On the evening of May 3, 1990, the following short announcement was issued to the press and wire services in Moscow:

“The Sacred Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church with profound sorrow announces that on 3 May 1990, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the Most Holy Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus, Pimen, fell asleep in God at the Patriarchal residence in Moscow.” [1] One Church 3, (1990).

His All-Holiness had been ill for some years, and his feebleness had been especially evident at public ceremonies during the millennial year of 1988. Although he had not been seen in public since the previous fall, the usual Christmas and Paschal Epistles had been published over his name. Not surprisingly, for a long time there had been speculation as to his successor — both within the Soviet Union and the Church Abroad.

Even in Russia, Pimen had often been seen as a weak puppet of the state, “accused of doing nothing,” and almost totally without opinions or a public “voice.” While it was acknowledged that both Church and Patriarch had “faced cruel and crude persecution,” many noted that Pimen had been overly zealous to “render unto Caesar…” [2] Editorial, Ibid. With his passing came renewed hope that, in the era of glasnost and perestroika, his successor would vigorously represent the Church’s interests.

When previous patriarchs had died earlier in the twentieth century, considerable time had lapsed before a successor was chosen — in the case of Pimen’s predecessor, Patriarch Aleksii, an entire year had passed. On this occasion, however, the Sacred Synod of Moscow seemed to leap into action, and on June 7, fess than five weeks after Pimen’s death, the Council of the Russian Orthodox Church elected as their new head an Estonian, Metropolitan Aleksii (Ridiger) of Leningrad and Novgorod, who was subsequently enthroned. Two critical questions immediately arose in the Church Abroad: 1) Was Patriarch Aleksii II freely elected, rather than appointed by the government and then “ratified’* by the council, as had been done with the previous three patriarchs? 2) What is his “character?” In essence, what can be expected of him, and can we work with him?

With regard to the election, a priest of the Church Abroad in Washington, D.C., Protopriest Victor Potapov, queried Archbishop Kiril of Smolensk, chairman of the Department of Foreign Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate. One week before the election, Potapov was told, “Your question concerning interference by the authorities in the procedure to elect the patriarch must be answered in the negative. It would just not be possible. I am profoundly convinced that, under the new conditions which exist in the Church… any attempts to exert pressure on the episcopate or on anybody would be costly…” [3] “Sorrowful Thoughts Regarding the Election of Alexis II,” in Parish Life, (July 1990). Implicit was an astonishing admission that previous patriarchs had not been freely elected.

Furthermore, Metropolitan Antonii (Bloom) of London, a member of the Moscow Patriarchate, declared that “if the [civil] authorities would influence the decisions of the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, in such an event the Council would be uncanonical and this would signify the end,” as he expressed it, “of the Moscow Patriarchate and its role in our new world.” [4] Ibid. This, of course, had been precisely the Synod Abroad’s objection to Patriarchs Sergii, Aleksii I, and Pimen — that they received their “exalted place” in the Church through government interference and were thus, ipso facto, uncanonical.

Following the election, Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) of the Orthodox Church in America (who had been present in Moscow at the time of the election and therefore privy to all the behind-the-scenes “talk”), confirmed that Patriarch Aleksii was indeed freely elected because, first, there had been many candidates and several secret ballots (unusual in itself), and, secondly and more importantly, the new patriarch is not of Russian blood (he is an Estonian of German descent) — an hitherto unheard-of development. “From my perspective,” Basil concluded, “this is a real victory for the Church.” [5] Ibid.

The Russian Synod Abroad, however, remained skeptical. As Fr. Victor Potapov observed, “It is hard to imagine that the atheists simply surrendered their position and let the Church decide unhindered such an important question as the election of a new Patriarch.” [6] Ibid. However, this opinion was clearly based upon psychological ambivalence, rather than factual evidence. The wariness born of decades of exile would not budge.

Patriarch Aleksii II’s character was also scrutinized by the Russian Church Abroad and, generally speaking, was found wanting. The most serious objection was based on 1974’s Furov Report, confidentially prepared for the Central Committee of the Communist Party by the deputy chairman of the Council for Religious Affairs. This document “rated all bishops according to their ‘trustworthiness’ in the eyes of the state. Aleksii II is ranked… [with] those bishops completely subordinated to state atheism who… realistically recognized that our state is not interested in elevating the role of religion and of the Church in society, and understanding this, they do not display any particular energy in spreading the influence of Orthodoxy.” [7] “In the Balance,” in Orthodox America 10, (June 1990). Additionally, other documents testified to “his willingness to denounce his fellow bishops, well beyond the call of duty.” [8] Ibid.

On the other hand, even though the Communist Party had rated him highly two years prior to his election, Aleksii II had outspokenly “lamented Communism’s mass murder of clergy and destruction of churches.” [9] Ibid. Furthermore, shortly after his election he announced that “the time has come to make a definite break with the past, when a priest was little more than a functionary.” [10] Ibid.

Exactly a month before the death of Patriarch Pimen, there had been unexpected but official stirrings in the long-slumbering Russian Church. On April 3, 1990, the Sacred Synod had issued an unexpected and detailed eight-page “Declaration” in which there was, for the first time since the death of Patriarch Tikhon (who has, not coincidentally, since been canonized by the Patriarchate) an open admission that the Church had been ill-served by her subservient attitude to the state. With unusual candor, the document spoke of the “persecutions” and “liquidation” policies of the state, of believers being “broken,” and tragic “compromises” by churchmen. It acknowledged that the Church had been severely weakened and clergy did not “always safeguard living ties with one another.” Although there is no sense of actual repentance for ecclesiastical mistakes and the compromises of the past, the declaration explicitly called for “genuine rebirth” in the Church, “serious reorganization,” and “profound changes.” [11] “Declaration of the Sacred Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church,” in One Church, op. cit.

This departed dramatically from the explicit propaganda that had appeared only a few years before. For example, in the 1982 book The Orthodox Church in Russia, published by the state solely for foreign consumption, we read that the Russian Church had willingly chosen an “inconspicuous” role that consisted of a “patriotic duty to instill within the young… a conscientious civic responsibility… and fervent service to the interests of [Soviet] society.” [12] Pitirim, Archbishop of Volokolomsk, ed. The Orthodox Church in Russia, 1982.

To date, as far as can be determined, the Church Abroad has had no official reaction to the remarkable Declaration of April 3, 1990. On the contrary, the Synod in Exile appears to have hardened its position concerning the Patriarchate, while at the same time taking advantage of new freedoms and possibilities within the Soviet Union.

In the 1980s, it was widely rumored that the Russian Church Abroad had secretly consecrated a catacomb bishop for Russia. Because of rapidly changing circumstances within the Soviet Union, this was finally confirmed in 1989. Bishop Lazarus, who had been secretly operating in the underground Church since 1982, emerged and openly took his place as the free leader of a quite remarkable new chapter in the history of Russian Orthodoxy.

Lazarus’s mother had died in the terrible famines of the 1930s. As a young man, he had joined one of the underground churches, where he had contact with many catacomb figures — extraordinary elders (startsi), pious wanderers or pilgrims, and simple believers. During this time he was secretly tonsured a monk, but in 1950, at the age of nineteen, he was arrested, tortured, and imprisoned for five years because he belonged to an illegal group that refused to recognize the Stalinist “election” of Patriarch Aleksii I.

Upon his release, he immediately joined a catacomb church that believed grace still remained with the Moscow Patriarchate — “because, dogmatically, there were no violations concerning the Orthodox teaching about the Holy Trinity and the Mysteries [sacraments] were performed according to the rules of the office” — but which refused to accept the canonical legitimacy of the Patriarchate. [13] Orthodox America, op. cit.

Although Bishop Lazarus, following his secret consecration in 1982, continued his hidden work in the catacomb movement, the situation in the Soviet Union — now known politically as the Commonwealth of Independent States — has changed so dramatically that he and his followers are now operating openly, with little or no fear of reprisal under the current circumstances. It is believed that there may be as many as a score of parishes and clergy (and the number is growing rapidly) — many of whom have left the ranks of the Patriarchate — that consider Lazarus their bishop and commemorate as their chief shepherd not Patriarch Aleksii II, but Metropolitan Vitalii of the Church Abroad.

However, while acknowledging the high moral authority of the Church Abroad, at least one believer in the Soviet Union (evidently a lay member of the Patriarchate) expressed grave reservations about this development. Writing on May 14, 1990, this individual, who requested anonymity, begged the Church in Exile not to create any further divisions than already existed:

“Today there is nothing more terrifying for Russia and for its church people than schism. The country today stands on the verge of civil dismemberment. Only the one Orthodox Church can… save the people and the country from historic ruin… We repeat: the situation in the government and in the Church is extremely unstable. It is possible that soon circum-stances will tum in such a way that the opening of parishes of the Church Abroad in the territory of Russia will be a necessary step. But today, it would be a mistake which would only anger the Moscow Patriarchate and move it to take retaliatory action.”

Meanwhile, at a meeting held in the first week of May 1990, the bishops in exile had already presented their reasons for making such a significant incursion into the territory of the Mother Church: the Church Abroad was opening these parishes precisely in response to urgent requests from some clergy and laity belonging to the Patriarchate and others in the catacomb Church, who

“…are appealing to us to cover them with our omophorion, to impart grace to them. Our pastoral conscience tells us that we not only can, but we must help them, investigating in each case the reasons which impel them to tum to us. However, we are approaching this, our new ministry, with great caution, trusting in the help of God, for what is impossible for man is possible for God.” [14] “Out From the Catacombs,” in Orthodox America, op. cit.

As one Synod publication expressed it:

“Clearly, this era of glasnost has seen a number of positive developments with regard to Church life in the Soviet Union… Nevertheless, contrary to popular demand that the Moscow Patriarchate disassociate itself completely from State interferences [as the Romanian Orthodox Patriarchate had just recently done], the present hierarchy shows no intention of liberating itself from its “sweet captivity.” [15] “The Church Abroad in Russia,” in Orthodox America, op. cit.

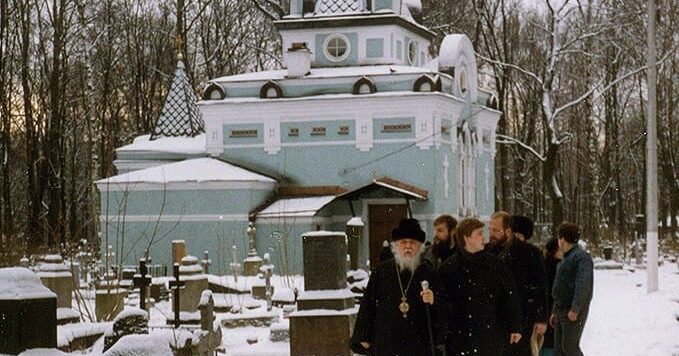

Although it would have been completely unheard of only a year or two before, in the summer of 1990 two hierarchs of the Russian Church Abroad, Bishop Hilarion of Manhattan and Bishop Mark of Germany, went to the Soviet Union openly and unimpeded, and concelebrated with Bishop Lazarus in St. Constantine’s Church in the historic village of Suzdal. The clergy of this parish, together with an estimated 5,000 parishioners, were received into the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad. By early 1991, it was expected that the “Free Russian Orthodox Church” (those in the Soviet Union belonging to the Church Abroad) should have its own parish in St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad).

Thus, in the eighth decade of her long and hard sojourn in exile, the Church Abroad finds herself at an unexpected moment in history. Having survived decimation through two world wars and many schisms, having lost many of her English-language mission parishes and clergy, there has now suddenly opened up new, if very dangerous, possibilities for the near future, the shape of which no one can begin to perceive. Meeting this future will require immense wisdom and grace. It also demands discernment on the part of the leaders of the Russian Church Abroad—the ability to see beyond the hurts, wounds, and fears of the past, to separate wishful thinking from reality, and mean-spirited gossip from facts. Finally, a successful future requires a strong dose of clearheaded thinking, coupled with a broad and deep vision that is unconditionally and generously open to the promptings of the Holy Spirit. All of this remains yet in the future, and in the hands of God.

References

| ↵1 | One Church 3, (1990). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Editorial, Ibid. |

| ↵3 | “Sorrowful Thoughts Regarding the Election of Alexis II,” in Parish Life, (July 1990). |

| ↵4 | Ibid. |

| ↵5 | Ibid. |

| ↵6 | Ibid. |

| ↵7 | “In the Balance,” in Orthodox America 10, (June 1990). |

| ↵8 | Ibid. |

| ↵9 | Ibid. |

| ↵10 | Ibid. |

| ↵11 | “Declaration of the Sacred Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church,” in One Church, op. cit. |

| ↵12 | Pitirim, Archbishop of Volokolomsk, ed. The Orthodox Church in Russia, 1982. |

| ↵13 | Orthodox America, op. cit. |

| ↵14 | “Out From the Catacombs,” in Orthodox America, op. cit. |

| ↵15 | “The Church Abroad in Russia,” in Orthodox America, op. cit. |