988 Baptism of Russia.

1054 The Great Schism between Eastern and Western Churches begins.

1326 Ruling See of Russia is transferred to Moscow.

1439 The “False Council” of Florence takes place.

1589 Patriarchate of Moscow is established.

1660 Beginning of Old Believer Schism.

1721 Tsar Peter I replaces Patriarchate with a Holy Synod.

1790 First Russian Orthodox clergy comes to North America via present-day Alaska.

1870 First Russian parish in U.S. is founded in New York City.

1872 North American Diocese in Aleutia and Alaska established by Moscow.

1898 Arrival in North America of Archbishop Tikhon (the future patriarch of Moscow).

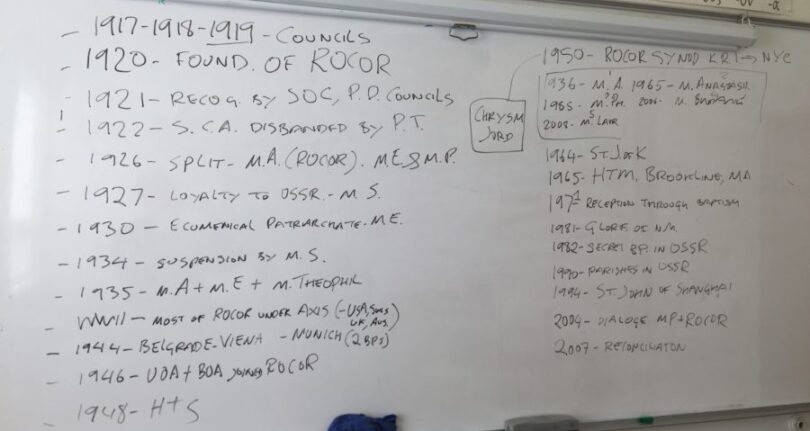

1917 Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II on March 2 (March 15, New Calendar). All-Russian Sober restores Patriarchate in the person of Archbishop Tikhon.

1919 Exiled bishops form “Temporary Highest Church Administration” of Church Abroad.

1920 Patriarch Tikhon issues Ukaz No. 362.

1921 Headquarters of “Highest Church Administration” moved to Karlovci (Karlovac), Yugoslavia.

1925 Patriarch Tikhon dies; Metropolitan Petr assumes administration, followed quickly by Metropolitan Sergii.

1927 Metropolitan Sergii demands oaths of loyalty from those in exile. First “American Schism” from Church Abroad begins.

1928 Metropolitan Sergii condemns and expels Church Abroad.

1933 Metropolitan Sergii declares American Church schismatic.

1934 Metropolitan Antonii (Khrapovitskii) retires and Anastasii (Gribanovskii) becomes his “substitute.”

1935 American Church rejoins Church Abroad.

1936 Metropolitan Antonii dies and is succeeded by Anastasii.

1943 Metropolitan Sergii becomes patriarch of Moscow.

1944 Patriarch Sergii dies after a few months in office.

1945 Newly elected Patriarch Aleksii I (Simanskii) woos American Church.

1946 Second “American Schism” begins.

1950 Metropolitan Anastasii moves headquarters to New York.

1964 Metropolitan Anastasii retires and is succeeded by Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesenskii).

1965 Metropolitan Anastasii dies. Metropolitan Philaret appeals to Patriarch of Constantinople not to compromise with the Roman Church.

1970 Patriarch Aleksii I dies.

1971 Metropolitan Pimen elected new Patriarch of Russia.

1981 The New Martyrs and Imperial Family are canonized in a special ceremony in New York.

1983 The Church Abroad issues its Anathema against Ecumenism.

1985 Metropolitan Philaret dies.

1986 Vitalii (Ustinov) becomes Metropolitan. The “Greek Schism,” led by Archimandrite Panteleimon, begins.

1988 Millennial celebration of one thousand years of Orthodox Chris-tianity in Russia.

1990 Patriarch Pimen dies, and is succeeded by Aleksii II (Ridiger).

Introduction

On June 7, 1981, something unusual happened at the annual Commencement Exercises for the Holy Trinity Seminary of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, located in upstate New York. This bastion of maleness — for the seminary shares facilities with a monastery of some scores of monks and is an intense enclave of Old Russian Orthodox traditions, customs, and languages — was addressed by a non-Russian, non-Orthodox woman, Suzanne Massie, author of Land of the Firebird: The Beauty of Old Russia. The wife of Robert K. Massie, she and her husband were co-authors of the bestselling biography of the last tsar and tsarina, Nicholas and Alexandra, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Peter the Great.

Recognized as the foremost Western interpreters of Russian aesthetics (religious art and architecture) and history, the Massies’ great appreciation for “things Russian” began when they learned that the last Romanov heir, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, suffered from hemophilia, just as did their own son. In Land of the Firebird, Suzanne Massie had acknowledged that “over the years, I found joy and inspiration in Russian poetry, prose, art, architecture, music, dance, and even the sound of the language.” [1] Massie, Suzanne, Land of the Firebird, p. 13. She had seen and understood, to a degree that few non-Orthodox have, the rich and complex weave of Eastern Orthodoxy in the tapestry of Russian culture and history — which she believes is personified in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. She thus drew the attention of Russian Orthodox leaders living in exile, who asked her to address the 1981 graduating seminary class.

On that occasion, she observed:

“Russia can help to provide us with that nourishment we so much need [in the West]… You in the Orthodox Faith are, for Russia, the living link between the past and the future, and for us in America, an essential connection between East and West. As a Westerner, step by step, I have been led closer to you.

Thanks to my contact with Russian culture and the Russian Church, my life has been enriched so greatly that I cannot imagine it without you… I have learned to trust mystery.” [2] Orthodox Life, (July/August 1981).

Indeed, this is why one Orthodox convert (now a priest-monk at Holy Trinity Monastery) wrote that the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia “preserves the spirit of Old Russia and we, the faithful, of whatever culture or background, have to strive to meet the standard set by the faithful of the past when Orthodoxy was a way of life.” [3] Orthodox Life, (May/June 1982).

On one level, then, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia preserves the best of “old Holy Russia.” At the same time, it also represents the historic and Apostolic Church of Christ in its Slavic expression, while on still another level — technically, canonically — it “is that part of the Russian state and at the present time is headed by a Chief Hierarch and a Synod of Bishops which are chosen by the Sobor or Bishops of the Russian Diaspora.” [4] Orthodox Word, (March/April 1971).

To understand how all of this came to be, however, we must look briefly at the history of Orthodoxy in Russia — and in North America — before the Russian Revolution of 1917-18.

***

The year 1988 marked the millennium of Russian Orthodoxy. In the year 988, Grand Duke Vladimir of Kiev brought the Orthodox Faith to his people from the Byzantine Empire, thus wedding historic Orthodox doctrine and practice to the Slavic “soul.” That “soul” has a certain rough quality, a “chaotic element, the exuberance of feelings and sometimes even revolt against all established order, against all law and regulation” — very similar, in fact, to our Western mentality in the latter half of the twentieth century. But “that chaotic element was counterbalanced by the settled pattern of religious usage and customs, by the framework of the Church’s ritual, by family traditions sanctified by the religious life… an ideal developed out of a spiritual discipline influencing both the soul and also outward behavior… a spiritual order imparting a religious beauty [italics added] to the whole of one’s conduct and manner of life.” [5] Arseniev, Nicholas, Russian Piety, p. 48.

In the tenth century, the Russian Church was simply another diocese — albeit a rather large and distant one — of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Patriarch selected and consecrated its Metropolitan with the title “of Kiev and All Rus.” In 1326, this Metropolitan See was transferred to Moscow, the new capital of Russia.

Contrary to popular Western notions, the tsar was never “Head of the Church” — as English monarchs became in the sixteenth century — but was only the “defender of the sacred dogmas and the good order of the Holy Church.” [6] Orthodox Life, (May/June 1981). To the degree that he lived by the Gospel, thus he was accepted as protector and defender, but if he stepped outside this boundary — as did, for example, Tsar Ivan IV (“The Terrible”) — he was subject to the same judgment and censure as any peasant.

Following the “False Union” of the Eastern Churches with Rome at the Council of Florence in 1439, the Russian representative to the council, Metropolitan Isidor, was deposed by Grand Prince Vasilii II and the Union with Rome was decisively rejected. In 1448, the Russian Hierarchs elected their own Metropolitan, St. Iona (Jonah), for the first time without the participation of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Thus, when the Byzantine Empire fell to the Turks in 1453, the Russian Church logically assumed leadership of the Orthodox world and the tsar came to be regarded as “Emperor of all Christians.”

In 1589, Patriarch Hieremias II (Jeremiah) of Constantinople established a separate Patriarchate for Russia and elevated Metropolitan lob of Moscow to this throne. However, under Tsar Peter the Great, who wanted greatly to westernize Russia, including its government, culture and church, the Patriarchate was deliberately allowed to remain vacant when Patriarch Adrian died in 1700, being ruled by the locum tenens, Metropolitan Stefan Iavorskii, for the next twenty-one years. Eventually, in 1721, Peter replaced the Patriarchate with a Holy Synod, whose administrative officer, or chief procurator, was a layman responsible to the state. Without a patriarch, the Russian Church considered herself “widowed.” “Deprived of a personal, unifying, spiritual center… her capacity for beneficial influence on the people was bound.” [7] Ibid.

Although the Russian Church remained “widowed” until the Russian Revolution of 1917-18, she was nonetheless active in her own sphere, opening vast missionary territories in Siberia and elsewhere. By 1794, this included the northwestern-most part of North America — present-day Alaska — where numerous Aleut Indians and Eskimos were converted to Orthodoxy. The first Russian Orthodox parish in the continental United States was founded in New York City in 1870, and in 1872, the Holy Synod of Moscow established the diocese of Aleutia and Alaska, with a cathedral in San Francisco.

In 1898, the bishop of this diocese was Tikhon, who later became the patriarch of All Russia. Until his return to Russia in 1907, he worked energetically and established (with the help of two suffragan bishops) more than twenty-four parishes in North America, as well as a seminary. But Archbishop Tikhon was even more concerned about the spirituality of his flock. Quite early on, he identified and described a problem that would haunt the Church throughout all of the next century:

“We do occasionally meet sons of the Church who are obedient to her decree, who honor their spiritual pastors, love the Church of God and the beauty of its exterior, who are eager to attend to its divine service and to lead a good life, who recognize their human failings and sincerely repent of their sins. But are there many such among us? Are there not more people… who were born, raised, and glorified by the Lord in the Orthodox Faith, yet who deny their faith, pay no attention to the teachings of the Church, do not keep its injunctions, do not listen to their spiritual pastors and remain cold towards the divine service and the Church of God? How speedily some of us lose the Orthodox Faith in this country of many creeds and tribes!” [8] Orthodox Life, (January/February 1988). [italics added]

Under Archbishop Tikhon’s wise episcopacy, the diocesan center was moved from San Francisco to New York City. Forty more parishes were founded under his successor, Archbishop Platon (1907-1914), and still another thirty-five were added during the reign of Archbishop Evdokim (1914-1917).

With the cooperation of Patriarch Ióakeim III of Constantinople, Archbishop Tikhon and his successors called for “the establishment of an American Orthodox Exarchate which was to be governed by a synod of the bishops of various racial or national groups” in order to gradually create “a strong American Orthodox Church… under the watchful guidance of the Russian Church.” [9] Holy Transfiguration Monastery, A History of the Russian Church Abroad and the Events Leading to the American Metropoliss Autocephaly, p. 6. This noble vision, however, was utterly shattered by the events of the Russian Revolution.

It is against this background that the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia came into existence.

References

| ↵1 | Massie, Suzanne, Land of the Firebird, p. 13. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Orthodox Life, (July/August 1981). |

| ↵3 | Orthodox Life, (May/June 1982). |

| ↵4 | Orthodox Word, (March/April 1971). |

| ↵5 | Arseniev, Nicholas, Russian Piety, p. 48. |

| ↵6 | Orthodox Life, (May/June 1981). |

| ↵7 | Ibid. |

| ↵8 | Orthodox Life, (January/February 1988). |

| ↵9 | Holy Transfiguration Monastery, A History of the Russian Church Abroad and the Events Leading to the American Metropoliss Autocephaly, p. 6. |