In the course of the last seven months, the field of Russian history in the modern period suffered irreplaceable losses. On December 27, 2018 Dmitry Anashkin died in Moscow; followed by Vladimir Rusak on April 20, 2019 in Baranovichi, Belarus and Aleksandr Gavrlin on June 20 in Riga.

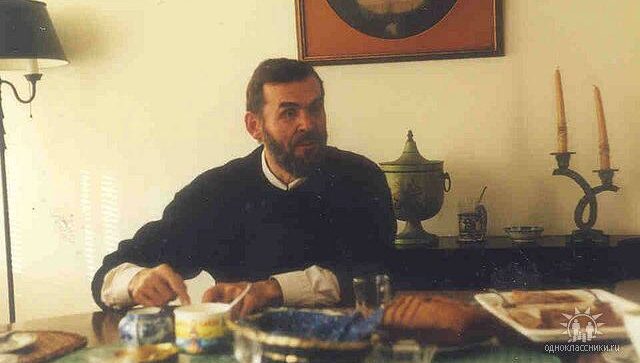

Vladimir Stepanovich Stepanov was born in 1949 into a churchgoing family in Belarus. In the 1970s and 1980s, he worked as a member of the editorial staff of the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. In the mid-1970s, having already been ordained deacon, he began to work on a book on the persecutions of the Church from 1917 onwards, gathering material from open sources such as periodical publications from the revolutionary and Soviet eras. Father Vladimir’s work Svidetel’stvo obvineniia (Witness for the Prosecution), which he published under the pseudonym Rusak, was distributed in typescript samizdat and subsequently sent off to the West for publication.

On one Sunday in Lent in 1983, at the akathistos service to Christ’s Passions (Passia) in the Our Lady of Kazan Cathedral in Vitebsk, Protodeacon Vladimir Stepanov gave a sermon on the Russian New Martyrs, as a result of which he was stripped of his registration papers by the commissioner of the Council for Religious Affairs and sent to serve temporarily in Zhirovichy Monastery. In 1986, Fr. Vladimir was arrested and sentenced to twelve years in prison. After his release, he resettled in the USA in 1989.

In 1988, I brought the three volumes of Witness for the Prosecution, which had only just been printed in Jordanville, back with me to Russia from my first triз to the Russian diaspora in America. The book raised many questions about the relationship between Church and State in the Soviet era.

I first met Vladimir Stepanovich in 1990, when I was granted a student visa to come to Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville. The incoming class at Jordanville that year numbered 21, and the majority of these students were from the Soviet Union. One could not say that we were met with hostility in Jordanville, but there was also no feeling that the “Church Abroad” party considered us to be their own. Vladimir Stepanovich would interview the incoming students in order to find out how serious they were in coming here. I recall that in my own personal history, a red pencil mark was made next to my mention of having been in the Komsomol.

Vladimir Stepanovich subsequently taught the history of the Russian Church to our class for two years. At that time, he was beginning to study the history of the Church, as he did in the USSR, only this time about that of the Church Abroad. He sent a memorandum to the Synod of ROCOR Bishops in 1993 encouraging them to join forces with the Russian Orthodox Church in working toward a spiritual revival. After he finished teaching in 1995, Vladimir Stepanovich moved to Washington, where he worked as a watchman at the cathedral of St. John the Baptist. Our paths diverged entirely and only crossed again on one further occasion, on June 22, 2015. Vladimir Stepanovich was looking for a place to spend the night, and I invited him to our house, where, incidentally, the Rusak family had previously lived. This was how this interview came into being. While speaking with him, I asked him what kind of student he remembered me as being. “You and Tsurikov were good students!”, he said. He said that the reasons for the distance that I had always felt between myself and him had to do with my Hebrew background. We parted ways pleasantly and peacefully. On April 20, Lazarus Saturday, Vladimir Stepanovich departed this life in his native town of Baranovichi, two months short of his seventieth birthday. This translation has been made possible by a grant from the American Russian Aid Association – Otrada, Inc.

Deacon Andrei Psarev,

July 1, 2019, London

In the Russian Church Abroad in the 1980s, people knew the names of prisoners of conscience, of confessors of the faith. And, of course, Deacon Vladimir Rusak was among those whom Regan demanded be released. And so, in 1988, you were released and received an invitation to come to Jordanville and teach there…

No, that is not how I was invited. I came with my wife just before Easter, and we met with Vladyka Laurus then.

That was in 1989?

1989, yes. We spoke with him, but no invitation was made. It was the current Vladyka Peter who suggested I come to fill in for him and teach a subject instead of him, for example, Russian Church History. “The recent period, after the Revolution – yes, please, I will be very happy to teach it, I know it well.” “But the whole history of the Church? You’ll have to teach it all.” Thus, I had to catch up quickly on the things that I had forgotten.

What was your first impression of Jordanville like?

I remember my first impression very well. The Church we had come to was of our own kind, everything was in Church Slavonic, and yet the parishioners were young: women in hats. This was something out of the ordinary for somebody from the Soviet Union. I was struck by the fact that such a place even existed here on Earth. I have since seen a lot of churches, in the States and elsewhere, but this first impression has stuck with me. We were given a place to stay by the Klars – they simply handed over the keys. We met them at Easter. Lidia Mihailovna Klar (the wife of Seminary Dean Evgenii Osipovich) told us, “I left the key in the flower bed, in a little box by the front door. You can let yourselves in when you get here.” We got there and the key was in fact there. And so, we spent a year living opposite the Klars.

And so, you started teaching in August 1989?

Yes. We came to the States in April. I had taken a large bag with me, but it was half empty: the only things in it were my papers. My wife, Galina also had a small bag. Even though the Lutherans had purchased tickets for us and paid for extra baggage, we didn’t have enough things to fill even one bag. I didn’t have a typewriter, or anything at all, really. I called my friend, Iurii Nikolaevich Lednev [who recently passed away], and asked him, “Iura, do you know where I can buy a typewriter?” “What do you need a typewriter for? We are living in the computer age. Buy yourself a computer!” We happened to have some money on us for the start, quite a lot by our standards. Fr. Georgii Skrinnikov also helped us. He just gave us some money, and I bought a computer. Fokin also helped me to set it up, to take the first steps. Even before the start of the academic year, Evgenii Osipovich Klar explained that we had to prepare academic programs in all disciplines for the [New York State] Education Department, which I succeeded in doing. Then I started teaching. Then, two years later, Vladyka Laurus suggested that I could teach canon law, as well. He was either exhausted or else affected by his illness. I worked in this capacity for seven years.

The seminary here is small, but you had experience studying at the Moscow Theological Academy, which is an enormous educational institution.

Of course, one cannot compare them.

Whereas everything here is small, low-key.

All the subjects required to train priests are taught here. So low-key though it may be, everything one needs can be had here.

It is almost as if you have lived two or three different lives in your time. These were completely different phases: your work for the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate, your book Witness for the Prosecution, your arrest, imprisonment, your life abroad, coming into contact with the reality of life here. Let’s talk about opposition to the Moscow Patriarchate. What stance did you take regarding the matter of the Church Abroad establishing parishes within the territory of the Moscow Patriarchate?

Remember the report to Vladyka Laurus that you mentioned?

Yes.

It wasn’t a mere report, but rather a hundred plus pages of continuous text [For the link see the Russian original]

Perhaps there was an abbreviated version of it around?

There may well have been, but, unfortunately, I have lost it. The matter of these parishes was discussed in it. The year was 1993, and everybody here was excited at this idea. As for myself, though, I could see that this undertaking was unlawful and felt a very painful response to it. I was, after all, a teacher of canon law and was tasked with making sense of such things. In my report, I didn’t mince my words. I said what I thought and dubbed these parishes “illegitimate children of the Church Abroad”.

Initially, I wrote a short letter to Metropolitan Vitaly, and then to the Synod. I could see and sense that this [the establishment of these parishes] was not doing anywhere good. Of course, I couldn’t have expected that this letter would be read at the Synod and had no hope that they would be so naïve as to listen to me. Vladyka Laurus read it out, but made only one remark: “You referred to Vladyka Antony Medvedev by the name Sinkevich”. So I mixed up his surname. That’s all he said to me.

I have nothing bad to say about Vladyka Valentin Rusantsov. He is a practical man and, as far as I can tell, very devout. He is being accused of collaboration with the KGB. Naturally, it is the [Moscow] Patriarchate that is accusing him: so much is clear. I have met him on multiple occasions. All those who are not in agreement with the general line being pursued by the Patriarchate have been silenced. Their resistance exudes something of a sectarian spirit – at least for me – but their faith and traditions are the same as ours, no questions asked. Moreover, the fact that they are persecuted is attractive and commands respect. Yes, in fact, one ardent apologist for the establishment of parishes was Bishop Gregory Grabbe. He wrote a huge number of reports about these parishes to the council, that is, the Synod of Bishops. He even accused the leadership of the Church Abroad of adopting an incorrect stance with respect to these parishes.

Yes, it is true, he did adopt such a position.

Vladyka Gregory is another interesting figure in the Church Abroad.

Now there is something of a tendency to demonize him, to portray him as the culpable for all its problems. I think that is unfair.

I think it is fair. He played a very difficult role in the history of the Church Abroad and there is no way of escaping this fact. I have read his works very attentively. It so happens that I have also found a huge number of inaccuracies and, to put it mildly, strained interpretations in the works of many émigré historians. They can be found in the works of Professor Andreev, Father Mikhail Polskii, and Bishop Gregory Grabbe. If one were to gather them all together, they would make up a whole volume.

Such research has been conducted on the publications of Fr. Georges Florovsky. Thomson checked his footnotes and sources, and found many faults in them.

References are one thing. It is possible to reference something incorrectly, especially when one has a lot of references. But one finds a huge number of false statements concerning documents that one can in theory find.

Incorrect quotations?

And statements. These authors make independent statements, they do not only cite others. This includes Vladyka Greogry and Fr. Mikhail Polskii. There are a lot of inaccuracies.

Including in the “Canonical Basis”?

Yes, of course. I will cite a number of examples from memory. Fr. Mikhail writes: “N. came out of exile, met with Metropolitan Peter, and he said…” Which “N.”? This “N.” is long since dead and buried. Why not refer to him by name? Or “Bishop A. K.” Here we have a historian operating in terms of letters rather than living people. Or: “Right before the war, when Patriarch Tikhon was in hospital, one nurse recalled that Vladyka Petr came racing out…” Whom is this aimed at? For the diaspora, however, this is the norm.

Perhaps it is due to a lack of precise information?

If the information isn’t there, it is better to leave such things out. Historians are not meant to make such errors.

But these are not pieces of serious academic research.

I have encountered such errors in research, and even in serious research. Such as when Fr. Victor Potapov received orders from the Synod to attend to “Russian affairs.” Just think about this statement from the point of view of the language he is using. But if, after all, we are talking about the Russian Church, then shouldn’t there at least be normal Russian in use? So, it happened that Vladyka Laurus simply left my report, which I had compiled based on various materials and on analysis of various known and unknown sources, without any consequences at all.

As one might have expected.

On the other hand, it is good that there wasn’t any scandal. I think that this was thanks to none other than Vladyka Laurus.

Yes, that is in keeping with his style, his personality. But at the same time, you refused to reconsider your position, and what came out of it? A confrontation.

I have always had, and continue to have to this day, a great respect for Vladyka Laurus. In fact, I wrote an article to mark the anniversary of his death. It was published in a journal in Moscow. Here, though, did anyone write anything in Pravoslavnaya Rus’ to mark the anniversary?

I am afraid not.

I am also afraid that no one did. I wrote a large full-format article [the link is in Russian original] for a major newspaper, not just some tabloid. I wanted to send it here, but I think there must have been something wrong with my computer. As a matter of fact, the 25th anniversary of Vladyka Laurus’ episcopal consecration also passed unnoticed. The current Vladyka Peter was telling me, “Volodya, do something. It’s bad.” I wrote an article – I have kept a photocopy of it. You see, Vladyka Laurus did a lot for the Church Abroad.

Yes.

That is, if one considers the reunification of the churches to be a great accomplishment. I was pro-reunification from the very beginning. At one point, [Rasophore Monk] Boris asked me: “What are you in the Church Abroad for?” I replied, “I am in the Church Abroad by accident.” Well, accidentally or not accidentally, that’s how it happened. Is it an Orthodox Church? It is Orthodox. Am I Russian? I’m Russian. There’s no difference between them for me. I was never a politician; for me, there was always just one Church.

I had known about the Church Abroad before, too, since the time when I worked as an editor. When I travelled overseas for the first time, to Denmark, we went to a church in Copenhagen. We were there together with the rector of the church and Vladyka Pitirim. The rector didn’t know how to behave with a bishop from the [Moscow] Patriarchate. I became interested and started chatting with the rector, Fr. Alexander. That was my first encounter with the Church Abroad, albeit not a very close one. When I got to see everything with my own eyes, I realized that the scale was different, including in the seminary. But the people! I was in awe when I first saw how calm, quiet, reverent everything was. In the Soviet Union, one could go into a Church and even during the Eucharistic Canon, people would be walking around. Here, however, whichever Church I visited, the services were conducted in an orderly and reverent fashion. Of course, this is very attractive and comforting. Yet if the Church Abroad had not rejoined the Russian Orthodox Church, in the decades to come it would have met a quiet end. I am almost certain of this.

Even though émigrés from Russia are filling the churches?

They do not solve the overall problem.

That is to say that they do not supply leaders for the ROCOR?

Of course, they do supply them. This is a profound and beneficial function of theirs. Though I do think that the leadership of the Church Abroad could exert a more active influence on the situation inside Russia.

Of course. In my opinion, this relates first and foremost to Neo-Stalinism, which is gaining momentum in Russia. The Church Abroad could express its concern about this fact.

Of course. And that’s not all. There is a huge number of points of attack for the Church Abroad.

But here there is a question of propriety. Once I was speaking to Archbishop Mark of Berlin, and he was saying that Russia has its own peculiarities, as do we.

An excess of modesty is not a virtue here. The ROCOR is a part of the Russian Orthodox Church, as is written in its statues. It therefore has not only the right, but also the obligation to exert an influence on the situation within Russia.

There was an attempt to do so by opening parishes there.

An attempt, yes.

But now, after reunification, it turns out that it is not so easy to single out specific problems.

Yes, especially if one considers that that particular attempt basically failed.

As a result, a gulf emerges, with us tending to our own affairs, whereas the church within Russia has its own bishops and it is not considered proper for us to give them advice. Although with regard to Stalinism, such thoughts have come to mind.

Yes, it is a serious matter. I think one ought at least to speak out about it. I am not saying that the influence of the Church Abroad has the potential to turn the situation around, but I feel a need to speak out about the problems that exist there.

For example, by saying that our bishops are concerned by…

Saying that is like telling anekdoty in the kitchen under the Soviet regime.

Well, no – minutes of meetings are one thing, but if the Synod were to make an official statement, that would be something else.

There doesn’t even need to be an official statement by the Synod. Bishops already represent the principle of authority in the Church. Each bishop has the right and the obligation to voice his thoughts on any pressing issues. I do not mean on technology or outer space, but rather on everyday questions. Such is his obligation. No one in the Church Abroad is doing this. While people, mankind as a whole may have a future, it seems, at least to me, that the Church Abroad does not.

Do you mean that everything will sooner or later become part of one single Moscow Patriarchate?

Yes. Let them learn Russian, and let the Russians learn Chinese.

Of course, we cannot say how the situation will develop, but it seems to me that if relations between Russia and the West deteriorate, the Church Abroad will find its niche. People will keep coming to replenish the ROCOR, since it is an émigré church. But if the barrier continues to disappear, the difference between the Patriarchate and the Church Abroad will come to be insignificant.

Yes, time will tell.

Interviewer: Deacon Andrei Psarev