The Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in China used to send priests to distant areas of China in order to conduct Lenten and Festal services for communities of Russian émigrés that did not have permanent churches. Bishop Victor (Svyatin) of Peking, the Director of the Peking Mission, thus sent Priest Dimitry Uspensky, a clergyman of the Diocese of Peking of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, to Hong Kong. A small community of Orthodox émigrés had already formed in Hong Kong, and they had sent a request to Peking to resolve the question of their pastoral care.

After arriving in Hong Kong, Father Dimitry came to an agreement with the rector of the Anglican Church of St. Andrew to hold services in that church initially. During his first visit to southern China, Fr. Dimitry Uspensky also visited Xiamen (Amoy), Guangzhou (Canton), Macao, and Manila. Upon returning to Peking, Fr. Dimitry raised the matter of the necessity of constructing house chapels in southern China with the head of the Mission. A colony of Russian émigrés living in Hong Kong also approached Bishop Victor in Peking with a request to send Father Dimitry Uspensky to serve full-time in Hong Kong.

By force of Decree No. 37, issued on July 10, 1934 by Bishop Victor of Peking, house chapels were founded in Guangzhou (dedicated to the “Unexpected Joy” Icon of the Mother of God), Macao (to the Trinity), and Manila (to the Iveron Icon of the Mother of God). Fr. Dimitry Uspensky, who was made head of the Hong Kong Deanery and Rector of Saints Peter and Paul Church in Hong Kong (Diocese of Peking), was entrusted with the pastoral care of these churches. A church in Xiamen was also incorporated into the Deanery from April 1937; it was dedicated to Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker. In Hong Kong itself, up until a permanent church was opened at 8 Middle Road, services were held in the Anglican Church of St. Andrew in Kowloon.

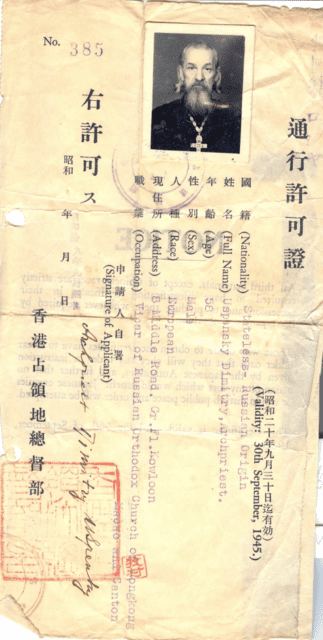

Apart from the church itself, the Orthodox community in Hong Kong included a Ladies’ Group devoted to the upkeep of the church and educational activities, a Charitable Fund, a Church Building Fund, and an amateur choir. In the early 1940s, the community in Hong Kong proposed constructing a new, permanent church. Architectural plans were even prepared for it. The Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, however, prevented it from being built. Not only English subjects, but also Russians, were made prisoners in Japanese camps during the war. Fr, Dimitry was able to keep the parish together in this difficult time for the community. Fr. Dimitry, as a disciple of the Peking Mission and an Orientalist, longed to carry out missionary work among the Chinese, but a lack of means and the overall atmosphere prevalent in the Russian community at the time, forced him to devote most of his pastoral efforts to serving the Russian émigré community.

The end of the Second World War and the liberation of northern China from its Japanese occupiers came to be defining factors in the shift in relations between the Orthodox Church in China and the Moscow Patriarchate. In July 1945, an Episcopal Assembly took place in Harbin, which was then occupied by Soviet forces, and passed a resolution in favor of reunification with the Moscow Patriarchate.

The Diocese of Peking had to resolve the question of its jurisdictional status independently. Saint John of Shanghai, Vicar Bishop of the Diocese of Peking, and a lawyer by training and expert in canon law, convinced Archbishop Victor, his ruling bishop, to adopt the new jurisdiction. On July 31, 1945, he wrote to him:

“[…] Following the decision of the Diocese of Harbin, and in view of the absence, for a number of years, of information about the Synod of the Church Abroad, any other solution would make our diocese entirely independent and autocephalous. There is no canonical foundation for this type of independence since there are no doubts as to the canonicity of the newly recognized Patriarch. Relations with the [Moscow –tr.] church hierarchy are also possible, with the result that the Decree of November 7, 1920 is not applicable. At present, there are no grounds for us to remain a self-governing diocese, and we ought to follow the same course as the Diocese of Harbin. The name of the Chair of the Synod of the Church Abroad ought still to be commemorated at services, since, according to the 14th Canon of the First-Second Local Council, one may not arbitrarily cease commemorating the name of his Metropolitan Bishop. The commemoration of the name of the Patriarch, however, […] must be immediately introduced throughout the whole diocese by a Decree of yours.”

Archbishop Victor agreed with Saint John’s proposal and, in August 1945, he sent a request by telegram to Patriarch Alexis of Moscow asking to receive him and Bishop John into his jurisdiction. The Hong Kong Deanery followed its ruling bishop in adopting the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate.

On December 27, 1945, the Synod issued Decree No. 39 concerning the reunification of the dioceses of the Far East with the Moscow Patriarchate.

Regular communications by post and telegraph within China were delayed owing to military operations, with the result that the Patriarchal telegram of January 11, 1946, notifying the Diocese of Peking that it was to be received under the omophorion of the Moscow Patriarchate, did not reach Peking; accordingly, news of this decision did not reach Shanghai. The question of church affiliation in Shanghai as well as in Peking was left open, though Bishop John began commemorating the name of the Patriarch at services even before he had received the news from Moscow. Victor Bishop in Peking pursued the same course of action. At that time, on September 28, 1945, His Eminence Bishop John of Shanghai received a telegram from Geneva sent by Metropolitan Anastasy, the Primate of the Russian Church Abroad, notifying him that the Synod of the Church Abroad was still functioning (the telegram could not be sent to Bishop Victor in Peking from Geneva, so it was addressed to his vicar in Shanghai). On September 29, 1945, Bishop John transmitted the telegraphic message with Metropolitan Anastasy’s request to Peking. Recognizing the need to remain subject to a superior ecclesiastical authority, Bishop John restored his former relations with the Synod of the Church Abroad, receiving and carrying out separate instructions from it.

In an open letter to his flock, Bishop John wrote:

ROCOR priest Antony Serafimovich serves a panikhida over Russian graves in the cemetery in Hong Kong

“The governing authorities of the Church Abroad have seen fit that the Church should continue to take responsibility for our pastoral care, and has notified us of this fact as well as informing His Eminence the Head of the Mission of it. Consequently, we do not consider it possible to take any decisions in relation to this question without the instruction and approval of the authorities of the Russian Church Abroad. As late as the Council of 1938, in which we took part, it was decreed that when the time will come for us to return to our native land, the hierarchs of the Church Abroad should not act separately, but rather the entire Church Abroad should present an account to an All-Russian Council of the acts it has performed while living in forced separation. Communications concerning the restoration of full canonical communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, received by Archbishop Victor on Great Saturday in response to his request to His Holiness Patriarch Alexis last August (1945), were a cause of sincere joy for us, since they allowed us a glimpse of the beginnings of mutual understanding between two parts of the Russian Church divided by a border, and of the possibility of mutual support of two centers that gather the Russian people together as one, inside and outside our Fatherland. If they can strive together towards a single common goal and act separately according to the conditions in which each finds itself, the Church inside Russia and the Church abroad will be better able to achieve both their common aims and the particular ones that each has, up to the point when a complete reunion will be made possible. At present, the Church inside Russia has to heal the wounds that militant atheism has inflicted upon it and free itself from the bonds that are impeding the fullness of its internal and external functioning. The goal of the Church Abroad is to prevent the children of the Russian Orthodox Church from becoming dispersed, and to preserve the spiritual values that they have brought with them from their homeland, as well as to spread Orthodoxy in the countries where they are living. This was indeed the purpose of the acts of the Synod of Hierarchs of the Church Abroad that took place in the city Munich, under Allied occupation, on the anniversary of the defeat of Germany.”

In early 1946, an obvious difference of opinion began to emerge between Archbishop Victor and Bishop John concerning the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Peking. On June 15, Bishop Victor signed a decree relieving Bishop John from the administration of his vicariate and appointing Bishop Juvenaly (Kilin) as vicar. As early as June 2, he had sent a brief to this effect to the Patriarch in Moscow. After his sermon of June 16, Bishop John announced to those present at the liturgy that he had received orders relieving him of his duties as Vicar of the Diocese of Shanghai, but that he did not intend to submit to this decree:

“I will submit to this decree only if it can be demonstrated to me, by way of Sacred Scripture and the law of any one country, that oath-breaking is a virtue and keeping one’s oath is a grave sin.”

On June 20, 1946, Bishop John issued a decree making known the resolution of the Synod of Bishops of the Church Abroad, which gathered in Munich on May 20, 1946, to form a diocese of Shanghai of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, headed by Bishop John, and to “relieve Archbishop Victor of the administration of the Diocese of Shanghai”. The Synod of the Church Abroad, without the consent and knowledge of the ruling bishop, established an independent Diocese of Shanghai within the precincts of the Diocese of Peking. From this moment on, it was no longer possible for Archbishop Victor and Bishop John to concelebrate. The message from Munich that declared the Vicariate of Shanghai to be an independent diocese was a surprise for Bishop John; however, he viewed his appointment to this see as an ecclesiastical obedience and accepted it.

The clergy in Bishop John’s diocese consisted of twelve priests and three archdeacons. When the new diocese was declared to be established, the Orthodox populace of Shanghai split across the two jurisdictions: that of the Patriarchate (up to 10,000 people) and that of Bishop John (up to 5,000 people).

The Chinese Civil War, the defeat of the Kuomintang and their allies, and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China led to the mass flight of foreigners from China. Many émigrés regarded Hong Kong as an intermediate point on their voyages to places of permanent residence (Australia, South America, the United States). Thousands of émigrés settled down in Hong Kong, where they were provided with shelter, sometimes for a comparatively long period of time. For the majority of Russian émigrés who came to Hong Kong with the wave of refugees from Shanghai and North Korea, Church life under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate was unacceptable for political reasons. For some time, they were allowed by Fr. Dimitry Uspensky to pray in the garage of the Saints Peter and Paul Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. Nevertheless, they never joined Fr. Dimitry’s community.

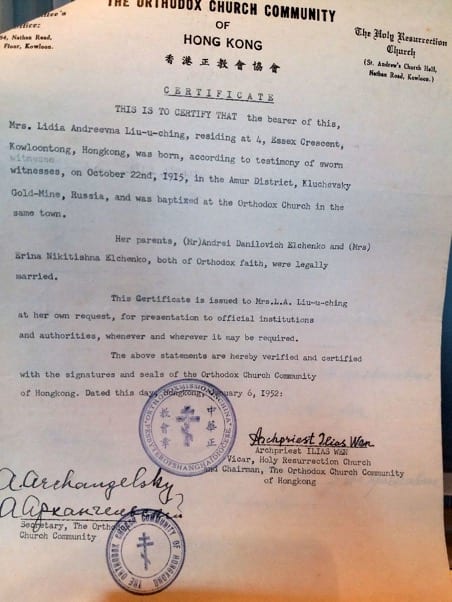

In February 1949, Archbishop John of Shanghai issued a decree establishing the Holy Resurrection parish in Hong Kong under the jurisdiction of the Shanghai Diocese of the ROCOR. The Chinese clergyman Archpriest Ilias Wen was appointed rector of the parish, and he arrived in Hong Kong from Shanghai on March 1, 1949. The parish reached an agreement with the Anglican church of St. Andrew to rent from the latter semi-subterranean premises for the purposes of holding services. The Holy Resurrection parish received continual support from Bishop John, who visited Hong Kong twice between 1949 and 1951. The guests of the parish regularly included clergymen who stayed in Hong Kong en route from China to other countries. One of the 1956 issues of Pravoslavnaia Rus‘ mentioned that Priest John Volkov, who was traveling to Brazil; Hieromonk Dimitry (Obukhov), whose onward journey was to take him to Brisbane; and Deacon George Pisarevsky, had all stayed in Hong Kong. The Holy Resurrection ROCOR parish did not have a formal legal status in Hong Kong, and was thus unable to issue official marriage licenses. The burial of parish members in the Colonial Cemetery of Hong Kong also took place with the permission of Fr. Dimitry Uspensky, with notes to this effect being made in the register of the Saints Peter and Paul parish. Nevertheless, the Holy Resurrection parish did issue identity papers on demand, such as were required in order to obtain further documents necessary for emigration to the New World, as well as baptismal and marriage certificates.

Archpriest Ilias Wen led the ROCOR Holy Resurrection parish in Hong Kong up until his departure to the United States of America in September 1957. The parish afterward remained without pastoral care for almost a year, and only barely coped with the maintenance costs of the church. Many parishioners of the Holy Resurrection community went over to Fr. Dimitry Uspensky at the Saints Peters and Paul church. In September 1958, Archpriest Theophan Raphailovich arrived from Manchuria; he served the Holy Resurrection community until March 1959. He was the last priest of that parish. The archives of the Western European diocese of the ROCOR preserve documents connected with the life of this community. Among them, a testimony to the care of Bishop John (Maximovich), is an Easter greeting from 1960, which he sent from Brussels to the parishioners of the Holy Resurrection community. In the absence of a priest and with services no longer being performed, the life of the Holy Resurrection community of the ROCOR in Hong Kong ceased in 1960. Those Orthodox Christians who remained in Hong Kong continued to attend services at the Saints Peter and Paul church under Archpriest Dimitry Uspensky.

Article based on materials from the archive of the Saints Peter and Paul Church in Hong Kong, the archive of the West American Diocese of ROCOR, and ‘Pravoslavnaia Rus’’.