It takes five hours, the same as from New York to Jordanville, but the difference is that one travels here from Moscow on a minibus, and the village is on the banks of the Mologa River. Mologa! Is there any name more Russian? Mologa is the name of the city that was submerged underwater in Soviet times. It is in the Tver region, and I came here to meet Sergei Alekseevich Guerbilsky.

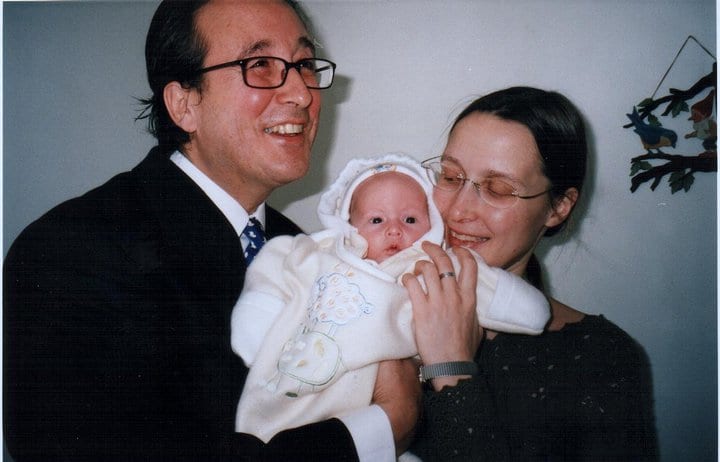

Sergei (Sergio) was born into a family of Russian anti-communists, “Whites”, they were called, and after the Second World War they moved from France to Brazil. Then they emigrated to Montreal, and came to study in Jordanville, work in art, translation, and the restaurant business.

His meeting with the Russian ballerina Olga Pavlovna Lavrovskaia changed everything: Sergio returned to the land of his ancestors, to find peace on the banks of Mologa, participate in the restoration of the church building, and in the parish life of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God in Borisovskoe.

The Russian immigration, the Russian Church Abroad, was very focussed on Russia, but did they put their money where their mouth was? How many Israelites did come back after the [70 years in captivity in Babylon? The same question might be applicable here. You are here; it is kind of very natural that you came to the land of your forefathers.

Yes, back to your roots, and you are quite happy with this, but can you talk about the influence of the Russian Church Abroad after the collapse of the Soviet Union?

That is quite difficult. Obviously, I am descended from the first emigration (1920). By 1990, after 70 years, people were quite established in the west. The Russians in France became rather French. The Russians in America became rather American. They had their ways. They had settled. Obviously, in the 1990’s thinking of immigrating [to Russia] not everyone could even think of that because it is very difficult. In the following ten years, things became easier. Very few people are immigrating [to Russia]. Of the many young people that come here, looking for their roots, and some find it, others don’t: some figure that they do not belong here; maybe they do not belong; maybe they miss the comfort, the well-organised society, culture, music – I don’t know, but it is extremely difficult. To me it was easy. To me the transition was totally natural. Maybe it was because I had been in many [different] cultures and many situations in my life. I was somewhat romantic and idealistic and to me it was natural to confront the problems that surface over here with regard to immigration, with regard to arrogance, and with regard to incredible bureaucracy. The upside to me is very real, especially the Church, the martyrs, the monasteries, the individuals, the people – to me, there is a richness there that is very real, and which I don’t find in the West.

You cannot expect from people who, like you, were brought up in the diaspora (they were not born in Russia) to move to what for them would be a new country.

To another culture, even. My brother has become totally Canadian.

Did he ever visit you [in Russia]?

He never visited and he’s not interested and that’s another story. He would feel totally like a stranger, totally estranged.

What is your opinion regarding the positive contribution of the Russian Church Abroad towards Russia?

Not much! Before the [Berlin] Wall came down, it did a lot.

Staying informed, perhaps?

Staying informed; safeguarding the Tradition; safeguarding church life and, purely psychologically, [being] a church that was independent, real, and rather holy, especially throughout the first three first hierarchs. Then, as Russia started reviving, the Russian Church Abroad started losing somewhat of it spirituality, in a way. I remember Father Alexander Lebedeff saying we ‘over-eat’; the Russian Church Abroad has become fat, while Russia started doing the opposite. Exactly the opposite was happening here. But now it came a very long way but some people [here] are saying that in the old days, previously it was considered that the major passion, (искушение) the temptation of the monk was adultery: it was always considered the hardest passion to fight. Now they are saying that a new trend, if I can use the word for a new passion, is a love for money. Somebody was saying that even in Mount Athos now ‘money money, money’ – everything is money! Is this what is happening in the Russian Church [in Russia]? Partially, but to what extent, I really don’t know, because I am not that close to everything that is happening.

Staying informed; safeguarding the Tradition; safeguarding church life and, purely psychologically, [being] a church that was independent, real, and rather holy, especially throughout the first three first hierarchs. Then, as Russia started reviving, the Russian Church Abroad started losing somewhat of it spirituality, in a way. I remember Father Alexander Lebedeff saying we ‘over-eat’; the Russian Church Abroad has become fat, while Russia started doing the opposite. Exactly the opposite was happening here. But now it came a very long way but some people [here] are saying that in the old days, previously it was considered that the major passion, (искушение) the temptation of the monk was adultery: it was always considered the hardest passion to fight. Now they are saying that a new trend, if I can use the word for a new passion, is a love for money. Somebody was saying that even in Mount Athos now ‘money money, money’ – everything is money! Is this what is happening in the Russian Church [in Russia]? Partially, but to what extent, I really don’t know, because I am not that close to everything that is happening.

You are also witnessing to the events connected with our reconciliation. Why did some people reject reconciliation? Why did it happen that some people found it impossible to accept the Moscow Patriarchate?

It’s a frame of mind and misinformation, and a certain heritage from Soviet days, obviously, where bishops and clergy were partially KGB. There was a lot of that, either by choice or not.

Of course, it was closely associated with the system.

Everything was closely associated with the system because the system had penetrated all social and cultural levels of life in the Soviet Union.

I do not have much information about it but my feeling was that…

…fright: they were afraid.

That’s exactly it, because people who were brought up in the Soviet Union – they are a different type of people. They speak the same language (although even some people would argue that it is not the same language because they don’t really speak the sort of language…)

…Homo sovieticus.

Right. So, therefore, psychologically, [those who rejected reconciliation have a] fear of people of a different mind-set [and are] just willing to wall-off from them.

Yes. And also, the Russian Church Abroad being very fragile, in a way, because it was spread throughout the world, it wasn’t rooted through centuries in one specific place with a specific culture, etc., and had to survive in a strange land, it was a very closed society which, in a way, could start stagnating somewhat. When the prospect of opening up towards new frames of minds, new cultures, new ways of looking at things (not canonically or dogmatically but just different people), people were afraid of losing that which throughout decades they were safeguarding, which was the so-called purity of the Church.

Yes. And also, the Russian Church Abroad being very fragile, in a way, because it was spread throughout the world, it wasn’t rooted through centuries in one specific place with a specific culture, etc., and had to survive in a strange land, it was a very closed society which, in a way, could start stagnating somewhat. When the prospect of opening up towards new frames of minds, new cultures, new ways of looking at things (not canonically or dogmatically but just different people), people were afraid of losing that which throughout decades they were safeguarding, which was the so-called purity of the Church.

Also, their identity was very…

…identity and purity of the Church, yes.

And also, why do you think so many from your generation from the Church Abroad stopped attending church services?

That’s a difficult question.

There are probably several layers, right?

There are many reasons probably, whether cultural or spiritual…

But do you think language plays any role in the case of, for example, your brother perhaps, if he would have access to services in French – would it be helpful?

No, I don’t think so.

So the whole ethos of the Church became redundant for him: it doesn’t really relate to the modern mind-set?

Mind-set or metaphysical aspirations – where everything is at hand. ….[Гром не грянет мужик не перекрестится]. You only turn to God when you have problems. Lack of problems – in the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s?

Not really. Everybody has his share of hardships, right?

Obviously, but it’s relative. I can’t answer that. It’s partially cultural, partially spiritual. How do you deal with living in a society with a different set of morals?

Let’s rephrase it. What should the Church do in order to help them to remain in the Church? Is there anything the Church can do better in order to keep those people?

I can’t answer that because the Church should not change. People should change.

That’s fair enough.

And I find that, actually, parishes of the Church Abroad have a much stronger social life as compared to Russian. Here you go into a church and leave and you get to know a few people, but that’s it. You don’t go and have a cup of tea and пирожки afterward. You don’t have parties like the Russians abroad do for Christmas and Easter.

What about Annual Parish Meetings here?

Is there such a thing? (Laughs) I don’t know. I don’t see them.

What about the Parish Council?

No. I think there is an ustav, whereby the priest is very much the sole leader within the Church. They do have Councils and so on but the word from the nastoyatel (rector of the parish), from the head priest is law.

Right. It seems there is no strong tradition: apparently, people don’t know what to do with those organs.

Neither is there that tradition outside of the Church with regard to Councils, etc. In the States pretty much everybody is familiar with a “Board of Directors”, “management teams”, and so on. There is a whole business aspect of society, of organizing society [which is] so much more developed. I remember [Boris] Jordan [American businessman of Russian origin] – the one from New York: he was head of NTV and he created Renaissance Capital. There was an interview with him and they asked him “What could make Russia more efficient?” He said “A little more Anglo-Saxon blood.”

Interesting. Thank you, Serge, thank you very much. That was a lot of food for my thought.

Interesting!

Hello Sergei,

During the quaranteen many of us have taken to reminiscing, which I just did by reading your interview. It is fascinating that you immigrated from Brazil to Canada to Jordanvile. I have down the reverse, from Canada to Jordanville to Brazil, where I have been living for the last 6 years.

If you can, drop me a line,

Mark Midensky

fabaomarcao@hotmail.com

You can find me here: https://www.facebook.com/sergio.guerbilsky

Cheers!