When, in 1995, I began teaching Russian Church History at Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville I found myself faced with the lack of a suitable textbook. Ivan Mikhailovich Andreev’s work Kratkii obzor istorii russkoi tserkvi ot revoliutsii do nashikh dnei [A Brief History of the Russian Church from the Revolution to the Present Day] was indeed brief (at 180 pages) and was unable to account for the new historical information that had become available in the 1990s. Thus, in summer 1999, a new, bulky, 480-page-long “reader,” comparable with the learning materials used in colleges, was prepared for the students. The article below is a chapter from this book. This text is still readable 20 years later, which cannot be said of all of my articles published in Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia]. In addition, I would mention, in the section on Metropolitan Sergius’ first term, the friendly letter he sent to the ROCOR hierarchs in 1926, which was indiscreetly published abroad. Metropolitan Sergius’ circumstances during his second period of imprisonment have still not been clarified, and the materials from his case file from early 1927 up to his release in spring of the same year are still not available to researchers. The article is being published as is, without any edits; hence the insufficient citing of sources without page numbers and use of the indecorous turn of phrases like “servants of the Moscow Patriarchate”. This translation has been made possible by a grant from the American Russian Aid Association – Otrada, Inc.

Sep. 26, 2019, Chicago

Years Leading up to the Bolshevik Regime

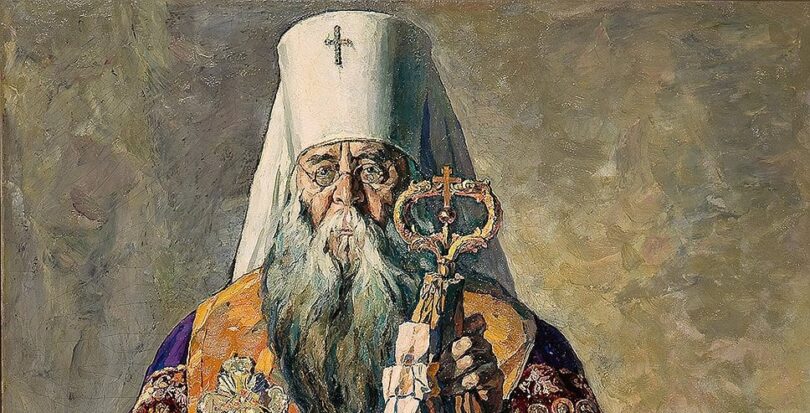

Metropolitan Sergius was one of the foremost figures in the life of the Russian Church. He was born in Arzamas in 1867. He came from an old clergy family and excelled in his studies at various theological institutes. He had a burning, living faith that led him on to spiritual feats. Archimandrite Sergius twice visited Japan as a missionary, and on the second occasion he was accompanied by the future hieromartyr Andronicus (Nikol’skii), Archbishop of Perm. Archimandrite Sergius learned Japanese to such a high level that he was able to teach dogmatic theology in the language at the local seminary. Just like his teacher, Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitskii), Metropolitan Sergius sought to make Orthodox dogmatics something living that could be experienced by the Christian soul, rather than it being a mere theological and philosophical system detached from life. In this context, Archimandrite Sergius’ book Pravoslavnoe uchenie o spasenii [The Orthodox Teaching on Salvation] (his candidate of theology dissertation) is an outstanding work, in which the author demonstrates his profound knowledge and understanding of the works of the Holy Fathers. Despite the fact that Metropolitan Sergius’ views were not entirely free from the spirit of the times – he took a positive stance on second marriages for priests – the general impression that one gets of Metropolitan Sergius is that of a man for whom Orthodoxy is dear “as truth and life, with all its dogmas and traditions, with its entire canonical and liturgical framework”. The following words, spoken by Metropolitan Sergius at a moleben in the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy on February 17, 1905, are worthy of note. Metropolitan Sergius was giving a speech about a time when the laws of the country would cease to be a bulwark and defense for the Russian Church. “Then,” he predicted, “what will be required of us will not be eloquent turns of phrase or learned syllogisms, but spirit and life; faith and fervent loyalty and perfusion with the Spirit will be required of us; we will be required to write not with inks, even ones borrowed from others’ ink-pots, but with the blood from our own breasts… Will we respond to these demands, will we bear this trial by fire, will we stand at this truly dread judgment? For we will be judged not by our good-natured hierarchy, nor by ourselves, but rather by the Church of God Herself, by the Orthodox people who have entrusted us with the affairs of the Church and who will have no regrets about turning their backs on us and casting us out if they find in us ‘whitewashed tombs’ and ‘salt that has lost its savor’.”

The young Bishop Sergius demonstrated himself to be an excellent missionary among the “god-seeking” intelligentsia during his time chairing the courses of the Religious and Philosophical Society. Bishop Sergius’ conservatism can be seen in his reply to Merezhkovsky’s assertion that the Church rejects the theater: “The theater is a form of service not only to the sublime, but also […] to the crude and sensual. If church figures were to go to the theater, in doing so they would sanctify this service to sensuality… The principle here is clear. The struggle waged in life is not so much between the flesh and the spirit as between heavenly and earthly ideals. Christianity presents mankind with the heavenly ideal […] and everything that is conductive to attaining this ideal is blessed by it. Everything that works against attaining it is rejected… Christianity does not put what is earthly first […] because mankind must [itself] strive to attain earthly ideals.” I find the following rather accurate comment by Zinaida Gippius, one of the leaders of the Society from the non-Church party of the intelligentsia, to be worthy of note: she called Bishop Sergius a quasi-Buddhist.

Bishop Sergius, like many others at the time, held the Czar responsible for the shooting of the procession on January 9, 1905 (Bloody Sunday). The Imperial family, in turn, was not well disposed toward him. One of the far-right Russian patriots of the time, Alexander Dubrovin, wrote to Metropolitan Antony (Vadkovskii), whose vicar Bishop Sergius was: “The patriots have been persecuted, but Antonin is still there, as is Sergius, who served a blasphemous panikhida to the insurrectionist Schmidt on behalf of the rebels [Schmidt was executed in 1906; he led the uprising on the cruiser Ochakov, was a member of the Sebastopol Revolutionary Committee, and gave the orders to bombard the Black Sea ports —A.P.], and you protected him even when a theft of money was discovered to have taken place in the Academy and he was at fault.”

It should be noted that, after years of living close to the capital of the Russian Empire, Bishop Sergius became an experienced and pragmatic politician, well-tempered by the vicissitudes of job-swapping at the Synod.

It was thanks to Bishop Sergius that the grand duchesses met Grigory Rasputin and introduced the latter to the Imperial family.

Fr. George Gapon, the well-known workers’ leader, was also a protégé of Bishop Sergius; he was connected with both the revolutionaries and the secret police. Sergius even thought that, when Gapon became a widower, he might be made bishop. In his book Krushenie imperii [Downfall of an Empire], Mikhail Rodzianko wrote that when Oberprokuror Sabler proposed elevating Archimandrite Barnabas, a protégé of Rasputin’s, to the rank of bishop, this proposal was unanimously rejected by the Synod under Metropolitan Antony Vadkovskii. However, when the latter fell ill and Archbishop Sergius assumed the presidency of the Synod, the matter was resolved affirmatively by a majority of the members of the Synod.

When the 1917 revolution came about, Metropolitan Sergius emerged as a staunch backer of the separation of church and state, for he deemed the state to have suppressed and restricted the Church in czarist Russia. Metropolitan Sergius was the only member of the old Synod whom the Provisional Government admitted to the Synod it had established. In a diary entry from May 30, 1917, Fr. Nikolai Liubimov, Protopresbyter of the Holy Dormition Cathedral in Moscow, gave a characterization of Metropolitan Sergius that is worthy of our attention. At this time, the question had arisen as to whether the current Synod could be dissolved and a new one established in its place. “Only Archbishop Sergius alone, wanting, as ever, both to acquire capital and preserve his innocence at the same time, started talking some nonsense, saying that he completely understood and appreciated the Oberprokuror’s wishes, that it was indecent of us to argue in favor of the current make-up of the Synod, since we belong to it ourselves and this would mean protecting our own rights. ‘Ah!’ I thought upon hearing the Archbishop’s words, ‘what a clever fellow you are! You alone, out of everybody, managed to stay in the Synod after it was broken up the last time, and when it is broken up this time, you will again remain a member of the next one. Now that’s how you adapt to changing circumstances! Honor and praise be to you, you cunning archpastor!’”[1]Dnevnik o zasedaniiakh vnov’ sformirovannogo sinoda 12 aprelia — 12 iiunia, 1917 g. [Diary on the Sessions of the Newly Formed Synod of April 12-June 12, 1917]. Moscow: Patriarchal Metochion … Continue reading.

Under the Bolsheviks, Metropolitan Sergius was released from prison thanks to Vladimir Putyata, former Archbishop of Penza, who had developed a rapport with the Bolsheviks. The latter was deposed and excommunicated for his monstrous deeds by the Council of 1917-18. Shortly thereafter, Metropolitan Sergius wrote a lengthy report defending the depraved Putyata and emerged as Putyata’s advocate with the Patriarch, the Holy Synod, and the Church Council concerning his restoration to the episcopate.

The Troubled Years: 1922-1925

In May 1922, His Holiness the Patriarch was arrested and his chancellery seized by the Renovationists. Metropolitan Agathangel, Patriarchal locum tenens, was temporary administrator at the time. It seemed that chaos was engulfing the church. On May 29/June 10, 1922, the trial of Metropolitan Benjamin of Petrograd began. (The Metropolitan had been elected to his see by the entirety of the flock of the diocese.) The trial ended with issuance of a death sentence for the Metropolitan. Several days before being executed, Metropolitan Benjamin wrote a letter to one of the St. Petersburg deans. “In my childhood and adolescence,” he wrote, “I would read and become absorbed in the lives of the saints, and was filled with admiration their heroism, their holy inspiration, and regretted with all my heart that our time was different and we no longer had to live through the things that they did. But times have changed again, and we now have the opportunity to suffer for Christ’s sake at the hands of both our own people and others. It is hard, difficult to suffer, but consolation from God abounds according to the measure of our sufferings. It is difficult to cross that Rubicon and surrender oneself entirely to the will of God. When this is accomplished, a person abounds in comfort and does not feel even the most dire sufferings, as he is full of inner peace, and he leads others on to suffering so that they might themselves experience the state of the happy sufferer […] I am as joyful and peaceful as always. Christ is our life, light, and peace. With Him, you are always well, everywhere. I do not fear for the fate of the Church of God. We pastors have to have more faith. We have to forget about our self-reliance, our mind, learnedness, and strength, and give way to the Grace of God. I find the musings of some perhaps outstanding pastors — by which I mean Platonov — to be strange. They say we need to sustain our vital forces, that is, to forgo everything for the sake of these forces. But then what is Christ good for? It is not Platonov, nor Chepurin, nor Benjamin, nor their like who save the Church; but it is Christ. The position they are attempting to adopt is ruinous for the Church. [my emphasis —A.P]. We must not spare ourselves for the sake of the Church, rather than sacrificing the Church for our own sake.” Metropolitan Benjamin was executed by firing squad along with three other martyrs. In these last words of his, he sets out the path of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia.

At the height of the trial in Petrograd, the so-called “Memorandum of the Three” appeared in the Renovationist publication Zhivaia tserkov’ [Living Church] (June 16, 1922). In it, three venerable hierarchs – Metropolitan Sergius (Stargorodskii) of Vladimir, and Archbishops Evdokim (Meshcherskii) of Nizhny Novgorod and Seraphim (Meshcheriakov) of Kostroma – acknowledged the self-proclaimed Renovationist Supreme Church Governance to be “the sole canonical authority in the church”. Metropolitan Sergius probably thought that the Patriarch had been arrested and it was uncertain whether he would ever be released. In joining the Renovationists, he was hoping to exert a positive influence on them, or, at the very least, to preserve his Diocese of Vladimir, which might fall under the authority of the present Renovationist bishop.

Nearly half of the Russian episcopate followed the example of these eminent bishops. Some of them were completely at a loss for what to do, others were inflamed with ambition, and others still were hoping to steer the Renovationist movement back to the mainstream of canonicity and head up the Supreme Church Governance. In the words of Metropolitan Manuil, the thinking of many bishops and clergymen at the time was: “If Sergius, in all his wisdom, has acknowledged the possibility of submitting to the Supreme Church Governance, it is clear that we ought to follow his example.” After Patriarch Tikhon’s release, Metropolitan Sergius was received by him through repentance into communion with the Orthodox Church.

In the early 1920s, the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) was basically held captive by the Soviet regime. The ROC was the only active institution in the USSR that was left from the Old Russia of the past millennium. However, the ROC did not have any legal status in the USSR until after the end of Patriarch Tikhon’s life, which meant that the activities of its millions of members could at any moment be deemed punishable by law. In the hope of remedying this situation, Patriarch Tikhon was in constant contact with representatives of the Soviet regime. The latter attempted to get their own way with him without giving him anything in return. Patriarch Tikhon was the primate of the Russian Church, having been elected by the entirety of the people of the Church. His authority was enormous and incontrovertible. Therefore, the love of the people covered over even such acts of his as the introduction of the Gregorian calendar or his public repentance before the Bolsheviks. The patriarch himself was united spiritually with the leading bishops of the Russian Church, such as Metropolitan Kyrill (Smirnov) and Archbishop Feodor (Pozdeevskii, who was an “Abba” to many bishops), who in turn gave voice to the stance of the overwhelming majority of the Tikhonite episcopate. For instance, it was due to Metropolitan Kyrill’s insistence that the Patriarch refused to ally himself with the Renovationists. In this way, Patriarch Tikhon upheld one of the fundamental church canons: the 34th Apostolic Canon, which states that a First Hierarch should not do anything without consulting other bishops.

In his well-known statements supporting the Soviet regime, the Patriarch was speaking for himself and not on behalf of the whole Church. He did not force this position of his upon anyone else, as one can see from the fact that, when the faithful ignored the decree that he sent around concerning commemoration of the regime, His Holiness did not enforce it. His Holiness did not impose any sanctions on those who disagreed with his position, such as Archbishop Feodor of Volokalamsk, or on those who adhered to the resolutions of the 1917 council concerning regimes hostile to the Church (for example, the council adopted the Patriarch’s anathema against the enemies of God and on April 6, 1918 issued a ban on appealing with respect to church affairs to a regime that was hostile towards the Church), although he may have been discontent with their actions – for instance, with respect to the Synod of Bishops of the Church Abroad. To be brief, Patriarch Tikhon did not introduce anything new into the internal life of the Church, of which he remained a true guardian.

According to Patriarch Tikhon’s testament (whose composition can be put down to the will of the Council of 1917-18 and the extraordinary external circumstances of the life of the Church), the following, in order of precedence, where to become Patriarchal locum tenentes in the event of his death: Metropolitan Kyrill of Kazan, Metropolitan Agathangel (Preobrazhenskii) of Yaroslavl, and Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy. Since the first two could not take up their duties, Metropolitan Peter (Polianskii) of Krutitsy assumed the powers of Patriarchal locum tenens. His election was confirmed by the signatures of the 58 bishops who gathered together for Patriarch Tikhon’s funeral in April 1925.

Metropolitan Peter steered the Church along the course set by Patriarch Tikhon. He also sought to have the Church legitimized. Immediately after Metropolitan Peter became head of the Russian Church, he gave an interview to the Izvestia newspaper. Asked the question, “When do you intend to carry out a purge of counter-revolutionary clergy and black-hundredist parishes, and to convene a Commission to put the émigré bishops on trial?”, the Metropolitan replied: “For me, as locum tenens of the Patriarchal Throne, the Patriarch’s will is sacred, and I alone do not have the right to enact all these points of his testament” (my emphasis —A.P.).

“In autumn 1925, the locum tenens (…) resolved to compose and submit his Declaration to the Soviet government and show how he viewed the relationship between the ROC and the Soviet government. Metropolitan Peter sketched out an initial version and certain points of a draft of this declaration and sent it to Bishop Joasaph (Udalov) Chistopol’skii, asking him to turn it into a full-fledged text. Bishop Joasaph composed a draft of the text, read it out to several bishops living at the time in Danilov Monastery – Bishops Pachomy (Kedrov) Chernigovskii, Parfeny (Brianskikh) Anan’evskii, and Amvrosy (Polyanskikh) of Kaments Podol’sk – and, having taken their comments into account, incorporated their corrections into the text and passed it on to the locum tenens.[2], Hieromonk Damaskin (Orlovskii),. Mucheniki, ispovedniki i podvizhniki blagochestiia Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi XX stoletiia [Martyrs, Confessors, and Strugglers for Piety in the Russian Orthodox … Continue reading These bishops whom Metropolitan Peter consulted were of the same school of thought as Archbishop Feodor (Pozdeevskii).

Metropolitan Peter’s declaration did not say anything new relative to what Patriarch Tikhon had said, and was thus rejected by the regime. Seeing that they could not make Metropolitan Peter an obedient collaborator, the Soviet authorities arrested him. It was then that Metropolitan Peter’s instruction came into effect: “In the event that, owing to whatever circumstances, I am unable to carry out the duties of Patriarchal locum tenens, I temporarily entrust the performance of these duties to His Eminence Sergius (Stargorodskii), Metropolitan of Nizhny Novgorod. Should this metropolitan does not have the ability to carry this out, then His Eminence Mikhail (Ermakov), Exarch in the Ukraine, shall temporarily assume the duties of Patriarchal locum tenens; or else His Eminence Joseph (Petrovykh), Archbishop of Rostov, should Metropolitan Mikhail (Ermakov) be unable to carry out my instruction. I am still to be commemorated at services as Patriarchal locum tenens.” Thus, unlike those of Patriarch Tikhon and his appointee Metropolitan Peter, Metropolitan Sergius’ powers derived not from the conciliar will of the episcopate, but rather merely from the powers of the Patriarchal locum tenens, Metropolitan Peter, whose deputy he was. This unprecedented step of a locum tenens appointing a deputy for himself was accepted by the episcopate of the Russian Church out of respect for Metropolitan Peter and for the sake of preserving the unity of the Russian Church.

First Term as Deputy to the Locum Tenens (1925-1926)

Metropolitan Sergius’ understanding of his ecclesiastical powers and his tactics for defending them were demonstrated very clearly in his interactions with Metropolitan Agathangel. When the latter was freed from imprisonment after four years, he issued the encyclical “To the Archpastors, Pastors, and All the Children of the Russian Church” in Perm on April 18, 1926. In it, he announced that he was assuming governance of the Church on the following basis:

- a) the resolutions of the Local Council of the ROC of 1917-18;

- b) Patriarch Tikhon’s letter of May 3/16, 1922;

- c) his encyclical of June 2/15, 1923;

- d) and the instruction of the same on the occasion of his death, from December 25, 1924/January 7, 1925.

The GPU (Soviet secret police –A.P.) had clearly been hoping that Metropolitan Agathangel’s release would cause a new division in the Church, which at the time had been successfully resisting the new Gregorianist schism. Metropolitans Sergius and Agathangel met in Moscow on May 13. Metropolitan Sergius agreed to transfer authority to Metropolitan Agathangel. However, after returning to Nizhny Novgorod, he wrote to him saying that he had misunderstood the Local Council’s resolution about the locum tenens, and that he (Metropolitan Sergius) therefore could therefore not transfer authority to him, even though, as he wrote, “should Metropolitan Peter for whatever reason abandon his position of locum tenens, our eyes will, of course, turn to the candidates indicated in [Patriarch Tikhon’s] testament, that is, to Metropolitan Kyrill and then to Your Eminence.” And yet Metropolitan Peter wrote to Metropolitan Agathangel in his letter of May 22, 1926: “It is with love and good will that I welcome your assumption [of the powers of Patriarchal locum tenens —A.P.]. After I am released, God-willing, we will speak in person about the future leadership of the Orthodox Church.”

Metropolitan Sergius’ harsh approach to defending his church policy and his “flexible logic” are clearly demonstrated in his interactions with Metropolitan Agathangel. In his letter of May 24 of the same year to the administrator of the Diocese of Moscow, he said he regarded Metropolitan Agathangel as liable to an ecclesiastical trial. The book Za Khrista postradavshie: goneniia na Russkuiu Pravoslavnuiu Tserkov, 1917-1956 [“Those Who Suffered for Christ’s Sake: The Persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church from 1917-1956”] tells of how things subsequently developed: “Metropolitan Agathangel again summoned Metropolitan Sergius to come to Moscow in order that he might gather together the bishops and take over Metropolitan Sergius’ powers, but Metropolitan Sergius did not come, citing an exit ban as the reason, even though he had come to Moscow two weeks before receiving the letter”.[3]Za Khrista postradavshie: goneniia na Russkuiu Pravoslavnuiu Tserkov’ 1917-1956 gg. [Those Who Suffered for Christ’s Sake: The Persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church from 1917-1956]. … Continue reading On June 13, 1926, Metropolitan Sergius wrote a letter to Metropolitan Agathangel, in which the kind of relationship to his kyr-hierarch[4]His immediate superior. that would subsequently determine the behavior of the deputy Patiarchal locum tenens clearly comes through: “Metropolitan Peter has, albeit temporarily, handed over to me the full rights and duties of locum tenens, and since he lacks the ability to be sufficiently informed about the state of the affairs of the church, he is not able to become involved in them as an administrator. On the other hand, I […] cannot view Metropolitan Peter’s instructions issued from prison as anything other than instructions or, rather, pieces of advice by an irresponsible person.” “But Metropolitan Agathangel,” the above-mentioned book states, “according to his spiritual disposition, did not want to and could not become engaged in a struggle that would endanger the peace of the church. He had not even received the last letter [of June 13, 1926 —A.P.] from Metropolitan Sergius when he informed Metropolitan Peter (Polianskii) on June 12, 1926 that, ‘for reasons of old age and extremely fragile health’, he could not assume the duties of locum tenens.” Only after Metropolitan Agathangel sent this letter did he receive another one from Metropolitan Peter, dated June 9, in which the latter wrote: “In the event that Your Eminence should refuse or be unable to take up the duties of Patriarchal locum tenens, the rights and duties associated with this position are restored to myself, and the status of deputy to Metropolitan Sergius.” Thus, this episode involving Metropolitan Agathangel ended with Metropolitan Sergius remaining in charge of the affairs of the Church. He was supported in this capacity by other bishops, who saw an unexpected shift in the leadership of the Church as potentially endangering it, due to, among other things, the fact that the GPU might use it to engender divisions in the Church.

Thus, if one does not take into account the peculiarities of Metropolitan Sergius’ relationship with his kyr-hierarch, Metropolitan Peter, it could be said that in the first period of his leadership, from December 1925 until late 1926, he was acting in accordance with Patriarch Tikhon’s previous course of action and with the will of the episcopate (both free and captive), while even showing greater condescension to the Russian bishops abroad that the Patriarch himself had. The fact that Metropolitan Sergius gave expression to the conciliar will of the Russian Church at this time, can be seen from the incident when he suspended a group of bishops, the so-called Gregorianists, who had set up a Temporary Supreme Church Council without the blessing of Metropolitan Peter. In this action, as in his interactions with Metropolitan Agathangel, Metropolitan Sergius was supported by the entirety of the episcopate. It is important to note that Metropolitan Sergius understood the nature of his powers as deputy to be connected with those of Metropolitan Peter as Patriarchal locum tenens. This can be seen from Metropolitan Sergius’ letter of May 13/26, 1926, to Metroplitan Agathangel, in which he specified that if Metropolitan Peter were to abandon his duties as locum tenens, “our eyes will, of course, turn to the candidates indicated in [Patriarch Tikhon’s] testament, that is, to Metropolitan Kyrill and then to Your Eminence”; in other words, Metropolitan Sergius did not see any possibility for handing over the powers of deputy Patriarchal locum tenens.[5]Akty sviateishego Tikhona, patriarkha Moskovskogo i vseia Rossii: pozdneishie dokumenty i perepiska o kanonicheskom preemstve vysshei tserkovnoi vlasti. 1917-43 gg. [The Acts of His Holiness Tikhon, … Continue reading During the first period of his leadership of the Church, Metropolitan Sergius tried to steer it along the course of action he had inherited from Patriarch Tikhon and Metropolitan Peter, that is, the preservation of the Orthodox Church. Metropolitan Peter had left all “principal and general ecclesiastical matters” to be resolved by himself (see, for instance, Metropolitan Peter’s resolution of February January 19/February 1, 1926.[6]Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 437. Accordingly, in the matter of the Gregorianist Church Governance and Metropolitan Agathangel’s assumption of the leadership of the church, Metropolitan Sergius consulted his kyr-hierarch, Metropolitan Peter.

The fact that Metropolitan Sergius basically considered himself, rather than Vladyka Peter, to be Patriarchal locum tenens, was little known to anyone. One can see that Metropolitan Sergius had such an understanding from the fragment of his letter of June 13, 1926, to Metropolitan Agathangel. It is evident that it was Metropolitan Sergius’ reevaluation of his powers that led to the emergence of divisions in the Church (cf. the fragment from Metropolitan Peter’s letter of December, 1929, below).

Nevertheless, it can be said that, during the first period of his leadership, Metropolitan Sergius sought to fulfill the main mission of the locum tenens: to lead the Church up until the next Local Council, in which the will of the Church would be expressed in the election of a Patriarch as Her permanent head. Since the Church in the USSR did not have any legal status and could thus not assemble a council legally, as the “Living Church” party had done on more than one occasion, Metropolitan Sergius resorted to secret surveys of bishops. By November 1926, his envoys had surveyed all the bishops they were able to get to. 72 votes were cast for Metropolitan Kyrill of Kazan, an uncompromising servant of the Russian Church and the first Patriarchal deputy (according to Patriarch Tikhon’s will). There were several votes for the second candidate, and no more than one for Metropolitan Sergius.[7]Za Khrista postradavshie, p. 570. From the fact that the council of bishops of the Russian Church elected such a humble, uncompromising advocate for the truth, it is clear what path our archpastors wished to follow.

This election of Metropolitan Kyrill, which took place beyond the control of the authorities, alarmed the GPU greatly. Metropolitan Sergius was arrested. After Metropolitan Sergius’ arrest, his testament came into effect. Archbishop Seraphim (Samoilovich) of Uglich,[8]He assumed the leadership of the church at the decree of Metropolitan Joseph (Petrovykh) of Leningrad, who was unable to take up the duties of Patriarchal locum tenens. like Vladyka Agafangel in his own time, shifted the Church onto a decentralized basis (cf. Decree No. 362 of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon, the Holy Synod, and the Supreme Church Council). Mikhail Ivanovich Yaroslavskii, Vladyka Seraphim’s senior subdeacon, recalled about this time: “Vladyka told me that the authorities suggested that he, as head of the Church, [convene] a Synod. And they indicated whom he should appoint as members of the Synod. He did not consent to this…”[9]Vadimov, A. “Neizvestnoe svidetel’stvo o novom sviashchennoispovednike sviatitele Serafime” [“An Unknown Witness on New Hieroconfessor Seraphim”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox … Continue reading.

Archbishop Seraphim suggested including Metropolitan Kyrill in the Synod and refused, unlike Metropolitan Sergius, to decide on matters of principle on his own. The latter, based on his understanding of his powers as those of the chief bishop of the country, had set about deciding on such matters himself. One cannot avoid the suggestion that the GPU had “worked on” Metropolitan Sergius while he was under arrest. Perhaps here the quality of “faintness of heart” pointed out by Metropolitan Sergius’ mentor, Metropolitan Antony (Krapovitskii), and by the bishop-confessors Averky and Pachomy (cf. E. L. Episkopy ispovedniki [Bishop-Confessors], San Francisco, 1971), came into play. Metropolitan Antony said that Vladyka Sergius had a good heart but a weak will.

Second Term as Deputy to the Locum Tenens (1927-1944)

After his release in spring 1927, Metropolitan Sergius ceased consulting the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Church. A Synod was organized (selected) without Metropolitan Peter’s blessing and without the consent of a council of bishops, and in July, the so-called “Declaration” on the stance of the Orthodox Church vis-à-vis the government of the USSR, was published. It differed from Metropolitan Peter’s Declaration and from the letter to the government of the USSR from the bishops imprisoned in Solovki concentration camp. In December 1929, Metropolitan Peter wrote to his deputy, Metropolitan Sergius: “You have been accorded the power only to resolve current affairs and to be a guardian of the current order. […] In my instruction about appointing candidates as deputies, I did not deem it necessary to mention the limitations on their duties; there was no doubt for me that a deputy cannot overturn existing authorities, but can only deputize for them, serving, so to speak, as the central body through whom the locum tenens can communicate with his flock. The system of governance introduced by you precludes not only this, but also the very necessity for the existence of a

locum tenens

. [my emphasis —A.P.] The consciousness of the Church cannot approve such major steps… The current picture of divisions in the church is astonishing. My sense of duty and conscience do not allow me to remain indifferent to such a sorrowful phenomenon, and have given me cause to address Your Eminence with a most fervent request to correct this mistake, which has put the church in a humiliating position, leading to frictions and divisions within it and tarnishing the reputation of its leaders. Likewise, I request that you undo all other initiatives in which you have exceeded your powers.[10]Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 681.

No reply came to this letter, and in February 1930, Metropolitan Peter wrote to Metropolitan Sergius: “In my view, owing to the extraordinary conditions of Church life, in which normal procedures of governance are being subjected to various deviations, church life must be directed along the same path as it was during your first term as deputy. Please do return, then, to this line of conduct, which commanded the respect of all.[11]Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 691

Thus, Metropolitan Sergius, who was merely the pilot, but not the captain of the Russian Church, tried to lead it along his own path, instead of keeping to the previous, conciliar course of action. He thus placed himself and his self-proclaimed Synod in the same position vis-à-vis the Rusian Church as the Gregorianist bishops did their Temporary Supreme Church Governance (with the difference that the latter did not have an authoritative leader who was also Patriarchal locum tenens). As was mentioned above, the Gregorianist body was organized in December 1925 by a group of “Tikhonite” bishops for the alleged purpose of forestalling the troubles besetting the Church; however, it did not have the blessing of Metropolitan Peter and the bishops who had remained loyal to him, and despite its formal adherence to the established ways of the Church, its stance vis-à-vis the Soviet regime was of Renovationist ideological content and for this reason ended in schism.

Subsequently, despite manifold appeals by such venerable bishops of the Russian Church as Metropolitan Kyrill of Kazan (the first bishop designated in the list of Patriarchal locum tenentes), Metropolitan Agathangel (the most senior bishop in the Russian Church), Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy (Metropolitan Sergius’ kyr-hierarch), Metropolitan Antony of Kiev, and Metropolitan Joseph of Petrograd, Metropolitan Sergius began enacting new ecclesiastical policy. In his refusal to pay heed to his fellow brethren, we can very clearly see an impingement upon the principle of conciliarity and a difference from the time of Patriarch Tikhon, who did not violate the conscience of his faithful children. Moreover, the acceptance of the Soviet regime under Patriarch Tikhon was intended as merely formal, as the Bolsheviks themselves were able to sense perfectly well. Metropolitan Sergius went further than the Patriarch had by demanding that the people of the Church accept the Soviet authority not merely formally, but in their conscience. We see this confirmed in Metropolitan Sergius’ letter of July 8, 1935, to his delegate in North America, Archbishop Benjamin (Fedchenkov). “In the pledge [of loyalty —A.P.], what is important is not its formulation, or even the fact of the pledge, but that all the clergymen who are coming under your leadership should be well and fully aware of the fact that each and every one of them who feels entitled to make anti-Soviet proclamations should be deprived of his position under you and be excluded from the ranks of our clergy… It is by no means possible to give any cause for people to think that we are interested above all in the formal pledge and what happens in actual fact will be as it may. It is the other way around: what we need is real action, rather than a formal pledge [my emphasis —A.P.]”[12]Zhurnal Moskovskoi Patriarkhii (ZhMP) [Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate], No. 6, 1968.

Because their appeals to Metropolitan Sergius had no effect, over 70 out of approximately 200 bishops broke off ecclesial communion with gim, considering him to be overreaching himself as deputy, to have exceeded his powers, and to have led the Russian Church not along the narrow path of salvation, but rather by the ways of the world. This is especially clear from the fact that the Metropolitan Sergius’ course of action led to the justification of the use of lies in the Church in order to preserve her earthly organization. Sergianism can be considered to be this very phenomenon, the defense of the need to lie in order to preserve the earthly structure of the Church in times of trial.

Thus, none of the bishops who broke off communion with Metropolitan Sergius caused a schism by doing so. On the contrary, Metropolitan Sergius’ course of action initiated a schism. All the bishops who broke off communion with him, both in Russia and in the diaspora, continued to commemorate Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy, and it was through Metropolitan Peter that they remained in communion with the Universal Church. Unlike in the case of the Gregorianists, Metropolitan Peter did not impose any sanctions on the bishops who broke off communion with Metropolitan Sergius; on the contrary, in his two letters to Metropolitan Sergius, he appealed to him and exhorted him to return to the style of governance of his previous period, “which commanded the respect of all”, while expressing his sorrow in his second letter about the fact that “a multitude of the faithful refrain from entering churches in which your name is commemorated”. According to the resolutions of the Council of 1917-18, no sanctions could be imposed on any bishop who refused to accept some civil political position or another. The power to resolve such questions as those tackled by Metropolitan Sergius rested with the Patriarchal locum tenens himself, or, rather, with a local council of the Russian Church, for the principal task of the locum tenens is to steer the ship of the church that has been entrusted to him to the safe haven of the next local council. In his article “On the Powers of the Patriarchal Locum Tenens and His Deputy”[13]ZhMP, No. 1, 1931, Metropolitan Sergius wrote that his powers would cease with the death of the person for whom he was deputizing. Despite this, in December 1936, when he was informed of the death of Metropolitan Peter (who was actually still alive), Metropolitan Sergius appropriated for himself the powers of Patriarchal locum tenens. In 1937, the Synod of Bishops of the ROCOR conducted a thorough investigation into the current situation and judged Metropolitan Sergius to have usurped the powers of locum tenens, all the more so given that Metropolitan Kyrill of Kazan, who had been appointed as the first locum tenens by Patriarch Tikhon himself, was still alive.

One must keep in mind that in 1934, the Sergianist Synod bestowed the title of His Beatitude the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomenskoe upon Metropolitan Sergius, thus effectively placing him above Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy, his kyr-hierarch. For Moscow had come under the leadership of the Patriarch from the very beginning and had been a vacant see since Patriarch Tikhon’s death. The 1943 Synod of Bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate, which consisted of bishops who had accepted the Metropolitan Sergius’ course of action unequivocally (those who did not were not summoned out of exile), elected Metropolitan Sergius as Patriarch. A local council, which Metropolitan Sergius held up as a means for resolving all issues concerning the leadership of the Russian Church, and for which he had called upon all the scandalized bishops to wait, has to this day not yet been convened. All the councils that have taken place since 1943 have included only Sergianist bishops; none of the others were invited, as they had been excluded from the Moscow Patriarchate by Metropolitan Sergius.

In conclusion, it seems suitable to say (to borrow words from the book Those Who Suffered for Christ’s Sake) that when he ended up as acting primate of the Russian Church, Metropolitan Sergius – who was a major expert in what could be called “Dialectic Canon Law”[14]Dialectics being the art of debating and uncovering contradictions in the reasoning of one’s opponent. and could quickly and adeptly manipulate the church canons, documents, and facts one way or another in order to attain his goals – steered it on a new course without a conciliar verdict. Linked with this usurpation of power, apart from the canonical infractions, was the fact that, in order to preserve the outward organization of the church, the Moscow Patriarchate became an ally of a God-hating regime that made decisions about internal church affairs. The Moscow Patriarchate officially rejects the Holy New Martyrs and blames “certain circles within the Church” for preventing the Church from trusting the Soviet authorities (see, for example, Metropolitan Sergius’ Declaration). Until the end of his days, Metropolitan Sergius remained an eminent representative of the old theological school. This can be seen in the fact that even his letters in support of the Soviet authority have an ecclesiastical style. However, Metropolitan Sergius’ course of action did not grant the Moscow Patriarchate this desired freedom; its servants continued to be executed and its churches to be closed up to the beginning of the Second World War, and the majority of the churches that were still open under Stalin were taken away from the faithful by Khrushchev. All of this allows us to suggest that the course of action Metropolitan Segius chose for the Church turned into a personal tragedy for him. On May 15, 1944, Metropolitan Sergius, having been proclaimed Patriarch, died suddenly in Moscow at the age of 77 from a cerebral hemorrhage owing to arterial sclerosis.

References

| ↵1 | Dnevnik o zasedaniiakh vnov’ sformirovannogo sinoda 12 aprelia — 12 iiunia, 1917 g. [Diary on the Sessions of the Newly Formed Synod of April 12-June 12, 1917]. Moscow: Patriarchal Metochion of Krutitsy, 1995. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | , Hieromonk Damaskin (Orlovskii),. Mucheniki, ispovedniki i podvizhniki blagochestiia Russkoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi XX stoletiia [Martyrs, Confessors, and Strugglers for Piety in the Russian Orthodox Church in the 20th Century]. Vol. 2, p. 351 |

| ↵3 | Za Khrista postradavshie: goneniia na Russkuiu Pravoslavnuiu Tserkov’ 1917-1956 gg. [Those Who Suffered for Christ’s Sake: The Persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church from 1917-1956]. Moscow: Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox Institute, 1997, p. 34. |

| ↵4 | His immediate superior. |

| ↵5 | Akty sviateishego Tikhona, patriarkha Moskovskogo i vseia Rossii: pozdneishie dokumenty i perepiska o kanonicheskom preemstve vysshei tserkovnoi vlasti. 1917-43 gg. [The Acts of His Holiness Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia: Recent Documents and Correspondence on the Canonical Succession of the Supreme Church Governance, 1917-43]. Moscow: Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox Institute, 1994, p. 461 |

| ↵6 | Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 437. |

| ↵7 | Za Khrista postradavshie, p. 570. |

| ↵8 | He assumed the leadership of the church at the decree of Metropolitan Joseph (Petrovykh) of Leningrad, who was unable to take up the duties of Patriarchal locum tenens. |

| ↵9 | Vadimov, A. “Neizvestnoe svidetel’stvo o novom sviashchennoispovednike sviatitele Serafime” [“An Unknown Witness on New Hieroconfessor Seraphim”], in: Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia] No. 7, 1995. |

| ↵10 | Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 681. |

| ↵11 | Akty sviateishego Tikhona, p. 691 |

| ↵12 | Zhurnal Moskovskoi Patriarkhii (ZhMP) [Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate], No. 6, 1968 |

| ↵13 | ZhMP, No. 1, 1931 |

| ↵14 | Dialectics being the art of debating and uncovering contradictions in the reasoning of one’s opponent. |

Дорогой, о. Андрей. Благодарность Вам за хорошую статью о жизенном пути Митр. Сергия и о трагических событиях Российской Церкви в период после Октябрьского переворота. С фактами, приведенными Вам я вполне согласен, но не согласен с Вашими выводами, как с изложенными в этой статье, так и с продемонстрированными Вашим примером соединения с Сергианской Церковью в 2007 г. По прочтении статьи создается впечатление, что все предательство и обман Митр. Сергия нужно трактовать всего лишь как личную трагедию Мит. Сергия. “All of this allows us to suggest that the course of action Metropolitan Sergius chose for the Church turned into a personal tragedy for him”. Этакий Иван Сусанин наоборот: Сотворил раскол в Церкви, завел обманутое им стадо в советское болото, где нераскаянным и скончался. Да, это великая трагеди для него лично. Но это еще большая трагедия для всех, заведенных им в это болото. И болото не станет твердью даже, если 99% последоваших за отколовшимися в нем завязнут. Болото есть болото. покуда его не осушишь. Герой русской земли Иван Сусанин погиб, но он завел врага в болото. А несчатный Сергий завел на духовную погибель в болото своих. Ивану Сусанину подобает хвала, подобает ставить ему памятники. Но не подобает православным ставить азамаские и пр. памятники и окроплять их “патриаршей” рукой, оправдывая и продолжая веро-отступнический путь мит. Сергия, взятый им под чутким руководством ГПУ. Нынче это ФСБ. Сегодняшние плоды “личной трагедии” Мит. Сергия это сотни тысяч “личных трагедий” русских людей в России и у нас за рубежом, следуюших за сергианской иерархией МП. Вы, отче, образованный и знающий человек. Уверен, что Вам известно высказывание приснопямятного о. Константина Зайцева, которое любил цитировать, близкий ему по духу Святитель Филарет (Вознесенский) о том, что самая великая трагедия русского народа явилась в том, что вместо истинной исторической Российской Православной Церкви, им была подсунута лже-церковь, создание Сталина и ГПУ. А завершением этой трагедии явилось присоединение последнего остатка истинной исторической Российской Православной Церкви в лице РПЗЦ к сергианскому болоту, без какого то даже внешнего у МП покояния или хотя бы осознания отпадения Сергия и иже с ним. Т.е. осознания того, о чем Вы, отче, пишите в своей статье.

Чтобы помочь утопаюшим в болоте, в болото не прыгают, дабы не утонуть вместе с тонущими, но стоят на скале веры и протягивают утопаюшим, но жаждущим спасения, свой посох. Если бы Зарубежная Церковь в свое время поступила так, великая радость была бы в России и во всей вселенной. Но увы…

Вот и приходится многим русским людям теперь спасаться у старостильных греков, румын и в др. юрисдикциях, которые Господь и Его исповедники сохранили для ищющих Правды Его и спасения. Слава Богу за все!

Остаюсь Вашим доброжелателем.

Дъяков о. Иаков

Fr. Andrei, I agree with most of this article, and I am left wondering: why do you reprint it here when it clearly implies that the Moscow Patriarchate created by Metropolitan Sergius is schismatic? Yes, you make the valid point that until the death of Metropolitan Peter both the MP and the Catacomb Church recognized him as their canonical head (although Sergius de facto usurped his position). But Peter died in 1937. After that, there was no canonical or hierarchical bond joining the True Church of Russia – which was now in the Catacombs – from the schismatic church of the Moscow Patriarchate. I am glad you were able to publish this article, which accords with the position of ROCOR before 2000, before it fell away from the truth. But why are you publishing it now, when you have joined the schismatic MP?