy and sought to search out the spiritual treasures of the Fathers of the desert. With his tall lean figure, patriarchal beard and long head-hair like a Nazirite, but curled up in a monastic head bun, deeply grooved face of a texture between vellum and parchment, his quiet dignity and modest demeanour, he was the very embodiment of the age-old Orthodox monastic prototype. He devoted time both to Bethany and Ain Karim, but his duties lay principally at Ain Karim where he served as chaplain to the numerous community of some one hundred nuns. Some of the girls, orphans and others, cared for at the Convent, responded to the monastic vocation, but others found their destiny in marriage; not a few sought marriage to members of the British garrison. The would-be bridegrooms were summoned for interview by the Igumena. Fr Lazarus used to recount amusing stories of red-faced young British Tommies in khaki drill order with sunburnt knees, sitting with their caps in hand in the cool waiting hall of the Convent, nervously awaiting the summons of the Igumena. Fr Lazarus was sometimes to be found sitting in that hall when a nervous soldier would slowly, pronouncing each word separately, address him: ‘Excuse me, Father, but…do…you…speak…English?’, only to find himself, to his astonishment, being responded to in what used to be termed ‘Oxford English’.

During the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the Israelis commandeered the Russian Compound as Military Headquarters; it remains in Israeli Government hands,[24]In 2008, the Israeli Government returned a 9-acre plot – Sergei’s Courtyard, named after the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich – to Russia. in part housing the ministry concerned with religious cults. At the end of World War II, the Patriarchate of Moscow established a Department of External Church Relations, the first Chairman of which was the famous Metropolitan Nikolai of Krutitsky and Kolomna (1946-61). He had been born Boris Yarushevish in 1892 and had himself received the monastic habit at the hands of the future Head of the Church in Exile, Anastassy, in 1914. He had been a bishop since 1922. He died in 1962. On assuming responsibility for foreign relations on behalf of the Patriarchal Church, Metropolitan Nikolai embarked on a world-ranging mission having as its object the recovery of the various provisional jurisdictions of the Russian Church outside the political reach of Soviet Power. The Soviet Secret Intelligence Service, the NKVD, was not slow to associate itself with his operation- indeed it may well have inspired it – and much unrest and uncertainty (including in Palestine, murders and threats of murder) took place, although none but those who lacked all powers of discrimination attributed these to the Metropolitan himself, even to the extent of inspiration. Fear was generated in the Russian Emigre communities. The situation was especially sensitive in the Holy Land because Soviet Foreign Policy had serious designs on the new State of Israel which it hoped to make its satrap. Accordingly, the USSR was the first Foreign Power to recognise the State of Israel and, as part of the initial quid pro quo, the Israeli Government accorded the Moscow Patriarchate legal authority to acquire the properties of the Russian Mission in the Holy Land. That is how it was that the Moscow Patriarchate acquired the Convent at Ain Karim, from which Fr Lazarus and those nuns who, with Mother Elizabeth, refused to submit to Moscow, fled so precipitately to the refuge of the Kingdom of Jordan, travelling on eventually to London.[25]The details of this are recorded in Fr Lazarus’ correspondence from the Holy Land with his cousin, Evelyn Garth Moore (Garth Moore Papers). Of course, the expropriation of mission property was not effective in East Jerusalem, Jordan, and Jordan-held territory, and by the time Israel had come to extend its occupation over all the Holy City and beyond, relations with the USSR had soured and properties like the convents in Gethsemane and the Mount of Olives were allowed to continue unmolested in the care of the Russian Synod.

Since first publication in Madras in 1970 this translation of St. Ignatius Brianchaninov’s classics has survived a number of edition. On the photo the latest available from holytrinitypublications.com

When Fr Lazarus returned to London, he served a small English Orthodox group which had formerly been in the care of Fr Nicholas Gibbes. Charles Sydney Nicholas Gibbes (1876-1963) was a Yorkshireman who had been the devoted tutor of the heir to the Russian Throne, the young Grand Duke Alexei, swallowed up by the Bolshevik Revolution. Sidney was tonsured a monk as Fr Nicholas in 1934, and ordained a priest in 1935, becoming an Archimandrite in 1938. He used to serve the Divine Liturgy in a privately owned Chapel in Bayswater Road which unfortunately sustained major bomb damage in an air raid during the Second World War. The site was subsequently developed. Fr Lazarus’s attempts to recover the largely dispersed English group were not suffered to long continue.

The Synod of the Russian Church Abroad had moved from Karlovci to Munich, fleeing from the new generation Communists. In 1949, the Synod was given hospitality by the USA, and removed its Seat to New York, where it has remained ever since. It was a sensible decision on the part of Metropolitan Anastassy to send for Fr Lazarus, a native-born English speaker, to serve with the Synod in an English-speaking country. He served as a secretary to the Synod. Whilst he was there, the Synod, in company with all other Heads of Orthodox Churches, became the recipient of a request from the so-termed ‘Catholicos’ Party of the ancient Church of St Thomas in South India for recognition as a canonically regular Orthodox Church. The sole addressee to respond was the Russian Synod which promptly formed a small Mission to be led by Fr Lazarus to go to India to meet with the Indian hierarchs and explore the possibilities of the Indian situation. He was accompanied by a small young American rassophore monk, Brother Joseph, the nun Maria (Domverg) and another Scottish (lay) woman known as ‘sister’ Mary (who wore secular clothes) who acted as secretary to the mission.[26]There are no more details about the identity of the Monk Joseph, but Sister Mary appears to be Novice Mary Pavlenko nee Schatiloff. She had known Fr Lazarus from when he was first received into the … Continue reading Fr Lazarus wanted me to join them but insuperable difficulties of a personal nature ultimately precluded my passage to India. The Mission travelled first to London where it was delayed for some time overcoming problems arising from the Indian visa requirements of the tri-national group. Because of the stop-over I was enabled to meet ‘the English Archimandrite’, and through him arrange my reception into the Orthodox Church at the podvorie at Barons Court, London. He rented a room nearby where he worked on his translations of the Liturgy and The Ladder of St John Climacus during the time of waiting, when I was privileged to make some modest contribution to the work of translation.

Fr Lazarus’s Mission in Malabar did not have a successful outcome in ecclesiastical terms, largely because the Indians would not agree to amend either their formularies or their liturgical texts in the interest of a recovery of the Church’s true Orthodoxy. None of his companions could long endure the climate. Brother Joseph was the first to go, joining the staff of an English-style ‘Public School’ in the Hills. Mother Maria, overcome by the climate, returned originally to Galilee, moving on later to care for her mother in Athens. What the final destination of Sister Mary was, I do not know.[27]It seems that Sister Mary eventually moved back to America. Fr Lazarus remained alone, moving to Utta Pradesh in 1963. The young Mark Meyrick, who would become an Archimandrite, Fr David of the brotherhood of St Seraphim at Walsingham, was sent out to Fr Lazarus in the 1960s. Fr Lazarus established an Orthodox ashram with Brother Mark, Brother Leon (the ikonographer), Sister Mary, Sister Lilya[28]Better known as Mother Gavrilla, whose time with Fr Lazarus is recounted in the biography of her- ‘Mother Gavrilla: The Ascetic of Love’ (Tertios Press: 2008) and Sister Thamais (Thomas). The property upon which the group established itself belonged to the Methodist Church. In some way they aroused the hostility of the Methodist authorities, who required all, save Fr Lazarus, to vacate the premises.

Fr. Lazarus with fut. Archim David Meyrick (center row, left) and Leon Liddament (center row, right). Gerontissa Gavrilla (front row, left). Ashram in Utta Pradesh. 1963

Fr Lazarus worked in India, on this sojourn, for some twenty years. He had come out in 1952. In 1972, feeling perhaps that his usefulness in India had come to an end,[29]In actual fact, Fr Lazarus was given two months to relocate by the police, or face imprisonment. he accepted an invitation to Greece to take charge of the Russian Church and serve the Russian Old People’s Home in Athens. There are conflicting accounts of the duration of his stay there; some say two years, others five.[30]The true dates for this period are 1972-1974. At some date, perhaps in 1974, he was invited to Australia, to help in a Greek parish.[31]In 1974, Fr Lazarus was first invited by Fr. Rostilslav Gan to serve in the crypt chapel of The Parish of the Protection of the Mother of God in Cabramatta, Australia. He also was very involved with … Continue readingArchbishop Stylianos invited him to pass under his own Omophor but it appears that the Russian Synod in America ignored Fr Lazarus’s request for canonical release to that end. The situation becomes even more obscure about this time. The rumour spread among members of the Russian Church that Fr Lazarus had been separated from the Synod in consequence of his involvement in the Charismatic Movement in Australia.[32]The relationship between Fr Lazarus and the Charismatic Movement is difficult to assess due to the lack of sources. However, we do know that by the early 1970s there were considerable suspicions … Continue reading It appears that he was welcomed under the Omophor of His Grace Bishop Gibran (Gabriel Remlaouy) of Larissa, Antiochian Exarch for Australia and New Zealand, who had his Seat in Sydney. Fr Lazarus remained in Australia for nine years, serving during the later years there with a Lebanese priest at St Nicholas’s Church, Melbourne.[33]Upon being received into the Antiochian Orthodox Church, Fr Lazarus initially went to live at an ecumenical community called the ‘Beth Shalom Community’ in Hobart. However, for health … Continue reading

In 1983, Fr Lazarus responded to an invitation from Fr Peter Gillquist, a principal leader of the extraordinary Campus Crusade Movement, which developed into the EOC (Evangelical Orthodox Church).[34]Fr Lazarus first travelled to America in 1982. There he met the EOC, and was invited to return and help guide them to Orthodoxy. Under the auspices of Fr Angelo Pepps,[35]A student at Holy Cross, Greek Orthodox School of Theology. the Archimandrite left Melbourne for California and the dynamic movement born on the campus of Berkeley University. It was reported that he was invited to head their newly-established theological seminary and played some part in bringing in a substantial number of those involved into the metropolia of Metropolitan Philip (Saliba) of New York. His association with the Charismatic Movement caused some personalities in the EOC to view him with some caution. He lived for six years in Isla Vista, California, in the home of Jan Isham. During that time he visited several EOC centres, including one in Eagle River, Alaska. In December 1989, at the request of the parish, he moved into the home of Deacon Harley and Dianne (Dominica) Cranor, remaining with them until his final repose on 27th November 1992.

In the summer of 1992, Fr Lazarus was reported to have been reconciled with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia,[36]This is confirmed. In 1992, Metropolitan Hilarion asked Hieromonk Benedict (Greene) to hear Fr Lazarus’ confession and receive him back into the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. but his obsequies were celebrated in the Antiochian Cathedral Church of St John, Eagle River, in whose burial ground his remains were interred. Although his Orthodox formation was indisputably Russian in the ‘pure’ tradition, he was never ‘ethnically’ limited. As his record of world service demonstrates, he was a truly oecumenical Orthodox Christian who served the Church of Christ across the continents.

Father Lazarus grave in Eagle River, AKSpiritual Fathers, but never claimed to be or sought recognition as an academic scholar. He was a Man in Christ Jesus.

He was equally at home with Russians, Greeks, Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians, Englishmen, Australians and Americans (including, no doubt, Aleuts). But whilst absolutely deep-dyed in Orthodoxy, he remained a representative of the best kind of Christian English gentleman to his dying day. He had command of several languages and was a master of the spiritual life. He was an authority in the living Tradition of the

His spiritual children are to be found in many countries and several continents. We all greatly loved him and cherish our own particular personal memories of him and of incidents shared with him. We send our love to his surviving relatives and commend them and him to the all-embracing love of our Risen Lord, in the Glory of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, to Whom be Glory in the Church, now and unto the Ages of Ages. Amen.

Appendix

A Letter from Fr Lazarus (Moore) to the Very Revd. Cosmo Lang, Archbishop of Canterbury[37]This letter is located in the Lang Papers, pp. 64-66.

Russian Mission, Jerusalem.

1 Feb. 1936

Your Grace,

I became a priest and monk of the Holy Orthodox Church entirely of my own free will, wholly in obedience to what I believe to be the will of God for me. As it was in India that the call came to me, far indeed away from any human Orthodox contact, it is sufficiently evident, I believe, that mine was not a case of any human conversion. In fact, I stayed about another year in India before coming to Europe, and my reception into Orthodoxy. And I left the diocese of Bombay with the blessing of the bishop and my Confessor-Director.

I have found that this exterior obedience has corresponded with my interior life. For I find that wherever Anglicanism differs from Orthodoxy, (in all important matters) I share the Orthodox view, and I must admit that as an Anglican I found myself so much at variance with Anglicanism that mine was becoming rather a questioning spirit than a spiritual quest, and one is a poor advocate of what one does not believe in and support with all one’s heart.

For example in an Oecumenical Council it was agreed that the Creed (Symbol), should never be altered except by Oecumenical consent. In the West, this pact was broken, and an important clause inserted locally and irregularly. Were there no other reason, the penitence and reparation would be obviously due from the Anglican to the Orthodox Church in all relations for reunion. But one finds an attitude of equality, even sometimes of superiority.

Anglicanism glories in its comprehensiveness, but to me it is an offence and stumbling block. I found that in South India, doctrines are preached which are the exact reverse of what I was preaching. What that has meant to the Church of Malabar founded by St Thomas cannot be estimated; briefly to them Anglicanism means C.M.S. or, in other words, Protestantism. And the recent joint services of Holy Communion at which Anglicans and Non-conformists partake of the Sacraments together in the diocese of Travancore has increased the bewilderment.

I have come to believe that the True Church is Holy Orthodoxy, for she alone receives, recites and keeps the Faith, as regularised by the Councils, intact and word-perfect. The extent of the loss of Holy Tradition in the Church of England after the so-called Reformation can be gauged to some extent by the fact that what Our Lord, Jesus Christ, and His Apostles call ‘works of the devil’ (i.e. sickness) came to be called in the Book of Common Prayer ‘the visitation of God’. And instead of obeying the command to ‘heal the sick’ by the Sacrament of Anointing, exorcism, etc, as has always been the case in Orthodoxy (Orthodox prayers are unqualified appeals for healing) one finds the Anglican ministry armed with the Prayer Book Office of the Visitation of the Sick. Your Grace, it is no wonder Our Saviour wept over Jerusalem.

Finally, although there is no dogma on the Church, it seems to me that the most popular doctrine (Anglican) is the ‘branch theory’ viz. that the R.C., Orthodox and Anglican bodies are three branches of a single vine, which have got separated, although they fundamentally are one. If that is so, I have not left the Church. However, I believe that to be a Protestant theory, for it means that the unity of the Church is only invisible, and that the Gates of Hell have prevailed against the visible unity of the Church. For I believe that the Church, like her Head, is a Divine-Human organism and that the fullness of the Church is Holy Orthodoxy and she is the True Bride of Christ. Can I be blamed, Your Grace, with such a belief, from following her wherever she calls me?

Truly woeful is it when all men speak well of you, and we rejoice that we are spoken evil of and reviled for God’s sake, and our love only increases. But while we pray for our enemies, of your love we beg Your Grace for Truth’s sake to silence those of your flock who spread bad reports, for they are the real enemies of the union of the Church. My love for the Anglican Church does not diminish. My daily prayer is that we may all be one. I am a frequent advocate of what is true in Anglicanism, and I pray that I may never think or speak ill of her.

I ask Your Grace’s forgiveness and prayers, and remain,

Yours humbly in the Divine Service,

Hieromonk Lazarus (formerly Edgar Moore)

Abbreviations

Canterbury Papers – Ref. CCA-U88/ A/ 2/ 6/ C/715 File of Letters originally held by St Augustine’s College Canterbury, now in the Archive of Canterbury Cathedral.

Douglas Papers – Ref. Douglas Papers Volume 46, ff. 296-396 passim Correspondence concerning Fr Lazarus Moore held by Canon J A Douglas regarding Fr Lazarus in Lambeth Palace Archives.

Lang Papers – Ref. Lang 145, ff. 56-98 Correspondence concerning Fr Lazarus Moore held by the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Lang in Lambeth Palace Archives.

Garth Moore Papers – Ref. 4972 – 4980 – Evelyn Garth Moore papers / MS 4974 Correspondence between Fr Lazarus Moore and his cousin Evelyn Garth Moore held at Lambeth Palace Archives.

References

| ↵1 | A further reference in the Garth Moore correspondence confirms without doubt that Fr Lazarus was the author. With characteristic humility he writes on Easter Day 1957, ‘I translated & compiled a more or less full length Life of S. Seraphim in Palestine, & I translated a shorter Life. The former is not likely to get beyond MS stage as it is no doubt without literary merit, but the latter has been printed in a journal in USA & I cd send you a copy if you cared to see it.’ (Garth Moore Papers, p. 45) |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | We are informed by Dominica Cranor that, in actual fact, the initial diagnosis was of prostate cancer, which was later found to have spread to the lungs and bones. |

| ↵3 | His father was a stockbroker on the London Stock Exchange. |

| ↵4 | Fr Lazarus’ five siblings are: Geoffrey Moore, Norman Moore, Martin Cedric Moore, Charles Roger Moore and Lorna Matheson. Whilst Charles and Martin were in the armed forces during WWII it has not been possible to identify who the Vice Admiral was, if Fr Andrew got that detail correct. |

| ↵5 | He began his education at Elstree Preparatory School between 1907-1916 and then moved up to Aldenham School between 1916-1919. |

| ↵6 | Edgar was enrolled at the College from 1926-1930. |

| ↵7 | The inconsistencies in the chronology are resolved in an “Oral History Paper” completed for a Sociology Class on 11 March 1986 by Stephanie Rae who interviewed Fr Lazarus about his life. Apparently, due to financial reasons, Edgar had to be withdrawn from his fee-paying public school at the age of 16. Although offered the opportunity of military service, Edgar declined this in favour of learning to become a farmer. Thus he enrolled at Reading Agricultural College for two years, between 1919-1921. Upon completion of his studies, it was then arranged that he should stay with an Uncle in Canada and work as a ‘chore-boy on a senator’s farm.’ The Senator was Hewitt Bostock whose farm was at Monte Creek in Kamloops (Camloops), British Columbia. |

| ↵8 | According to a recent survey, this number now stands at approximately 2,100,000. |

| ↵9 | The ‘Bombay Liturgy’ is similar to the Orthodox Liturgies of Sts Basil the Great and John Chrysostom in several respects through the insertion of the Trisagion, litanies pronounced by the deacon, a litany for and dismissal of the catechumens, the epiklesis and, from the rubrics, a clear understanding that this completed the consecration of the Holy Gifts. |

| ↵10 | Fr Edgar arrived at the Ashram on 10 June, 1933. He remained there almost exactly a year, leaving in June of the following year. |

| ↵11 | Actually, Fr Edgar had made contact with the ‘Syrian Orthodox Church’, through accepting invitations to lead retreats in Travancore in January 1934. (cf. Letter from Edgar Moore to the Warden of St Augustine’s College: Canon J.W.S. Tomlin dated 8 February 1934 (Canterbury Papers, Document Ref. A2/6 C715/47 (1 – 3)). |

| ↵12 | Archbishop Anastassy advised Fr Edgar to seek out and live with the nearest Orthodox priest. He stayed with Fr Andronik from October 1934 to May 1935. Fr Andronik later went on to become the rector of St Tikhon’s Seminary in Pennsylvania. |

| ↵13 | The College is still open at the time of writing in 2014, and must therefore be nearly approaching its 200th Anniversary. |

| ↵14 | It is still a mystery as to which book by Zernov could have so inspired Fr Lazarus. |

| ↵15 | Either a Russian or at least canonically Orthodox Bishop. |

| ↵16 | There are now approximately 7,000 Anglicans served by the Diocese of Jerusalem. |

| ↵17 | There are now approximately 55,000 Melkite Catholics in Palestine. |

| ↵18 | We now know this visit took place in 1935. Father Lazarus stayed at the Holy Monastery of St Panteleimon on Mount Athos with Fr Winslow. This is detailed in a letter dated December 1935 from the Bishop of Gibraltar who was visiting Mount Athos at the same time. He records – ‘I spent only a few hours at Panteleimon (the Russian Monastery). To my surprise I found there an Anglican Priest, Moore from S. India – formerly member of Christa Seva Sang (sic) with Fr Winslow. Moore is under instruction to become Orthodox he told me.’ (Douglas Papers, p. 297) |

| ↵19 | Fr Lazarus told Dominica Cranor that Archbishop Theophan made him a deacon, and then a priest one week later, on 28 December at Milkovo Monastery in Yugoslavia. |

| ↵20 | It would seem, at least from the archival record, that the ordination of Father Lazarus did not carry the explicit blessing of the Serbian Patriarch Varnava. This is stated in a letter from Irenei, Bishop of Novi Sad to Canon Douglas on 16 January, 1936. ‘Our Patriarch refused to receive Rev. Moore, and was not willing to reordain him. He recommended also the Russian Bishops refuse reordination.’ (Douglas Papers, p. 26) St Nikolai (Velimirovic) also states in a letter to Canon Douglas on 16 January, ‘Rev. E Moore produced no papers whatsoever about his status and in great hurry he asked us at once three things to do for him; ie. to receive him into the Orthodox Church, to reordain him and to send him back to the East [for] Missionary work. On those grounds our Patriarch refused to do anything in this matter.’ (Douglas Papers, p. 28) |

| ↵21 | c.f. “The Case of Father Lazarus Moore” in the Glastonbury Bulletin No. 65, November 1982, p.143 et seq. |

| ↵22 | Technically Fr Lazarus laboured in the Holy Land for 13 years, from 1935-1948. He then worked for a further year from 1948-1949 in the Transjordan. |

| ↵23 | St John was officially glorified in 1994 by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. |

| ↵24 | In 2008, the Israeli Government returned a 9-acre plot – Sergei’s Courtyard, named after the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich – to Russia. |

| ↵25 | The details of this are recorded in Fr Lazarus’ correspondence from the Holy Land with his cousin, Evelyn Garth Moore (Garth Moore Papers). |

| ↵26 | There are no more details about the identity of the Monk Joseph, but Sister Mary appears to be Novice

Mary Pavlenko nee Schatiloff. She had known Fr Lazarus from when he was first received into the Orthodox Church in Serbia. |

| ↵27 | It seems that Sister Mary eventually moved back to America. |

| ↵28 | Better known as Mother Gavrilla, whose time with Fr Lazarus is recounted in the biography of her- ‘Mother Gavrilla: The Ascetic of Love’ (Tertios Press: 2008) |

| ↵29 | In actual fact, Fr Lazarus was given two months to relocate by the police, or face imprisonment. |

| ↵30 | The true dates for this period are 1972-1974. |

| ↵31 | In 1974, Fr Lazarus was first invited by Fr. Rostilslav Gan to serve in the crypt chapel of The Parish of the Protection of the Mother of God in Cabramatta, Australia. He also was very involved with the Greek Orthodox Church, leading bible study groups. |

| ↵32 | The relationship between Fr Lazarus and the Charismatic Movement is difficult to assess due to the lack of sources. However, we do know that by the early 1970s there were considerable suspicions about the depth of his involvement in the Pentecostal, Charismatic Movement. This led to an investigation by Archbishop Theodosy and the eventual decree by the Synod of Bishops on 18 November 1975, that Fr Lazarus should be defrocked and suspended from his priestly duties (Decree No.11 /35/900). |

| ↵33 | Upon being received into the Antiochian Orthodox Church, Fr Lazarus initially went to live at an ecumenical community called the ‘Beth Shalom Community’ in Hobart. However, for health reasons, Fr Lazarus then returned to Melbourne and served at St Nicholas Church until 1983. |

| ↵34 | Fr Lazarus first travelled to America in 1982. There he met the EOC, and was invited to return and help guide them to Orthodoxy. |

| ↵35 | A student at Holy Cross, Greek Orthodox School of Theology. |

| ↵36 | This is confirmed. In 1992, Metropolitan Hilarion asked Hieromonk Benedict (Greene) to hear Fr Lazarus’ confession and receive him back into the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. |

| ↵37 | This letter is located in the Lang Papers, pp. 64-66. |

Archimandrite Lazarus labored at a time when little Orthodox material was available in English, particularly in the pre Internet era. His superb writings and translations are easily read, enjoyable, and completely faithful to the original languages. As a master par excellence, his liturgical translations soar above all others! They are truly poetic and in a unique style that I have seen no other translator ever write.

This article fails to mention that while in New York in the 1950’s, Fr. Lazarus worked directly with Archbishop James (Toombs) of ROCOR’s American Mission, later The American Orthodox Church. A significant corpus of liturgical translations was produced in this era and in this collaboration.

In another article here on ROCOR Studies by Michael Woerl, “Archbishop James (Toombs, d. November 1970) of Manhattan, Head of the American Orthodox Mission, Vicar of the Diocese of Eastern America and Jersey City,” there is just a simple one sentence mention – “Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore, 1902 – 1992) helped with translations.” Just as Mr. Woerl’s simple mention, were it not for Dominica Cranor, and the living usage of the OAC, Fr. Lazarus might have passed into obscurity.

ETERNAL MEMORY!

A great adventure in Orthodox Mission To the East and all of The Globe.Aby@Mount of Saint Thomas Chennai

[…] Fr. Andrew Midgley, “A Lifetime in Pilgrimage”, Mettingham, Suffolk, 2014, http://www.rocorstudies.org/2017/02/11/a-lifetime-in-pilgrimage-archimandrite-lazarus-moore-1902-199…, last accessed August 1st, […]

Can I get something more about Fr Andronik especially his eighteen years in India