On March 2, 1917 (March 15, New Calendar), [1] According to the Julian Calendar, this date would be March 15; however, because the Russian Orthodox Church adheres to the Gregorian Calendar, the dates used herein are those of the Old Calendar. Tsar Nikolai II abdicated in favor of the authority of the Provisional government. The Holy Synod, as a “ministry” of the tsarist government, was abolished. Although it had been contemplated for several years, the Church now moved swiftly to summon an All-Russian Council, or Great Sobor, which met in Moscow even as the Bolsheviks were seizing power in October and November of 1917.

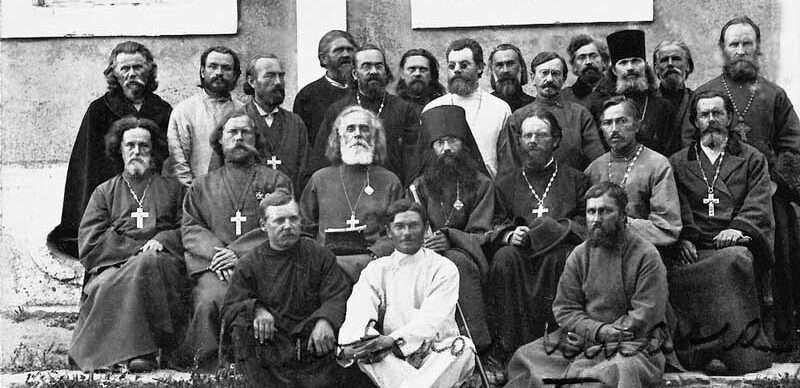

High on the agenda for this All-Russian Sobor was the restoration of the Patriarchate. The secular center of union for the nation, the throne, had been cast down, but the Church hoped to restore this center in the person of a patriarch. Among the top three candidates nominated by ballot were Archbishop Tikhon (Belavin), formerly chief hierarch in America, and Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) of Kharkov, the future first hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. After Tikhon was chosen by lot, he began his tragic patriarchy with these prophetic words:

“Your news concerning my election for Patriarch is for me that scroll on which was written ‘Lamentation and mourning and woe’ (Ez. 2:19)… How many tears will I have to swallow; to how many sighs of mourning will I give utterance in the patriarchal ministry which lies before me?” [2] Orthodox Life, (May/June 1981).

The “widowship” of the Russian Church was at an end, but far worse trials were to come.

In spite of the foreboding political conditions, Metropolitan Anastasii (Gribanovskii), the future second leader of the Church Outside Russia, was delegated to do research and recreate the ancient ceremony for the enthroning of the new patriarch. This he did with a scholar’s accuracy and a believer’s love so that, for the first time in more than two centuries, the faithful of Moscow were able to witness the glorious enthroning of an “All-Holy One.”

The All Russian Sobor defined itself as the “supreme legislative, administrative, judicial, and auditing authority” under the patriarch, who was described as primus inter pares among bishops. [3] Pospielovskii, Dimitrii, The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime: 1917-1982, p. 35. The sobor also restored the older practice of having bishops elected by clergy and laity in each diocese.

The Russian government, now Communist and led by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, was quick to move against the Church, secularizing marriage, nationalizing property, seizing funds, and officially separating it from the state. Between 1918 and 1920, tens of thousands of believers were murdered, including twenty-eight bishops and thousands of priests. This, however, was only the beginning of a reign of terror. Patriarch Tikhon responded firmly. On January 19, 1918, he formally condemned the terrorism against the Sacraments and anathematized the Communist government.

Five months later, on May 6, 1919, about thirty bishops in southeastern Russia’s Caucasus region, finding themselves in a chaotic political situation and in irregular contact with the Patriarch, formed a Temporary Highest Church Administration in order to guide the affairs of the Church in their area. In October, Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) presided over a sobor of this administration, which appointed Metropolitan Anastasii (Gribanovskii) as its representative to the Ecumenical Throne of Constantinople. Almost immediately, however, six bishops, including Metropolitans Antonii and Anastasii, had to flee the approaching Red Army. This caused some later criticism, for Church canons ordinarily require a bishop to be “wedded” to his diocese. Reportedly, many other Russian hierarchs either were unable to flee, and willingly embraced martyrdom, or chose not to leave (one of the latter was Bishop Aleksii [Simanskii], a future puppet-patriarch of Moscow).

Nonetheless, the fleeing bishops took refuge in Constantinople where, on November 1, 1919 [In fact December 1920 – Editor], and with the blessing of locum tenens Dórotheos of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, they formed the Highest Russian Church Administration Abroad, agreeing that the Ecumenical Patriarchate could assume responsibility “to supervise and administer the Church life of Russian communities abroad both in non-Ortho- dox and Orthodox countries.” [4] Ibid., p. 114.

At this distance, and with conflicting facts, it is difficult to know precisely what Patriarch Tikhon thought of all this. Some of his actions seem to indicate that he saw the decisions made in Constantinople as wise and practical. He also appeared to implicitly confirm each of their decisions when he issued, on November 20, 1920, the famous Ukaz No. 362, which reads, in part:

“If a diocese should find itself cut off from the Highest Church Administration, or if the Highest Church Administration itself, headed by the Holy Patriarch, should for any reason cease its activity, then the diocesan bishop should immediately enter into relations with the bishops of the neighboring dioceses with the aim of organizing a body to serve as a supreme authority… In case this should prove impossible, the diocesan bishop takes on himself the totality of authority.” [5] A History of the Russian Church Abroad…, op. cit., p. 13. (See Appendix V for the full text of the decree, [italics added])

The problem with this decree is that it was published before Patriarch Tikhon had heard of the events in far-off Constantinople, and it seemed actually to apply to circumstances within the boundaries of Russia — then known politically as the Soviet Union — not outside. However, one can reasonably argue that the principle would be the same in any case, and that the Patriarch, were he in full possession of all the facts, would have explicitly confirmed the decisions made in Constantinople.

In any case, this document came to be regarded by Emigre Russians as the canonical foundation of what is called today “The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.” Few disputed this at the time, for throughout 1921, every Russian bishop outside of the Soviet Union entered into the Highest Administration Abroad. Its authority included the United States, Western Europe, and, later, Asia, and was endorsed by the patriarchs of both Constantinople and Serbia. Cordial contacts were also established with the self-governing Churches of Bulgaria and Greece.

Late in 1921, at the invitation of the Patriarch of Serbia, the Highest Church Administration moved its headquarters to Karlovci, Yugoslavia (now Karlovac, Croatia), where a Sobor of thirteen bishops and many other clergy and laymen immediately convened, proclaiming loyalty and submission to the Patriarch of Moscow and adding that “the duty of those of us abroad, who have persevered our lives in the dispersion and have not known the flames which are destroying our land and its people, is to be united in the Christian spirit, gathered under the Sign of the Cross of the Lord, under the protection of the Orthodox Faith.” [6] Ibid., p. 17. This sobor also called for the restoration of the Romanov dynasty in Russia and named Metropolitan Antonii “Vice-regent of the All-Russian Patriarch.” [7] The Russian Church Under…, op. cit., p. 119.

On March 15, 1922, however, the Communists placed Patriarch Tikhon under house arrest. The following September, the Highest Administration received a new ukaz, allegedly promulgated by the Patriarch on May 5 (while he was still under arrest), ordering the immediate suppression of the Highest Administration “because it has dared to engage in politics in the name of the Church.” [8] A History of the Russian Church Abroad…, op. cit., p. 23. The Patriarch then placed the Russian parishes of Europe under Metropolitan Evlogii in Paris. This came as a shock, and for a period of time there was considerable debate about whether or not this decree was legitimate and should be obeyed.

A sobor was again summoned and, out of “filial obedience,” the Highest Russian Church Administration Abroad was indeed dissolved. But because most believed that the Patriarch’s order had been written under Soviet pressure, a new organization was created, the Temporary Holy Episcopal Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, “until such time as the Patriarch should be liberated and could freely explain his decree.” [9] Ibid., p. 25. The following year, still another sobor confirmed all this and instituted a permanent governing Synod with Metropolitan Antonii as its chairman.

Critics of the Russian Church Abroad have questioned whether Patriarch Tikhon’s decree was really composed under Soviet pressure since, during his imprisonment, he had courageously refused to recognize the Soviet-sponsored “Renovationist” Sobor of 1923. If he had been able to stand up to the Communists in that regard, then why not also where the integrity and survival of the emigre Church were concerned?

One should also note that during this confusing period, Metropolitan Antonii expressed a desire to retire to Mount Athos in Greece. The reason for this is unclear. Critics say that the Metropolitan initially believed that the ukaz should be obeyed and all parishes given to Metropolitan Evlogii in Paris. But when Mount Athos declined to accept him, and Evlogii himself declared that the ukaz was too suspicious to be obeyed, “…a considerable part of the emigration forced him [Metropolitan Antonii] to renounce his intentions and remain at the helm of the Synod.” [/ref] Ibid., p. 27. [/ref]

Because the exiled Synod could only meet once a year, its daily activities were supervised by lay officials of the powerful Supreme Monarchist Council, which later was to include the influential Count George Grabbe.

At this point, the use of names, both official and unofficial, for the exiled Russian Church should be clarified. Early titles were long and unwieldy. In official documents today, the Church is usually referred to as “The Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia” or “The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad.” Less formally, it is sometimes called “The Russian Church (or Synod of Bishops) in Exile” or, in abbreviated Russian form, Zarubezhnaya (literally, “Exiled”). Most commonly, however, it is simply called “The Synod.” Still, critics sometimes insist on referring to the Church Abroad as the “Karlovci Synod,” whose adherents are called “Karlovciites” after the Yugoslavian city where the Church headquarters was located for nearly thirty years.

In the mid-1920s, the Temporary Holy Episcopal Synod declared that, in view of the murky situation surrounding the Patriarch in Moscow, “in future cases, those orders from His Holiness relating to the Orthodox Church Abroad which would be insulting to her honor and bearing clear features of direct pressure upon the Holy Patriarch’s conscience on the part of Christ’s foes, should be ignored as originating not from the Patriarch’s will, but from a completely different will. At the same time, full respect and devotion should be rendered to the person of the innocently suffering Holy Patriarch.” [10] The Russian Church Under…, op. cit., p. 121.

Count George Grabbe (who would later become known as Bishop Gregorii in the United States) wrote: “The Russian Orthodox Church [both inside and outside the Soviet Union], by the Providence of God, has been placed, of necessity, to live in a realm of an entirely unusual sort…” [11] Orthodox Life, (November/December 1979). This was why Priestmonk Seraphim Rose, speaking to the enslaved Russian Church about the “order” to dissolve the Church Abroad, said:

“Thus, some people can find themselves in a position that may be “legally correct” but is at the same time profoundly un-Christian — as if the Christian conscience is compelled to obey any [italics added] com-mand of the church authorities, as long as these authorities are properly “canonical.” This [is a] blind concept of obedience for its own sake.” [12] Andreyev, Ivan, Russia’s Catacomb Saints: Lives of the New Martyrs, p. 257.

References

| ↵1 | According to the Julian Calendar, this date would be March 15; however, because the Russian Orthodox Church adheres to the Gregorian Calendar, the dates used herein are those of the Old Calendar. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Orthodox Life, (May/June 1981). |

| ↵3 | Pospielovskii, Dimitrii, The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime: 1917-1982, p. 35. |

| ↵4 | Ibid., p. 114. |

| ↵5 | A History of the Russian Church Abroad…, op. cit., p. 13. |

| ↵6 | Ibid., p. 17. |

| ↵7 | The Russian Church Under…, op. cit., p. 119. |

| ↵8 | A History of the Russian Church Abroad…, op. cit., p. 23. |

| ↵9 | Ibid., p. 25. |

| ↵10 | The Russian Church Under…, op. cit., p. 121. |

| ↵11 | Orthodox Life, (November/December 1979). |

| ↵12 | Andreyev, Ivan, Russia’s Catacomb Saints: Lives of the New Martyrs, p. 257. |