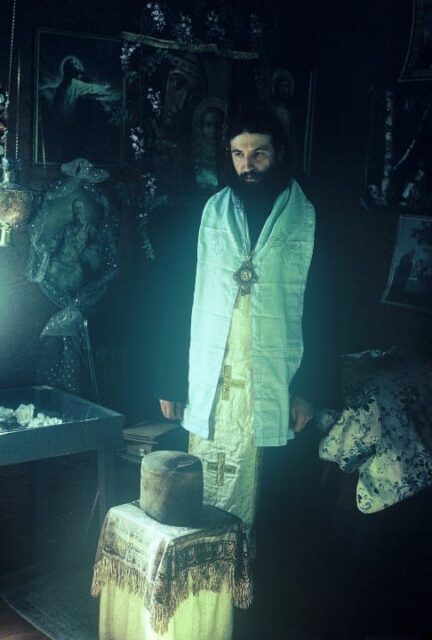

March 16, 2013 marks the 5th anniversary of the passing of His Eminence Vladyka Metropolitan Laurus. In order to observe this event and to refresh our memory of Vladyka, Orthodox Life spoke with Protodeacon Victor Lochmatow, who was the cell keeper, secretary, driver, deacon and close assistant of this most wonderful bishop for nearly 50 years.

Fr. Victor, of those of us still living, you knew his Eminence Vladyka Metropolitan Laurus the longest When did you first meet Vladyka.

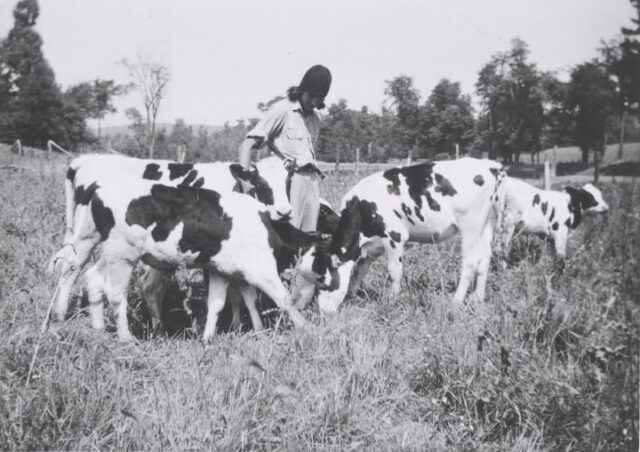

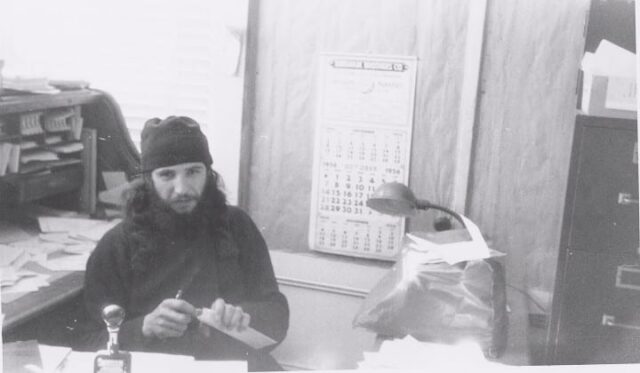

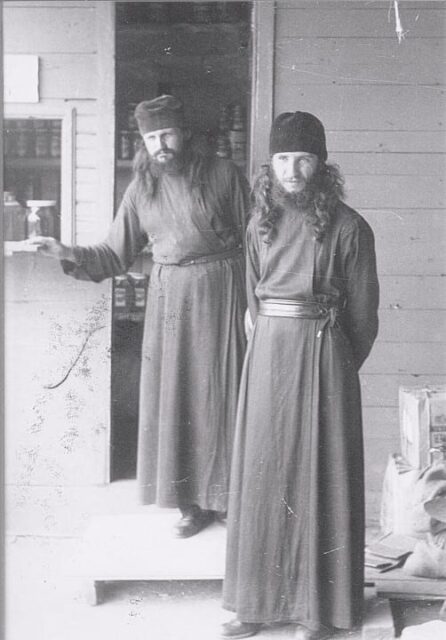

We first met in 1957.1 was 11 or 12 years old then. I had heard about Holy Trinity Monastery from a young man who had spent some time there the year before. He had told me about the farm which fed the monks, about the tractors and machinery. This caught my interest, so I asked Vladyka Gregory, (Archbishop of Chicago at that time), to write to Fr. Cyprian (Pyzhov), of the monastery, for permission for me to visit. This he did, and soon we received a letter from Fr. Cyprian, dean of the monastery [and famous iconographer – Ed.], allowing me to come. I arrived alone by train from Chicago on the New York Central Railroad. Herkimer had a train station at the time. I remember being picked up by Fr. Flor (Vanko) and brought into the monastery church on Sunday morning. I was met by Fr. Cyprian, who asked me if I was from Chicago. He immediately made me feel welcome. At that time the only available sleeping quarters were in what is currently our seminary dormitory. The main building, which now houses the cells of the monks was nearing completion, but not quite ready. Lodging was assigned for me in a small room which I shared with a young 29 year old hieromonk, who turned out to be the future Vladyka Laurus. So my immersion into the life of the monastery was concurrent with my getting to know and growing close to Vladyka.

Is there anything that stands out in your mind from those early days?

From the very beginning what impressed me most was that everyone was doing something, everybody was working, all were busy and I did not see any bosses around anywhere. The dedication, the zeal of the brotherhood was amazing. Everybody just did what needed to be done. For example, here is an early memory from my very first days at the monastery:

On the very next day following my arrival, after the early morning Liturgy, I decided to take a walk around the monastery property. I noticed that the hill (which later was to become the monastery cemetery) was being ploughed by a monk whose name I later found out to be Fr. Varlaam. Oats were later planted on that field. While crossing that area I came upon a poorly clothed elderly man who was collecting stones and boulders churned up by the plough. He was loading them up into an old red pickup truck. When he saw me he turned to me and said: “go to the barn and bring me a lorn – a crowbar.” At that time I did not even know what a lorn was, but I went back to the monastery and someone helped me find a big old crowbar, which I lugged back to the old man in the field. A day or two later I saw that same elderly man again. This time it was in church. He was standing in the Altar in front of the Holy Table, vested, with a miter on his head, leading the service. I was shocked. This raggedy old man from the field was Fr. Panteleimon, founder of the monastery.

I especially liked working with Fr. Flor. He was in charge of the tractors and other equipment. At that time, as a twelve year old, that is what interested me most. After some training, Fr. Flor gave me permission to drive the machinery on the property of the monastery farm. This was when I met some of the other young men who were spending their summer vacation at the monastery. These were mostly sons of families from our parish in Albany, NY. We became friends and decided all together that we would go home to get our warm clothes and convince our parents to allow us to spend the winter at the monastery. Well, as it turned out, I was the only one that ended up doing this. The monastic Fathers arranged for me to attend school in Van Hornesville, the closest village to the monastery with a school. Meanwhile, back at the monastery, Fathers Laurus and Flor taught me Law of God and to read Church Slavonic.

You often accompanied Vladyka on his travels to the Holy Land, Mount Athos and other holy places. Please recall any special occurrences during these pilgrimages.

Our very first trip took place in 1964. We traveled to the Holy Land by way of Rome, Germany, Greece, Mount Athos, Turkey, and Jordan (where we spent an entire month on the West Bank) the Sinai and Egypt. This trip also included Vladyka’s first return to his homeland in Czechoslovakia, where he visited his family. We spent the entire summer traveling.

Especially memorable from this trip was visiting with the monks of Karulya on Mount Athos, where the monks had to climb up the side of the mountain using chains in order to get to their cells. This was spectacular. Our ascent of Mount Sinai in Egypt was just as spectacular. We started at 3:00 a.m. in the dark and climbed all morning to get to the church built on the top of the mountain. This church stands on the very place where Moses had received the Commandments. The Divine Liturgy was being served there that day.

When traveling with Vladyka Laurus, you were never a tourist. You were on a pilgrimage. His only interests were churches, holy relics, sacred sites and the like. These were places familiar to him, for he had read about them extensively ahead of time. Also, he would befriend and correspond with the keepers of these sites. Because of this, many places that perhaps were inaccessible to others were always open to Vladyka. All doors were open to him and I was fortunate to be with him at the time.

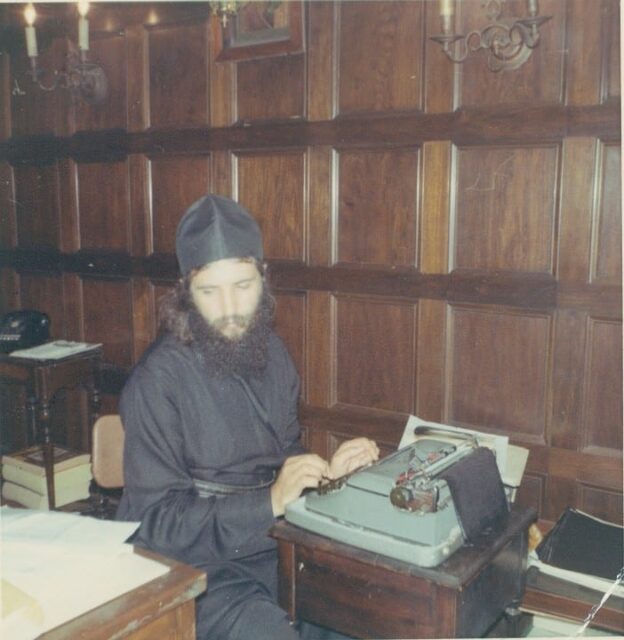

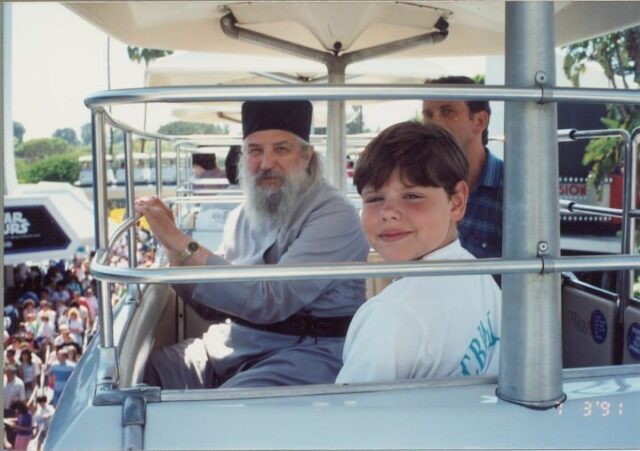

Another aspect of Vladyka’s travels was that he liked to travel incognito, especially when he became a bishop. His interest was not to be recognized and honored, but just to travel and study the faith of the people, to see the situation as it really was: especially in Russia. During the 90s, while still an Archbishop, [he was elected Metropolitan in the year 2000 – Ed.] Vladyka traveled to Russia secretly several times. Dressed as a simple hieromonk, he would quietly visit various monasteries and churches. His constant warning to me was: “Don’t you dare call me ‘Vladyka!'” He was very observant. Back at home in our Monastery he would notice much more than he let on. The same held true about his trips to Russia. He was alert to everything, noticed everything, especially the life of the Orthodox faithful. This eventually convinced him that the division [of the Russian Church Outside Russia and the Church in Russia – Ed.] must be ended.

One such incognito trip was especially poignant. In 1991 the relics of St. Seraphim of Sarov were identified and festively translated to their rightful place in Diveyevo Convent. Certain “elements” of the Church Abroad had come out with statements calling the relics “fake” and the Russian Church “graceless.” Though disagreeing vehemently in private, Vladyka Laurus did not engage these accusatory statements publicly. He simply traveled to Diveyevo and served a moleben before the relics of St. Seraphim. Though he had traveled anonymously, his actions become known and all the negative statements about the relics disappeared.

In your years as a seminarian at Holy Trinity Seminary, Vladyka had a special relationship with you and your entire seminary class. Can you please describe his role in your seminary education?

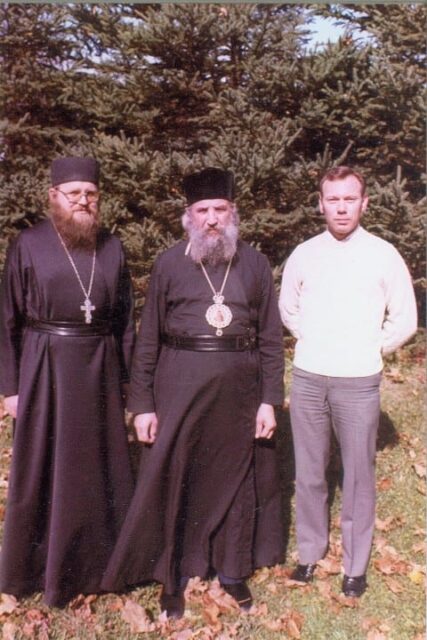

This question can best be answered by quoting the dedication from the retrospective album, which our seminary class put together to honor Vladyka Laurus’ 20th Episcopal anniversary in 1987. On the day of the celebration of the anniversary, after thanksgiving services at the Monastery, everyone was invited for a banquet and concert in honor of Vladyka at the local community college in Herkimer. Metropolitan Vitaly and many other bishops, clergy and laity attended. Mstislav Rostropovich (cellist) gave a benefit concert. After a plentiful banquet, Vadika was presented with keys to a new car, purchased for funds which our class had collected from those many individuals around the world who respected and loved him. Each banquet participant received a commemorative album. Its dedication answers your question so concisely:

On the path of life everyone encounters personalities whose influence thereafter is felt until one’s death. The memory of them is indelible, just as it is impossible to forget father or mother. Just such a personality was revealed to us, the 1967 graduates of Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville, in Vladyka Laurus, at that time an Archimandrite, Inspector of the Seminary [in current language — “dean of students” — Ed.] In gratitude to our spiritual leader, teacher and Fr., for all the love he has shown to us, we dedicate this memorial album and have arranged this celebration to honor him in this 20th year of his service to the Holy Orthodox Church as a bishop

Though very personable and loved by most laymen outside the Monastery, Vladyka is often described as being “a real monk.” Though not a monastic yourself, you witnessed the life of Vladyka as a monk. Please relate any special memories you have of Vladyka as a monastic.

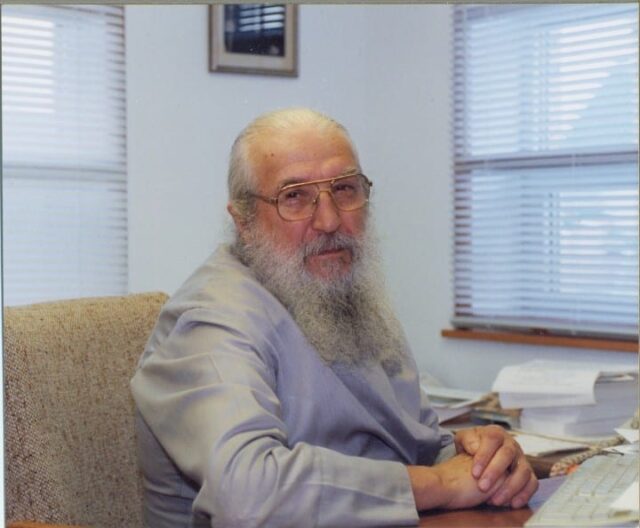

I believe that he fulfilled his monastic obediences beyond any reproach. Even as a bishop, first and foremost, he was truly a monk. During trips or at home, he always refused any conveniences I would offer him. When we traveled, no matter how early in the morning or late at night, he would fulfill the monastic rule. At the beginning he would have someone read or read it himself. Later, when tapes and disks became available, we would listen as we drove. Sometimes, when we were reaching our destination and the prayers had not been completed, Vladyka would have me make a detour so that we could finish the prayers. As abbot and bishop, although often ill, he always led the brotherhood and his flock by example. No matter how late we had returned from some meeting of the Synod of Bishops in New York City, he would be up at 4:30 in the morning for the monastic Midnight Office. If at all possible, he never missed any meals with the brotherhood in the refectory, considering this to be a vital component of fellowship with his monastic family.

The greatest example of this leading by example came at the very end of his life. Great Lent was just about to begin. As is known, the brotherhood spends almost the entire week in church from early morning to late in the evening. The continual prayers are periodically interrupted by assigned readings from the Holy Fathers. In the evening during the Compline service, the lengthy Repentance Canon of St. Andrew of Crete is read. Though he had already turned 80 and had just returned from an extremely grueling trip to Russia, Vladyka not only came to all the services of the first week of Lent, but, as the head of the community, he fulfilled his duty by doing all the readings himself as he had always done before.

I am aware that from his early days as a boy in Ladomirova, at the age of 8 or 9, shortly after his mother’s untimely death, he began asking permission to become a monastic. Finally he was allowed to enter the monastery at the age of 11. In 1944, at the age of 16, he became a novice. One seminarian related the following to me. This was a candidate for the priesthood and had stopped shaving to grow a beard for the first time. His face was itching terribly and he had asked Vladyka when the itching would stop. (This is the type of thing people were comfortable asking the Archbishop because of his extreme accessibility). To the seminarian’s surprise, Vladyka answered: “I have no idea. I have never shaved in my life.” He had entered the monastery before a need to shave had arisen.

Once he confided to me a desire that he had throughout his lifetime: when he became older, he wished to go to Mount Athos and finish out his life as a simple Athonite monk. That obviously was not the will of God. He was made Metropolitan and played a pivotal role in the history of the Russian Church.

Please describe what many call “his special approach,” i.e. his patience and long-suffering as abbot of Holy Trinity Monastery and as a Bishop.

When you did something wrong, Vladyka would actually treat you with even more love. He would talk to you in a way that did not mock you or even scold you. He would just talk to you in a loving way. Only after you had left his presence would you realize that you had been reprimanded. This loving approach made it highly unlikely that you would ever repeat that mistake again. You just did not want to disappoint your loving Father. This was just one of the many gifts he had in dealing with those for whom he was responsible.

Our current abbot, Archimandrite Luke, recently recalled that whenever someone came to Vladyka with a complaint, or with some idea, whether good or harebrained, he would never act quickly or rashly. He would wait a while, be it hours, days or weeks and then make a decision, take action. His mode of operation was always “little by little” and “no extremes.” He would express this in Greek, “siga, siga”!

Vladyka Laurus was one of the youngest to become a bishop. He would later become an Archbishop and finally Metropolitan and First-Hierarch of the Russian Church Outside of Russia. It was under his leadership that the Russian Church outside of Russia reestablished canonical communion with the Church in Russia. Perhaps an entire book may someday be written about all that Vladyka had to endure during that most complicated process of reunification. Is there anything that especially stands out in your mind about this very difficult period?

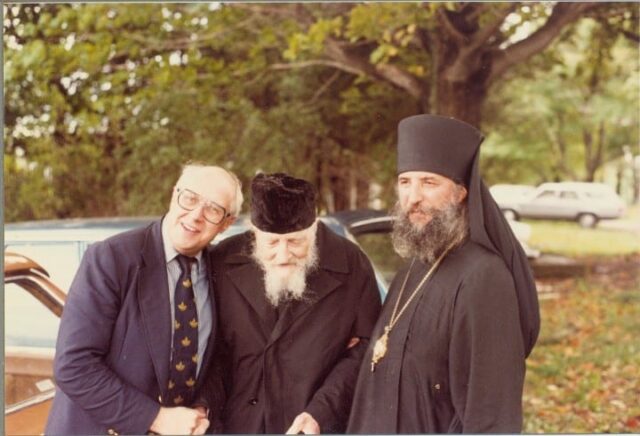

Vladyka never forced the issue. He often mentioned that his main desire for the mutual recognition with the Moscow Patriarchate was to have the opportunity to commune from the same chalice: not only for himself, but for all Russian Orthodox Christians. But in his wisdom, he knew that this desire could not be forced on others. He would gently suggest, but one had to come to the conclusion on one’s own. It is by his humility that he led the Russian Church Outside of RussiaI spoke earlier about the many pilgrimages which Vladyka undertook during which I had the honor to accompany him. One such trip was to the Pochaev Lavra [Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine -Ed.]. For Vladyka Laurus to visit Pochaev for the first time was like coming home. His spiritual mentor, Archbishop Vitaly (Maximenko), was from this monastery. Of course Vladyka Vitaly was long gone from Pochaev. But God provided a new Pochaev connection. One of the monks of contemporary Pochaev, Onuphry, rose to the rank of Metropolitan of Chernovtsi. Somehow early on Vladyka Laurus had begun a correspondence with him which lasted for many years. Then, long before the process of reunification started in earnest, an opportunity arose for the two bishops to meet. Vladyka Onuphry was traveling in Canada. A meeting was arranged near the border in a hotel in Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario. The initial encounter was very warm, filled with love. Then the bishops moved on for a one-on-one conversation in the library of the Hotel. This talk lasted for two to three hours.

Now Vladyka Laurus had the custom of never revealing what had gone on in meetings. Whether it was a meeting of the Synod of Bishops or business with some dignitary, we would get into the car: Vladyka would close his eyes and start praying on his chotki [prayer rope]. Very rarely, if ever, would he comment on what had transpired. After the meeting with Metropolitan Onuphry he said: “Yes, we have our problems, as well.” Perhaps this meeting, which occurred long before any official negotiations began, laid the foundation of the success that would later, with God’s help, lead to the reunification of the Russian Church.

I have to admit that initially, I had very little interest in any kind of canonical communion with the Moscow Patriarchate. I had grown up surrounded by the mentality that everything was red and white. I remembered how my diocesan bishop in Chicago had forbidden me to serve at the altar because I worked part-time in a bookstore where books from the USSR were being sold. These, after all, were our so-called “dreaded enemies,” and I was selling their books. I had to quit my job in that store in order to continue serving in the altar. Personally, I felt an immediate liking for Viadyka Onuphry; for me, he was a second Vladyka Laurus. But even after the meeting with Vladyka Onuphry, I was not “gung ho” for unification. Not knowing very much about the situation, I had my reservations. I became a convert for unification after our trip to Pochaev in 2003. From Pochaev we drove down to Ternopil, where we met Metropolitan Sergey and then to Chernovtsi, the domain of Vladyka Onuphry. We were amazed by the rebirth of Orthodox monasticism and parish life in and around Chernovtsi. This was all due to Metropolitan Onuphry’s efforts: monasteries and churches springing up like mushrooms after a warm autumn rain. We visited an orphanage that currently houses over 200 children, many of whom are disabled with various deformities because of the close proximity of Chernobyl. The moment we arrived, those children who could run out in one big crowd and mobbed Vladyka Onuphry, hugging and kissing him. We could not hold back our tears at this touching sight. Without any government assistance, this orphanage continues to grow and lovingly nurture, clothe, feed, heal and teach these children (Last year His Holiness Patriarch Kiril visited this orphanage and had nothing but the highest praise for the nuns and caretakers).

Seeing all this, I thought to myself: “What am I doing, sitting in the USA, judging these people as though they are not Orthodox enough for me… My attitude changed 180 degrees. I thought to myself; “I want to be like them”! And I became a convert, a proponent for unification.

Vladyka was a very strong and important influence in your life to his very end How, dear Fr. Victor, have you coped with your loss since he passed away?

It has been very difficult. Whenever I have come up against a problem, I think to myself: “What would Vladyka have me do in this situation? He had the knack of simultaneously being your greatest earthly authority and a simple friend. One could go to him with the most mundane problems or with the most profound spiritual questions. At times he could advise what to do. Being human, he did not always have an answer. But you always felt his empathy, his support. And he would always point you in the right direction, where you would find a resolution to your quandary.

I think that we can best summarize all that has been said by quoting a paragraph from the epistle on the occasion of the passing, funeral and burial of Metropolitan Laurus by His Holiness Patriarch Alexey:

The spiritual beauty of the personality of Metropolitan Laurus was especially revealed in personal contact with him. Because of his inherent deep Christian humility he never openly strove to demonstrate the many gifts granted to him by the Lord. Among these many gifts was unwavering dedication to his archpastoral calling and the monastic path. Along with this he had a deep, genuine faith: a faith by which spiritual strugglers of the past wrought righteousness, obtained promises (Hebrews 11:33). Thanks to this steadfast faith, Vladyka Metropolitan was able to guide the flock entrusted to him to a newly found spiritual union with their Fatherland, with a Rus’ being reborn after grievous years of atheism.

We pray for the newly-departed Vladyka Laurus that he find rest in a place “where the righteous dwell.” May his memory be eternal!

With love in the Lord, +Alexey, Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus’

Conducted on March 5, 2013 by Archpriest Gregory Naumenko, Orthodox Life, no. 2, 2013