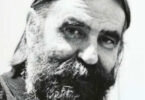

Here we commend to our readers a fragment from the memoirs of the Orthodox author Anatolii Krasnov-Levitin (d. 1991), titled Po volnam, po moriam [Across the Seas, Across the Waves] (Paris: “Poiski” Publishing House, 1986), which have become rare to find in book form and which are valuable for their frankness, as well as photographs from the archive of the Holy Trinity Monastery printshop. Archpriest Mikhail Protopopov, a historian of the Australian Diocese of the ROCOR, has published a quasi-hagiographical monograph (525 pp.) in Russian on Vladyka Paul, Archbishop Paul, 1927–1995. The memoirs of someone who knew the Archbishop so well and the extracts quoted from such rare documents as Archbishop Paul’s letter to the editor-in-chief of Radio Liberty (Radio Free Europe) demand attention.

During my first stay in Munich, I also came into contact with the church community there. The center of church life in Munich is a large building on the Salvatorplatz. The place has a curious history: in the very distant past, the 14th century, there was a queen of Bavaria who was Greek and, of course, Orthodox. A large number of Greeks came to Munich with her. There was a Greek cemetery here (it was not permitted to bury “schismatics” in Catholic cemeteries). A Greek Church of the Savior was built here, too. (Hence the name of the square: Salvator, or “Savior” in Latin.) This building, which rises up high above the town square, has been preserved until now almost without any modifications.

Next to it, in an ultramodern building that once housed a library, is the Russian Orthodox church.

We go in at 10 o’clock on a Sunday. This is where the liturgy is meant to take place. A large hall, open on all sides. No columns. An altar. Icons all around. Old-fashioned ones, based on ancient models. Yet it is immediately evident they were painted by local artists; the style is fairly primitive.

At 10 o’clock, people are beginning to gather. There are thousands of Russians living in Munich at the moment (at least 10,000–15,000)… a small Russian provincial town in this ancient Germany city. But only about four thousand of them attend church. The intelligentsia. Elderly ladies. Old men with a martial bearing. Young people: intense, modest boys and girls with good manners.

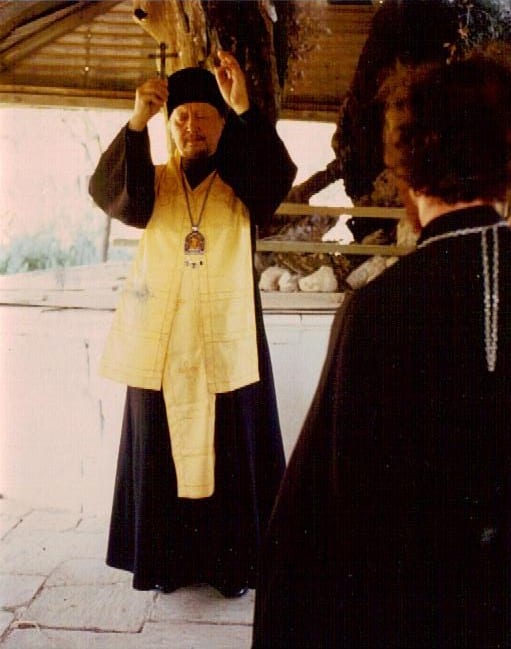

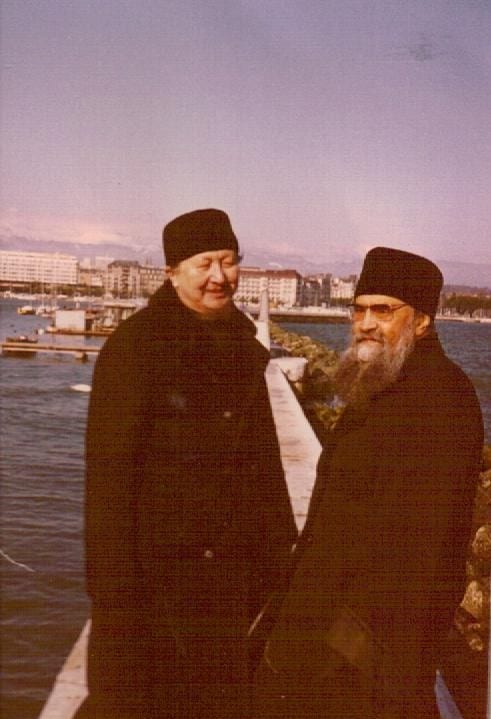

The Sunday liturgy is usually served by a bishop. In the 1970s, that bishop was Vladyka Paul (secular name: Mikhail Pavlov). I immediately came in contact with him. I got a phone call in my hotel room at one point. A male tenor voice: “This is the local bishop. Gleb Alexandrovich Rahr asked me to tell you that he will be in Munich the day after tomorrow.” Somewhat bewildered, I answered, “Thank you, Vladyko!”.

Subsequently, I saw Vladyka many times both during church services and in his home. He is a completely different kind of bishop than his senior brother in Geneva. From our first meeting he reminded me of the figure of a simple young monk which has been familiar to me since my childhood. I love such people: they are unceremonious, simple, talkative, cheerful, at times fervent… religious, but without any affectation.

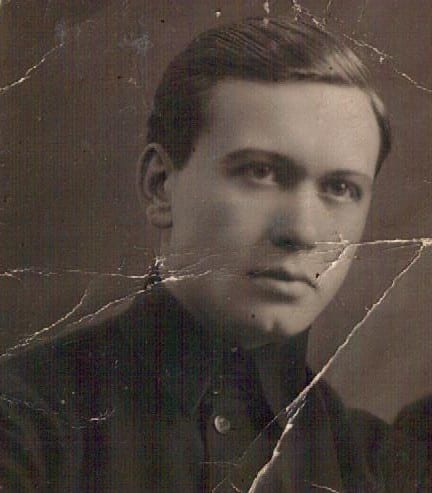

Bishop Paul (now Archbishop of Sydney, Australia and New Zealand, though at the time his title was Bishop of Stuttgart), whose secular name is Mikhail Pavlov, was born in Russia in 1927. He was caught up in the storm of the war with his mother—he evidently lost his father while a child— and made it to Poland, then to Germany. At the end of the war, he ended up in Paris.

I remember a colorful story he told me about how he ended up living in an attic together with another boy in Paris and they managed to procure a sack of champignons from somewhere. They lived off nothing but mushrooms for a whole week; they didn’t even have any bread. Champignons, as you know, are a very fine delicacy that is enjoyed by gourmands as a garnish in dishes. Whether or not they would have been appetizing to two boys weak with hunger in a Parisian attic is difficult to say.

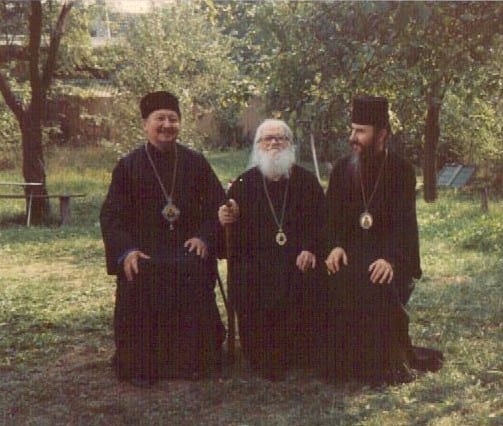

Later, Mikhail Pavlov and his mother ended up in Montreal, Canada, and it was here that they met Vladyka Vitaly, who showed an interest in them [In fact Fr. Pavel traveled with Fr. Vitaly since after the end of the war – ed]. Mikhail Pavlov was interested in the Humanities. In his office, you can see the collected works of the great Russian historian Sergei Solovʹov and a whole array of other famous historians. I recall how surprised I was when Vladyka unexpectedly recited an entire poem by one of the lesser-known but nonetheless talented Soviet poets. He completed a degree in languages and literature in Montreal. However, he had been attracted by the monastic life since childhood and he made his monastic profession at a very young age in 1947. His “Abba”, Vladyka Vitaly, was a strict ascetic—he had previously been the abbot of a monastery in Ciscarpathia—and under his leadership, Father Paul mastered the difficult art of asceticism. He celebrates the services well and evidently loves monastic services according to the Typicon. He is a good administrator who understands the life and the psychology of his flock, which to a large extent consists of people who have seen a lot in life, who were cast out of their native country, endured want and hostility, wandered all over, and know, to quote Dante, how “bitter is the taste of another man’s bread and … heavy the way up and down another man’s stair.” How could someone who as a boy survived off champignons in an attic in Paris not understand this?

And other Orthodox clergy in Munich. First and foremost, Fr. Sergei Matfeev. A zealous priest. Very spiritual, very attentive, very kind. And at the same time, interested in everything, with a broad formation. He brought his son to my first lecture. And he was patient enough to sit through the entirety of my long speech. Fr. Sergei died shortly thereafter. His wife also recently passed away; she was a wonderful, hospitable Russian woman.

I do not have any particular attachment to any nation, but then again, how could I, an outcast (half Jewish, half Russian, but really neither), a person with no definite nationality, have such an attachment in the first place? Yet I love Russian people, of the old type, now increasingly rare: open, straightforward, hospitable, and eager to help. Fr. Alexander Nelin made a similar impression on me. I went to him for confession twice. He made a good impression. They all have the traits of the priests I knew in my childhood and of Leskov’s character Fr. Savelii Tuberozov.

I believe that the photograph at the head of the article is not of Archbishop Paul but, rather, of his father. I am familiar with the photo and recall seeing it when my late father served as secretary of the A&NZ Diocese from 1980-1995.

Your comment makes a lot of sense. Thank you!