Part IV, Chapter 1.4

The Dioceses in the U.S.A.

From 1945, the center of church life was transferred overseas because the mass of refugees since 1948/49 had emigrated, especially to the U.S.A. and Canada. Half of all the communities of the Church Abroad today are situated in the U.S.A. and Canada, where the only seminary and numerous monasteries, printing presses, and special church institutions are to be found. The most numerically significant communities are located in Eastern America, California, and the Canadian province of Québec. Over half of all the faithful live today in the U.S.A. and Canada.

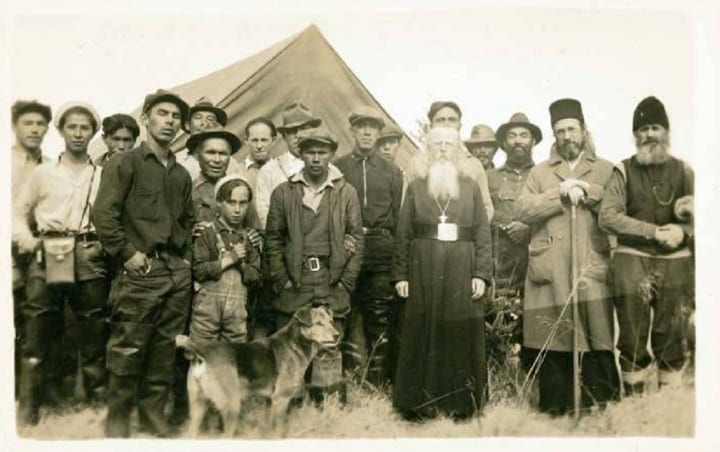

The Orthodox in North America can look back upon a two-hundred-year history. [1] On the development in North America, cf. Part I, Chap. 4. In the autumn of 1794, eight Russian monks from the monasteries on the islands of Valaam and Konevets set landed at Kodiak Island in the Gulf of Alaska. One of these monks, Herman, was glorified as a saint in 1970. The small group was supposed to establish an Orthodox Mission among the inhabitants of the Aleutians. Within only two years, twelve thousand people had converted to Orthodoxy. [2] Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 15; Besin, The Orthodox Church in Alaska.

In 1799, the Holy Synod resolved to create a diocese of Kamchatka and North America, and assigned the direction thereof to Archimandrite Joasaph (Bolotov), who was already in charge of the Mission. Archimandrite Joasaph returned to Russia and was consecrated bishop, but on the return, journey lost his life in a shipwreck. No successor was named. [3] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 4. It took forty years for the Mission to recover from this setback. In 1838, there were 10,313 faithful, thus less than forty years earlier. [4] Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 17; Ushimaru, Bishop Innocent. In 1840, the Mission took a turn for the better, when the widowed priest John Veniaminov was consecrated Bishop Innocent of Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands, and the Aleutians. Fr. John, together with his family, had come to the island of Unalaska from Siberia in 1824. After a three-year stay in Petersburg (1836-39), he succeeded in convincing the ecclesiastical and civil authorities that with sufficient personnel and material support the Mission on the American continent would have a bright future.

Bishop Innocent (the Patriarchal Church glorified him as a saint in 1978) returned to Sitka (Novoarchangelsk) in September of 1841, where he began to build up the Mission. A theological school was founded, which was transformed into a Theological Seminary in 1844. The number of clergy and missionaries increased, and the education of native priests began. The Mission energetically undertook the task of evangelization among the inhabitants of Alaska and the Kuril and Aleutian Islands. In 1850, Bishop Innocent, “the Apostle of Alaska”, was elevated to the rank of archbishop for his labors, and this diocese was expanded to include the huge territory of Yakutia, in Siberia. In 1853, the episcopal see of Sitka was transferred first to Yakutsk, and then, four years later, to Blagoveshchensk. For the former diocese of Alaska, a vicar bishop, Bishop Peter (Sysakov), was appointed in 1857; the episcopal residence was in Sitka. [5] Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 17-18; Severnoi Ameriki, p. 3.

In 1870, the vicariate was erected as the independent Diocese of the Aleutians & Alaska, and the episcopal residence was transferred to San Francisco, where numerous Orthodox faithful resided. In this manner, the first diocese of the Russian Church on the North American continent came into existence. Bishop John (Metropolsky), who resided in San Francisco after 1872, took over the direction of the diocese. His successors were the following bishops: Nestor (Zakkis, 1879-82; 1882-88 ruled the Diocese of St. Petersburg), Vladimir (Sokolovsky, 1888-91), Nicholas (Ziorov, 1891-98), Tikhon (Bellavin, 1898-1907), Platon (Rozhdestvensky, 1907-14), Eudocius (Meshchersky, 1915-17), and Alexander (Nemolovsky, 1914, 1917-21). [6] Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 20-28, 121. After 1870, the jurisdiction of the bishop in practice comprised all of North America. Bishop Vladimir was recognized as the canonical authority by all the Orthodox who lived in the country; [7] Ibid., p. 21. at this time, he was the only Orthodox bishop in North America. Under his successor, Bishop Nicholas, numerous Uniate communities (mostly Carpatho-Russian faithful) reunited with the Russian Orthodox Church. This led to a fundamental strengthening of Orthodoxy in the country.

The Russian Orthodox Church’s jurisdiction over the Orthodox in America was confirmed in 1895 by the resolution of the Holy Synod to establish a Syro-Arabic Mission there for the Syrian Orthodox Christians, which was subject to the Russian Church (not to the Patriarch of Antioch). The latter recognized this. [8] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 4. Under Bishop Tikhon (Bellavin, later Patriarch), Orthodoxy experienced a further upswing. In 1900, the diocese was renamed the Diocese of Alaska & North America; in 1904, two vicariates were created. The Syrian Archimandrite Rafael (Hawaweeny) was appointed Bishop of Brooklyn for the Syrian-Arab Christians. Innocent (Pustinsky) was appointed vicar bishop for Alaska. All three bishops were subject to the Holy Synod in Moscow. In the following year (1905), the episcopal see of San Francisco was moved to New York, where the Cathedral of St. Nicholas on East 97th Street, was completed. Also, a theological seminary was founded in Minneapolis, which was to educate priests who were born in the country. In Canada, a mission was founded, which was to take over the care of the Orthodox communities there. [9] Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 24-25. Archimandrite Alexander (Nemolovsky) assumed the direction of the Canadian Mission in the years 1905-1909. Also, the first Orthodox monastery was founded, in 190,5 in South Canaan (Pennsylvania): St. Tikhon’s, whose first abbot was Hieromonk Arsenius (Chagovtsev; from 1926 Bishop of Winnepeg). [10]St. Tikhon’s Monastery is generally accepted as the first Orthodox monastery in North America, although this is not exactly correct because St. Herman had founded a skete called New Valaam in the … Continue reading In 1907, another noteworthy event in the life of North American Orthodoxy was the meeting of the first Local Council of the “Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of North America, under the direction of the Russian Church,” in Mayfield, Pennsylvania. Bishops Tikhon, Rafael and Innocent, and representatives of the clergy and laity, took part.

The Orthodox communities of Greeks and Serbs in the U.S., which were headed by archimandrites, recognized the jurisdiction of the Russian Church. When Bishop Platon succeeded Bishop Tikhon, in 1907, he was greeted by representatives of the Greek and Serbian communities. Bishop Rafael delivered the welcoming speech, in which he among other things said:

“Out of the little acorn of the Orthodox Ecclesiastical Mission and the Aleutian Diocese has grown the mighty oak of the North American Diocese, with two vicar bishops – of the Aleuts (for the inhabitants of the Aleutians and the islands of Alaska) and of Brooklyn for the Syrian-Arabs – and the heads of other Orthodox missions: the Greek Archimandrite Theocletos of Galveston, the Serbian Archimandrite Sebastian for the Serbs, and the American priest Nathaniel for Americans, with five journals – in Russian, Arabic, Serbian, English and Ukrainian. [11] This refers to the Ukrainian language. Also in the North American Diocese there are two seminaries (in Minneapolis and Sitka), two theological schools (in Cleveland and Unalaska), an orphanage, a monastery, many Sunday schools and cemeteries, and more than a hundred communities, of which the majority have their own churches, the most notable of which is this wonderful cathedral. [12]The address was delivered in St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York. Today this cathedral belongs to the Moscow Patriarchate after it had been in the hands of the Renovationist “Metropolitan” … Continue reading The Church has one hundred priests, at whose head Your Eminence stands.” [13] Seraphim, Church Unity.

The number of 100 communities was arrived at, because the communities in Canada, the Aleutians, Alaska and so forth were included. Actually, the diocese had 72 communities in 1914; at the time of Archbishop Platon’s departure, though the number grew to 137. [14] Ibid., pp. 27-28.

The vicariates were ruled as follows: Bishop Innocent (Pustinsky) ruled the Alaskan Diocese from 1904 to 1909, and Bishop Alexander (Nemolovsky) from 1909 to 1916. He was appointed administrator of the North American Diocese, in 1914, because Bishop Eudocimus (Meshchersky), as a result of wartime events, only arrived in North America in 1915. From 1916-21, Philip (Stavitsky) was Bishop of Alaska. The Vicariate of Brooklyn, for the Syro-Arabs, was headed, first by Bishop Rafael from 1904-1915, and then remained vacant for two years; from 1917-33, Bishop Euthymius headed it. Bishop Alexander was transferred to the Canadian Mission, which had been in existence since 1906; in 1916, he was appointed Bishop of Canada, with this see in Winnipeg. In practice, however, he did not assume this position because Bishop Eudocimus [15] Bishop Eudocimius did not return to the USA. He joined the Renovationists in 1923. had to travel to the Pan-Russia Council in Moscow. Thus, Bishop Alexander served as the head of the North American Diocese until 1921. When it was certain that Bishop Eudocimus would not return to the U.S.A., Bishop Alexander was elected Bishop of America & Canada in 1919 by a diocesan assembly. [16] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 7.

For the Carpatho-Russian faithful, yet another bishop was consecrated in 1917. After Archpriest Alexander Dzubai returned to Orthodoxy from the Unia, and was consecrated Bishop Stephen of Pittsburgh. The hope that he would succeed in bringing more Uniate communities back to Orthodoxy were not fulfilled, however. He himself returned to the Unia in 1924 and was succeeded by Bishop Adam (Philippovsky).

The Supreme Ecclesiastical Administration (SEA) recognized the 1919 election of Alexander as bishop. The SEA granted Bishop Alexander competence over church divorce, thereby recognizing him as ruling bishop of the diocese. [17] Tserk. Ved. (1922) 4, p. 10. The jurisdictional competence of the SEA over North America seems not to have been challenged. Thus, the Vicariate of the Aleutians & Alaska was elevated to a ruling diocese, against which Bishop Alexander protested in vain. [18] D´Herbigny/Deubner, Evêques russes, p. 93. The rule of the new diocese was transferred to Archimandrite Anthony (Dashkevich; from 1918 the rector of the Copenhagen parish), who, however, was unable to assume his responsibilities due to ill health.

In April of 1921, Metropolitan Platon was instructed by the SEA to undertake a visitation to the U.S.A., where churches were being mortgaged and church property was being sold after financial support from Russia had ceased and stipends for priests and missionaries were no longer being received. [19] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 383-385. Metropolitan Platon made this trip at the directive of the SEA. Who named Metropolitan Platon ruling bishop in North America is contested.

In June of 1922, Archbishop Alexander resigned the rule of the North American Diocese in a letter to Metropolitan Platon. He simultaneously requested that the Metropolitan take over the direction of diocese. Platon agreed, on 3 July 1922, providing that he would not be held responsible for all financial debts from the preceding time. In this manner, Platon inherited the administration of the diocese from Archbishop Alexander, who left America and retired to the Russian Skete of St. Elias, [on Mount Athos].

As previously mentioned, in May of 1922, Mr. Kolton, the president of the YMCA in the U.S.A., and Archpriest Theodore Pashkovsky (later Metropolitan Theophilus), visited Patriarch Tikhon. During this conversation, the Patriarch expressed the wish to transfer the rule of the North American communities to Metropolitan Platon. Kolton conveyed this wish of the Patriarch to the “Provisional Synod of Bishops” in July of 1922. On this basis, the Synod appointed Metropolitan Platon provisional leader of North America. [20] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 7. The letter should have reached Metropolitan Platon after the retirement of Archbishop Alexander. Platon’s appointment by the Church Abroad was based on an oral directive from Patriarch Tikhon, upon which the Synod in its correspondence also reported expressly. Platon, however, wanted a direct written confirmation from the Patriarch, in order for no doubt to be left as to his appointment. He received this confirmation in September of 1923, again via the Synod of Bishops to whom the Patriarch had addressed himself. In this decree, the Patriarch decreed that Metropolitan Platon should be appointed ruling bishop of the North American Diocese, and Archpriest Theodore Pashkovsky should be consecrated Bishop of Chicago. A copy of the decree was forwarded to Metropolitan Platon and was simultaneously published in Church News. [21] Ibid., p. 384.

The appointment of Platon was accomplished by the Patriarch and the Holy Synod in April of 1922, and was finally confirmed in September of 1923. Platon assumed his office on the basis of an oral communiqué from the Synod, which, in turn, appointed him. The fact that Patriarch Tikhon sent his decree to the Synod in Karlovtsy, instead of directly to Platon, indicated that the Patriarch himself recognized the Synod’s competence over the emigration and, furthermore, as the only de jure central ecclesiastical governing body for the emigration.

Patriarch Tikhon’s confirmation of September 1923 did not change the de facto situation that had been in effect since July of 1922. Platon must have viewed the appointment by the Synod of Bishop as valid, because, in November of 1922, at the Pan-America Church Council, he allowed them to elect him First Hierarch of the North American Diocese and assumed the title of “Metropolitan of All America & Canada.” [22] Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 30.

The influx of Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe, Southern Europe, and Turkey after 1920 led to the establishment of many new communities. In 1924, there were already over 300 communities in the U.S.A. and Canada. [23] Ibid., p. 31. To better care for these communities, new bishops were sent in the course of subsequent years. In 1922, Archpriest Theodore Pashkovsky was consecrated Bishop of Chicago, with the name Theophilus. The Alaskan missionary and administrator of the Canadian communities, Archimandrite Amphilocius, who served there for many years, was consecrated Bishop of Alaska. Archimandrite Adam (Philippovsky) assumed the direction of the Canadian communities; he was consecrated by Bishops Stephen (Dzubai) and Gorazd (Pavlik), in 1922. [24] Bishop Adam was a native Carpatho-Russian, was converted to Orthodoxy by Bishop Gorazd (Pavlik), rector of the small Czech Orthodox Church in Prague, and was ordained by Bishop Stephen. In 1924, Adam succeeded Bishop Stephen, who relapsed to the Unia. The former also took over the direction of the Carpatho-Russian communities. At the request of Metropolitan Platon, Bishop Apollinarius (Koshevoi) came to America in 1924 and became the Bishop of Winnipeg. In the same year, he was transferred to San Francisco, where he made the old 19th-century cathedral – the Cathedral of the Joy of All Who Sorrow – his cathedral. [25] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 269-272. He was the only hierarch who did not join the schism of 1926, thereby saving the position of the Church Abroad in North America. Bishop Arsenius (Chagovtsev, the founder of St. Tikhon’s Monastery, had been consecrated Bishop of Winnipeg in Belgrade, upon the request of Metropolitan Platon. A few weeks after his consecration, the schism occurred. Bishop Arsenius joined Metropolitan Platon. [26] Ibid., 5, p. 272.

The following hierarchs belonged to the Church Abroad in North America before the schism in 1926: Metropolitan Platon of All America & Canada (ruling bishop of the diocese), Archbishop (since 1923) Euthymius of Brooklyn for the Syrian-Arabs, and Bishops Theophilus of Chicago, Amphilocius of Alaska, Apollinarius of San Francisco, Arsenius of Canada, and Adam of Philadelphia. However, the Synod had imposed a ban on the celebration of the Holy Mysteries by Bishop Adam. [27] Tserk. Ved. (1926) 17-18, p. 4. After the schism, Metropolitan Platon restored him again to his office.

A significant event in church development in North America, as well as in the Church Abroad, was the Detroit Council of 1924. [28] Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 9-16; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 385-386; Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 30-31. Present at this Council were Metropolitan Platon and Bishops Stephen, Theophilus, and Apollinarius, as well as representatives from 111 communities, about half of all the communities in North America. Despite the presence of four bishops, including the ruling bishop in North America, none of the hierarchs presided over the assembly. On the ground of this violation against church order, as well as the fact that only about half of all the communities were represented, the canonical character of the Council was contested from the beginning.

At this Council, it was decided that the Orthodox communities of North America should administer themselves in the future. A constitution for an “American Orthodox Church” was supposed to be written, which would create a quasi-autocephalous status. One hundred and eleven communities agreed to these resolutions, which were initiated by the majority of the laity and several representatives of the clergy, including Archpriest Leonid Turkevich (later Metropolitan Leontius). Another 42 communities agreed to these resolutions in the weeks after the Council; 12 Canadian communities also agreed to the project at an assembly in the summer of 1924. Altogether, 164 of some 220 communities voted for separation from the Church Abroad.

Metropolitan Platon could not have disregarded the result of this vote, when he traveled to Karlovtsy, in 1926, as a participant in the Council of Bishops. His position was additionally weakened because he had been accused. as “leader of the North American Diocese”, of counterrevolutionary acts against the Soviet regime, in an alleged decree, dated 16 January 1924, by Patriarch Tikhon, which was also signed by Archbishops Seraphim and Peter. [29]This alleged decree of Patriarch Tikhon was published in Seraphim’s Church Unity“, p. 126. It was either presented to the Patriarch just for his signature or completely falsified in order to … Continue reading The fact that Metropolitan Platon had not desired a break in 1926 is significant, but in view of the behavior of his communities in North America, he used Metropolitan Eulogius’ differences of opinion with the Synod to blame the schism on the Synod. At this point, the course of the 1926 Council must once again be studied. The differences of opinion at the Council certainly did not justify a break, but rather the further developments of subsequent weeks resulted in the fateful church schism. [30] Cf. Part I, Chap. 4.

Metropolitan Platon disputed the Synod’s jurisdiction over the communities in North America and called the Synod uncanonical. [31]Severnoi Ameriki, p. 28. Cf. on the ecclesiastical schism in North America, the work of Lebedev, Razrukha, which was published in Belgrade in 1929 and comprised the first detailed description of the … Continue reading Metropolitan Platon’s explanation was hardly convincing. Since the evacuation, he had participated in all the important resolutions of the SEA, the Synod of Bishops, and the Council of Bishops. While journeying to Constantinople, he had endorsed the document that declared the SEA’s competence over the refugees in all countries where normal relations with the Patriarch were not possible. [32] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 6-7. He allowed himself to be appointed by the SEA as a cleric for the Athens embassy church, in November 1920. In January of 1921, he allowed himself to be sent to America to bring order to the affairs of the Church there. And finally, he obtained the Synod’s provisional appointment as ruling bishop in North America. [33] Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 23-26. He took part in the Karlovtsy Council in 1921, and at the sessions of the Synod of Bishops until 1926. Not unjustly was he was considered to be a co-founder of the Church Abroad. [34] Ibid., p. 23.

The “Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic & Apostolic Church in North America,” which Metropolitan Platon originated, was not recognized by any Orthodox Church [35] Ibid., pp. 36-39; Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 32-44; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 396-398. and was, until the reunification with the Church Abroad in 1936, completely isolated. The “Metropolia” had 250 communities during these years. After the break in 1926, it kept about 90% of all the faithful, and all the hierarchs, except Bishop Apollinarius, had joined the schism.

The Synod of Bishops responded to the break by deposing Metropolitan Platon as head of the North American Diocese and by imposing a ban on the celebration of the Holy Mysteries.

The Synod appointed Bishop Apollinarius as a provisional head. [36] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 7:390-391. In two epistles, the Synod notified the faithful that it had deposed Metropolitan Platon and the other hierarchs and banned them from celebrating the Mysteries. [37] Ibid., pp. 392-396. Bishop Alexander (Nemolovsky), who was still living on Athos, was instructed by the Synod to return to his diocese in North America and take over its direction. Because he did not heed this demand, he was put on ecclesiastical trial and relieved of his post. [38]Tserk. Ved. (1928) 5-6, p. 1. In 1924 the Synod ordered him to return to his diocese of Alaska. When he did not follow this order, he was deposed as Bishop of Alaska. In 1928 he joined Metropolitan … Continue reading Bishop Apollinarius was appointed in his stead. In 1929, the latter was elevated to the rank of archbishop. From 1929 until his death in 1933, he ruled over the North American communities with the title of Archbishop of North America and Canada. To provide support for him, three vicariates were created: in 1930, Archimandrite Tikhon was consecrated Bishop of San Francisco; [39]Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 276-278. After the 1926 schism, Metropolitan Platon deposed Bishop Apollinarius as head of the San Francisco Diocese and replaced him with Archimandrite Alexis … Continue reading a few months later, Archimandrite Joasaph was consecrated Bishop of Montréal; [40] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 278-280. and in January of 1931, Archimandrite Theodosius was consecrated Bishop of Detroit. [41] Ibid., pp. 280-282. Bishop Theodosius was then entrusted with the rule of the newly-created Diocese of São Paulo & Brazil. Archimandrite Vitalis was consecrated Bishop of Detroit, but in the same year was given the leadership of the North American Diocese. [42] Vitalis, Motivy moei zhizni. Archimandrite Hieronymus became Bishop of Detroit in the following year.

After the death of Bishop Apollinarius, in 1933, Bishop Tikhon became a provisional leader in North America. He held this position from July of 1933 until September of 1934, finally as Archbishop. In September of 1934, Bishop Vitalis was appointed Archbishop and leader in North America & Canada. Simultaneously, two independent dioceses were created: Eastern America & (Eastern) Canada, with its see in New York, headed by Archbishop Vitalis, and Western America & San Francisco, headed by Archbishop Tikhon. The Diocese of Western America also included the Western Canadian communities and those in Alaska. At first, a vicar bishop resided in Canada, but later, at the end of 1934, the vicariate was turned into the independent Diocese of Edmonton & Canada. Thus, the Church Abroad, in 1935, shortly before the reunification, included the following dioceses: Eastern America & New York, Western America & San Francisco, and Edmonton & Canada.

In 1933, when Archbishop Apollinarius died, 62 communities belonged to these three dioceses, recognizing the jurisdiction of the Church Abroad. In 1935, there were already 80 communities. [43] Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 399; Severnoi Ameriki, p. 59. Considering that in 1927, 90% of the faithful had separated themselves from the Church Abroad, Archbishop Apollinarius achieved remarkable success, having over sixty communities, for he had begun with barely a dozen communities in Western America.

The most significant decision, the importance of which, however, was not foreseeable in 1930, was the blessing to found the Holy Trinity Monastery, in Jordanville. Hieromonk Panteleimon (Nizhnik) had joined the Church Abroad after the 1926 Schism and left St. Tikhon’s Monastery. He and a few co-workers had bought a plot of land in the late 1920s, in order to found a monastery. They received permission to do this from Archbishop Apollinarius, who was later to find his last resting place there in the monastery’s cemetery. His successor, Archbishop Vitalis, consecrated the small monastery church in 1934; he, however, is buried at the St. Vladimir Memorial Church [in Jackson, New Jersey]. Holy Trinity Monastery was the first monastery of the Church Abroad in America. In the course of its existence, it developed into the most important ecclesiastical and spiritual center of the Church Abroad and took the place of the Church Abroad’s monasteries in Eastern Europe and Manchuria. [44] Seide, Klöster im Ausland.

For the residence of the ruling bishop, Archbishop Apollinarius chose the Cathedral of the Elevation of the Cross in the Bronx, a borough of New York City. [45] Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, p. 520. This church remained the cathedral until 1940 when it was transferred to another building, consecrated as the Cathedral of the Ascension. The new cathedral remained Archbishop Vitalis’ church until his death in 1960. Thereafter, this building lost its significance, because, at the end of the 1950s, the new cathedral was consecrated at the headquarters of the Synod of Bishops. When racial unrest shook the Bronx in the mid-1960s, the old cathedral had to be closed.

In the Cathedral of the Ascension, important relics were preserved and venerated. In 1934, the Brotherhood of the Pochaev Monastery sent the parish a copy of the Wonder-working Pochaev Icon of the Theotokos. The Ladomirovo Monastery Brotherhood sent the community relics of St. Panteleimon, after Archbishop Vitalis, the [former] abbot of the Ladomirovo Monastery, made the church into his cathedral. The left wall of the church was adorned from 1947 with a very large icon of “All Saints of Russia” by Archimandrite Cyprian. [46] Cf. Part IV, Chap.7. This icon is today located in the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign, at Synod. The copy of the Pochaev Icon hangs in the winter Church of St. Job of Pochaev, in Jordanville. [47] Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 521-534.

The most important communities belonging to the Church Abroad in these years were as follows: in New York, the cathedral parish, the parishes of the Holy Fathers of the Seven Œcumenical Councils, and of the Holy Trinity; in Seattle, the parish of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker; in Detroit, the parish of the Dormition; and in Los Angeles, the Transfiguration parish. All these churches still exist today and serve as cathedrals. [48] Ibid., 1, pp. 535, 676, 743, 747; 2, pp. 769-770.

The administrative structure of the Church Abroad was only of short duration. It was barely completed when reunification with the schismatic Metropolia came about. Even before the death of Metropolitan Platon, a change was in evidence. In a letter in 1933, Metropolitan Platon declared himself in favor of “reconciliation” with the Synod, under the condition that he be allowed the right to maintain the title “Metropolitan of All America & Canada.” [49] Severnoi Ameriki, p. 52. This amounted to the fact that the Russian communities in North America, with their far-reaching autonomy in ordering their internal affairs, would recognize the Synod’s canonical competence and spiritual authority in deciding questions of the Faith, church order, and relations with other Churches – concessions that were also made during the negotiations of 1935. The work of reunification, however, was to fall to Metropolitan Theophilus.

After the restoration of Church unity, over 350 communities and half a million faithful belonged to the North American Metropolia. [50] Church News (1940) 7, pp. 47-51. This Church province, therefore, was the most numerically significant province of the Church Abroad. However, proportionally North America was greatly surpassed in spiritual and ecclesiastical splendor by the dioceses in Europe and the Far East, with their monasteries, printing presses, and seminaries.

From 1934, the rule of this large diocese fell to Metropolitan Theophilus, who, like his predecessor, bore the title “Metropolitan of All America & Canada.” Ten bishops were subject to him: Archbishop Tikhon of Western America & Seattle, Archbishop Adam of Philadelphia & the Carpatho-Russians, Archbishop Vitalus of Eastern America & Jersey City, Bishops Arsenius of Detroit & Cleveland, Alexis of Alaska & the Aleutians, Leontius of Chicago & Minneapolis, Ioasaph of Western Canada & Calgary, Hieronymus of Eastern Canada, Benjamin of Pittsburgh & West Virginia and Macarius of Boston. [51] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1936) 7, pp. 104-105. Cf. Part VI. Bishops Theophilus, Tikhon, Adam, Vitalus, Arsenius, Joasaph, and Hieronim were either consecrated bishops before the 1926 schism or were consecrated by the Church Abroad in the interim. Only Bishops Alexis, Leontius, Benjamin, and Macarius received their consecration from the Metropolia.

The reunification of Church unity was celebrated in the ecclesiastical center of both Churches with festive divine services, amidst the participation of numerous hierarchs. In St. Tikhon’s Monastery, Metropolitan Theophilus and Archbishop Vitalis celebrated together with Bishop Adam, Leontius, Benjamin, Hieronymus, and Macarius. A few days later, another service took place in Archishop Vitalus’ Cathedral of the Elevation of the Cross, in New York. [52] Prav. Rus’ (1936) 1, p. 5. The faithful universally welcomed the reunification; many communities joined together in one community because there was no longer any sacramental separation.

The new unity was not of long duration. After the outbreak of the War, there were no more contacts between the Synod and the North American Dioceses. Above all else, ecclesiastical developments in the Soviet Union were judged differently: whereas the Council of Bishops of the Church Abroad condemned the 1943 election of Patriarch Sergius as an uncanonical act, in a decree of November 1943, Metropolitan Theophilus demanded that his communities commemorate the Patriarch, which was tantamount to a recognition of the Moscow Patriarch as head of the Russian Church. [53] Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 53. A total confrontation against the Patriarchal Church and Communism was not possible in practice, because the Soviet Union and the U.S.A. were allies in the war against Hitler. [54] Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 85-103.

Ultimately, this confused stance towards the Moscow Patriarchate destroyed the unity in North America anew. The Church Abroad’s hierarchs Vitalis, Tikhon, Joasaph and Hieronymus, took an uncompromising stand against the Patriarchate; Bishops Macarius and Alexis joined the Patriarchate; Bishops Theophilus, Leontius, Arsenius, and John (Zlobin, consecrated Bishop of Sitka and Alaska, in 1946, after Bishop Alexis joined the Patriarchate) were proponents of autonomy, which would allow them to be subject only to the spiritual and moral oversight of the Moscow Patriarch.

The renewed division of 1946/47 sent the Metropolia into isolation again, which was ended only by the Moscow Patriarch Alexis I’s granting of autocephaly in 1970 because the Orthodox Church in America did not obtain recognition from any national Orthodox Church. [55] Cf. Part V, p. 2. In comparison with the 1926 schism, the position of the Church Abroad in 1947 was much more favorable. It had distinguished bishops and clergy, who had been caring for their communities since the 1920s. The decision of which jurisdiction a community joined lays with the clergy, who chaired the parish council. For the most part, the majority of communities followed their priest; a minority separated itself and joined whomever, in their members’ opinion, was the “canonical” Church leadership. The Church Abroad had the advantage over the Metropolia, in that the newly-arrived émigrés from Europe joined it. Because most of the refugee priests and bishops did the same, the Church Abroad was in the position to send priests to the new communities, whereas the Metropolia had not nearly enough priests even for the old [already established] communities. [56]Seraphim, Church Unity, p. A122 gives a statistical survey of the Orthodox parishes in North America in 1968. At that time the following statistics were given: The Metropolia had over 348 parishes, … Continue reading

At the third diocesan assembly of the Church Abroad, which met in October of 1949, the number of communities was given at 68. Thus, it seems to involve essentially the same communities, which before the reunification had seen the Church Abroad as the true Church for the emigration. Of these 68 communities, 22 were in Eastern America, 10 in Western America and 36 in Canada. These communities had 8 bishops, 3 archimandrites, 6 abbots, 32 archpriests and protopresbyters, and 12 priests and deacons. [57] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1949) 10-12, pp. 54-55. Only two years later, there were already 100 communities. [58] Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 210-212; Prav. Rus’ (1949) 20, pp. 2-11. At the assembly in 1952, Archbishop Vitalus indicated that 2 or 3 communities per month were being founded, since the last session a year previously: a total of 25 communities. [59] Otchet 5-ogo s’ezda, p. 31. At the sixth diocesan assembly, the number of parishes was 110, of these 21 in the U.S.A. and 12 in Canada had been newly founded. Of these 110 parishes, 30 held their own divine services in churches owned by other confessions, and 30 in rented buildings; 43 had their own churches; and 7 parishes had no building in which to serve. Most communities developed a regular parish life: lay brotherhoods and sisterhoods were formed in many communities, which in turn organized Church life; work with the young and the elderly was carried out. Also, many communities set up their own libraries and schools and published parish bulletins. [60] Prav. Rus’ (1953) 9, pp. 7-19.

In 1954, the Church had over 116 communities/parishes and 200 priests, not including readers and missionaries. The largest communities were in New York and Eastern America, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Special attention was paid to the internal mission [among Russians] and also to the mission among the English-speaking non-Orthodox, for which the “American Orthodox Mission” was founded in 1951, under the leadership of Archbishop James (Thomps). [61] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 6; Prav. Rus´ (1954) 10, pp. 4-9; 11: pp. 2-4; Otchet 5-go s’ezda, p. 31. The internal mission’s goal was to strengthen the Faith amongst the Russian flock, especially the youth and the children. In this regard, the importance of church school was proven by the fact that, already in the early 1950s, a tremendous upswing had begun to be evident when everywhere in North America new schools were founded. [62] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. The mission to those outside the Orthodox fold undertaken by Archbishop James, who was retired in 1956, and by many others (notably in the 1970s by the abbots and monks of St. Herman Monastery in Platina and Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Boston) have met with varying degrees of success and have often been hampered by a lack of adequately-trained American clergy and ethnic misunderstandings. Today, Bishop Hilarion is most active in both types of missionary activities.

From 1954, the number of the faithful grew at an essentially slower rate than in the preceding years. From the mid-1950s onwards, Church life began to stabilize. At the same time, regular church building activity developed because the larger and more financially prosperous parishes began to build their own parish churches. Of the 157 parishes existing today in North America, more than 100 were founded after 1947, because many of the older parishes were closed or combined with new parishes (e.g., in New York and other large cities). [63] Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 520-761; 2, pp. 763-803; Otchet eparkhial’noe sobranie. Also, almost all church institutions, such as schools, printing presses, homes for the elderly, libraries, cemeteries and so forth, came into existence after 1947. Of the 12 existing monastic communities in North America, only Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville originated before 1947.

The most important ecclesiastical institutions to come into existence after World War II were the monasteries, which formed the spiritual and ecclesiastical centers of their dioceses, and to which thousands of the faithful yearly go on pilgrimage. [64] Seide, Klöster im Ausland. Moving the Synod to the U.S.A. was of particular importance. In conjunction with this, the New Kursk Root Hermitage, the Synodal building with its Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign, and the Synodal metochion in California were established. The largest new church buildings were the St. Vladimir Church (built to commemorate the 950th anniversary of the Baptism of Russia, in 1938), and the Cathedral of the Joy of All Who Sorrow in San Francisco. Holy Trinity Monastery, in Jordanville, New York, was enlarged and expanded after 1947, due to the influx of monks from Europe and the Far East, by the building of Holy Trinity Seminary and by the installation of a printing press. Holy Trinity Cathedral, with its many gilt cupolas, has become the Church Abroad’s most famous landmark. The vital significance of the monastery for the Church Abroad is documented by the fact that one often falsely hears reference to the “Jordanville Jurisdiction.” [65] Cf. Part IV, Chap. 7.

The schism of 1947 led to the reorganization of the ecclesiastical administration in North America. The pre-1935 administrative membership was resumed: Archbishop Vitalis was appointed head of the dioceses in North America and Canada, and once again bore the title of Archbishop of Eastern America & Jersey City. The Archdiocese of Western America & San Francisco reverted to the rule of Archbishop Tikhon. In addition to this, Detroit & Flint came into existence as its own diocese, and there were two dioceses in Canada: Western Canada & Edmonton under Archbishop Joasaph, and Eastern Canada & Montréal under Archbishop Gregory. The direction of the Jordanville Monastery was transferred to a bishop, Bishop Seraphim of Holy Trinity. Also, a vicariate of Florida was created, subject to the rule of Bishop Nikon.

The most important diocese, with the most parishes, the administrative headquarters of the First Hierarch, and the largest monasteries, is that of Eastern America. Until his repose in 1960, Archbishop Vitalis ruled this diocese. Thereafter, until 1964, Metropolitan Anastasius bore the title “Metropolitan of Eastern America & New York, First Hierarch of the ROCOR.” [66] Prav. Rus’ (1960) 9, p. 12 From 1964 until his repose in 1985, Metropolitan Philaret ruled the diocese. As a rule, two vicar bishops belong to this diocese, who have borne various titles: Bishop Nikon of Florida, Archbishop Andrew of Rockland, Bishop Constantine of Boston, Bishops Laurus, Gregory and Hilarion of Manhattan, and Bishop Daniel of Erie.

The vicariate of Holy Trinity became an independent diocese in 1953 when Archimandrite Abercius was consecrated Bishop of Syracuse &. Holy Trinity. The rule of this diocese belonged from 1953-1976 to Bishop Abercius (from 1967 Archbishop), and from 1976 to Bishop Laurus (from 1981 Archbishop). The vicariate of Florida became the diocese of Washington & Florida in 1967, Archbishop Nikon having assumed the governance thereof.

After his death, no replacement was named, and the parishes were joined to the Diocese of Eastern America. The Diocese of Detroit & Flint was headed by Archbishop Hieronymus from 1946-57. In 1954. A Diocese of Cleveland & Chicago was created, the direction of which Archbishop Gregory assumed. After Bishops Hieronymus and Gregory reposed in 1957, both dioceses were combined and transferred to the rule of Bishop Seraphim, who assumed the title of Bishop of Chicago-Detroit & the Midwest. This diocese consisted of 14 parishes. In 1974 another vicar bishop was appointed for this diocese, Bishop Alypius of Cleveland. Upon Archbishop Seraphim’s death, Bishop Alypius became Bishop of Chicago.

The Diocese of Western America & San Francisco has been in existence since 1930. Archbishop Tikhon ruled this diocese from 1930-63, which at times included Western Canada and Alaska. From 1963-66, Archbishop John (Maximovich) ruled this diocese. In 1966, Metropolitan Philaret took over the administration of the diocese, which, after 1967, was transferred to Archbishop Anthony (Medvedev). From 1951, this diocese had a vicar bishop, Bishop Anthony (Sinkevich) of Los Angeles. This vicariate was changed into an independent diocese in 1962 and included the communities in Texas and Southern California. The title of the ruling hierarch was therefore changed to that of “Los Angeles & Texas.” In 1971, the diocese was renamed of “Los Angeles & Southern California,” and for the Diocese of San Francisco, a vicar bishop was appointed to Seattle. Archimandrite Nectarius (Kontsevich) was consecrated for this position. [67] Tserk. Zhizn´ (1967) 1-12, p. 29; (1972) 1-6, pp. 1-2; Prav. Rus’ (1960) 9, p. 12; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1444-1446. Today, the Seattle Vicariate remains vacant and is administered by Archbishop Anthony of Western America & San Francisco.

It can be assumed that the present administrative structure in North America will also be maintained in the future because reunification with the “Orthodox Church in America” can be all but counted out. The existing dioceses form administrative units of regional communities: Eastern America, the Midwest, Western America, Southern California, and Holy Trinity.

Outside these areas, there are hardly any communities of the Church Abroad. In all of the Midwest, from west of the Mississippi to the California state line, there are only a few communities. The most numerically important communities of the Church Abroad are usually also the sees of dioceses or vicariates, because these communities have larger churches, which are used as cathedrals, though this does not exclude other significant communities and churches in the diocese. Historical reasons also play an important role in the choice of individual episcopal residences.

References

| ↵1 | On the development in North America, cf. Part I, Chap. 4. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 15; Besin, The Orthodox Church in Alaska. |

| ↵3 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 4. |

| ↵4 | Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 17; Ushimaru, Bishop Innocent. |

| ↵5 | Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 17-18; Severnoi Ameriki, p. 3. |

| ↵6 | Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 20-28, 121. |

| ↵7 | Ibid., p. 21. |

| ↵8 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 4. |

| ↵9 | Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 24-25. |

| ↵10 | St. Tikhon’s Monastery is generally accepted as the first Orthodox monastery in North America, although this is not exactly correct because St. Herman had founded a skete called New Valaam in the 1830s on unoccupied Spruce Island, where he reposed in 1837. |

| ↵11 | This refers to the Ukrainian language. |

| ↵12 | The address was delivered in St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York. Today this cathedral belongs to the Moscow Patriarchate after it had been in the hands of the Renovationist “Metropolitan” Kedrovsky. |

| ↵13 | Seraphim, Church Unity. |

| ↵14 | Ibid., pp. 27-28. |

| ↵15 | Bishop Eudocimius did not return to the USA. He joined the Renovationists in 1923. |

| ↵16 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 7. |

| ↵17 | Tserk. Ved. (1922) 4, p. 10. |

| ↵18 | D´Herbigny/Deubner, Evêques russes, p. 93. |

| ↵19 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 383-385. |

| ↵20 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 7. |

| ↵21 | Ibid., p. 384. |

| ↵22 | Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 30. |

| ↵23 | Ibid., p. 31. |

| ↵24 | Bishop Adam was a native Carpatho-Russian, was converted to Orthodoxy by Bishop Gorazd (Pavlik), rector of the small Czech Orthodox Church in Prague, and was ordained by Bishop Stephen. |

| ↵25 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 269-272. |

| ↵26 | Ibid., 5, p. 272. |

| ↵27 | Tserk. Ved. (1926) 17-18, p. 4. |

| ↵28 | Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 9-16; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 385-386; Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 30-31. |

| ↵29 | This alleged decree of Patriarch Tikhon was published in Seraphim’s Church Unity“, p. 126. It was either presented to the Patriarch just for his signature or completely falsified in order to strengthen the position of Metropolitan Kedrovsky against Metropolitan Platon in the ongoing court case over St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York. |

| ↵30 | Cf. Part I, Chap. 4. |

| ↵31 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 28. Cf. on the ecclesiastical schism in North America, the work of Lebedev, Razrukha, which was published in Belgrade in 1929 and comprised the first detailed description of the schism. |

| ↵32 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 6-7. |

| ↵33 | Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 23-26. |

| ↵34 | Ibid., p. 23. |

| ↵35 | Ibid., pp. 36-39; Seraphim, Church Unity, pp. 32-44; Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, pp. 396-398. |

| ↵36 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie 7:390-391. |

| ↵37 | Ibid., pp. 392-396. |

| ↵38 | Tserk. Ved. (1928) 5-6, p. 1. In 1924 the Synod ordered him to return to his diocese of Alaska. When he did not follow this order, he was deposed as Bishop of Alaska. In 1928 he joined Metropolitan Eulogius. |

| ↵39 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, p. 276-278. After the 1926 schism, Metropolitan Platon deposed Bishop Apollinarius as head of the San Francisco Diocese and replaced him with Archimandrite Alexis (Panteleev). (Severnoi Ameriki, p. 29). |

| ↵40 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 5, pp. 278-280. |

| ↵41 | Ibid., pp. 280-282. |

| ↵42 | Vitalis, Motivy moei zhizni. |

| ↵43 | Nikon, Zhizneopisanie, 7, p. 399; Severnoi Ameriki, p. 59. |

| ↵44 | Seide, Klöster im Ausland. |

| ↵45 | Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, p. 520. |

| ↵46 | Cf. Part IV, Chap.7. |

| ↵47 | Cf. the photographs in Russ. Prav. Ts., 1, pp. 521-534. |

| ↵48 | Ibid., 1, pp. 535, 676, 743, 747; 2, pp. 769-770. |

| ↵49 | Severnoi Ameriki, p. 52. |

| ↵50 | Church News (1940) 7, pp. 47-51. |

| ↵51 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1936) 7, pp. 104-105. Cf. Part VI. |

| ↵52 | Prav. Rus’ (1936) 1, p. 5. |

| ↵53 | Seraphim, Church Unity, p. 53. |

| ↵54 | Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 85-103. |

| ↵55 | Cf. Part V, p. 2. |

| ↵56 | Seraphim, Church Unity, p. A122 gives a statistical survey of the Orthodox parishes in North America in 1968. At that time the following statistics were given:

The Metropolia had over 348 parishes, 123 without priests. The Church Abroad had over 109 parishes, 15 without priests. The Patriarchate had over 66 parishes, 20 without priests. Statistics in Eastern Church Review (1968), pp. 70-73 show that: The Metropolia had 411 parishes (174 without priests), 272 priests, and 27 deacons. The Church Abroad had 101 parishes (14 without priests), 120 priests, and 13 deacons. The Patriarchate had 77 parishes (39 without priests), 55 priests, and 13 deacons. |

| ↵57 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1949) 10-12, pp. 54-55. |

| ↵58 | Severnoi Ameriki, pp. 210-212; Prav. Rus’ (1949) 20, pp. 2-11. |

| ↵59 | Otchet 5-ogo s’ezda, p. 31. |

| ↵60 | Prav. Rus’ (1953) 9, pp. 7-19. |

| ↵61 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 6; Prav. Rus´ (1954) 10, pp. 4-9; 11: pp. 2-4; Otchet 5-go s’ezda, p. 31. |

| ↵62 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 5. |

| ↵63 | Russ. Prav. Ts. 1, pp. 520-761; 2, pp. 763-803; Otchet eparkhial’noe sobranie. |

| ↵64 | Seide, Klöster im Ausland. |

| ↵65 | Cf. Part IV, Chap. 7. |

| ↵66 | Prav. Rus’ (1960) 9, p. 12 |

| ↵67 | Tserk. Zhizn´ (1967) 1-12, p. 29; (1972) 1-6, pp. 1-2; Prav. Rus’ (1960) 9, p. 12; Russ. Prav. Ts. 2, pp. 1444-1446. |