From the Author

This article was written in response to the transfer of ROCOR property in Hebron (1997) and Jericho (2000) to the Russian Orthodox Church (MP) by the Palestinian Authority. It was published in Pravoslavnaia Rus’ [Orthodox Russia] No. 18 (September 15/28, 2000). Despite its apologetic thrust, inadequate citing of sources, “biased” vocabulary, and propagandistic character, one can derive value from the article as an attempt to get a feel for the pastoral aspect of what it means to exist canonically in the modern circumstances. The article has been posted here without any revisions and is a further elaboration of the topic of the possibility of interrelations between the ROCOR and the Church within Russia during the interwar period, which was raised in my articles on Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhny Novgorod as Deputy Patriarchal locum tenens to Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy, and on the historical context for the adoption of Patriarch Tikhon’s Decree of May 5, 1922 dissolving the Supreme Church Governance Abroad. This translation has been made possible by a grant from the American Russian Aid Association – Otrada, Inc.

The Church at Home and Abroad: Responsibility of its Foreign Part in Preserving Property

It was not in 1920, but at the beginning of the Russian Civil War that part of the Russian Orthodox Church ended up abroad, when the front dividing White and Red Russia effectively served as the national border. For instance, newspapers published in the territories free from Bolshevik control were termed “foreign” in Soviet usage. The Supreme Church Governance of the Church Abroad, which preceded the still-extant Synod of Bishops, is in its turn descended from the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority in the South East of Russia; this was a church governing body to which all bishops in that area were subject. It was this Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority that convened a Council in Stavropol gathering in 1919 together all the bishops from the South of Russia, which was free from Bolshevik control. In an article dedicated to the 20th anniversary of Decree (Ukase) No. 362, Ekustodian I. Makharoblidze, the head of the chancellery of the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Church Abroad in Belgrade, wrote that this decree, which provided the formal foundation for the legal basis of the ROCA, had been forwarded to him by one his colleagues from the Supreme Church Governance for the South East of Russia. In a supplementary letter, this former colleague of Makharoblidze’s wrote to the latter that “under the conditions in which the Patriarch and his Supreme Ecclesiastical Council are threatened with having their operations curtailed, His Holiness was very concerned to regulate the question of church governance; in the matter at hand, the basis for the November decree [Decree No. 362 was adopted on October 7/20, 1920] was the example of the Stavropol Council and its Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority.”[1]E. I. Makharoblidze, “20-letie rossiiskoi tserkovnoi “konstitutsii”” [“The 20th Anniversary of the ‘Constitution’ of the Russian Church”], in: Pravoslavnoe obozrenie … Continue reading After the Russian Army had left the Crimea, His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon recognized all the episcopal consecrations that had been performed at the behest of the Supreme Church Governance for the South East of Russia along with other decisions of the same.

When parts of General Wrangel’s Russian Army left their homeland, they regarded this as a temporary measure, as a retreat during an ongoing military operation. Most of those who left their homeland had no choice. They did not recognize the Soviet regime and therefore could not remain subject to it. The senior ranks of the army wanted to preserve their military organization in order to continue their struggle against the subjugators of Russia. Those officers who remained in Crimea out of a belief in the “nobility” of Lenin, Trotsky, and Co., were executed. What has been said here about the South of Russia could in principle be applied to the Far East and other regions of the Russian Empire through which Orthodox Christians were evacuated or fled from the Bolsheviks.

Thus, with regard to the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Church Abroad formed in 1920, His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon continued the same policy as with regard to the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority for the South East of Russia. One of a whole array of examples confirming this is the matter of the appointment of Archbishop Evlogii of Volyn’. At the time when there was still a Supreme Church Ecclesiastical Authority in Russia itself, Archbishop Evlogii had been appointed by it as an administrator of the churches in Western Europe, which were under the authority of the Metropolitan of Petrograd. This appointment had been made at the request of Archbishop Evlogii himself and submitted to the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority through Archbishop Dimitri (Abashidze) of Tavria. The rector of the church in Paris, Archpriest Ioann Smirnov, expressed a desire to have this appointment confirmed by the central Russian authorities. Decree No. 242 of March 27/April 9, 1921, issued by Patriarch Tikhon, the Synod, and the Supreme Church Council, was received through the intermediary of Archbishop Seraphim of Finland. The Decree reads as follows:

“To His Eminence Seraphim, Archbishop of Finland and Vyborg. With the blessing of His Holiness the Patriarch, the Holy Synod and the Supreme Church Council have heard in a joint session: the letter of Your Eminence of March 5 of this year, on the subject of the resolution of the Supreme Church Governance Abroad on the appointment of His Eminence Evlogii of Volyn’ as the administrator of the Russian churches in Western Europe, with the rights of a diocesan bishop.

“It was resolved,

in light of the resolution of the Supreme Church Governance of the Church Abroad [my emphasis —A.P.], to deem all Orthodox Russian churches in Western Europe to be temporarily under the administration of His Eminence Evlogii of Volyn’, until correct and uninhibited contact can be established between Petrograd and these dioceses and churches. His name is to be commemorated in the designated churches in lieu of the name of His Eminence the Metropolitan of Petrograd.”

Before the revolution, all the Russian Churches in Western Europe had been under the jurisdiction of the latter. It is clear from the following letter of New Hieromatyr Benjamin of Petrograd to Archbishop Evlogii just how realistic it was to govern these churches from Soviet Russia:

“June 8/21, 1921, Petrograd. Your Eminence, most reverend Vladyko, I, for my part, give my full consent for you to govern the churches outside of Russia at this time when there is no contact with them – all the more so given that your temporary governance of the aforementioned churches has been recognized and ratified by His Holiness the Patriarch.

My soul ails for these churches, but it has not been possible to help them. The humble servant of Your Eminence, Benjamin, Metropolitan of Petrograd.”[2]Tserkovnyj vestnik [Church Bulletin], Paris, April-May 1954.

The only real disciplinary measure undertaken by His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and the executive bodies of the Holy Synod and Supreme Church Council under him was the decree of May 5, 1922 shutting down the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Church Abroad. This resolution is out of conformity with the Patriarch’s other actions from this period, such as: his thanks to Patriarch Dimitije of Serbia on March 16, 1922; his communiqué to Archpriest Theodore Pashovsky from May 23 of the same year, to the effect that he was only able to recommend Metropolitan Platon to be appointed to the North American see, but that he could not make this appointment “over the head” of the Supreme Church Governance of the Church Abroad. Recently declassified documents from the KGB archives show that the Bolshevik enemies of God sought to have the clergy of the free portion of the Russian Church condemned. To illustrate this claim, we could cite the following testimony: on May 3, 1922 – that is, two days before the Supreme Ecclesiastical Authority of the Church Abroad was dissolved – there was a secret meeting of the Presidium of the GPU to plan a trial for Patriarch Tikhon. The presidium, consisting of Yagoda, Samsonov, and Krasikov, resolved: “…To summon TIKHON to the GPU in order to present him with an ultimatum demanding his resignation, defrocking, and the anathematization of the foreign representatives of the active monarchist and interventionist clergy.”[3]Politbiuro i Tserkov’ [The Politburo and the Church]; M. Vostryshev, Patriarkh Tikhon [Patriarch Tikhon], Moscow 1995. “A fair analysis taking into account the historical context and the terminology in use in the church at the time immediately reveals the contradictory nature of Decree No. 347, which was deliberately implanted in it in order to signal that the Patriarchal administration in Moscow was under pressure from forces hostile to the Church, as well as a clear-cut effort to protect church life both within Russia and abroad from intervention by anti-ecclesiastical forces.”[4]Vestnik Germanskoi Eparkhii RPTsZ [Bulletin of the ROCOR German Diocese], No. 1, 1998. Its contradictory nature stems from the fact that Decree No. 347 concerns only the churches in Western Europe, without saying anything about dioceses in other parts of the world. In order to understand the atmosphere in which the decree was issued, we must pay attention that within a matter of days after his release, Patriarch Tikhon was put on trial. He spent nearly a year under arrest, while his deputy, Metropolitan Agathangel, reorganized the Russian Church along the lines laid out in Decree No. 362. In these circumstances, there was quite simply no one to whom the Russian diaspora bishops could report on how they had carried out the Patriarch’s decree dissolving the Supreme Church Governance of the Church Abroad.

∗∗∗

By force of the 1918 Decree on the Separation of Church and State, the Russian Orthodox Church was stripped of its legal status. The regime refused to bestow these rights upon the Tikhonite Church, but without them the activities of the Church gave the regime a potential opportunity to convict any ecclesiastic for violating the legislation on cults. Obtaining this legal status was made directly contingent on whether the Church complied with the demands of the God-hating regime. In the USSR, the first group to obtain full legal rights were the Renovationists. The Tikhonite Church, in its “holy deprivation of rights”, was restricted in its actions in its homeland, not to mention the impossibility of its carrying out any activities abroad. In such conditions, the existence of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, “which consists of those dioceses, dioceses, missions, and churches situated outside of Russia, and is an inseparable part of the Russian Orthodox Church”,[5]Temporary Directive on the ROCA, ratified by the Council of Bishops on September 9/22 and 11/21, 1936 was fully justifiable.

In its relations with the Soviet regime, the part of the Russian Church outside of Russia was guided by the decisions of the All-Russian Local Council of 1917-18. The Council recommended that all its children defend the freedom of the Church from subjugation by outside forces. His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon, and the bishops both in their Russian homeland and in the diaspora who were loyal to him, tried to preserve this inner freedom at all costs. It must be understood that there are different demands of those who are free and those who are bound by the enemies of the Church.

In December 1925, Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhny Novgorod assumed the reigns of governance of the Russian Church. In his so-called Draft Declaration of June 10, 1926 on the Church’s Relationship with the Soviet Government, Metropolitan Sergius wrote: “Here we must explain our stance on the Russian clergy who have left the country and formed a sort of ‘branch’ of the Russian `Church outside of Russia. As they do not acknowledge themselves to be citizens of the Soviet Union and do not consider themselves beholden to the Soviet authorities under any circumstances, the foreign clergy at times permit themselves to make hostile statements against the [Soviet] Union, and the burden of responsibility for these statements falls on the entire Russian church, whose clerics and hierarchs they remain, as well as on those clergy who reside within the borders of the [Soviet] Union and count themselves amongst its citizenry, with all the ensuing consequences. It would be an incommensurate response to crack down on the foreign clergy for their disloyalty to the Soviet Union with any kind of ecclesiastical penalties, and this would give further cause for people to say that we are being compelled to do so by the Soviet regime.” Further, Metropolitan Sergius writes about the necessity of distancing oneself from the “politicking clergy” abroad. The notion that it was impossible for the Moscow church authorities to administer the parishes outside of Russia was voiced by Metropolitan Sergius in a private letter to Archbishops Feofan and Seraphim, members of the Synod of Bishops of the ROCOR, on August 30, 1926, essentially suggesting that the hierarchs ought to structure church life along the lines of Patriarch Tikhon’s Decree No. 362. In December 1926, Metropolitan Sergius was arrested, but in March 1927, he was unexpectedly released. This time marked the beginning of a new period in his church policy. In Decree No. 95 of July 1/14, 1927, he proposed that Metropolitan Evlogii and all the Russian clergy abroad should give a written pledge of their loyalty to the Soviet government saying that they “will not allow as part of their public and especially ecclesiastical activities anything that could be taken as an expression of their disloyalty to the Soviet government”. Those who refused to follow this proposal or who did not reply before September 15, 1927, as well as those who violated the pledge, were to be removed from their positions and excluded from the Moscow Patriarchate. In the Declaration of July 1927 itself, he demanded “complete loyalty” of the clergy outside of Russia “to the Soviet government, in the totality of their public activity.” The punishment he set for those who refused to give the pledge recognizing the Soviet regime was, again, exclusion from the clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate (thereby indicating it was impossible to submit to it outside the USSR).

The clergy of the Russian Church Abroad could not make this pledge, owing to the fact that it never acknowledged the Soviet regime as legitimate, as well as for the following reasons:

1) As early as 1924, the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad with its 14 members had issued a verdict resolving not to carry out orders of the All-Russian Supreme Church Council that bore traces of compulsion by the Soviet Authorities, which could bring harm to the Russian Church Abroad.

2) The Russian Church Abroad was a church of refugees. The former legal consultant of the Holy Synod of the Polish Orthodox Church, K. N. Nikolaev, wrote in his work Pravovoe polozhenie Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi Naroda Russkogo, v rasseianii sushchego (Novi Sad, 1934) [The Legal Situation of the Orthodox Church of the Russian People in the Diaspora] : “The jurisdiction of the Russian Church Abroad does not extend to persons with Soviet citizenship, nor to church institutions serving the need of these same persons.” In turn, Soviet citizens in other countries were forbidden to take up contact with Russian émigrés. In accordance with their status as refugees, the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad held Nansen passports and were under the protection of the country in which they resided. The recognition of the government of the USSR in the declaration of loyalty would in effect have entailed the termination of their status as refugees, and would have led to them either accepting Soviet citizenship or coming into conflict with the government of their own country. For example, as of 1927, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, did not recognize the USSR diplomatically. In his decree of June 20, 1928, Metropolitan Sergius declared in general terms that any clergyman who recognized his Synod without taking up Soviet citizenship was to be relieved of his clerical duties.

3) According to the All-Russian Local Council of 1917-18, the rights of the Patriarchal locum tenens himself can be reduced merely to leading the church up to the next Local Council. Of course, this resolution does not take into consideration the situation of the Church under persecution. Metropolitan Sergius was merely the deputy of the Patriarchal locum tenens, Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsa. After being released from prison in 1927, Vladyka Peter did not approve Metropolitan Sergius’ church policy – nor did dozens of other bishops of the Russian Church within Russia. They thought that Metropolitan Sergius’ actions far exceeded his powers and were a form of usurpation of authority in the Church, and a violation of the principle of conciliarity and of Patriarch Tikhon’s testament concerning the preservation of the inner freedom of the Church. In the situation at hand, complying with Metropolitan Sergius’ demands would, for the Russian Church outside of Russia, have meant partaking in his usurpatory actions.

This was the atmosphere in which, on June 22, 1934, Metropolitan Sergius and his Synod issued Resolution No. 50 suspending the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. Just before then, in those same years, Metropolitan Sergius and his Synod had imposed suspensions on all the bishops in Russia who did not wish to follow his church policy. A testament to how abnormal this situation was, was the fact that in 1934, Metropolitan Sergius suspended five metropolitans both in their homeland and in the diaspora. This was an unprecedented phenomenon in the history of the Russian Church. Metropolitan Sergius’ harsh policy concerning the requirement for the Russian Clergy abroad to be loyal to the Soviet Union stirred up a protest among bishops of the Russian Church within Russia itself.

∗∗∗

Thus, in the mid-1930s, the following Church entities existed outside of Russia:

1) the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. In 1935, the previously independent bishops of North America submitted to the Synod administratively;

2) Metropolitan Evlogii, who had broken away from the Synod and recognized Metropolitan Sergius’ authority over him, but subsequently, in 1930, gone over into the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople;

3) those who did not desire to leave the Moscow Patriarchate with Metropolitan Evlogii and remained under Metropolitan Sergius’ leadership, and who formed parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate in Western Europe (such parishes appeared in North America in a similar manner).

In the situation at hand, handing over pre-Revolutionary church property to Metropolitan Evlogii would have entailed its loss for the autocephalous Russian Church. Metropolitans Elevfevriy of Lithuania and Vilnius, Bishop Benjamin of Sevastopol, and Archbishop Sergius of Tokyo and Japan were under Metropolitan Sergius’ leadership. The first looked after the parishioners of the Moscow Patriarchate in Western Europe, the second for those in North America, and the third for those in Japan. These three bishops were incapable of caring for the entire Russian church diaspora. The majority of their flock was in Lithuania and Japan, and the bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate had almost no parishioners in Western Europe and North America. Thus, it becomes obvious why there was a need for a unifying center in the sense intended by Decree No. 362 of 1920, which said that bishops who find themselves in similar circumstances ought to organize supreme instances of church governance themselves.

∗∗∗

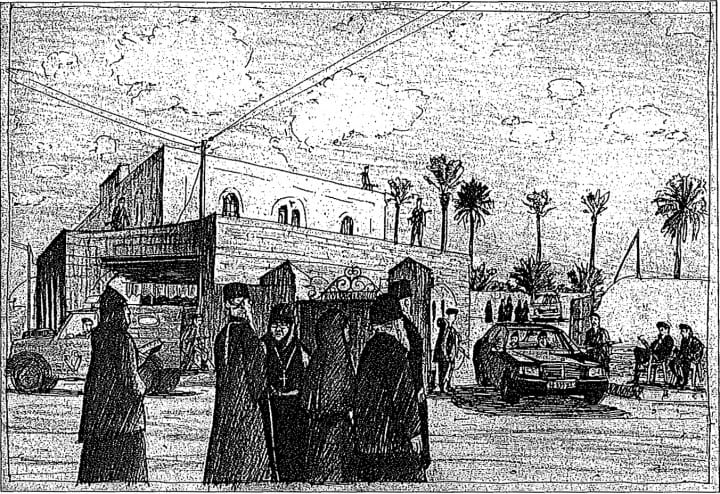

Another important factor is that, in the period under consideration, the governments of the various foreign countries, and not without reason, deemed the Moscow Patriarchate to be a “Soviet Church” and, accordingly, did not want it to have representations in their territories. For example, Palestine – a fact that is especially relevant now – was governed by Great Britain after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. In 1927, the United Kingdom was compelled to break off diplomatic ties with the USSR, which had been plotting an English revolution. Under such conditions, the absence of representatives of the Russian Church in Palestine could have led to the loss of her property. It was up to the ROCOR clergy to defend church property in the Holy Land against incursions by the British authorities. It had control over all the Russian Church property in Palestine up until the end of the British mandate. As it happens, in 1934, the British Government transferred a 10,000-square-meter piece of land on the right bank of the Jordan, next to the site of the Lord’s baptism, to the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission (REM). Thus, our Church, according to the Gospel parable, did not merely bury what it had received in the ground, but received interest on the talent entrusted to it.

Up until 1943 – the time when Stalin ordered the Moscow Patriarchate to be re-established – its clerics, as members of an organization without legal status, did not have the right to travel abroad to provide spiritual care for their flock. But even when they started to come to the West, the civil authorities always regarded their visits with caution.

Let us return to the matter of Palestine. After World War II, two states were established in this territory: Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The majority of the REM’s holdings were in the latter country. In 1954, the Jordanian authorities compiled a list of 125 names, including those of clerics of the Moscow Patriarchate, for whom entry into Jerusalem was forbidden. In 1958, monks from the Moscow Patriarchate were not allowed into Jordan.

Naturally, only the ROCOR – the church of the Russian diaspora – could provide new workers for the Russian ecclesiastical institutions abroad, as was required in order to sustain life in them. For example, Igumenia Pavla of the Holy Ascension Monastery on the Mount of Olives was appointed by His Beatitude Metropolitan Antony from Khopovo Monastery in Serbia.

Of course, the Russian refugees were every bit as much flesh-and-blood people as those who had remained behind in the homeland. Mistakes were made. They were not able to preserve all the pre-Revolutionary property of the Russian Church. For example, St. Andrew’s Skete on Mount Athos was lost. But the main thing is that the children of the Russian Church Abroad tried to do everything within their power to guard the heritage of the Russian Church that had been entrusted to them.

∗∗∗

After 1917, financial support from Russia ceased. The Soviet Union refused to be recognized as the legal successor-state to the Russian Empire. There were such indicative gestures as the destruction of the chapel at the Russian Embassy on Unter den Linden in Berlin in the 1920s. The burden of finding the means to maintain the property of the Russian church fell on the shoulders of the Russian refugees and exiles, who rightly saw it as their duty to preserve the holy places of the Russian people untouched by the profane hand of the Bolsheviks. In order to get a sense of the sums involved, it is sufficient to state that over 300,000 dollars went on repairing just one wall around the monastery in Hebron. And this is despite the fact that the Russian Church Abroad does not have the support of such financial powers as, for example, the Russian government.

In 1935, the Soviet regime relinquished control of all the pre-Revolutionary Russian churches in Germany. The note sent to Berlin reads: “The government of the USSR has no interest in the fate of the designated property and shall not react to any future inquiries on this matter.” In 1936, the German government gave the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad the status of a Public-Law Body (Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts). Thus, due to how the situation developed historically in this country, the other jurisdictions were unable to care for the property of the Russian Church. The Moscow Patriarchate was, again, regarded by the German authorities as a “Red Church”.

The ROCA’s Defense of Russian Church Property from the Incursions of Secular Authorities. Foreign Activity of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Palestine Society

Despite Metropolitan Sergius’ declaration and the subjection of the organization of the church to the Soviet government, not only did the Moscow Patriarchate not receive legal status, but it ended up facing total destruction. In 1935, Metropolitan Sergius was even forced to dissolve his Synod due to the fact that all its members had been arrested.

A change in state religious policy in the USSR occurred in 1939. In order to spread Soviet influence amid the Orthodox inhabitants of the territories of the Baltic, Western Ukraine, Bessarabia, and Belarus’ that had been occupied in 1939-40, the regime called upon the Moscow Patriarchate. It was from this time onward that the Moscow Patriarchate’s outward political activities began to take shape; to this day, these remain connected with its “cold war” waged against the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. In examining these activities, we shall only discuss the fate of the parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia in the free world, not those in Eastern Europe. In 1945, in the parish of the Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Berlin, which was located in the French Zone of Occupation, an assembly was organized that decided to transfer the church to the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate; it consisted of Soviet service members who had been brought in on trucks specially for this purpose. The church, which had been built by the German government and given as a gift specifically to the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, had never belonged to the Moscow Patriarchate. The Cathedral of Saint Nicholas of the Russian Church Abroad in Vienna was likewise seized. When the Brotherhood of Saint Job of Pochaev petitioned to have at least some of their books seized by Soviet Army returned, they were met with the following resolution by Patriarch Alexis I: “Since the Brotherhood of Saint Job of Pochaev is in a hostile position vis-à-vis the Soviet regime, the wagonload of books seized by the Soviet armed forces is considered to be a spoil of war.”[6]Archbishop Vitaly Maximenko. Motivy moei zhizni [The Motives of My Life]. Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1955. After the war there came a bounteous outpouring of Soviet funds from the Moscow Patriarchate to the Eastern Patriarchates, with the Moscow Patriarchate positioning itself as the Church of All Russia, while at the same time attempting to achieve Soviet foreign policy goals, as testified by recently published documents from Soviet archives.

Some clergymen of the Moscow Patriarchate who were sent abroad were also members of the Soviet foreign intelligence services. For example, it recently came to light that Priests T. Borshch and V. Petliuchenko studied parish registers in Canada in order to craft believable cover stories for Soviet intelligence agents.[7]Bronskill, Jim, “KGB Clerics Spied in Alberta”, in: Calgary Herald, October 6, 1999. In Israel, after the USSR broke off diplomatic relations with the country in 1967, Soviet spies operated under cover of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission of the Moscow Patriarchate. This is confirmed by the account of Khagon Antarasian, who was born and raised in Jerusalem, and who was made to report to the Moscow Patriarchate’s mission on the state of the Armenian community in Jerusalem.[8] As noted by V. Nefesh from Jerusalem in Slovo Tserkvi No. 3, 1973.

∗∗∗

Another important aspect of the ministry of the Russian Church Abroad was the defense of church property that had historically belonged to the Russian Church, from the incursions of secular authorities. Such intrusions generally came from the government of the USSR, although as discussed above, the British authorities also made attempts to seize Russian church property in Palestine.

Here one must take a moment to reflect on the significance of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society (IOPS) in the matter of pre-Revolutionary Russian Church property. Church property in Palestine never belonged to the Russian state, but was registered under the ownership of the IOPS or other persons, for example, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, the first president of the IOPS. Alongside the IOPS, the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission managed the church’s real estate in Palestine. After the Bolsheviks came to power, they confiscated “all the Society’s assets in Russian banks and the four-story building in Saint Petersburg that housed the Society’s headquarters and library. Many members of the IOPS perished in captivity or left the country with the White Army.” [9]Peresypkin, Oleg. “Pravoslavnoe Palestinskoe obshchestvo vnov’ stanovitsia imperatorskim” [“Orthodox Palestine Society is Imperial Again”], in: Nezavisimaia Gazeta, April 4, 1993. These exiled members of the IOPS continued the Society’s work from abroad. After the 1917 revolution, the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in the Holy Land submitted to the Synod of Bishops of the Russian Church that looked after her flock outside of Russia.

In Soviet Russia in 1918, the Russian Palestine Society (RPS) was established as an academic organization, and, just like the Moscow Patriarchate, it was used abroad to accomplish tasks set by the government of the USSR regarding the property of the Russian Church.

In 1948, the Israeli authorities seized property of the Russian Church Abroad in the part of Jerusalem occupied by them; they did not turn it over it to the RPS, but rather to the government of the USSR, which, in turn, handed over a portion of the property to the Moscow Patriarchate and sold the rest to Israel. However, it is clear from the following fact that the Bolshevik regime had control of the property of the Moscow Patriarchate. In early 1960, the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission (Moscow Patriarchate) gave the Communist Party of Israel the gift of a parcel of land opposite the well where the Virgin Mary used to go to draw water in her youth. The Israeli communists – evidently inspired by the example of their comrades in the USSR – at first proposed building a movie theater and later a parking lot on this piece of land.[10]Maariv, May 14, 1969, For some reason, in the emotionally charged statements we now hear against the Church Abroad, no one seems to recall this piece of land, which had been acquired through the donations of citizens of the Russian Empire who would hardly have consented to such a decision.

In the 1990s, the name of the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society was restored to the Russian Palestine Society; this new organization considers itself to be the sole legal successor to the pre-Revolutionary IOPS. It is clear, though, that just as in the past, it is an instrument of the government, only now of the Russian government rather than that of the Soviet Union. For example, on a piece of land in Jericho with a citrus garden previously belonging to the IPS, which it seized in 1995, an inscription was put up: “Property of the Russian Federation”. In September 1997, staff at the Russian Consul in Gaza declared that the Lavra of Saint Chariton, which belonged to the ROCOR and is situated near the autonomous Palestinian territories, is also the property of the Russian Federation.

The IOPS’s guesthouse and the parcel of land attached to it, which were seized this year in Jericho, are also considered to be the property of the Russian Federation; it is suggested that it is to be used for consular purposes. At present, there is nothing to suggest that representatives of the Palestine Society from Russia are present there.

∗∗∗

It is my hope that the above account of events concerning the relations between the Moscow Patriarchate, the Russian Palestine Society, and the Soviet and Russian states make it more understandable why the ROCOR has defended the property of the Russian Church from outside incursions. A vivid illustration of the differing relation of ROCOR and Moscow Patriarch bishops to pre-Revolutionary Russian property is provided by a story from the life of the Russian Orthodox Church mission in Peking. In 1924, its head, Metropolitan Innokentii (ROCOR) was able to defend the mission’s property from incursions by the government of the USSR by demonstrating to the Chinese authorities that the atheistic Soviet state could not be a legal successor to the Church. 20 years later, the mission was a part of the Moscow Patriarchate and its head was compelled to prove the opposite. The result was that a Soviet embassy was built on the grounds of the mission and the church – one of the great holy sites of Orthodox China, built on the blood of the first Chinese martyrs – was destroyed by order of the Soviet ambassador.[11]Priest Dionisiy Pozdniaev, Pravoslavie v Kitae [Orthodoxy in China], Moscow, 1998.

Thanks to what has been said above, it is clear that the ROCOR is not some kind of alien, foreign organization, as it is perceived in Russia, but rather the Russian Orthodox Church exiled from her homeland. The ROCOR’s location outside its homeland is due to the same historical factors that led the Moscow Patriarchate to come under the authority of the Bolsheviks. Therefore, it is only natural for the Russian Church Abroad to have care of the property of the Russian Church. For is the property of Russian Church, and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia is “flesh of its flesh”. Historically, it is evident that during the years of communism, no one else could take care of this property to the same extent that the ROCOR did in preserving it for the Russian Orthodox people, for whom the holy places under the control of the ROCOR are always open. At the present time, it seems fully justified to address the government of the Russian Federation and inform it of the truth about the Russian Church Abroad. Maybe then, “with God as our witness”, a change might take places in the hearts of our present persecutors. In the event that such an apologia were to be rejected or not to bear any fruit, we would be able to say that we had taken all possible steps to preserve the property of the pre-Revolutionary Russian Church.

References

| ↵1 | E. I. Makharoblidze, “20-letie rossiiskoi tserkovnoi “konstitutsii”” [“The 20th Anniversary of the ‘Constitution’ of the Russian Church”], in: Pravoslavnoe obozrenie [The Orthodox Review], No. 11-12, 1940. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Tserkovnyj vestnik [Church Bulletin], Paris, April-May 1954. |

| ↵3 | Politbiuro i Tserkov’ [The Politburo and the Church]; M. Vostryshev, Patriarkh Tikhon [Patriarch Tikhon], Moscow 1995. |

| ↵4 | Vestnik Germanskoi Eparkhii RPTsZ [Bulletin of the ROCOR German Diocese], No. 1, 1998. |

| ↵5 | Temporary Directive on the ROCA, ratified by the Council of Bishops on September 9/22 and 11/21, 1936 |

| ↵6 | Archbishop Vitaly Maximenko. Motivy moei zhizni [The Motives of My Life]. Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1955. |

| ↵7 | Bronskill, Jim, “KGB Clerics Spied in Alberta”, in: Calgary Herald, October 6, 1999. |

| ↵8 | As noted by V. Nefesh from Jerusalem in Slovo Tserkvi No. 3, 1973. |

| ↵9 | Peresypkin, Oleg. “Pravoslavnoe Palestinskoe obshchestvo vnov’ stanovitsia imperatorskim” [“Orthodox Palestine Society is Imperial Again”], in: Nezavisimaia Gazeta, April 4, 1993. |

| ↵10 | Maariv, May 14, 1969, |

| ↵11 | Priest Dionisiy Pozdniaev, Pravoslavie v Kitae [Orthodoxy in China], Moscow, 1998. |