I first learned of Father Herman in Moscow in the year 1989 or 1990. I was friends with Roman Vershilo, now the editor of the web portal antimodernism.ru, and at his place I first saw the first issue of Russkii Palomnik [Russian Pilgrim], with an icon of Sts. Sergius and Herman on the cover, which was decorated with the colors of the Russian three color flag. This was the first issue of the journal after Fr. Herman’s revival of this well-known per-revolutionary periodical. At the time Roman, together with Stefan Iakovlevich Krasovitskii, was inspired by the establishment of a Moscow affiliate of the Valaam Society of America. Later at the home of Zoya Aleksandrovna Krakhmalnikova I saw some sort of pamphlet from the monastery in Platina. There on the cover was an artistic photograph of the new (post-fire) Platina church in snow, set before a bright blue sky.

Having become a “conscientious” [сознательный] member of the Russian Church Abroad, I judged Fr. Herman for the turmoil he caused, as a result of which he was defrocked by ROCOR in 1986. I recall that when he would visit the monastic cemetery in Jordanville in the 90’s, the thought would not even enter my mind to show him any kind of friendliness. I recall some American monks, all but schema-monks, standing next to the cathedral in San Francisco during the glorification of St. John in 1994; although, they looked more like hippies than traditional Orthodox monks. Clearly, these were Fr. Herman’s recently converted former adherents of the Holy Order of MANS.

When I arrived at Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville, I came across an issue of Orthodox Word in which news was given of some mysterious catacomb bishop from Russia, carrying the title of “Archbishop Leonty of Chile: Confessor of Heartfelt Orthodoxy” – this was all frighteningly interesting for a born-again “zarubezhnik [i.e., member of the Russian Church Abroad, lit. one who is beyond the border] from the USSR and I decided to dedicate my B.Th. thesis to a biography of Archbishop Leonty. Later I wrote to Fr. Herman, asking him to share documents. In answer, I received from him a request to provide him with my materials.

The next mediated encounter with Fr. Herman occurred in Alaska, in the summer of 2000, when I was looking for work on Kodiak Island during the salmon season. A priestless Old Believer, Petr Ivanovich Basargin, drove me to a boys’ school (academy) named in honor of St. Innocent. At that time clergy of “Fr. Herman’s jurisdiction” happened to be meeting to correct their canonical standing and join themselves to the Serbian or Bulgarian Orthodox Churches. In the school chapel, it was joyous to hear chants sung at Holy Trinity Monastery at small compline during veneration, only this time in English. And in this positive propagation of the tradition of Russian piety lies the service of Fr. Herman. In 2000 and then in 2001 I visited Fr. Herman’s skete on Spruce Island and the resident monks’ openness, hospitality, and simplicity made the most favorable impression on me.

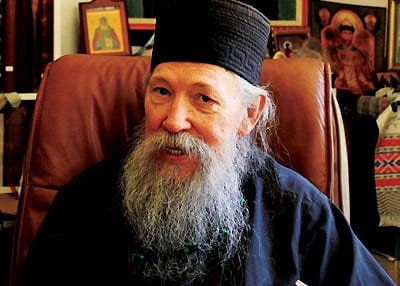

Attempts to obtain materials on Archbishop Leonty were renewed with the now-“canonical” abbot in Platina – Fr. Gerasim. Then suddenly, I don’t remember how the correspondence with Fr. Herman resumed. In September of 2012, I flew to Platina – it was the thirtieth anniversary of the repose of Fr. Seraphim (Rose); the festal services were led by our Metropolitan Hilarion and on the next day after his service in Platina, I arrived there in order to visit Fr. Herman. In Platina, I spent a day and a half, and during this time I had several meetings with Fr. Herman.

Fr. Herman’s openness and a rare mastery of the Russian language impressed me. He, like Metropolitan Vitaly (Oustunov), had a style, high diction, not just a vocabulary. Overall, there was the feeling that you had found some multi-faceted fragment from the old Russian Church Abroad.

In his Russkii Palomnik, Fr. Herman attempted to pursue the idea of “Independent Orthodox Workers” (IOW). In the end, this word “independent” brought Fr. German into conflict with his ruling Hierarch, Vladyka Archbishop Anthony, but part of this approach was also that Fr. Herman tried to openly speak about the history of ROCOR, albeit controversially and dissonantly, in this way drawing interest to the complex issues of our recent history. Nevertheless, such an approach was better than concealing problems for the sake of “esprit de corps”.

I am not Fr. Herman’s biographer and much less so his hagiographer. Suffice it to say that I know of the problems and accusations tied to his person. In my present portrait, I wanted to highlight the loyalty (albeit obscured) he carried throughout his life to the ideal of beauty, about which he speaks in his interview.

Upon returning from Platina I received a letter from Fr. Herman, in which he speaks of the influence Vladyka Leonty of Chile had on the future Frs. Herman and Seraphim, who supported their idea of self-reliant church activity – IOW. So it happens that within Fr. Herman’s approach was a certain tradition that had a place in the Russian Church Abroad. Clearly, this tradition was problematic, but its existence points out that the real historical situation seems more complicated than “a bad abbot” and “good defenders of the bishops”. We are all interconnected!

Deacon Andrei Psarev

When did you first come to Jordanville?

All my life I suffered from the absence of a father. I was in need of an authority figure. Mother was no authority figure. But she was of strong character; of course, she raised me in piety. But since I am from an artistic family, my soul was tied to art. I wanted to be a painter, I adored opera, I was very fond of literature, especially Russian – Pushkin, Lermontov. And my high school – it was a privileged school – was called “Music and Art”, and the students were divided into those who studied music and art. I studied art.

This was in New York, right?

Yes, in New York. One could apply there. This was a public [school], but to get in – there were special exams and so on. And so I spent lots of time in the museum. There are many museums, art museums, there in New York. And so, as it were, I created my own world. And I entered high school already with a formed understanding of what is beauty and what is truth. And in composition class the teacher, Mrs. Rozen, taught this idea that “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Meaning, beauty changes. One student says: “So if a cow goes and makes a pile? This can also be called beauty?” She says yes. And she opened to me this idea, which means that beauty doesn’t exist, it’s only a fantasy. She took from me the ideal of life. I’ll never forget: despondency reigned in my soul. And here I saw the movie Hamlet with Laurence Olivier. And when I exited the theater, I was a different person. The question of life was not so much negative as meaningless. At that time the idea of suicide didn’t exist. But I was extinguished. She, that Mrs. Rozen, right away knocked out of me the idea of beauty – that it was reality, and not just fantasy. Hamlet – this was the question, “to be or not to be”; but at that time I wasn’t thinking yet about suicide. But it came to that, because when I finished high school, I didn’t want to go to college, to learn, I didn’t want to live. There was no point. Literature, especially Russian, was for me a road, but it was from a dead world that no longer was. The world of Turgenev, Tolstoy…I understood Raskolnikov well. But I didn’t want to kill anyone, I figured that there is no God, not any more, they took him away; my god was art. I decided in front of a bridge…I was in Boston one day and decided to end my life. And when I stood on the bridge and thought to jump…Suddenly a thought, a bright thought, figuratively: in childhood I saw, I had a book of Sergius of Radonezh, with illustrations, in childhood – he is in the forest, with a bear, there the Mother of God is walking, an angel serves with him. And suddenly the thought – what if [I place my] hope on such a person as Sergius of Radonezh?…If you jump now, then you didn’t see him? Can it be?…I threw out the idea. And I started crying and walked home. On the way there was a symphony orchestra, Symphony Hall, in Boston. I look – there’s something there: some word with an M and two S’s. I don’t understand anything. But I was in a hurry, I wanted to go home, I had to turn onto this street. Suddenly one young man runs up to me, grabs my hand and shoves something in – apparently, he wanted to see me a ticket. But I couldn’t grasp what the deal was. And he then gestured with his hand, grabbed my hand and pulled me to the entrance. The usher was there. She grabbed my hand and pulled me into the hall. Then I understood, that it turns out he wanted to sell me the ticket, but seeing that I was crying he thought that I wanted it (laughs) and so he pulled me by the hand, let me to the entrance, tells her – says, go in. And she sat me in such … she sat me in the best spot, and at that moment Handel’s “Messiah” began. The music is unforgettable. After there was a formal presentation, in tail-coats, so elegant, and I’m in rags. And suddenly, when they sang “Alleluia”, everyone stood and sang. And it struck me [И мне открылось, lit. it was revealed to me] – God is beauty. Mrs. Rozen was wrong. And in this way I received faith. And I started seeking the idea of monasticism. So I went to the monastery…I knew a catholic monastery, but they did not comfort. I discovered that there exists a Russian monastery. And after several attempts I arrived. And I felt there, for some reason I felt, that Fr. Kyprian’s frescoes remind me of Giotto. I knew Giotto. And the music – “Boris Godunov”. And upon me the most powerful…I was reborn.

This was when you came to Jordanville?

The first time.

This was in ‘54, right?

Yes. And later only I met Fr. Constantine for the first time. He said: “We have a good bookshop, we can even send things by mail. Go meet the shopkeeper.” This was Fr. Vladimir. And he spoke with me with such love, and I understood, that beauty is divinity. And of course, here is Holy Russia. Boris Godunov! (laughs) And I had an epiphany. And everyone had a beard. Everyone was benevolent.

Toward you?

Yes, they answered all questions. At night Fr. Vladimir took me walking and opened up about himself. I talked about my life. And he promised to write me. And within me appeared not just joy in life – a meaning to life, through which I could attain to Christ. And facets of the other world were revealed to me: that there is a God, and that He is accessible. I was nineteen years old. I began coming [regularly], but before that Fr. Vladimir told me: “You are the worldly element. You need a priest in the world.” I say: “I don’t need anything, I received here everything that…” – “No, no, go to New York.” I say: “New York, again to New York? I don’t want New York.” – “No, you won’t regret it” and he directed me to Fr. Adrian [Rymarenko]. And he [Fr. Adrian] put in my head the correct way of life, and instead of reading spiritual literature he required that I read Russian literature from an Orthodox point of view. This is very important. The majority now doesn’t read Russian literature, doesn’t realize that it is a product of Holy Russia. People lived this way, and in Fr. Adrian’s cell there were portraits of elders. And right away he told me about Fr. Nektarii [of Optina] and later he described to me how he saw light coming out of Fr. Nektarii. That, which was needed, I received: in Jordanville they returned beauty and love to life; while, as Fr. Constantine said, Fr. Adrian “groomed my mind”.

Was it difficult for you to live there in Jordanville when you were a seminarian?

No, no. On the contrary, I was attached to it. But I strongly judged the students, the seminarians.

What did you judge them for?

Because they had their own fathers, they put down roots in America, they smoked – they would smoke from time to time, they thought about girls who could become matushki, in essence they were not spiritual at all, except Fr. Ioann Milander, who….My friend Igor, he came out of a Puerto Rican ghetto. Before he came to Jordanville he used to occupy himself with smoking, etc. So I…I had only one friend, that was Volodia Popov, remember him? Volodia Popov?

He was a protodeacon later in Connecticut.

Yes. And he was my friend. But the whole atmosphere of Jordanville, this was remarkable. I lived in my world – the Church. I even enjoyed the cow barn. Because it reminded me of Tolstoy.

And with whom did you associate among the monks?

Mainly, with Fr. Vladimir.

Mostly with Fr. Vladimir?

Yes. My spiritual father was Fr. Antonii at first. Then later, Fr. Constantine.

How was it for you with Fr. Kyprian?

I painted icons with him. Fr. Kyprian, his reputation was of a “tough guy”. Our guys called him “Private [unintelligible] Police”.

What was that?

“Private [unintelligible] Police”. Everyone feared him. He had no time for me.

So, did you associate with Fr. Laurus?

Yes, he was my boss. My obedience was in the office – there were three desks: Fr. Laurus in the corner, the next table was Fr. Vladimir, and mine in the middle. Then, Fr. Sergei was very dear to me.

So you had contact with him too?

Yes. I would take walks with him. Then, there was this Fr. Herman – old, from Valaam.

A monk, yes?

Yes, of course. Averkii was very close. Always, when I wanted to speak to him, always…especially to me he…he treated me very well. And the seminarians joked that he found in me an intellectual. Everything was disrespect [unintelligible].

But with Vladyka Averkii, was it at all boring? It seems to me that…when one looks at his sermons, that they are so long, and it seems to me he’s the kind of person around whom one is altogether shy – I feel this way. I would feel this way with him.

No, I didn’t have this.

Really?

I revered him. He was so noble. Then…he always addressed me formally [«на Вы»] (laughs). I was flattered [unintelligible].

Well, sure.

Then there was Fr. Nikodim, from Latvia, my…

…compatriot.

Yes. And when I first came, I slept in his cell. He was this prayerful man.

I knew his sister.

Yes, I knew her, too. What was her name?

She was Ludmilla.

That’s right. I knew her husband, too.

Yes. She died in Jerusalem. She was tonsured into the riassa as Nun Ioanna.

Yes, in honor of [New Hieromartyr John] Pommers. Then, Nikolai Nikolaevich treated me very well.

Aleksandrov, yes?

Yes. [unintelligible] undeservedly.

And who do you remember from the faculty?

Oh, I loved them very much. First of all, my neighbor Nikolai Dmitrievich Talberg. I brought food to him. He even cried, when I made it. [unintelligible] He was very kind. Together we revered [Emperor] Paul I. And Alexander I (Feodor Kuzmich). And then my most favorite professor was Andreev. I adored this person.

Andreev?

Yes. Adored. First of all, he was learned, approachable, passionate – and he adored music. I even got for him a record of Rimsky Korsakov’s “Mozart and Salieri”. And we was so thankful to me. And when it was time to write a dissertation, I wrote for him on Tikhon of Zadonsk. But unfortunately I only finished one part. I wanted a second part about the saint’s disciples. But I didn’t finish. Right after finishing seminary I went to Alaska.

But that means you decided not to enter Jordanville, there? To stay as a novice and so forth?

No, I wanted to know what I should do. Because this thought came to me, that I, if I am to be a pastor, then I will come across people, who have been raised by Mrs. Rozen. In high school there was another one – Mrs. Shapiro. One time I had to give a little presentation. I chose the topic of Marx and said derisively: “He is the cause of all my misfortunes.” And their class ended, and she says: “Let’s go to my office.” She closed the door and said: “Never dare saying anything negative about Marx and Lenin. They are benefactors of mankind.” I said: “Thank you,” I understood – she fits with Mrs. Rozen. Because if you take away the idea of truth and beauty, then of course Lenin is a hero. But in my understanding he is a beast. And so, when I finished seminary, I needed to find out what I should do. I liked….I had a girl there, I was in love… [unintelligible] She didn’t believe in God – what kind of matushka…? (laughs) I needed to…I decided quite providentially, I learned that in Alaska there lived a hermit [Fr. Gerasim Shmaltz], and Fr. Vladimir gave me his address. They in correspondence. I inherited his letters. And I wrote: “I want to visit you, dear [unintelligible] father.” And I decided then and there to seek an answer. And so then I went. So then – I counted it unworthy of being called a pilgrim to ride in comfortable automobiles, trains, or planes. In Russia they went on foot. Of course, here in America you won’t get there on foot without an automobile. What to do? I decided [unintelligible] to get to Alaska without money in my pocket. Only a little video projector…My friend Fr. Roman Lukianov game me recordings, thirty three pieces. I would stop on the way, with Vl. Averky’s blessing, at our parishes, if they gave money then I needed to go further. And so I was in Detroit, Cleveland and so on. And when my mother learned about this idea, without money, she was scared and started sending money. I protested, but then I put it in the wallet and closed it (laughs). So you are on the right path. [unintelligible] To Los Angeles. And Vladyka Antony [Sinkevitch] there. I asked to speak on Sunday but he says: “You’re not going to tell me my schedule. You’ll speak on Tuesday at 7 pm, and that’s enough!” Well, what could I do? But there…do you know Irochka Lukianov? Fr. Roman?

Yes, I knew her.

The dad lived there, her dad. He says: “He’s a despot, you can’t argue, be quiet.” I was obedient and I came to this despot on Tuesday and I look – some kind of celebration, a mass of overdressed girls, flowers…turns out, he set these girls up for me [to choose] my bride. (laughs)

You see how…that’s also good, right?

And he gave a check for $250. So they paid for my flight to Spruce Island and back. And there, on Spruce Islandi, [unintelligible], and I had an epiphany. That’s already another story.

You caught the time, when there were churchly people – such as Kontsevich, the Makushinsy’s – a whole slew of these people who lived by the Church…and so what other families were there of such people, who like this fully lived by the Church? Like Kontsevich…and who else was there from these church people?

After seminary?

Well, at that time, and during seminary, and in general?

After seminary, I went to Monterey. And taught the Russian language. Five years. And there were colleagues – Russians, intelligentsia. Valuable people, many from the Soviet Union, they knew the catacombs, they knew martyrs. I wrote it down. And thus in the book, Russian Catacomb Saints, this is almost all that, which I wrote down [unintelligible] because they spoke of what they knew. And from them I received confirmation of what I heard in Jordanville: we had real martyrs. Fr. Gelasii, a hierodeacon. He argued with Fr. Kyprian and right away dug himself a ditch in the garden and lived there as an ill man. And the injuries on his spine didn’t heal from when the communists beat him. He was a member of the Catacomb Church. Such was Fr. Nektarii, who was a member of the Catacomb Church, the organized one. Fr. Adrian reckoned that there couldn’t be a Catacomb Church in Russia, but Andreev debated him. They had an argument. And [Vladyka] Leontii also reckoned, that there was too great a persecution. But Andreev, he was on Solovki, and later he lived in Petersburg, and under the Germans, he ended up on the German side [i.e. in occupied territory]. He was in Gatchina. And in this way, the Germans picked him up. And he maintained contact. So I had acquaintances, who were living representatives of the persecuted church. And Fr. Nektarii also had injuries that didn’t heal. And when I told all this to Fr. Seraphim [Rose], he was in shock, that it was alive…There was also Fr. Iov, [unintelligible] for example. He was, when the Soviet citizens were sent back by the allies – you know this, right? Fr. Roman wrote to me.

After seminary, I went to Monterey. And taught the Russian language. Five years. And there were colleagues – Russians, intelligentsia. Valuable people, many from the Soviet Union, they knew the catacombs, they knew martyrs. I wrote it down. And thus in the book, Russian Catacomb Saints, this is almost all that, which I wrote down [unintelligible] because they spoke of what they knew. And from them I received confirmation of what I heard in Jordanville: we had real martyrs. Fr. Gelasii, a hierodeacon. He argued with Fr. Kyprian and right away dug himself a ditch in the garden and lived there as an ill man. And the injuries on his spine didn’t heal from when the communists beat him. He was a member of the Catacomb Church. Such was Fr. Nektarii, who was a member of the Catacomb Church, the organized one. Fr. Adrian reckoned that there couldn’t be a Catacomb Church in Russia, but Andreev debated him. They had an argument. And [Vladyka] Leontii also reckoned, that there was too great a persecution. But Andreev, he was on Solovki, and later he lived in Petersburg, and under the Germans, he ended up on the German side [i.e. in occupied territory]. He was in Gatchina. And in this way, the Germans picked him up. And he maintained contact. So I had acquaintances, who were living representatives of the persecuted church. And Fr. Nektarii also had injuries that didn’t heal. And when I told all this to Fr. Seraphim [Rose], he was in shock, that it was alive…There was also Fr. Iov, [unintelligible] for example. He was, when the Soviet citizens were sent back by the allies – you know this, right? Fr. Roman wrote to me.

Fr. Roman Lukianov?

Yes. His wife Irochka was there too, when they sent them back…they threw people into the cart.

This was in Lientz, then, you mean?

Yes [in fact it was in Kemptten]. So this affected me greatly, and I was able to transmit this…He [Andreev] reckoned that the most important thing that he did was to give this to me. We credited this to Andreev, the first part is his memories. The rest is all ours.

So the first part is his, yes? The translation? Andreev’s? His writings, right, in the first part?

Fully. And then mine and Fr. Seraphim…he did something important there.

Well, it became a bestseller, they sold out a long time ago, and in general it was a very popular book.

There wasn’t even a thousand.

They printed less than a thousand?

Yes. And sixteen are left here. This was the last thing he [Fr. Seraphim Rose] wrote before he died. And I finished it. Rather, he did it all…everything was finish, I only added from memory. Americans don’t understand this. Fr. Seraphim understood, but all these…they’re too well off for their own good [с жиру бесятся, lit. rage with fat]. You know – the good life, sports, money, automobiles…

But the soul still searches for something, the soul isn’t satisfied with this, I think, people somehow…somehow people still search, search, even with all this.

We were all afraid, Fr. Seraphim was also afraid, that a movement would start, he would say – catacombs on the full stomach. They say these acquaintances ride around in cars, eat hamburgers. And this is different psychology.

Yes, this is exactly what we were saying – namely, there is no longer this Catacomb Church, because the circumstances have completely changed; this is already people mimicking something…

Something else interesting – we didn’t want to be monks, we didn’t leave the world, but we wanted to live like monks. We wanted [to live] like elders and desert-dwellers and because of this we didn’t accept ordination and monasticism. But on Pascha we drove to the Lophushinskii’s in Sacramento, there was this priest there – Fr. Grigorii Tanasiuk. His matushka was this buxom [lady]. We communed with Lopushinskii and met Pascha. Rather, not Pascha but Great Thursday. Then we returned and met Pascha on the mountain. And we set a table and also sat Fr. Michael.

Rozhdestvenskii, right? They set it, right?

No we set it. We met Pascha at the double. And it was the most remarkable story. The Paschal quiet, grace. So I [unintelligible] Fr. Herman in Alaska. I lived with him for a week, more than a week. He wrote a stack. Probably a hundred letters, besides one letter to Fr. Konstantin. Fr. Vladimir sent me a xerox copy, because the original was in the archive.

[…]

They [the seminarians] judged Fr. Konstantin (Zaitsev) harshly for his language [difficult style of exposition], but it appealed to me.

Yes?

Everything appealed to me. This was Russian intelligentsia, subtle, a connoisseur of Chopin. He came to the seminary dorm every morning and prayers were read there, and then we went to breakfast… But the most [unintelligible] was Fr. Vitalii. Every morning he spoke about the antichrist. (laughs)

Well yeah. Probably, people already – the seminarians didn’t take this all very seriously, right?

…Of course. Without a doubt. This was his favorite hobby horse. And Fr. Feodor (Gofeints)?

Yes, I’ve heard of him, he was a Rassaphore, right?

No, he was a monk. His father was there too. He was with Vladyka Ioann Rizhskii, not with that one, not the martyr.

Garklavs?

Yes. That was my bishop. I greatly revere the icon of the Tikhvin Mother of God. We were in seminary, I drove to venerate her and receive a blessing for [my trip to] Alaska. I venerated the icon and he blessed me. Then later, when Fr. Seraphim and I founded the bookstore, Vladyka Ioann [Garklavs] himself came with the icon, he brought the icon for a cross procession, and he appeared on purpose, with my own hands I carried the icon and made the sign of the cross on all four sides. So the store….and I touched the wall – the Tikhvin Mother of God touched the wall of the building. But we didn’t take her into the cathedral – “a different jurisdiction!” And later I say to Vladyka Antonii: “Vladyka, look, the icon is with us.” And we drove it to the St. Tikhon of Zadonsk orphanage, and later I went to Tikhvin twice: before her [the icon’s] return and after. This is my icon. She was in Riga. I remember as a boy, in ‘44…mama woke us up: “Quickly to meet icon”…we met her….I remember…Then later she left to Germany, and then to Chicago. I had such a time – we … my grandma was in America and when we came, we lived with grandma. And she was a drunkard. She was a prima-ballerina in Riga…She came to America old, opened her own studio and drank. It was hard. We moved out and rented a separate apartment in a bad area. And suddenly mama fell ill. She fell ill and took to her bed. This was already the beginning of the end. I was sixteen years old. There was no father….and our acquaintances took her to Boston. But I stayed alone to finish high school. In this moment of such despair and loneliness I was starving. And one day I reached…despair and suddently someone said, that the Tikhvin Mother of God is in New York. Right away I sat on the subway and got there. From then on…I’m bound. First she was in New York, then Chicago.

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev. Translated from Russian by Deacon Peter Markevich

[…] Monk Herman (Podmoshenskii), Platina, California, September 4, 2012 (an interview conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev) […]