Bishop Mikhail was born in the Orlovsk-Sevsk Diocese in 1858. The Orlovsk-Sevsk Diocese (now called the Orlovsk-Livensk Diocese) is located SW of Moscow, and due E of Kiev, just inside the borders of Russia and outside the borders of Ukraine. In 1912, the year after Vladika Mikhail was consecrated to the Episcopate, his home Diocese contained 1046 parishes, 48 chapels, 15 Monasteries, 7 of which were women’s Monasteries, 843 Church Schools, 1 Diocesan Women’s School, 2 Spiritual Schools, 2 Theological Seminaries, 789 Parish Libraries, and 17 Almshouses. The Diocese published a periodical, the ‘Orlovskoe Eparkhialnii Vedomostii.’ The Diocesan Cathedral, located in the city of Orel, is named in honor of the Akhtirskaya Icon of the Mother of God.

Bishop Mikhail received an education that was similar to the education of most of the ‘learned monks’ of that time-attendance at Parish School, Spiritual School, Seminary, and, finally, a Theological Academy. Bishop Mikhail graduated from the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy in 1884, with a ‘Candidate of Divinity’ (equivalent to our Master’s Degree) Degree.

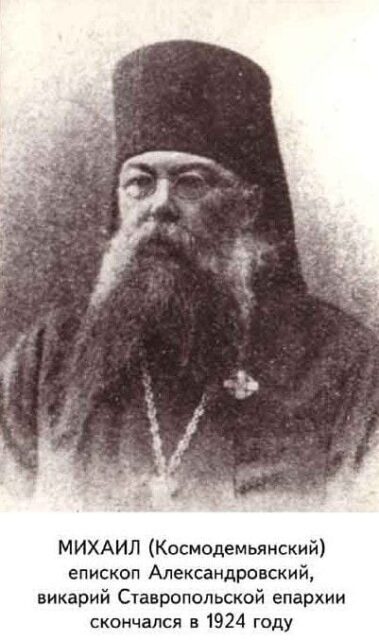

His service to the Holy Church was also similar to that of many of the ‘learned monks’ and future hierarchs of the day. This usually included some years of preparing young people to serve the Church. After finishing the Theological Academy, Bishop Mikhail taught for some time at the Spiritual Schools of the Orlovsk-Sevsk Diocese. In 1895, he was appointed as Inspector of the Diocesan Parish Schools, and the same year was ordained to the priesthood.

In 1901, then Father Mikhail was transferred to the Stavropolskaya-Ekaterinodarskaya Diocese, where he performed the same job he left in the Orlovsk Diocese-Inspector of Diocesan Parish Schools. The Stavropol Diocese (Stavropol is from the Greek, ‘Stauropolis,’ which means ‘City of the Cross’) is located in Southern Russia; the city itself is located midway between the Black and Caspian Seas in the Caucasus region, N of Georgia. From 1916 to 1922, the name of the Diocese was changed to Stavropol-Kazkavskaya. In 1904, Father Mikhail was appointed as Inspector of the Stavropol Spiritual Schools; in 1906 he was elevated to Protopriest and assigned to the Diocesan Consistory. In 1910, Protopriest Mikhail Kosmodamiansky was tonsured a monk, and elevated to Archimandrite.

On 12/25 May 1911, the Stavropol Diocese created its first Vicariate, Alexandrovsk. Archimandrite Mikhail was chosen to be the first Bishop of that Vicariate, and on 03/16 July 1911, he was consecrated to the Episcopate. The consecration took place in the Diocesan Cathedral of the Holy Apostle Saint Andrew the First-Called in Stavropol (‘Andreyevsky’ Cathedral).

The consecration was presided over by Archbishop (later Metropolitan) Agafodor (Pavel Flegontovich Preobrazhensky, 15 Dec 1837-1919) of Stavropolskaya and Ekaterinodarskaya. A few words are in order concerning Archbishop Agafodor, as he played a role in the future of his Vicar, Bishop Mikhail of Alexandrovsk. Vladika Agafodor suffered through a life of poverty and want during his youth. His father died when he was young, and he was raised by his mother, who was extremely poor. Despite their difficult material circumstances, Vladika Agafodor’s mother was able, with the help of God, to raise her son, from the beginning, in the Orthodox Faith, in obedience to the Will of God, the practice of self-control and a desire for the ascetic life. He was known as one who quickly went to those who were in need and assisted them to his ability. These lessons of his youth imparted by his pious mother left their mark on the future Metropolitan Agafodor, and guided his actions in his Hierarchical Service to the Holy Church. Vladika Agafodor was consecrated to the Episcopate in 1888, and assigned to the Stavropol Diocese in 1893. In Stavropol, Vladika Agafodor was known as hardworking and kind, indulgent, and zealous and firm in the field of missionary work and spiritual education. He was known as a spiritual writer, and among his works were ‘A Manual about the Law of God,’ ‘The Explanatory Prayer Book,’ ‘Lectures about Hope and Love,’ and ‘Lectures about Belief.’ In 1910 he was awarded the right to wear the diamond cross on his klobuk. He was known for his attention to spiritual education, and doubled the number of parish schools in the Diocese. He also greatly increased the number of churches in the Diocese, and paid special attention to missionary work, forming a special translation commission to make available the Holy Scriptures, Prayerbooks, Service Books, and other essential Orthodox literature in the languages of the Moslems and Buddhists who lived in the Diocese. Archbishop Agafodor served as a delegate to the All Russian Council of 1917-1918, representing his Diocese. He also helped to organize, and his Diocese hosted, the 1919 South East Russian Church Sobor. It is not known in what year he was elevated to Metropolitan. He reposed in 1919.

1917 was a year of catastrophic change in Russia. While it is the common folk who suffer most during such historical upheavals, the historical record is concerned primarily with the effects of such times upon governments, and sometimes, the Church. Awareness of the unparalleled importance of the Church in the life of Russia makes it easy to understand the great concern placed upon the the effects that this catastrophic change had on the Russian Orthodox Church. The All Russian Church Sobor, opening in 1917, brought sweeping changes to the Church, most notably the rejection of the uncanonical system of the government-controlled Holy Synod that administered the Church. It was, of course, replaced by the Patriarchate. The beginning of 1917 also saw the February Revolution, which forever changed the way in which Russia was governed. It is difficult to foretell how such changes that affect societies to their very core will be met by the people and institutions of those societies. The effect of the February Revolution on the Russian Orthodox Church was one that was, in large part, almost totally unbelievable. It is thought that perhaps one-third of the Hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church was in favor of the February Revolution. An almost shocking number of the Hierarchy not only approved of the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, but also did not favor the Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich as Heir to the Throne. This one-third wanted the autocracy done away with altogether. Perhaps not surprising is the fact that the clergy, the Diocesan Bishops and their Vicars reflected the opinions of the people of their respective Dioceses.

In the middle of Great Lent in 1917, Bishop Nikon (Bessonov, 1868-1919) of Yeniseisk & Krasnoyarsk sent a telegram ot the Chairman of the Provisional Government which read, ‘Christ is Risen! The change of government is good!’ Many Bishops freely stated opinions that Russia was ‘exhausted and fallen,’ and hoped for an ‘updating’ of Russia on the principles of ‘freedom, equality and brotherhood.’ Celebrating the ‘first solemn day of freedom in Russia,’ Archbishop Agafodor of Stavropol called down ‘the grace of God and God’s blessing’ on the works of the Provisional Government. In ‘the awe of the Truth of God,’ he pledged his ‘fidelity to build the new Russia.’ ‘Spontaneous’ holidays, known as ‘freedom holidays,’ took place all over Russia-in cities, towns, and villages. During these holidays, the Diocesan Bishops, followed by their Vicars and clergy, marched with Icons and banners, and were met with and joined by groups of the people carrying red banners and revolutionary slogans, singing revolutionary songs. On these occasions, the large gatherings (50-100,000) were taken advantage of to have the people present perform loyalty oaths to the new government. On one such occasion, Bishop Mikhail (Kosmodamiansky) greeted the garrison troops with an ‘URA!’ (‘hurrah!’) to the Provisional Government. In his homily for Pascha, Bishop Mikhail compared the autocracy to ‘satanic chains,’ by which all life of the citizens of Russia had been fettered. He went on to say that with the breaking of these chains, an all round ‘resurrection of state, political, public, national, religious and legal life of the country’ had begun. In another talk, Bishop Mikhail characterized Rodzianko, Kerensky and Miliukov as ‘foundations, pillars of a new, free, national -legal Russian life . . . ‘ It is not known how long the optimism of Bishop Mikhail, and his ruling Hierarch, Archbishop Agafodor, towards the new order in Russia lasted. Of course, by 1919, a very different situation prevailed. Gone were the ‘freedom holidays,’ as the Civil War was raging. Gone was the Provisional Government, Bishop Mikhail’s ‘pillars of a new, free Russia’ gone, exchanged for Lenin, Trotsky, and other ‘pillars’ of an entirely different sort. In the South, the Volunteer Army (White Army) was enjoying one of its periodic successes. General Denikin was in command.

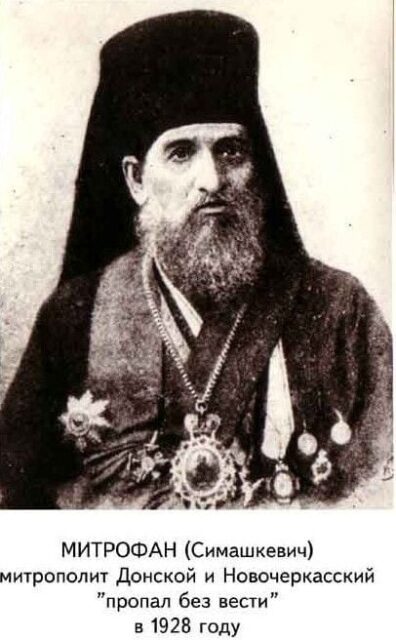

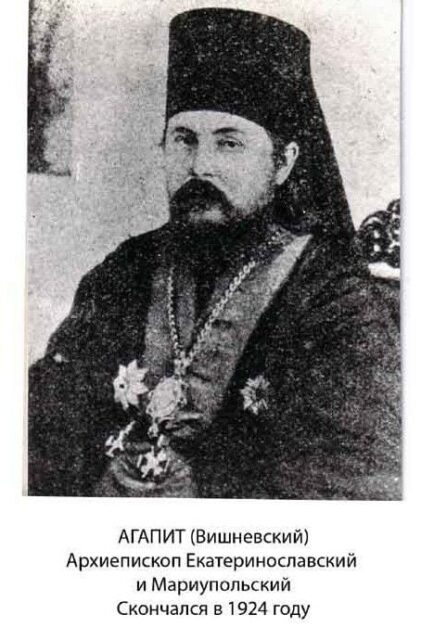

In early 1919, the Protopriest George Shavelsky, commanding officer of the Chaplains of the Volunteer Army, embarked on a procedure for the formation of a Higher Church Authority for the South of Russia. This was necessary because, due to the situation of the Civil War, there was no contact with Patriarch Tikhon in Moscow, a Church Authority was necessary to conduct the regular life of the Church in the area under the control of the Volunteer Army. General Denikin fully recognized the desperate predicament in the lack of any Higher Church Authority in the areas he commanded. Also, there was a clear and recent precedent for such a course, in Siberia, in the territory controlled by Admiral Kolchak. This was the Church Council in Omsk, presided over by Archbishop Silvester (Iustin Lvovich Olshevsky, 31 May 1860-Martyred 13/26 Feb.1920) At first, Archbishop Agafodor did not agree with holding the council without the Blessing of Patriarch Tikhon. Father George Shavelsky attempted to explain to Vladika Agafodor that the Council needed to be called exactly because they had no contact with Patriarch Tikhon, and Vladika Agafodor still would not agree. Father George then told Vladika Agafodor that Patriarch Tikhon would have nothing against that which was both good and necessary; although Vladika Agafodor still was not convinced, he finally relented and gave his consent. The South East Russian Church Sobor began on 19 May 1919 in Stavropol with a solemn Divine Liturgy and Moleben served by Archbishop Agafodor (Preobrazhensky) of Stavropol, whose Diocese hosted the Sobor; Archbishop Mitrophan (Simashkevich); Archbishop Dimitri (Prince David Ilych Abashidze, 12 Oct 1867-1942 or 1943); and Bishop Mikhail (Kosmodamiansky). The Chairman of the Sobor was Archbishop Agafodor, by virtue of his seniority as the oldest hierarch present by date of ordination. Other Hierarchs at the Sobor were: Archbishop Agapit (Anton Iosifovich Vishnevsky, 16 July 1867-1924); Archbishop Arseny (Alexander Ivanovich Smolenets, 1873-06/19 Dec 1937) of Semipalatinsk; Archbishop Dimitri (Prince David Ilych Abashidze; in schema, Antony) of Tauris and Simferopol; served as Vice President of the Higher Church Administration of South Russia, Bishop (later Archbishop) Gabriel (Chepur, Dec. 19, 1874-Mar 01/14 1933) of Chelyabinsk and Troitsa, later emigrated to Yugoslavia with Met. Antony (Khrapovitsky) and ordained St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco to the priesthood; Bishop Germogen (Maximov, 1945) member of ROCOR Synod of Bishops, left retirement in 1942 to head Croatian Orthodox Church. ‘Brutally murdered’ by Yugoslav Communist partisans 1945; Archbishop Sergei (Stefan Alexeyevich Petrov, 30 Jan 1864-11/24 Jan 1935) of Chernomorsk and Novorossiisk. Emigrated to Yugoslavia 1920, where he joined Synod of Bishops of Church Abroad. His funeral was served by then Archbishop (later Metropolitan) Anastassy (Gribanovsky) of Kishinev, and Archbishop Feofan (Gavrilov) of Kursk in Belgrade. Bishop Makari (Mikhail Mikhailovich Pavlov, 04 Nov 1867-?) of Vladikavkaz and Mozdoksky; later joined renovationist schism. Archbishop Mitrophan (Mitrophan Vasilievich Simashkevich, 23 Nov 1845-1928) of Don & Novocherkassk; known as homilist and spritual writer, works on following subjects: history, archeology, liturgical history, ethnography. Wrote Akathist to Saint Simon, Bishop of Vladimir & Suzdal, Wonderworker of the Kiev Caves.

The main business of the Sobor was to implement a Higher Church Administration in South Russia; this was duly accomplished. Archbishop Mitrophan (Simashkevich) was named President of the newly created Higher Church Administration of South Russia, and Archbishop Dimitri (Abashidze) was Vice President. When Metropolitan Antony (Khrapovitsky) arrived in Stavropol in late 1919, he took over Presidency of the HCA of South Russia due to his seniority.

The Sobor also investigated and settled questions with Committees concerning the Organization of the HCA, parishes, Church discipline, educational matters. Commissions were set up to draw up letters and appeals; on staff and management; and on editorials for periodicals. The Sobor closed on 24 May 1919. It is recognized that while both Higher Church Authorities-that in Siberia, and that in South Russia, in spite of their self-rule, were definitely in canonical submission to Patriarch Tikhon, and in that way they helped to maintain Church unity. The refugees from Siberia largely went to Manchuria and China after the collapse of the Whites; those in South Russia went to Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and other destinations in Europe. Both of these Higher Church Administrations played a large part in both the formation and continuation of the ROCOR, as well as leaving a precedent for the actions to be undertaken by Church bodies in the absence of functioning by their Higher Church Authorities. It is almost as if Patriarch Tikhon’s Ukaz No. 362 was composed with the examples of these two Sobors in mind.

Bishop Mikhail emigrated to Yugoslavia in 1920. He participated in the Council of Karlovtsy of 1921, which was the ‘foundation’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. The Council opened with Divine Services on 08/21 November 1921, and the working sessions began the next day. Bishop Mikhail was the chariman of the committee on the question of parishes. Other committees worked in the following questions: Church Management; Economics; Judicial; Education; Missionary; Military; Spiritual Renewal; and, finally, checking the documents of the delegates. Besides the Hierarchs present at the Council, several unable to travel to Yugoslavia to attend participated by correspondence. Leaving a solid path for the Church Abroad to embark upon, the Council closed on 19 Nov/01 Dec 1921.

After the Council of Karlovtsy, Vladika Mikhail lived at the Monastery Grgeteg, located 15 versts from Sremsky Karlovtsy. He served as a member of the Hierarchical Synod of the Russian Church Abroad. The Monastery is located on the Fruska Gora Mountain in the northern Serbian povince of Vojvodina, and dates from the mid 1500’s. The Church is dedicated to Saint Nicholas. The Monastery was renovated in 1709. It was badly damaged during World War II, and since 1953 it has been gradually undergoing reconstruction. Vladika Mikhail reposed at the Monastery Grgeteg on 09/22 Sep 1925; his funeral was held on 11/24 Sep 1925.

- ortho-rus.ru (the absolute best website for ANY questions concerning the Russian Orthodox Church!)

- (Prikhodskoe dukhoventsva Rossiiskoi Pravoslavnoi Tserkvi i Sverzhenie Monarkhii v 1917 godu)

- russia-ukraine-travel.com

- stavhram.narod.ru

- kds.eparhia.ru

- kavkazweb.net

- sedmitza.ru

- natureweb.ru

- wikipedia commons.

- wikimedia orthodox.net

- spcportal.org

Due to an oversight on my part, credits for most of the photographs with the Biography of Bishop Mikhail (Kosmodamiansky) was omitted. These photographs came from the followingf website: sinodipc.ru

This material is stupendous!

Though I have yet to finish the article, would anyone be offended if I made this comparison which struck me as soon as I got to the shocking part detailing how some of the Russian Orthodox Hierarchy may have cheered on – if not the Bolsheviks – at least the Mensheviks and others who fought for the Revolution against the monarchy.

For the statistic immediately struck me as reminiscent of Rev. 12:4, howe the dragon’s tail [lassooed -!] ‘the third part of the stars of heaven, and cast them to the earth’.

Obviously the dragon would be the red dragon of Communism; and the stars in heaven would be Church’s Hierarchy.

Of course, the rest of the word do not fit this situation; but nonetheless to me it sounds as though this catastrophe of the Russian Revolution and the devil’s ability to lure maybe a third of the Hierarchy into acquiescence was prophesied far in advance.

Though not expert in 20th century Russian history, it strikes me as a significant factor in the success of that atheistic takeover: for had the full quota of Bishops fiercely resisted the downfall of the monarchy PLUS, as St Vladimir of Kiev did, clearly lectured to their people NOT to believe the false propaganda and alluring promises & slogans of the Bolsheviks and their ilk, maybe there could have enough delay to soften or stave off altogether the huge blow that was about to befall Russia, setting it back almost a century in spiritual development and much else.

I do not know that we can pick what we like from the Holy Scriptures, especially from the Apoclaypse of Saint John the Theologian, and then apply what we have picked to historical events, again, of our own choosing, and expect a result of worth. A book entitled `A Second Look at the Second Coming,` by T.L. Frazier, purported to be written from an Orthodox point of view, and published by the Conciliar Press in Ben Lomond, CA, points out that many of the prophetic writings in the Scriptures were written with current events-that is, events from the times they were written-in mind. Furthermore, of course, the great majority of the modern `interpreters` of these prophecies always (and what else can they do?) apply current events of their own times to their interpretation-Mr. Frazier points out that a writer of the 19th century believed the `Kings of the East` mentioned in the Apocalypse were either the Lost Tribes of Israel, or the Turks; while a 20th century interpreter sees the `Kings of the East` as the Red Chinese`! He goes on the state that `the intention of the author of Revelation was therefore to evoke an image of divine chastisement using well-known prophetic language, not to allude cryptically to a twentieth century communist nation.` (or, for that matter, to a 19th century Moslem nation!)

While I am certainly by no means qualified to judge whether or not Mr. Frazier`s book is, indeed, THE epitome of Orthodox interpretation and criticism of the Apocalypse of Saint John the Theologian, it does approach the subject with a sober tone, and totally avoids the sensationalism and wild pronouncements usually surrounding the topic.

At any rate, we must avoid such sensationalism, as well as making ourselves the `center of the universe,` by pointing every word of prophecy to our own times. Seeking out tried and true Orthodox commentaries would certainly be of much greater benefit than attempting to `write our own,` as it were.

Oh yes, I exactly agree that the interpretations are manifold and especially by Protestant fundamentalists, range from a real stretch to inspired by the dark forces! I never pay attention to all these overworked connections.

It`s sort of like how how every century has religious groups claiming that the world will end as soon as the new century arrives, crazy!

Your comment was well taken.

Back to the subject of pre-revolutionary Bishops, I happened to be reading over again the Letters of Archimandrite Gerasim, the hermit of Spruce Island, Alaska. He wrote for example on the Optina Elders day of 1966 – that sad year – the following:

`One archpriest [apparently while visiting St Elias Skete on Mt Athos where Fr Gerasim stayed early in the 20th century] said why the Lord punished our Russia and our people. He said a shocking thing: that twenty of our bishops were atheists… my soul was filled with sorrow… From early childhood I loved the hierarchical church service with the bishop, considering a bishop to be not of this world…`

[Archimandrite Gerasim, would have just loved this series!!!

But he reposed exactly 40 years ago, this coming September 30.]

`Metropolitan Methodius, a conscientious, careful hierarch, believer and lover of monasteries, wrote in one spiritual journal that HALF of our bishops were atheists….` –

So, prophesy or no prophesy, clearly the darkness had seized these hierarchs and pulled them down into disbelief.

While most unpleasant to consider, this information does help explain why so many early 20th century Russian bishops jumped on the revolutionary bandwagon. I would be interested to learn what really happened better than can be understood by such anecdotal pieces of evidence as Fr Gerasim`s.

Of course not only this dedicated hermit in the Alaskan wilderness for 40 years or so, but all the emigres must have been desperately searching to comprehend how such a disaster could have befallen their country.

However, it`s great to see that even those who originally supported the revolution turned out well, as Bishop Mikhail who helped lay the foundation for ROCOR.

The story related here of these early days is rivetiing! Wish a movie could be made to bring it all to life based on these accounts.

Further, I`m surprised the Whites did not have religious activity set up at all.

I wonder why? They were too busy with military operations? I never had realized that.

Akhtirskaya Icon of the Mother of God- Why is the Most HOly Theotokos’ hair uncovered in this icon?