Part IV, Chapter 5

Church Schools

In all of the larger communities, the Church Abroad maintains parish schools, in which, along with religious instruction, instruction in the Russian language, literature, history, geography, and other subjects is given. The goal of these schools is the dissemination and preservation of the Orthodox Faith among the youth and their upbringing as active and faithful members of their parishes. Through the spread of practical subjects — a type of Russian national knowledge — the children of the émigrés are made aware of the fact that Russia is their homeland, from which their parents and grandparents were driven, and to which many of them hope to return one day. Thus, they must not feel that they would be strangers in a future Orthodox Russia: language, history, and culture bring them closer to their old homeland.

Giving religious instruction to the émigré children has been necessary since the flight from Russia so that the adolescent youth remain bound to the Russian Orthodox Church. The majority of émigrés found themselves in non-Orthodox countries. The Russian emigration did not want to forfeit their national identity and their Faith in these countries; therefore, the youth, in particular, must be entrusted with the positive values of pre-Revolutionary Russia. For them, the danger of assimilation through school attendance in the host countries was particularly great.

This applied to the first wave of emigration as much as to the second (after 1945). One more circumstance was added to the second emigration: their younger generation, which had grown up under the Soviet regime, had had no opportunity other than within the family to become acquainted with the Christian beliefs and truths because, since 1918, religious instruction was banned from schools. In addition, any organized form of religious instruction by the Church was forbidden. Among the adults themselves, many had lost contact with the Church because, until the outbreak of World War II, almost all the churches in the country had been closed. In practice, a whole generation had grown up, whose education and upbringing had been stamped by the Marxist worldview and who lacked any connection with the classic Russian education. [1]In Russia after the Revolution, the entire educational system was revamped in accordance with the Marxist-atheist worldview. Some things representing the old culture were destroyed, others were … Continue reading That the emigration has nevertheless succeeded in preserving the Russian language and culture among the Russian youth until the present day — one should not forget that present youth are already the second or third generation to grow up abroad — is first of all to the credit of the Russian Church Abroad, which has, in its parish schools today, familiarized the youth with the classical values of the culture. The Church Abroad has always understood itself to be the Church of émigré Russians, and only in second place as the Church of those baptized Russian Orthodox, even if in a few communities today after 70 years in the emigration the Liturgy is already celebrated in English, German, French and other languages. This is, however, more a result of mission in the host countries than a consequence of assimilation. In contrast to the OCA (Metropolia), [2]The Metropolia was the first to initiate the development of church Sunday schools, in which instruction was given in English and which concentrated on catechism. In 1953 there were 76 such Sunday … Continue reading which is of Russian origin but is concerned with the assimilation of the faithful and strives to unite all the descendants of Orthodox immigrants, thus using English as the liturgical language while abandoning Church Slavonic, the Church Abroad is concerned with the preservation of the Russian language and culture and rejects to far-reaching an assimilation.

That part of the emigration that has organized itself under the leadership of the Church Abroad has understood itself to be as much the preserver of religious, ecclesiastical heritage as the preserver of the Russian national and cultural heritage. This is not only the success of the Church Abroad, but rather more proof of the justification for its existence. Certainly, the Church Abroad will exist as long as the Russian émigrés hold fast to their national identities. [3]Fr. Johannes Chrysostomus repeatedly prophesied the demise of the Church Abroad without ever having established this in full; compare his essays “Patriarch Tichon” and “Die Russisch-Orthodoxe … Continue reading On the subject of Russian secondary and tertiary schools that exist in the emigration, a distinction must be made between schools that were founded upon the Church’s initiative and those that came into existence with the help of government and social organizations. To the latter belong, for example, many Russian high schools that existed in the 1920s and 1940s, and institutions of higher learning such as the “Russian Law Faculty” and the “Economic Institute”, both in Prague. These institutions wanted to guarantee academic studies (independent of a non-Russian world view) and to give Russian students the opportunity to study at their own educational institutions. The many high schools that were founded in the 1920s and 1940s pursued the goal of making it possible for those pupils, who had begun their education in the Soviet Union and had interrupted it on account of their flight, to receive a diploma. Because they did not speak the language of the countries that received them, they either would have had to give up their studies entirely or interrupt them for a long period of time. Thus, primarily with the support of government agencies and international refugee organizations, their own school system came into being. Most of these institutions only existed for a few years and were then dismantled.

In order to prevent émigré children from losing their national identity and their faith, the Church Abroad concerned itself with establishing its own school system. The Church started with catechismal instruction, which was given in groups. From these religious lessons, the clergy then gradually developed the Church schools that exist today, after they recognized that without instruction in Russian language, literature, history, and other subjects the children would lose their national Russian identity.

Besides the schools that the émigrés founded, there were also the schools that had been founded by the ecclesiastical missions before the Revolution. They were either closed during World War I or integrated into the local school systems. The Peking Ecclesiastical Mission had maintained 17 boys’ schools and 3 girls’ schools. They also continued to exist after 1918, under the direction of the Church Abroad and received state support. The Korean Mission maintained 7 schools; in Japan, there were 2 schools; and the Mission in Urmia (Persia) had 1 school. The largest school network, with approximately 93 schools, was in Palestine and Syria, for the Arab Orthodox population. It was financed by the “Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society,” which also provided the means for its own teaching seminars and development for those who taught at these schools. [4] Seide, Jerusalemer Mission; Idem., Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in China. These schools were almost all taken over by the countries in which they were located, and were integrated into the national school system, thereby losing their status as Orthodox schools.

The Church hierarchy devoted great attention to schooling and group activities (unions). This is emphasized by the fact that the Councils of Bishops and the three Pan-Diaspora Councils discussed in detail youth and group work. At the First Pan-Diaspora Council, this problem received little recognition, because it was still believed that the emigration was temporary; however, at the Second and Third Pan-Diaspora Councils, in 1938 and 1974, the possibilities and aims of youth work were dealt with in detail. In 1938, Archpriest P. Belovidov and Hegumen Philip (von Gardner) spoke on religious instruction for children and the importance of a Church school system. [5] Deyaniya vtorogo sobora, pp. 209-236. They indicated that the foundation of the Christian life must be laid in childhood. One must use all available interests in religion in each child, in order to create the foundations for Christian life. Here, above all, work must be done with the parents, who in turn can help the children by their example in the Faith. The family should be a “house church” of education; the Church and the parishes must strengthen the Faith through pre-school upbringing. Besides catechismal instruction, the children must also be given instruction in Church history. The history of the Orthodox Churches and the Russian Church should be the focal point. The clergy were required to especially concern themselves with youth work, and also the older adolescents and students, who are at a particularly critical age, should be more firmly integrated into parish life. Through religious discussions, youth circles, participation in patriotic assemblies, pilgrimages, and lectures, they should try to awaken the youth’s interest in the Church and to establish ties with the community. In connection with this, they particularly pointed to group work, to which one should draw as many young people as possible. [6] Ibid., pp. 54-56.

They cited as an example the St. Seraphim of Sarov Circle, which had existed in Belgrade since 1921. This Circle [7] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 130-138. met for religious discussions and was under the guidance of Metropolitan Anthony. Men and women belonged to it, as well as youth groups. One can measure the influence this circle had upon the participants by noting that, out of this Circle came five bishops (including Archbishop Nicodemus of Richmond & Great Britain), seven clergymen, and many nuns, including the late Abbess Magdalena (Countess N. P. Grabbe) and the iconographer-nun, Mother Flaviana (E. N. Vorobeva). [8] Ibid., p. 135. Speech by Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov) at the Third All Diaspora Council in 1974 (Synodal Archives, file 2/72).

A brotherhood that was formed after the Second All-Diaspora Council and still exists today is the St. Vladimir Brotherhood (Bratstvo Svyatoi Khristovoi Rusi imeni sv. kn. Vladimira). It was formed on the occasion of the 950th anniversary of the Christianization of Russia, which was celebrated in 1938. Members could be anyone over 18 years of age. They vowed to live according to the rules of the Church, i.e. by regularly attending the Sunday services, saying daily prayers, reading the Gospels in the family unit, and keeping the Church fasts, and so forth. The members were supposed to swear to establish and support organizations at all cathedrals, missions, and larger communities and to form youth groups for the young people. [9] Deyaniya vtorogo sobora, pp. 39-50; Shchukin, pp. 102-105.

At the third Pan-Diaspora Council, youth and group work took on broader proportions in the discussions. Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov) read a report on “Church Youth Work in the Diaspora”; Bishop Nectarius (Kontsevich) of Seattle spoke on the “Extracurricular Religious and Moral Upbringing of the Youth.” [10] Prav. Put’ (1974), pp. 3-26. In addition to this there were lectures and reports from the leaders of five Russian youth groups in exile on the following day. Archbishop Anthony (Medvedev) reported on the Church school system, and G. Lukianov, inspector of Church schools in Eastern America, gave a survey on the activities of Church schools of that diocese. [11] Prav. Rus’ (1947) 17, pp. 10-11; (1948) 4, pp. 10-11; 7, pp. 8-10.

In the resolutions, the “fundamental importance of the Church schools abroad” for the preservation of Orthodoxy and Russian culture among the growing youth was stressed. The Council called for all parishes and Church workers to give schooling and youth work more attention, and to establish new schools. It required the clergy to give regular religious instruction in their parishes and, when possible, to introduce a comprehensive study on general subjects such as language, literature, history, and so forth. As much as possible, the instruction at the parish schools should take place at least once per week, as a supplement to school attendance at the local schools. For information and advice in building up the parish schools, as well as for better coordination of the work within the individual dioceses, the Synod of Bishops Department for Academics & Education was established. [12]In Munich there were originally 3 Russian high schools. On account of the emigration overseas, two were closed; the third remained in existence until the mid-1950s when it too was closed. Prav. … Continue reading It was mandated to organize youth camps, extracurricular upbringing modeled on the example of the summer camp in the Chicago Diocese, which had existed since the 1960s, which Archbishop Seraphim had established, and which has since been emulated in many dioceses. [13] Der christlichen Osten (1963) 1, p. 27.

The largest youth group, with branches in all countries of the free world, is the Russian Scouts (Nationalnaya Organizatsia Russkikh Skautov) and the Russian Orthodox Youth Outside of Russia (Russkaya Pravoslavnaya Molodezh Za Rubezhom). The number of its members today is not known. In 1952, 18,000 youth belonged to the Scout Movement. [14] Prav. Rus’ (1952) 4, pp. 4-7. All youth groups met in congresses at specific intervals of time; at these congresses, they reported on their work.

The Third Pan-Diaspora Russian Congress of Orthodox Youth took place in Toronto, in 1978. Several hundred young people participated. At Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, the St. Herman Youth met in December of 1980 for their third session since 1973. This youth group has conducted research into the life of St. Herman [of Alaska]. At the session, 200 young people from North America participated. [15] Ibid. (1981) 1, p. 14. In recent years, there has been an annual youth pilgrimage to Jordanville for St. Herman’s Day, and a youth conference.

The greatest significance of the schools in the early years of the emigration — and this applies to both waves of emigration — lies in the fact that the youth were offered the opportunity to complete the schooling that was begun in their homeland. This often began in the displaced persons camps, where former teachers and students continued this schooling. One example that can, however, represent the others took place in 1945, in the Parsch Camp, near Salzburg, where a camp high school was founded, which was attended by 350 children. Of them, in the first year of its existence, 100 students received their diplomas, twenty of whom continued their studies on the college level. [16] “Proshchai Parsch” in Russky national’ny kalendar’ [Munich] (1951) p. 131. These camp schools were in many ways the new beginning of the school system. The Church was the only institution in position, during the early year, to take over the education of the youth when the children had not yet mastered the language of the host country. There was, moreover, also a lament that the youth of the second emigration displayed little inclination to preserve their Russianness in the emigration and were concerned with their own assimilation. The reason for this was, for example, the negative experience of Stalinism and the desire to make a new beginning. There were warnings against the dangers of a denationalization. The priests were called upon to strengthen their work with the youth and the education of the youth, and were told not to “shut themselves up in their churches,” but rather to “go into the families” and to intensify youth work. [17] Prav. Rus’ (1947) 17, pp. 10-11. Most dioceses had a pedagogical committee that aimed to set up Russian Church schools to cultivate the Russian language and culture and the deepening of religious upbringing. [18] Tserkovniya Vedomosti (Munich) (1952) 3-4, p. 20. This schooling extended from kindergarten to preparatory classes with reading courses, from elementary to secondary schools. The latter also were located in the large cities with numerically strong communities and in refugee camps. In the mid-1950s, most of these schools suspended their work. [19] Seide, Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in BRD, p. 169.

Today there are still some 100 parish schools; these may be divided into three separate categories: kindergartens and parish schools from the larger communities. The number of students reaches from 2-5 children to groups of 20 children; the number of classes, including the preparatory and reading classes, consists of up to ten grade levels. [20] Andreev, “O vospitanii detei.” In addition to these elementary schools, the Church Abroad has two high schools, in New York and San Francisco respectively, whose diplomas are equivalent to that of the public high schools. Two boarding schools are maintained by nuns in Bethany and Santiago. Both general subjects and religious subjects such as biblical history, the lives of the saints, catechism, ecclesiastical chant and Church history are taught. The general subjects primarily include Russian language, grammar and literature, and additionally Russian history, geography and music. At the larger schools this was supplemented by theater, dance, and instrumental groups and choirs. At these schools, there are libraries with special literature for children and adolescents. Most students celebrate the end of the school year together with their parents, sometimes by theater productions and musical presentations. At Christmas, the children become better acquainted with Russian Christmas customs.

The largest parish schools in existence today are in the United States. Most of them were founded in the 1950s, but new schools were added in the 1960s and 1970s. One of the largest schools is at the Holy Transfiguration Cathedral in Los Angeles, which is attended by 250 children and has 12 classes, which reach from the pre-school (3 classes) to the main school (9 classes). For the younger students, the school has its own school bus, which collects children from the suburbs and the city. There was a large school with 130-150 children at the Archangel Michael Church in Paterson. This school was founded in 1952 and is attended by 35 pupils; the number grew in subsequent years to reach its present-day level. Besides these, there are also large schools in Lakewood, Nyack, Washington D.C., and other cities, which are attended by 50-70 children. [21] Prav. Rus’ (1960) 15, p. 8; (1964) 16, pp. 10-11; (1965) 1, pp. 9-10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 764, 824, 879, 1366, 1411, 1420.

The most important full-time parochial schools are the Synod’s St. Sergius of Radonezh High School in New York and St. Cyril High School in San Francisco. The Synodal school in New York was founded in 1953 and at first located in the House of Free Russia. In the first years of its existence, instruction took place only on a weekly basis. The number of students in these years was between 120 and 150. In 1959, the school was transferred to the Synod building on Park Avenue and began giving daily instruction. Eighteen to twenty teachers taught some 140-160 children in twelve classes. The school had its own 10,000 volume library and a small printing press, in which school books and other teaching materials were printed. In addition to Russian subjects, which were taught in Russian, there was also instruction in English, because the curriculum was equivalent to that in American public schools. The school was accredited by the state as a high school. The school’s annual budget is around $120,000. [22] Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 477-481; Prav. Rus’ (1962) 7, pp. 8-9; (1969) 20, p. 12. A second high school is located in San Francisco and attended by 250 students. The school was founded in 1950 and began its educational work with 70 students. It had been preceded by a parish school founded in 1943. When the Russian parishes in the city grew after World War II, the school was turned into a high school. Today there are still reading classes for the youngest children, three preparatory classes, and seven secondary level classes. Some 15 teachers give instruction. Also, here Russian subjects, such as Russian language, grammar, literature, history, geography, economics, and, of course, religious instruction, are the focal points. These are, as in New York, supplemented by other subjects such as English language and literature, American history and geography. Scientific subjects were taught in Russian. [23] Prav. Rus’ (1951) 1, pp. 10-11; (1962) 6, pp. 9-10.

In addition to the schools in the U.S. dioceses, there are also schools in the Canadian diocese (8 schools, the largest of which is in Toronto, with approximately 100 children) and in the Australian diocese (6 schools). The largest Australian school is located in Brisbane, with 10 classes and 150 students, and a 1,000 volume school library. In South America, there are larger schools in Argentina and Brazil, which on the average are attended by 30-70 students.

The Russian community in Tehran founded its own school in 1962/63, when the parish experienced a revival under the direction of Archimandrite Victorin. In the first academic year, 80 children attended; there were 5 teachers and a 1,200 volume library. [24] Prav. Rus’ (1963) 20, p. 11; (1964) 4, pp. 9-10.

Similarly, in Europe there are parish schools in the larger communities. The most important school is doubtless St. Vladimir School in Brussels, which has its own school building and is attended by some 60-70 children, also including Serbian Orthodox children. In the German Diocese, there are about a dozen smaller parish schools. By 1967, 4,000 children had attended these schools. In Bavaria, classes in Orthodox religious instruction were held, in which there were a minimum of 15 Orthodox children. The Ministry of Cults paid the teachers. The larger schools were attended by 20-30 students. Smaller parish schools also existed in Austria, Switzerland, France, Luxemburg, and Great Britain. The London Saturday school was founded in 1954, when the nuns who fled from Palestine under the direction of Abbess Elizabeth (Ampenov) arrived in London and established the Convent of the Annunciation. In the first years of its existence, a total of 84 children attended the school. [25] Prav. Rus’ (1960) 15, p. 8; (1964) 16, pp. 10-11; (1965) 1, pp. 9-10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 879, 1018, 1059.

Both the school run by the nuns in Bethany and the one run by the nuns in Santiago hold a special position within the school system. Besides the school, they also have a boarding house and an orphanage.

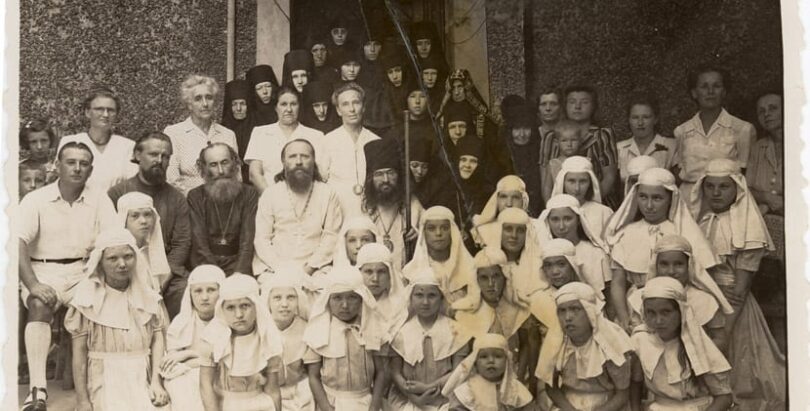

In Bethany, a school for girls with a boarding house was founded in 1934, upon the initiative of Mother Mary (Stella Robinson), later the Abbess of the Ascension Convent [on the Mount of Olives], and her coworker, Sister Martha (Alexandra Sprot). The former was Scottish and the latter English; both converted to Orthodoxy in the early 1930s. While Mother Mary took over the direction of the newly-founded convent, Mother Martha headed the school. The school received recognition from the English High Commissioner as an English college and thus the right to grant diplomas, qualifying the recipient to continue his studies on the college level. With this school, the Church Abroad was continuing the tradition of the pre-Revolutionary Russian Church. Even to the present day, it is the only Orthodox school for Arab girls in the Holy Land.

The school is attended by 140 Arab girls, from 6-16 years of age, of which half lived in the boarding house attached to the school. In the first years of its existence, the school was attended by 20-30 children, whose number, however, grew remarkably. The children who board there are in part orphans, in part children of refugees who fled from the Israeli section during the partition of Palestine. Time and again, some of the children from the boarding house and school enter the three convents.

Instruction is given daily between 8 A.M. and 3 P.M. and corresponds to the curriculum in Jordanian schools. There are ten salaried teachers, and an additional three from the convent. The latter teach religion, Church singing, and, for several older students, icon painting. There are a total of 9 classes, 6 on the elementary level and 3 on an advanced level. In addition to the material covered in Jordanian schools, the girls also receive instruction in religion, home economics, and three languages: Russian, English, and Arabic. Additional subjects are icon painting and Church singing, in which four languages are used: Church Slavonic, Greek, Arabic and English. The school receives a monthly stipend of $1,600 from various funds of the Church Abroad. For students without means, there is a scholarship. [26] Prav. Rus’ (1952) 24, pp. 4-7; (1965) 5, pp. 8-9; (1977) 20, pp. 13-14; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 447-460. Along the lines of the tradition in Palestine is a school run by four nuns under the direction of Mother Juliana in Santiago, Chile, where they live in a convent dedicated to the Dormition of the Theotokos. The nuns came from the Ein Karim Convent which is located in the Israeli part of Palestine; the nuns left it after it was handed over to the Moscow Patriarchate. The orphanage and convent school were founded in 1966. With the financial support of the Church Abroad and the Chilean authorities, the undertaking was realized. In 1969, studies began, and the first 14 orphans came to live in the orphanage. By 1972, the number grew to 40 girls of all ages. Those older than 6 years of age attended the school which, by 1977, 186 children had attended. For most children, there is no tuition, because they are from poor Chilean families. Many children also receive a free breakfast. The school’s curriculum corresponds to that of Chilean elementary school. Children also receive Orthodox religious instruction and instruction in the Russian language, history, and church singing. The orphans are all baptized into the Orthodox Faith and speak good Russian, which is an elective subject for the Chilean children.

The school is dependent upon the financial support of the Synod of Bishops and the Chilean authorities, because the convent only has revenues from a small garden, which is not enough to support the school and the orphanage. [27] Prav. Rus’ (1972) 10, pp. 9-10; Abbess Juliana, “Pis’mo iz Chile,” in Pravoslavnoe obozrenie [Montreal] (1979) 47, pp. 63-68; “Orthodox Life” (1982) 4, pp. 35-38.

Both of these schools play a special role in helping the Russian Church Abroad to carry on an old tradition from pre-Revolutionary times: instruction and mission for Orthodox minorities, such as in Palestine or for non-Orthodox orphans. The success of these efforts is not wanting. Some two-thirds of all nuns in the Church Abroad’s convents are of Arab extraction.

References

| ↵1 | In Russia after the Revolution, the entire educational system was revamped in accordance with the Marxist-atheist worldview. Some things representing the old culture were destroyed, others were damaged by intentional alienation and still, others were completely destroyed. Everything of ecclesiastical origin suffered the most. Classics of world literature were banned from the libraries or no longer published. The first edition of Dostoevsky’s collected works was only published in 1965 in the Soviet Union. The publication of this edition, begun at that time and later suspended, was still not complete at the time of the publication of this book. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | The Metropolia was the first to initiate the development of church Sunday schools, in which instruction was given in English and which concentrated on catechism. In 1953 there were 76 such Sunday schools; in 1961 there were 141. (Tarasar, pp. 234-239.) |

| ↵3 | Fr. Johannes Chrysostomus repeatedly prophesied the demise of the Church Abroad without ever having established this in full; compare his essays “Patriarch Tichon” and “Die Russisch-Orthodoxe Kirche.” |

| ↵4 | Seide, Jerusalemer Mission; Idem., Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in China. |

| ↵5 | Deyaniya vtorogo sobora, pp. 209-236. |

| ↵6 | Ibid., pp. 54-56. |

| ↵7 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 5, pp. 130-138. |

| ↵8 | Ibid., p. 135. Speech by Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov) at the Third All Diaspora Council in 1974 (Synodal Archives, file 2/72). |

| ↵9 | Deyaniya vtorogo sobora, pp. 39-50; Shchukin, pp. 102-105. |

| ↵10 | Prav. Put’ (1974), pp. 3-26. |

| ↵11 | Prav. Rus’ (1947) 17, pp. 10-11; (1948) 4, pp. 10-11; 7, pp. 8-10. |

| ↵12 | In Munich there were originally 3 Russian high schools. On account of the emigration overseas, two were closed; the third remained in existence until the mid-1950s when it too was closed. Prav. Rus’ (1952) 5, pp. 15-16. |

| ↵13 | Der christlichen Osten (1963) 1, p. 27. |

| ↵14 | Prav. Rus’ (1952) 4, pp. 4-7. |

| ↵15 | Ibid. (1981) 1, p. 14. |

| ↵16 | “Proshchai Parsch” in Russky national’ny kalendar’ [Munich] (1951) p. 131. |

| ↵17 | Prav. Rus’ (1947) 17, pp. 10-11. |

| ↵18 | Tserkovniya Vedomosti (Munich) (1952) 3-4, p. 20. |

| ↵19 | Seide, Russisch Orthodoxe Kirche in BRD, p. 169. |

| ↵20 | Andreev, “O vospitanii detei.” |

| ↵21 | Prav. Rus’ (1960) 15, p. 8; (1964) 16, pp. 10-11; (1965) 1, pp. 9-10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 764, 824, 879, 1366, 1411, 1420. |

| ↵22 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 477-481; Prav. Rus’ (1962) 7, pp. 8-9; (1969) 20, p. 12. |

| ↵23 | Prav. Rus’ (1951) 1, pp. 10-11; (1962) 6, pp. 9-10. |

| ↵24 | Prav. Rus’ (1963) 20, p. 11; (1964) 4, pp. 9-10. |

| ↵25 | Prav. Rus’ (1960) 15, p. 8; (1964) 16, pp. 10-11; (1965) 1, pp. 9-10; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 879, 1018, 1059. |

| ↵26 | Prav. Rus’ (1952) 24, pp. 4-7; (1965) 5, pp. 8-9; (1977) 20, pp. 13-14; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 447-460. |

| ↵27 | Prav. Rus’ (1972) 10, pp. 9-10; Abbess Juliana, “Pis’mo iz Chile,” in Pravoslavnoe obozrenie [Montreal] (1979) 47, pp. 63-68; “Orthodox Life” (1982) 4, pp. 35-38. |