It is an open secret that generally the Russian Church Abroad cannot pay its clergy sufficient salaries. Seminarians spend strategically important years getting a decent theological education from Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville, but then they are on their own and have to put in even more efforts to get a “real” degree that would allow them to provide for their families. (This situation undermines the high dignity of priests’ office and a change is overdue.) In the meantime, Reader Ivan Jigalin tells about the consistent strengths of Jordanville monastery and seminary. Ivan was born in Australia in a Russian family, emigrated from Chinese Inner Mongolia in the early 1960s.

First of all, it is really great to reconnect after all these years.

Yes, it is.

And I definitely have very fond memories about our time in Jordanville. What do you do now?

Fr. Gabriel Makarov, Rdr Ivan Jigalin, Metrop. Vitaly, Rdr Pavel Iwaszevicz, Arcb. Pavel, an unidentified kid. Appr. 1986

I work as a correctional officer, a prison guard. The official name is correctional officer. This is at a maximum-security prison here in Victoria.

Right, for how long have you been working in this position?

It has been now over thirteen years. When I finished seminary in 2001 I went to Russia with a couple of alumni — Kostya Glazkov and Igor Dubrov — and I went there for about a month or a month and a half. I came back to Australia and within about three months I got a job for prison guard.

Right. Has your seminary education played any roles as far as you can see in the part that they selected you for this job or do you just don’t know this?

I’m not fully aware if it was or not. I know that one of the recruiters said there was a question mark for them as to why someone would apply in a prison after going through all the training of seminary for a priest. They asked me directly why I applied for the prison; and that was well. When I finished up seminary, my past experience, work that I had done was in computing, computer programming and also in the building trade and I wasn’t very interested in either of those fields. So I was looking for a different direction. I was still uncertain. I know a lot of people finish seminary and they straight away say that “I want to be priest” or “I am already a priest” and go down that line straight away, but I didn’t have that within me, and so I looked to see what I wanted to do. So, I applied for a lot of jobs, a hundred jobs, just by newspapers. On the computer I just had a pro forma which I changed according to the ads that I was answering, I would change my resume slightly to answer the criteria and so on, and for the prison guard — to be honest, I didn’t even realize I applied for the prison, only when I received a reply from them.

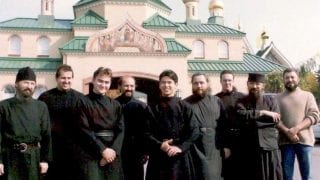

Rdr Ivan, second from the left, with students and brotherhood of Holy Trinity Monastery and Seminary from Australian and NZ diocese of ROCOR

Within a prison there are various areas you can work in, and depending on what area, duties slightly change. But the most common duty is looking after the welfare of the prisoners. And that is performing day to day basic tasks which includes accounting, making sure the security, that they are all still there, organizing their meals, their work schedules and any other legal needs, social needs and so on for the prisoners. So basically as a prison guard you stand, we don’t stand around so much as you see in movies and so on, like standing there like someone holding a baton, we don’t have any batons or anything in the prison. We are just among the prisoners, and all we have as far as our tools are our communication skills and we have a radio, and so therefore we interact with the prisoners throughout the day for basic needs.

Yes, but I assumed that the people were there for a long time because it is maximum security. So therefore you kind of have special relations because you are kind of, I don’t want to say family, but maybe I should say family. I don’t know if it is the proper word. You are a person on whom they depend on very much. I think, because you are there every day and so you are their first port of reference if they need anything and so on, so it kind of is like a special relation as far as I can think …

Yes, that is correct. You do develop relationships with the prisoners within the scope of the prison. So generally you keep any personal information from them. That is more of a security issue. But they do get to know you and when you are spending twelve hours a day among these prisoners, obviously they get to know certain things about you: your mannerism, the way you conduct yourself, the way they conduct themselves and so on. So you do get to know each other. Conversations are more about general things, general topics, so of course in Australia, people are very much into sports, so conversations always come up about sports and the local football teams, cricket. Here in Australia cricket is big and just general politics, occasionally it would come into it. Religion doesn’t come into it so often, but most find out very quickly that I’m a person of the faith just by the conduct. They straightaway see just by the way I’m conducting myself and so on, because you can interact in different ways, but people see through all the faсades and so on and so then, you know, people are people and if you are with them twelve hours per day, of course they are going to see through any faсade you have on so they are very quick to pick up on that and they may ask certain questions.

Right. And the Lord said “I was in prison and you visited, I was hungry and you fed me.” So I think this sort of dimension is lacking in our Christian life. I don’t really know people who do go to prison, or do other social work. That’s why I was very interested in carrying this conversation, because I thought, okay, I think you do the best you can to be a Christian within the guidelines of your job. I just want to know, what do you like about your job, basically?

Well, I do get a lot of satisfaction for going through a day without incident. That is a big thing. You go for a day, and it is a quiet day, nothing happens, so a boring day is a great day.

Wow!

Rdr John (on the right) In the day of graduation from Holy Trinity Seminary, 2001, with his brother, now, Hierodeacon Panteleimon

Okay, that is for starters, on the one level. I know when I started, and I was thinking more about getting into the job. Of course prayer is a big part. And so before I started every day, I thought what was an appropriate prayer. And so I made up my own. I couldn’t find anything, really, in any literature. But the closest thing was, say, people going into war. And so then I looked for even troparia for saints and the closest one I found was for the Holy and Great Martyr Saint George. I don’t even know the translation in English “as the deliver of captives.” So I prayed to Saint George every day, every day, and I feel that is very appropriate going into it. And then, we talk about the theory that you learn, you read a book, that is all theory. And we talk about love and, for most of us, we experience that among those who are closest to us and our friends. And when they say you have got to love your enemies and that in every person you can see Christ, that gets harder when you are in a situation where you are dealing with rapists, murderers and the so called low-life. How do you put that together with what you read and have learned? That in this person there is Christ, a created image and likeness of God? And that is every person, so that you start looking at things deeper, and a deeper meaning is associated with a personal experience. From a personal experience, you are looking at it. And a lot of that, you very much see in your everyday dealing with people, people who disagree with you, people who argue with you, people whom I have had to restrain and continuously remember that they have created in an image of God. It is fascinating when you stop to think about it, but a lot of times when these things are happening during a course of a day, I don’t really have time to stop and think about it. I have to do my duties and occasionally while in duties, prayer will come forward. But a lot of times it is very difficult, putting the two together.

I know it would be difficult for me to overcome natural fear. I remember when we talked last time in Jordanville, you said that when you come into a room, you would always see that your back would be covered. You want to see the door, kind of naturally. So, the nature of the job and what comes is fear. That would be an issue for me, you know, how do you deal with this, basically with fear? And you said you really don’t have any weapons. You said you rely on your conversational skills which is great, but at the same time can they take you as a hostage? I mean, you are among people who basically have nothing to lose.

Yes, there is always that possibility and you can become compulsive. A lot of times during the day, you start lowering your guard a bit and you constantly have to remind yourself that you are in a prison, you are in this environment, and there are people here, who as you say, got nothing to lose. Three things I find comfort in, which help get through that. Well one is definitely prayer and another the notion that the God is protecting me, and I am there for a reason; and the other one is the rapport. I suppose that they all are interconnected. The rapport that you have with the prisoners. So if you go out of your way like you see in movies to make life difficult to other people, if you treat them like animals, they will react like animals. If you treat them like a person, they will react like a person. That is what I’ve found. For the most part, that’s in life, that is anywhere, in a prison, in your everyday life dealing with people, it is the same thing. You treat them like a dog, they will react like a dog. If you treat them like a person, they will react like a person, and that is what I have found, even in this environment. At the same time, I’ve got to be aware about what is around me. A lot of the time, things come naturally. Now saying things come naturally, I’m already thinking about exit routes, I’m thinking about how many people will be there, how many people will stop my way out, all that. Well that comes naturally now to me, you know, it is like breathing or doing a natural thing. Already straightaway, I walk into the room, I’m already looking that there is a door, that way or this way, there are people over there, that’s going on over there and even when I’m discussing things with people, I’m half aware, I’m aware of what is happening around me. Where is that person going? What’s happening there? I am aware of that without being consciously aware about it.

I understand. How did the seminary help you? That is the first question. The second question is how did the seminary not prepare you? Let’s start from the first one. How did, your education in Jordanville help you on a daily basis in what you do?

Well, it is interesting, probably one of the best things that prepared me for what the prison would be like was the daily routine. Because the daily routine is very similar to the monastery daily routine, you get the gist of it. So in the morning you have someone coming around with a little bell, ringing it to wake every one up…

At what time?

Well in seminary was about 5 o’ clock or 5:30, but in a prison, it is a quarter to 8 in the morning, so 7:45 in the morning, we don’t ring a bell, we get a speaker and we announce that it would be time for hands on track muster. So that is when we are going to count them, they have to come up into the little hole in the doorway, we open it up then they put their hand there. We make sure that they are there, that they are alive, they made it through the night and so on. So in a similar way, someone is going past through the seminary hall waking everyone up. We go past to make sure that they are awake. After that we, normally, have in seminary, we have morning prayers or you go to church or waking up and doing a little routine among each other and so on. And they will go off to work as you did in the monastery. You go then to church and then off to work. So you have that routine up until lunchtime and then lunchtime and they have the same routine. 12 o’clock is lunch and so we count them again, lunch is served. In monastery we come there and a little word would be said and at the same time a little word would be said here, if any announcements need to be made and the same thing then after lunch. In the seminary, after our studies, after lunch we have our obedience work. So here they go off to their work. Then in the evening, same thing, dinner, but they’ll eat at 5 o’clock typically, and they’ll have their dinner. While in the monastery they would have it a bit later at 7 o’clock. So the routine structure is interesting because I just compared it and it is similar to a monastery. In a monastery, people have their own cells and in a prison they have their own cells and they have their own items in there. Even those items, how important they become to individuals. It is the same thing in the monastery, people have their little things in their individual rooms, their cells, and the prisoners also have their own little things. Some are hoarders, some like keeping their things neat. It is so similar on a practical level in a lot of ways, so that is one thing that has definitely helped me, I understood the routine. I suppose anyone who has been in the army role understands a similar routine. But then apart from that definitely living in a community, close quarters among people. You do understand that you have got to make allowances for being in that close proximity of other people and so you have to give a little extra space to people. You know, people get frustrated and so on, and a prisoner is more so. So from the seminary, to forgive and quickly move along and not hold grudge — you definitely have to use that in a prison. You can’t hold a grudge, you can’t hold a grudge against anyone regardless if they had done something to you, whatever. Move along. That has happened, move along; move along to the next thing. And then of course there is also all the other subjects that you go through, all the theology and so on. It is definitely about trying to better yourself and through your actions, your own actions, rather than getting other people to get better. That is a big thing. There is no point of me standing up in the middle, among the prisoners and trying to quote them scripture and trying to tell them how they are supposed to live their lives and all these things, you know. People will laugh at you. They will laugh at you right out, but just by them observing you and your actions and the way you interact, the way you speak, don’t swear, you listen to what people are saying and so on. That is definitely a big part and people see that. I like to think that just by my example, that’s doing something, that prisoners think about what they do and so on: on those lines rather than on any specific sort of educational, higher up words or anything like that.

Well in seminary was about 5 o’ clock or 5:30, but in a prison, it is a quarter to 8 in the morning, so 7:45 in the morning, we don’t ring a bell, we get a speaker and we announce that it would be time for hands on track muster. So that is when we are going to count them, they have to come up into the little hole in the doorway, we open it up then they put their hand there. We make sure that they are there, that they are alive, they made it through the night and so on. So in a similar way, someone is going past through the seminary hall waking everyone up. We go past to make sure that they are awake. After that we, normally, have in seminary, we have morning prayers or you go to church or waking up and doing a little routine among each other and so on. And they will go off to work as you did in the monastery. You go then to church and then off to work. So you have that routine up until lunchtime and then lunchtime and they have the same routine. 12 o’clock is lunch and so we count them again, lunch is served. In monastery we come there and a little word would be said and at the same time a little word would be said here, if any announcements need to be made and the same thing then after lunch. In the seminary, after our studies, after lunch we have our obedience work. So here they go off to their work. Then in the evening, same thing, dinner, but they’ll eat at 5 o’clock typically, and they’ll have their dinner. While in the monastery they would have it a bit later at 7 o’clock. So the routine structure is interesting because I just compared it and it is similar to a monastery. In a monastery, people have their own cells and in a prison they have their own cells and they have their own items in there. Even those items, how important they become to individuals. It is the same thing in the monastery, people have their little things in their individual rooms, their cells, and the prisoners also have their own little things. Some are hoarders, some like keeping their things neat. It is so similar on a practical level in a lot of ways, so that is one thing that has definitely helped me, I understood the routine. I suppose anyone who has been in the army role understands a similar routine. But then apart from that definitely living in a community, close quarters among people. You do understand that you have got to make allowances for being in that close proximity of other people and so you have to give a little extra space to people. You know, people get frustrated and so on, and a prisoner is more so. So from the seminary, to forgive and quickly move along and not hold grudge — you definitely have to use that in a prison. You can’t hold a grudge, you can’t hold a grudge against anyone regardless if they had done something to you, whatever. Move along. That has happened, move along; move along to the next thing. And then of course there is also all the other subjects that you go through, all the theology and so on. It is definitely about trying to better yourself and through your actions, your own actions, rather than getting other people to get better. That is a big thing. There is no point of me standing up in the middle, among the prisoners and trying to quote them scripture and trying to tell them how they are supposed to live their lives and all these things, you know. People will laugh at you. They will laugh at you right out, but just by them observing you and your actions and the way you interact, the way you speak, don’t swear, you listen to what people are saying and so on. That is definitely a big part and people see that. I like to think that just by my example, that’s doing something, that prisoners think about what they do and so on: on those lines rather than on any specific sort of educational, higher up words or anything like that.

Right. So therefore it is difficult to expect, I mean about again, what you wish the seminary would supply you with, what kind of subjects you wish were taught at the seminary, which might have helped you in your ministry and what you do right now.

That’s a hard one. Definitely a very hard one, but then again all the basics, all the basics that the seminary tell you, all the basics of Christianity; the commandments, the New Testament, lives of saints. All those basics, you draw upon those for example, all the time. I know among the American evangelists, it is a catchphrase, ‘What would Jesus do?’ Alright I don’t think so much in those, but what examples can I draw from so what examples immediately the people I have interacted with in the seminary, the saints that we read about. And then of course the prime example is our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. So that is the prime example, of course obviously. But you have all these different areas to draw upon rather than any specific subject. You mention a subject, I would probably say self-defense would be a good one.

That’s a hard one. Definitely a very hard one, but then again all the basics, all the basics that the seminary tell you, all the basics of Christianity; the commandments, the New Testament, lives of saints. All those basics, you draw upon those for example, all the time. I know among the American evangelists, it is a catchphrase, ‘What would Jesus do?’ Alright I don’t think so much in those, but what examples can I draw from so what examples immediately the people I have interacted with in the seminary, the saints that we read about. And then of course the prime example is our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. So that is the prime example, of course obviously. But you have all these different areas to draw upon rather than any specific subject. You mention a subject, I would probably say self-defense would be a good one.

Can you tell me about someone whose life changed and you were very happy. Can you give me some examples of like people’s sort of transformation if possible or something like that; when you saw it you were very relieved with it, you felt very happy about what you do because you saw how you were able to help somebody and so on. Were there any cases that you may mention like that?

That is a difficult one because unfortunately the people you deal with will say one thing and can be going in one direction. But their actions show that down the track either that they would relapse or that wasn’t the case. That they were just putting on an act and the only ones I can judge by are the ones that don’t return back to prison. Among the prison population, we are told, at the time during my training, we were told something like 70% will return to prison after their release. That is quite a high number to come back in. And so much percentage who would die out of prison, and there is a small percentage who would just disappear and be never heard from. And then it was something like 10% who would go and live a supposedly normal life and so those ones are the success, the ones who don’t come back into prison and go live a normal life. They are the ones you don’t have anything more to do with. So from one point as a correctional officer you don’t see any success in your job, really, because the real success are the ones you do not see again and that little 10%, I would like to think that they are the success and be happy for them. I know of a few who have now, ten years on, who haven’t come back in. They are people whom I have personally dealt with in the system. So for success stories that is all I can tell you. I don’t know of any personal situations, I can sort of just generalize on that.

Well, there have been things that have made me think throughout the tragedies that go on there. I worked for a while where we processed visas coming in and out of the prison. And so of course there are the families. For the most part it is the wives and the children. And the children are the very hard ones because I saw them coming in as newborns and then growing up and becoming toddlers and starting to talk and so on and it is sad because they come through and they knew the whole procedure, so they come through and they are already showing their insides of their pockets, they are lifting up their feet. They know the whole procedure, so it becomes almost normal. Prisons to them become normal and so talk about breaking the cycle; unfortunately, a lot of the prisoners have uncles, cousins and so on. The whole family is into the whole criminal element and they are born, you see them come in. Unfortunately, you look at them and it does break your heart that these kids haven’t got much of a chance. For the most part, you get hardened up working there. But there was a situation where a mother and a daughter were visiting constantly and they were very polite. I never had a problem with them. I knew them quite well. They would visit three times a week. The daughter was about sixteen years old, the mother in the mid-thirties. We got news one day that they had both overdosed on drugs. Both of them, both died on the same night. They weren’t together, they were in a separate environment, but they both died the same night, the mother and the daughter. I knew these people coming in and out and I had to come down with one of the supervisors and go to the prisoner himself to inform him that both of them had passed away. That is one of the really hard things that I have had to do on the job. That was something I never got used to and hope I will never get used to: seeing little kids and seeing their family members and seeing that happening. you realize then that you can do everything physically and put all the support and so on; but ultimately everything is in God’s hands. And so the biggest thing we can do is the same with anything and with any job. And I know moreso in a prison that it is prayer. The biggest thing is prayer and everyday to pray for all the workers, all the visitors and all the people in the prison. I know in the general presence for all the people in the prison, and seeing all these things that happen, you understand why that’s there. You know, that this is the church, the church has drawn on their own experiences and knows about this and included it in the prayer rule. And that is very interesting for me.

Yes, so you think seminarians might learn a lot from just going. We are now thinking of setting up a master program, Master of Divinity, which would require our seminarians or people who enroll straight into this program, graduate students, to spend time in hospitals and prisons. And so this would probably be very useful, a very useful part of their formation so…

Definitely, definitely going into these different environments definitely helps so much. Like I said, it forces you to really look at things deeper and outside your normal, comfortable environment on the couch, watching TV. We are used to that. That is a comfortable situation and so is everything that happens around us, even the most serious situations apart from possibly some health problems within the family, but most things are fairly comfortable. Where as when you go into environments like as you say, hospitals, or prisons and so on, that is going out of their comfort zone and really would open eyes of a lot of people and start thinking of things in a broader way. I would include the third world countries and people who have seen that and visited are the same sort of thing. It would help in a big way. You talked about not many, there is not much ministry in Australia. We do have a couple of priests. There is one in particular, an Aboriginal priest who has visited and is part of a role as an Aboriginal elder, but is a priest as well. He visits them in the prisons and he sees it as a big part of his ministry.

Definitely, definitely going into these different environments definitely helps so much. Like I said, it forces you to really look at things deeper and outside your normal, comfortable environment on the couch, watching TV. We are used to that. That is a comfortable situation and so is everything that happens around us, even the most serious situations apart from possibly some health problems within the family, but most things are fairly comfortable. Where as when you go into environments like as you say, hospitals, or prisons and so on, that is going out of their comfort zone and really would open eyes of a lot of people and start thinking of things in a broader way. I would include the third world countries and people who have seen that and visited are the same sort of thing. It would help in a big way. You talked about not many, there is not much ministry in Australia. We do have a couple of priests. There is one in particular, an Aboriginal priest who has visited and is part of a role as an Aboriginal elder, but is a priest as well. He visits them in the prisons and he sees it as a big part of his ministry.

Right, right, right. What about us the Orthodox, are there any priests whom you see, who come regularly to your correctional facility?

There is one Greek priest who comes and he is there regularly and he visits a few of the prisons around the area so that is virtually his full time job from, he is part of the Greek diocese, I have spoken to him. There is not a huge, and he is mainly a minister among the Greek Orthodox in prison; it isn’t a huge number. I have seen a few Russian Orthodox come through, but the numbers are very small and that situation where they have been in prison, the priest would come for specifically one person, not for any group or so on. So he would come and visit a person one on one.

All right, I understand, but, basically, relations between prisoners of what I understand in America are quite brutal and violent. Is it the same relationship between the people in the ward, is it also violent or is it more less they kind of behave and they don’t turn to violence and brutality among themselves?

So for the most part the prisoners are profiled when they come through and so going on past history, what type of crime. They would be allocated to certain parts or certain prisons for starters and then certain parts of the prison. So whether it is mainstream or segregated, and also the type of crime. The type of crime will also keep them away, especially any crimes to do with children or sexual nature. They’re segregated from the mainstream because even among prisoners, they detest that type of crime. And so the mainstream prisoners, they wouldn’t last among the rest of them. For the most part, they are reasonably civilized. There is their own little hierarchy that goes on. They have their own little groups and, if there are conflicts, that is when sometimes trouble does arise. From what I have observed, it is nowhere near as badly as what you see on TV or what you see in American prisons. I have watched some of the shows like the harshest prisons and so on. It is definitely not at that level here in Australia. There might be one or two individuals who have to be dealt with in that manner. But for the most part it doesn’t seem to be on that scale.

And the last question I would like to ask you, what would you wish the current seminarians in Jordanville, where we are going through all sorts of transformations now; all the instructions are now in English here and we have young kids who come fresh from school or from home-school. There is a generational and cultural gap, so anyway Jordanville is to large extent is the same as it was when you came here, where you would see a lot of things which are dear and familiar to you, but at the same time you see that nothing stays put. What would you say to people who are now seminarians in Jordanville? What would be your wishes and suggestions, can you share with us?

Okay, I know this may sound funny coming from me, but I still think obedience (послушание), in the sense of the “must” of obedience is a big part of it. You don’t realize that so much until you leave the monastic setting and, although you think you may know everything, you may know how to do things better, maybe there is someone else to do this. Maybe at the time you may question all these things; but there is a reason why that is happening. And so obedience is such as big part which will then help you, I think, so much in your endeavors after seminary, whether you go on to become a priest or you don’t go and you’re still part of the parish life. But to understand that and to understand, you have to live it. You have to live a life to understand what it means obedience, again, in a monastic setting. If you go for it in your seminary and you finish understanding what that means, I think that is a big part.

I’ll explain why that is important to people and particularly people who aren’t in the church at all or don’t have a good understanding of what it means obedience in particular, monastic obedience. Obviously, it is not, when you say the word ”obedience” it’s like someone thinks, a parent tells a child to go do this and the child has to obey and do whatever’s told. Obedience, whereas monastic obedience is something on a greater spiritual level and that is giving up your own will and in doing so, you are relieving yourself from pride. Because everything you do is not your will, your life doesn’t become me, me, me, I, I, I. It is over to someone else and ultimately over to God so whatever you are doing and you can apply that everywhere. So then it doesn’t become even on a church level with doing this project because ”I said so.” We are doing this project because it is good for the community, it is good for God’s temple, it is good for God’s will. So everything then becomes not an ego, not an ego move. It then becomes a spiritual move because you have taken yourself out of it. That is why I find the obedience part is just so important. When people become clergy, even though they are in charge of their parish and they head it, there is always a danger of falling into pride that it is me, me, me. ”I said, so you do,” then becomes obedience. [Instead of to say] ”I’m here filling the bishop’s will. ” So then your obedience; so then therefore everything isn’t about you. It is about the church and fulfilling the wish of the church and that is why again. Alright, okay, I hope all that helps.

I’ll explain why that is important to people and particularly people who aren’t in the church at all or don’t have a good understanding of what it means obedience in particular, monastic obedience. Obviously, it is not, when you say the word ”obedience” it’s like someone thinks, a parent tells a child to go do this and the child has to obey and do whatever’s told. Obedience, whereas monastic obedience is something on a greater spiritual level and that is giving up your own will and in doing so, you are relieving yourself from pride. Because everything you do is not your will, your life doesn’t become me, me, me, I, I, I. It is over to someone else and ultimately over to God so whatever you are doing and you can apply that everywhere. So then it doesn’t become even on a church level with doing this project because ”I said so.” We are doing this project because it is good for the community, it is good for God’s temple, it is good for God’s will. So everything then becomes not an ego, not an ego move. It then becomes a spiritual move because you have taken yourself out of it. That is why I find the obedience part is just so important. When people become clergy, even though they are in charge of their parish and they head it, there is always a danger of falling into pride that it is me, me, me. ”I said, so you do,” then becomes obedience. [Instead of to say] ”I’m here filling the bishop’s will. ” So then your obedience; so then therefore everything isn’t about you. It is about the church and fulfilling the wish of the church and that is why again. Alright, okay, I hope all that helps.

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev

- G4S Australia and New Zealand. http://www.au.g4s.com/

Very interesting interview!

This work can help to get a good answer on The Great Judgment.

As in my previues comment I would like to repeat that this work can help to get a good answer on the Great Judgment. It is very important to provide Orthodox Christian books to people, mission conversations, Katathism, Orthodox Christian prayers room, Chapels, Churches inside of the prisons.

The prisoners can help to make icons, candles and other things for Holy Liturgy.

Regarding the question about Orthodox clergy that visit prisons in Australia, it appears the interviewer did not realise that the Aboriginal elder reader Ivan spoke of was in fact Father Seraphim Slade, a priest of the ROCOR diocese of Sydney, Australia and New Zealand. Father Seraphim’s mission based in Gunning, New South Wales, is dedicated to St John of Shanghai and San Francisco. He is a broadcaster, and a very well known figure in indigenous Australia and has also worked in the NSW correctional system for many years. I think that is something worth noting.

The ROCOR Rev.Father Seraphim (Slade) is a descendant of the Aboriginal tribes from south-eastern Australia, he is the first Canonically Ordained Priest of Aboriginal descent in Australia.

An Aborigine, he began his missionary work among the natives of Australia as facilitator in March 2008 (ordained into the priesthood by Met.Hilarion the First Hierarch) with Saint John’s Mission in Gunning which is the first specific Canonical Orthodox Mission to the Aboriginal people of Australia and the Torres Strait Islands.

He has worked in Prison Ministry since 2004, in the state No:1 Maximum Security Centre at Goulburn NSW.

Fr Seraphim has worked in varying rolls within Corrective Service NSW and was appointed by the Minister of Justice as a Statewide Aboriginal Official Visitor in 2015, lately concentrating on correctional facilities of southern area of N.S.W. per September 2017.

He seems to be recovering well from prostate cancer, gaining back his strength, having also taken herbal medications. Слава Богу!