The Nuns of Khopovo Convent[1]These notes were taken down by me during discussions with my sister, Maria Kullmann (1902-1965). She had a special gift of establishing deep personal contacts with many and often unusual people. … Continue reading

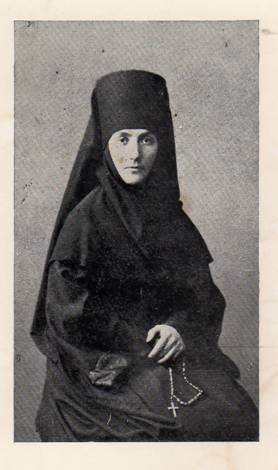

I was the first of the young Russians in Belgrade to discover Khopovo Convent. It was here that nuns of the convent of Lesna had found a temporary resting-place; they had left Kholmshchina during the war, and after many wanderings had eventually come to Serbia. At the head of the community were Reverend Mother Nina and Mother Katherine—the nun (invested with the schema) who had founded Lesna.

Late in the autumn of 1922 I set off alone for Frushka Mountain, seventy kilometres from Belgrade, where the convent stood. The train took me as far as Rooma station; a nine mile walk lay ahead. It was a frosty morning, the trees were white with hoarfrost, and I walked briskly towards my alluring goal. At first the road led straight along the flat Danube valley, but after the small town of Trig it began to wind uphill, and thick forest enveloped me on every side. Soon, through the bare branches, I saw the green cupolas of the baroque convent: until 1918 Frushka had been within the Austrian Empire.

As I walked along I prayed, not knowing how I should be received by the nuns, nor what my meeting with them might give me. The first person to notice me was Sister Domna; later she and I became close friends. She was so delighted to see me that I knew at once I was to be a welcome guest. She took me to a cell, and after I had rested I was presented to Reverend Mother Nina, who gave me her blessing to spend a few days at Khopovo.

Such was my introduction to that wonderful community. On that first, blessed visit I found deep understanding with Mother Katherine, with Father Alexei Nielyubov, the chaplain, and with many of the nuns; and I touched the wonder working ikon of the Mother of God of Lesna, which made the experience of those memorable days the more profound and the more radiant.

Reverend Mother Katherine (nee Countess Efimovskaya, 27.8.1850— 10.10.1925) was over seventy when I met her. She had long ago, in 1908, handed over the direction of the community to her successor, Mother Nina, but her mind and memory were as live as ever. She greeted me with extraordinary warmth, and I had a number of unforgettable talks with her. She readily shared her life’s experience with me, disclosing her most intimate thoughts. She was very happy that I was reading theology, because she had always believed in the importance of advanced theological studies for Russian women.

Mother Katherine’s father was Count Boris Efimovsky, her mother Princess Khilkova. Her parents were devoted to the church, whose ceremonies and traditions they lovingly observed. Her great interest from an early age was Russian literature, in which subject she graduated from Moscow University at the age of nineteen. Her short stories and novellen appeared in The Russian Messenger and other journals, attracting the notice of Turgenev, Markevich and other literary figures. Later she corresponded with Dostoievsky. She felt herself closest to the Slavophils, and was an intimate friend of the Kireevs and the Aksakovs. She was deeply influenced by S. A. Rachivsky, the founder of an Orthodox village school on his own estate of Tashev. But she could never be wholly satisfied either by literature or by a social life. She wanted to give herself totally to the service of the church, and the idea of the religious life began to attract her more and more. Nobody supported her in her wish, however; her family and friends all considered it a burst of youthful enthusiasm, unrelated to the heavy burden of the monastic life. The clergy did not believe that she was serious in her intention, and one prelate observed that, ‘No good can come out of a change from a ball dress to a nun’s habit’. Even her Slavophil friends tried to dissuade her, on the grounds that she could do more for the church and for education if she remained a laywoman. But she felt her vocation ever more strongly, and decided to seek the opinion of the famous elder, Father Amvrosi (Grenkov, 1812-91). Father Amvrosi was bedridden with illness, and used to receive his visitors lying down. When he saw the unknown girl, however, he rose from his bed, put his monk’s cloak on her, and said, ‘A great road lies ahead of you, you will be an abbess’. These prophetic words decided the young countess’s future. In 1885 she was given the task of building up the community of the Holy Mother of God at Lesna. At first there were only five other sisters and two orphan girls. In 1889 she took her final vows and the community became a convent. Just before the war in 1914 there were 400 nuns in Lesna, 100 staff, and 700 children. The foundation had six churches, apart from the schools, hospitals and other buildings. As many as thirty thousand pilgrims would come at the feast of the Blessed Trinity and at the monastic feasts, and some forty priests would arrive to confess the crowds of the faithful and to administer Holy Communion.

Reverend Mother Katherine told me she had entered the religious life not in order to forget the world but to transform it. The foundress of active religious life for women, she believed that the time would come when Russian women would have to take upon themselves the defence of the

She worked both in word and deed to re-establish the ancient order of deaconesses, and her efforts were almost successful: had it not been for the War and the Revolution deaconesses would have been introduced into the Russian Church.

Deeply interested in theology, she brought many well-educated girls to Lesna, and was convinced that for many Russian women the study of theology could be a way to the knowledge of God. She would wrestle with questions arising from points of dogma, seeking a solution and never content with a trite explanation. For instance she could not accept the possibility of eternal torment: this was incompatible with the God of love and mercy. Dostoievsky’s idea of the redemptive power of beauty was very dear to her. Her own ascetic way did not kill her interest in literature; one of her favourite stories was Kuprin’s ‘Sulamif.

She spoke to me a lot about all she had seen of Russian peasant women. ‘Russian women’, she said, ‘long for feats of endurance. They will remain in prayer for nights on end, and are undismayed by the most rigorous of fasts. But the hardest thing for them is obedience; western nuns give up their own will, but Russian nuns are rarely capable of this. Their attachment to the world is linked with the mother in them. When I started to take in orphan girls to bring them up in the community, I was met with resolute resistance. Many of them told me later that the greatest sacrifice their vows had meant for them was that of not having children; “now we have to look after other orphans, and our care for them take us back into the world”.’

For Mother Katherine herself the works of love were the most important of all religious feasts, and she boldly rated them higher than any ascetic practices.

Apart from the inspiring talks I had with the wise Mother Superior, I had many conversations with the nuns. I was very anxious to know what had brought each of them to the religious life. Most of them were quite ready to answer my questions. My greatest friend among them was the novice Domna, who had first greeted me on my way into the convent. She was already elderly, but like most of the nuns of Lesna was still a novice: few of them took their final vows before the end of their lives. Domna told me that when she was twelve years old she dreamed that she saw an enormous cross spread over the whole sky, and she heard our Lord’s voice saying, ‘You are crucifying me again with your sins’. After that dream she longed to become a pilgrim. At first her parents would not let her go, but when they saw how resolute she was they gave their consent for her to go to a nunnery. She left home in search of a community that suited her, found Lesna and stayed there for ever.

Of all my friends among the Khopovo nuns, Mother Milentina occupies a special place. She was one of the first to join the community at Lesna, and Reverend Mother Katherine was therefore particularly attached to her. She was of the merchant class and had had a certain amount of education. She was very old when I met her, and her little, wrinkled face looked like a baked apple. Among the lines of her face her blue eyes stood out like a pair of bright buttons. She often used to screw up her eyes when she talked to me, and then tears would run from them. She possessed the gift of second sight, which she hid under a mask of yurodstvo (of being ‘a fool for Christ’s sake’). During church services she often used to go up to one of the people praying and murmur a few rapid, broken phrases into their ear. What she said always corresponded exactly to the secret petition of the person praying. I once experienced her second sight myself. I had arrived at Khopovo very upset about something that had happened to me on the way there. When I was catching the train in Belgrade someone had stolen my purse. It had contained not only all my money and my ticket, but also—and this was what really worried me—the key of our friends’ house, and an important letter from my father to a certain doctor in Belgrade, which I had promised to deliver as soon as I returned. Despite this loss I had decided to continue my journey. The ticket clerk believed me, and gave me a new ticket which I said I would pay for on my return. As soon as I reached

Khopovo I went to the church and found a service in progress. I was distracted in my prayers by doubt as to whether I should ask God’s help, or whether I had no business to pray about something which was, after all, so ‘trivial’. As this word passed through my mind Mother Milentina came quickly up to me and whispered into my ear, ‘With God nothing is trivial’. To my amazement she had read my thoughts and settled my doubt.

My adventure ended in the most unexpected way. When I returned to Belgrade I went to the doctor to explain how I had lost my father’s letter to him. Seeing me in the waiting room he called me straight into his study and asked me if I could throw any light on an inexplicable letter he had just received. It turned out to be from my ‘good’ thief, thanking the doctor for the money and returning the purse complete with ticket, key and letter. I am sure it was Mother Milentina’s prayers which brought them back to me.

On another occasion, I remember, Mother Milentina came up to me and to other members of the congregation and said, ‘Pray for Fedor Mikhailo-vich Dostoievsky, pray for the repose of his soul. He foresaw it all, he wrote about it all. There’s one book, God forbid that the name of it should be uttered in church.’ (She referred to Dostoievsky’s novel called The Devils.)

During the lifetime of Mother Katherine, Mother Milentina was for many years a sacristan, fulfilling her duties with the greatest zeal. She was always the first to come into the church, and always kept everything in perfect order. After Mother Katherine’s death Mother Nina appointed her to a new task — that of tending the geese. Mother Milentina accepted this decision as a punishment for the sin of pride. She asked permission to move into the cellar, and chose for herself a dark, windowless cell. She looked on the degradation as a way towards intensifying her life of prayer. The geese became her friends and her instructors. She would let them out before sunrise, and spend the whole day with them, talking to them as to rational beings of God’s creation, greeting them in the morning, and asking their forgiveness and making the sign of the cross over them as she bade them good-night. ‘The geese obey me”, she would say, ‘they reveal to me the secrets of creation. And we are guilty before all of them.’

Mother Milentina was always particularly good to me. She gave me a little ikon of hers, and when I was married she sent me a gift of a little glass and several goose feathers. She explained in a letter that the glass was the cup of fullness, and that the feathers were to sweep all the evil out of the house. Mother Milentina died before Father Aleksei, presumably in

During my conversations with the nuns of Khopovo I often heard mentioned the name of the pilgrim Lydia. She had left Khopovo shortly before my arrival, after living there for about a. year. She had evidently made a profound impression on every one in the community; many considered her a saint, and were amazed by her podvigi (her ascetic feats). They told of how summer and winter she went about barefoot in a light cotton dress, with a white kerchief round her head. She fed on water and herbs. In winter the church at Khopovo was bitterly cold ; even the nuns, used as they were to an austere way of life, had to wear felt boots, and wrap themselves up in warm shawls over their winter habits, and despite this they could hardly bear the cold inside the church. The pilgrim Lydia would remain throughout the long services in nothing but her summer dress, standing on the stone floor with no stockings and only light slippers on her feet. She apparently did not feel the frost at all. The nuns told me too how she would spend long nights in prayer, usually going out into the forest around the convent. Several times the nuns saw her standing in prayer, and were frightened of the strange things that happened during these nightly vigils. They heard what sounded like the roaring of wild beasts, and sometimes an icy whirlwind swirled around her. Father Alexei Nielyubov, the chaplain of the community, a wise and much experienced man, who later became confessor to the many Russians from Belgrade who came to make a retreat at Khopovo, confirmed that these stories about Lydia were by no means exaggerated. He also told me that he had not felt himself capable of being her spiritual director, and had given his blessing to her wish to return to Russia to find the director she needed. Lydia decided to go on foot, through Romania, and therefore left Khopovo. The nuns did not know if she had succeeded in crossing the Soviet frontier. I found the stories about this unusual pilgrim intensely interesting, and little guessed as I listened to them that I should not only meet her, but even play a certain part in her strange fate.

In 1924, two years or so after my first visit to Khopovo, I saw a nun in the Russian church in Belgrade. I was struck by her face, which seemed to radiate light, and her blue eyes shone wonderfully, like crystals. When I saw her I thought, that is just the kind of face I would expect the pilgrim Lydia to have. With the boldness of the young I went up to her as we were coming out of church and asked her, ‘Who are you?’ She was not surprised by my question, and answered, ‘My name is Mother Diodora’. Hearing this unfamiliar name I said, ‘Oh, but I thought you were pilgrim Lydia’. This she evidently had not expected, and she answered quickly, ‘Yes, I was Lydia, but how do you know about me?’ After that we entered into a most lively conversation, there in front of the church. Mother Diodora told me that she had arrived that morning from Romania to see the Patriarch of Serbia to ask him for a convent for her nuns. She did not know where she might stay, and so I suggested she come to the ‘ark’—the hovel on the Senyak where I lived with my brothers and sister and a few close friends. Mother Diodora accepted with delight, as she had no money. She spent a few days with us, and every evening we would talk until well after midnight. She told me a great deal about her life. She was born in Kiev, in a doctor’s family. I think her name was Dokhturova. When she was about twelve she came up against the question of God, and began to pray that he would reveal himself to her. At first she prayed before she went to sleep, but gradually her night prayers began to take up more and more time. Then she decided to go out into the garden to pray, and soon she spent the whole night there. When she reached the point when she no longer felt either cold or fatigue, she decided to become a wandering pilgrim. Her parents could not stop her. To begin with she would return to Kiev every winter and continue her studies in the High School. Her favourite subject was Russian literature. It was characteristic of her that she considered Mayakovsky and the futurists more spiritual than Blok and the symbolists, because she felt that Mayakovsky had found a way to man in his nakedness, had touched his very spirit. There was still one obstacle to her overpowering wish to give herself totally to prayer, and that was her love of art. When she was seventeen or eighteen she went on foot to Italy. On the way she had an extraordinary encounter. When she reached the south of France she was stopped by a woman who came out of her cottage and said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you for a long time. God revealed to me that I was to receive you in my house.’ She was a Russian woman called Sera-fima Konopleva, who lived lived a hermit in the mountains above Cannes. Mother Diodora added, ‘We loved each other like our own souls. I spent a few days with her, talking of God and of prayer.’

Once she reached Italy Lydia went from town to town in order to ‘part with beauty’. And then she realised that art no longer had any hold over her, that the masterpieces of the Renaissance had become for her like toys for grown-ups, and could no longer keep her in the world. In the church in Bari, she prayed before the relics of S. Nicholas to be shown where she should go. An unknown man came up to her and said, ‘Go to Montenigro, a saint lives there who will be your instructor’. And so she did. In Montenigro she lived in a cave, her time spent in silence and in prayer. At first she fed only on grasses, then shepherds who had seen her there began bringing her maize bread every morning. She lived on there until she met some people who gave her spiritual help. When they had given her all they could, she found the saint of whom she had been told in Bari, and he advised her to go to Khopovo.

On her way from Khopovo, hoping to go through Romania and thus back to Russia, she stopped at a convent in Bessarabia. It was in this convent that Mother Diodora lived, a yurodivaya, unwashed, unkempt, her speech incoherent, and whom every one thought to be crazy and good for nothing. When Lydia was about to cross the frontier this pitiful, crazy creature came up to her and said, ‘I want to initiate you into my secret. God has revealed to me that I have not much longer to live. My craziness is a mask which I wear to cover my podvig of prayer for Russia and for the world.’ She talked of her innermost spiritual life, and for Lydia this was like a new dedication.

A few days after their conversation, Mother Diodora was found dying near the river. When she was carried into her cell, she was shining with light. The nuns’ eyes were opened, and they realised that they had despised and ill-treated a saint. She died after receiving the Blessed Sacrament, radiant in the grace of her total giving of herself to God.

A few days after their conversation, Mother Diodora was found dying near the river. When she was carried into her cell, she was shining with light. The nuns’ eyes were opened, and they realised that they had despised and ill-treated a saint. She died after receiving the Blessed Sacrament, radiant in the grace of her total giving of herself to God.

The priest, amazed at what had happened, invested the pilgrim Lydia, giving her the name of Diodora. This led to a division in the convent, as some of the nuns wanted the newly invested podvizhnitsa (ascetic) to be abbess. The new Mother Diodora did not want to prolong the schism. She decided to return to Serbia with some of the nuns, where she was promised a convent not far from Tsaribrod on the Bulgarian frontier. After the Second World War, when Tito’s government was expelling the Russians from Yugoslavia, Mother Diodora should have been sent to France. The French authorities were granting visas to clergy and religious. But Mother Diodora asked to be sent to Russia. When this turned out to be impossible she decided on Albania, and said, ‘A nun must not look for peace, but for suffering’. According to rumour she is still pursuing her ascetic way in Albania.

References

| ↵1 | These notes were taken down by me during discussions with my sister, Maria Kullmann (1902-1965). She had a special gift of establishing deep personal contacts with many and often unusual people. These reminiscences refer to her student years (1921-6) when she was enrolled as a student of theology at Belgrade University in Jugoslavia. In 1926, having completed her studies, my sister moved to Paris, where she was in charge of youth work until her marriage to Dr. G. G. Kullmann in 1929. These reminis-censes were first published in Russian in the Novy Zhurnal (New Journal), New York, No. 87, 1967. Mrs. Kitty Stilworthy, Maria Kullmann’s friend, translated them into English, August 23, 1967. Nicolas Zernov (Sobornost, 8, 1969). |

|---|