The following article was commissioned by the Moscow-based Nezavisimaia Gazeta but not published.

On my way from Sheremetyevo Airport, I was gazing on the snow-bound Moscow after staying away for 3 years and reflecting on this world I have found myself in once again – a world that operates entirely according its own laws. All that came before this – New York and the West in general – was beyond the ocean, left far away; now it was just you and Russia, one on one.

However, my encounter with the ecclesial Russia didn’t bring up the sharp ‘East-West’ contrast that I had noted on my arrival to Moscow. Only yesterday, I was teaching at the Holy Trinity Theological Seminary in northern New York and today I am sitting in the Synodal library based at the former St Andrew’s Almshouse on Moscow’s Sparrow Hills. There was no contrast whatsoever between the two; the atmosphere of Russian Church was exactly the same as the experience of being among the parishioners of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR). There was one marked difference, however, which was immediately apparent and that was the might of the Russian Church structure. Knowing this, it was all the more surprising that the Moscow conference had been organised on ROCOR’s initiative, a Church whose flagship monastery, the Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Jordanville is nowhere as populous as the Moscow Sretensky Monastery where the delegates were housed. This juxtaposition of power on the one hand and modest circumstances on the one was evident even during the conference. The very fact of the ROCOR clergy participating in the conference at all was perhaps even more significant than the papers they had prepared and delivered. It gave a glimpse of the cross section of the world of ROCOR, the views, problems and specific reaction of its clergy and laity brought up abroad. Had the unification of the ROC MP and ROCOR which G.A. Rahr discusses in his interview entitled ‘The Karlovac Church Has No Future’ (NG-Religions 4th December 2002) already taken place, there would hardly have been any need for these clergymen to leave their populous parishes and travel to a conference all the way in Moscow. In this way, even the absence of eucharistic communion between the hierarchy of the two parts of the Russian Church might prove cathartic in the end.

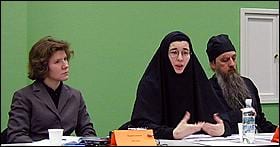

The ROCOR clergy delegates at the conference included some of its more venerable representatives while among the new generation of church workers one would want to single out in particular nun Vassa (Larina) from Munich. She delivered a paper on the question of salvation in different circumstances (oikonomia) as understood by Metropolitan Anastasy (✝1965), the First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad and his other contemporary ROCOR bishops.

Among the papers presented by the Russian historians, I was particularly struck by the one delivered by S. G. Petrov (Novosibirsk) entitled ‘Communities of the “True Orthodox Church” in Connection with the Police Investigation of the Usurpers’ Case (1930-1950)’ Based on the records of the Soviet law-enforcement agencies of the time, it is clear that Seraphim Pozdeev, the founder of the so-called Catacomb ‘Gennadian’ hierarchy was himself an ‘usurper’.

Altogether there were 25 papers presented in the course of the 3 day-conference, all dealing with the events in the history of the Russian Church in Russia and abroad from 1930 to 1948. Such an intensive pace of work left little time for discussion but a lively debate followed the presentation of the summing-up document. Fr Nikolai Artemoff, the secretary of ROCOR’s German diocese and the originator of these conferences on modern Church history, found himself mercilessly ‘squeezed’ by the document’s correct but completely implacable definitions as set out by the conference’s co-presidents, Fr Boris Danilenko (the director of the Synodal Library) and Fr Nikolai Balashov (the External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate).

The contentious nature of the issues facing the conference was reflected in the acknowledgement in the summing up document of the existence of pre-conceived stereotypes in the mindset of both parts of the Russian Church arising from their different life experience. It was obvious that it was a matter of church politics as much as academics. The statement acknowledging ‘the role of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in preserving the traditions of the Russian Church piety and safeguarding her sacred shrines’ could be said to be the summing-up document’s main achievement.

In general, the conference can be credited with a genuine desire to explore the reality of historical developments in the Church of the 20th century and the moral implications arising therefrom. I think any conference on the modern history of the Russian Church should be willing to analyse those facts that are at variance with the accepted historical stereotypes advanced as the one or the other ‘party line’. No that I advocate indifference. To my mind, a part of the mission of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad is to present opportunities for frank discussion to the whole of the Russian Church, for example of the position of those hierarchs who regarded the course taken by Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky ✝1943) as an usurpation of the episcopate’s right to govern the Church collegially. Within Russia, this position was mostly strongly represented by the hieromartyr Metropolitan Cyril of Kazan (✝1937). Despite living in an atheistic state, he managed to present a worthy opposition to Sergius’s ‘wisdom’ when he found himself unable to reconcile his conscience with the diktats issued to the Bishops’ Council of the Russian Church. The subsequent censure unleashed by Metropolitan Sergius on his opponents – Metropolitans Cyril, Joseph, Anthony and others, both at home and abroad – using all the ‘canonical dialectics’ at his disposal was, in my opinion, a most controversial aspect of Metropolitan Sergius’ conduct at the time. This conduct needs a canonical assessment by the fullness of the Russian Church in the light of both the decisions of the All-Russian Church Council of 1917-1918 and the position of Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow (✝1925) and Hieromartyr Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsk (✝1937). The Council should also evaluate the course of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad according to the same canonical criteria. However, the very idea of convening a church council that could be called the rightful successor of the Local Council of 1917-18 is currently no more than a fantasy.

Conferences on the subject of the history of the Russian Church in the 20th century seem to be a necessary preparatory stage for such a council. And yet, there are still no takers among the Russian church publishers to make the proceedings of the first such conference in Hungary available! How then can the Russian Church become aware of the deliberations at these conferences? It would appear that the forces within the ROC-MP who desire further dialogue with ROCOR are less influential than those who adopt a policy of waiting vis-a-vis ‘the Karlovac Church with no future’

A single conference can examine a historical period of no longer than 30 years. It thus follows that more time is needed to evaluate the whole of the period from 1917 to the end of the 20th century. What further events might take place during that time? Because ot the unpredictable nature of many factors, it is impossible to predict the the trajectory of the historical development with any certainty.

The first conference took place in November 2001 in Hungary, on neutral territory within the jurisdiction of the Serbian Orthodox Church. At that conference, all of the delegates in holy orders were the ROCOR clerics; the Russian side was represented only by professional academic historians. There were altogether 11 papers presented. The Moscow seminar organised by the MP DECR in May 2002 could be regarded as a response to the Hungarian conference. The summing-up document, approved by the Holy Synod of the MP stated that the participants concluded that ‘within the sphere of establishing relations with ROCOR, there was no constructive alternatives to engaging in a dialogue’. I interpret this statement as an acknowledgement that a mere monologue exhorting all to return to the fold of the Mother Church has only led to a dead end. On the other side, ‘The Reply of the Council of Bishops to the Brotherly Epistle of the Bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate’ conceded that ‘without a doubt, even we have sometimes made mistakes and that there may be sins within our church life. We will be grateful if you will frankly point these shortcomings out to us for correction’. These conferences organised by ROCOR are a proof of its openness to continuing the dialogue with the Russian Church.

The question remains however whether this process will indeed succeed in reconstructing the complete picture of the historical events of the Russian Church in the 20th century in all its contradictory fullness and subjecting it to a proper Orthodox analysis.